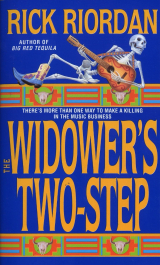

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

53

Mendoza Street ran along the eastern edge of the San Fernando Cemetery. On the lefthand side of the road the graveyard's chainlink fence tilted and bowed at irregular intervals, like a football team had been using it for blocking practice. Evening ground fog had thickened on the cemetery lawn, diluting the tombstones and the air and the trees into one grayish smear.

On the right side of the street was a line of box houses with brightly painted wood slat siding and burglar barred windows and worn tar shingle roofs. The yards were squares of crabgrass, some gravel, some display areas for broken furniture and tires.

There were no kids in sight, nothing of value on the porches, no windows open, few cars parked on the street except those that had been stolen from other parts of town, then stripped and abandoned here. There were plenty of those.

Number 344 was a turquoise onebedroom in slightly better repair than the houses around it. Ralph's maroon Cadillac and a babyblue Camaro were in the driveway.

The front yard was white gravel, decorated with bottle caps. The burglar bars on the screen door and windows were painted white and shaped like ivy, though they were so ornate and thick they reminded me more of a fused curtain of bones.

I rang the bell and stood on the porch for about twenty seconds before Ralph answered the door, midlaugh. Somewhere behind him I could hear Miranda laughing too. The smell of mota smoke wafted out the door.

"Eh, vato." Ralph's glasses shimmered yellow in the porch light.

He stood aside to let me in.

The living room was bare except for one brown couch opposite the window. The interior walls were stark white and the floors hardwood and several bullet holes in the ceiling had been imperfectly spackled over. Driveby souvenirs from the house's previous owner. Ralph had gotten the place cheap because of that.

Through an archway I could see Miranda sitting at a dining table across from another woman. They were both laughing so hard they were wiping away tears. Miranda was still dressed as she had been this morning– in jeans, boots, and my Tshirt. Her face had more colour, though; her posture was a little less weigheddown. The other woman was a young Latina with long coppery hair and a bright yellow dress that showed lots of leg. She wore black pumps and silver earrings and makeup.

When the women saw me they both smiled.

Miranda said my name like it was a pleasant memory from twenty years ago.

The other woman got up and came to give me a hug. "Hey, vaquero."

She kissed both my ears, then stepped back to appraise me.

"Cally," I said. "How you doing?"

"Asi asi." Then, still in Spanish, "You've got a nice lady here."

I looked at Miranda, who was still smiling and wiping her eyes. There was only one lit joint in the room—in Ralph's hand—but there were assorted munchies on the table—bags of tortilla chips, a steaming canister of Ralph's homemade venison tamales, a plate of Ralph's special pan dulce—the kind with the green flecks in the icing. Uhoh.

Ralph saw my expression and spread his hands. "Everything's cool, vato. Just relaxing, doing the grief process, right?"

I stared at him.

Ralph shrugged, turned to Cally. "Eh, mamasita, let's go out back, get Chico to take you home."

Cally said goodbye to Miranda, gave her a hug, then kissed me one last time. Ralph gave us an amused grin, then led his lady friend out the screen door.

In the floodlit backyard, Chico of the yellow pirate bandanna and the easily kicked balls was working on a halfassembled Shelby. Ralph kept the car out there just for his grunts—sort of like the block table for kids at the doctor's office. Chico stopped messing with the fuel pump and quickly wiped his hands when Cally and Ralph came out.

I sat across the table from Miranda and turned the plate of laced pan dulce around.

"How many?"

Miranda blinked very slowly. "Two? I don't remember."

"Great."

My face was apparently good enough to warrant another laugh. She held her hand over her mouth, quivered silently for five beats, and then did a little snort on beat six.

"I guess I shouldn't ask how you're feeling," I ventured.

"I'm sorry," she said. "I just—it feels good to laugh, Tres. Cally's so nice. Ralph is really lucky."

"Sure," I said.

"Have they been together long?"

I hesitated. "Actually they're more like business partners."

Miranda frowned. She reached for another pan dulce before I moved the plate.

"Better not," I said.

"Oh—right." She went for the bag of Doritos instead, examined the plastic edges.

"Ralph and Cally told me not to be mad at you. They talk about you pretty highly– said you usually knew what you were talking about, even if it wasn't fun to hear."

Outside, Ralph had finished giving Chico his orders. Ralph tossed him a set of car keys, then swatted Cally's behind by way of farewell. She grinned, then followed her yellow bandannaed chauffeur around the side of the house, out of sight.

"I spoke to Allison today," I said.

Miranda smiled ruefully. "My best friend in the whole world."

I told her about Allison moving out, about the addresses we had tracked, about how I had some new information on Brent's murder.

Miranda tried to pull her expression together, to anchor herself on my words. Her attention disintegrated quickly.

There was a small hole in the upper corner of the Dorito bag, much too little to get a chip through. The problem was too much for Miranda's stoned sensibilities. Finally she started breaking up chips inside the bag with one finger, getting them small enough to fit through the hole.

My story faltered to a stop.

Miranda looked up, probably wondering why the sound of my voice had gone away.

"What?"

"Milo wanted to see you tonight, to talk strategy. Maybe I should call him, tell him tomorrow would be better."

She processed those words.

"Milo wants—" Her voice trailed off, like she was just remembering that name. "My brother is dead and Allison's leaving town and Milo wants to talk about Century Records.'"

A car engine started in the driveway. Seconds later the headlights of the babyblue Camaro slipped through the livingroom window, over the couch and across the livingroom table, then disappeared down Mendoza Street.

Miranda moved a small piece of tortilla chip across the table with her finger, like it was a checker. "We should talk, Tres. Before we see Milo."

"I know."

"The things you said last night, the way you made me out. . ."

The screen door screaked open and Ralph came in alone.

I turned back toward Miranda. "Like I said, tomorrow would be better. I'll call Milo."

"Pinche Chavez," Ralph put in. "This lady need help it ain't going to come from his sorry ass."

He looked at Miranda. She rewarded him with a faint smile.

I walked to the phone. Ralph sat where I had been sitting and helped himself to the tamales. As he pried off the canister lid a cloud of steam and cumin and spiced meat smells mushroomed up. He pulled out three of the tamales and began unshucking them. He told Miranda not to worry about a thing. We'd be taking care of her.

Gladys answered the phone at the agency office.

"Milo in?" I asked her.

Gladys sounded like she was shuffling furniture, or maybe moving quickly into another part of the office.

Her tone was low and urgent.

"He's out," she whispered. "You mean you don't know—"

"What do you mean, out?"

Our questions crossfired and tangled. We both backtracked and waited.

"Okay," I said. "Tell me what happened."

Gladys told me how Milo had cancelled his dinner meeting with an important client, then stormed out of the office. He'd thrown his pager on Gladys' desk on the way out, telling her "Don't bother." He'd said he had some business to take care of. Gladys had been worried enough to check Milo's desk, which she'd been forbidden to do but which she apparently knew well enough to notice what was missing—the handgun Milo kept in the middle drawer. She had just assumed, me being the most disreputable person Milo knew, no offense of course, that he'd gone somewhere with me. Gladys was about to tell me something else, something to justify her prying, but I cut her off.

"How long ago?"

"Ten minutes?" she said, plaintive, apologetic.

I hung up and looked at Ralph, then at Miranda.

"What?" Miranda said.

"Milo just left the office with a gun," I said.

My words took a while to impact, and even when they did the effect was dull. Miranda's brown eyes slid down to my chin, then my chest, then to her own hands. She pushed the Doritos away. "You know where he's going?"

"Yes."

"He's trying something dangerous. For me."

"Yes."

Ralph ate, looking back and forth between us. His expression had all the depth of someone watching a barroom TV program. When he finished his tamale he wiped his hands and then spread them, a hereIam gesture.

"Maybe so," I agreed.

Ralph slowly broke into a grin, like I'd given him an answer he'd been expecting for days.

I looked at Miranda. "You could stay here. Ralph is right—he and I could take care of it for you."

Miranda flushed. Anger seemed to be burning the marijuana slowness out of her eyes.

"I'm coming. Just tell me where we're going."

Ralph straightened up in his chair so he could take out Mr. Subtle, his .357 Magnum.

He clunked it on the table and said, "Dessert."

54

The night sky was bright with thunderclouds and the air smelled like metal. The raindrops were infrequent, warm and large as birds' eggs.

Ralph pulled the maroon Cadillac in behind the VW on the north side of Nacogdoches, about half a block down from the entrance of the storage facility.

He met us by the chainlink fence of the sulfur processing plant. The wind was whipping around, pushing Miranda's hair into her mouth. Her white Berkeley Tshirt was freckled with rain.

"Bad," I told Ralph.

Across the street the gates of the floodlit facility were open crookedly. Sheck's huge black pickup truck was just outside. The security booth was empty; Milo's green Jeep Cherokee was parked at a fortyfivedegree angle across the entrance, its fender crunched against the booth's doorway and its driver's side door open. If the guard had been in the booth, he would've had to crawl over Milo's hood to get out. From this angle I couldn't see the yard between the two buildings.

Monday night. Traffic along Nacogdoches was light. What cars there were turned into the industrial parkway before getting to our block. Two blocks down, five or six teenagers were waiting at the VIA bus stop.

Ralph looked at the yard. "No cover worth shit. Chavez, man—stupid ass isn't worth saving."

"You can back out," I said. "No obligation."

Ralph grinned. "?Mande? "

I nodded my thanks, then looked at Miranda. She was hugging her elbows. Her brows were knit together. On the ride north she had managed to shake off most of the effects of the laced pan dulce, but she still had a withdrawn, slightly puffedup demeanour, like a very cold parakeet on a perch. She shifted her weight onto one leg and lifted the other boot behind her knee. "What can I do?"

I think it was meant to sound brave, gung ho. It came out plaintive.

I got out my wallet and gave Miranda one of Detective Gene Schaeffer's cards, which I'd had the unhappy fortune to collect on many occasions.

"You can stay here if you want," I told her. "Be our anchor. Ralph has a cell phone. You hear any trouble, any shots, call that number and ask for homicide, Gene Schaeffer.

Insist on talking to him. Tell him where we are and what's happening and tell him to get on the phone with Samuel Barrera and get down here. We're giving them probable cause to enter. Do you have all that?"

Miranda nodded uncertainly.

Ralph looked at me, produced his fallback gun, a Dan Wesson .38, and held it toward me. "I know what you're gonna say, vato. But I got to offer."

"No thanks."

"I'll take it," Miranda said.

She did, gingerly. She held the gun correctly, pointed it down, unlatched the barrel and rolled it, checking the cylinders. She closed it and looked at me defiantly. "I'm not being an anchor." Then to Ralph, "Take your own damn cell phone."

Ralph laughed. "This lady's all right, man. Vamos."

He got out Mr. Subtle. We crossed Nacogdoches and walked toward the gates, staying close to the fence.

By the time we got there rain was coming down heavy enough to make a highpitched pinging against the corrugated metal roofs of the storage buildings. In the yard were the same two freight boxes that were there that afternoon, but this time they were attached to semirigs with the motors running. One loadingbay door was open. No one was on the dock, but looking underneath the first truck we could see long shadows from two pairs of legs on the other side—men talking between the trucks. One of them wore jeans and boots. The other had slacks, dress shoes.

I turned to Miranda. "Last chance."

But it was already happening too fast. Ralph knew when to take advantage, and he knew there wouldn't be a better chance to close some distance. He went right, walking quickly toward the cab of the truck. I moved left to the side of the building and began jogging toward the first loading dock. Miranda followed me.

The gunshots came when we were almost to the dock. I was running forward before I fully registered what I had heard. Two shots, both incredibly loud, from inside the warehouse, followed quickly by two shots from the right, behind the first truck. Those had been almost as loud—the report of a .357. Ralph had taken advantage of timing again.

We met Ralph under the loading dock, where metal slats had been laid across from the cement to the truck bed. The dock was only about five feet high. We had to crouch to avoid being seen from inside. Ralph had his gun out and was shaking his head, whispering Spanish curses and looking mildly displeased. Behind him were some lowpitched groans, almost muffled in the rain and the truck engines.

" Cabrons tried to get smart. One of them might live, I think."

I looked under the truck. On the opposite side, thirty yards away, the man in the slacks and the Tshirt who had been with Jean Kraus in the BMW earlier in the day was curled up on the asphalt, a pistol about ten feet away from him—kicked there by Ralph, probably. The man was making the groans as he tried to stop the bleeding in his thigh.

He was kicking himself along the pavement with his good leg, like he was trying to get somewhere, but he was only succeeding in making small circles. His fingers clutched his leg where the blood was seeping through, soaking his pants and smearing the pavement. He had gone at least one complete circle in his own pool because the blood was on his face and in his hair too. In the outdoor lights the sticky places glistened purple.

Redhaired Elgin Garwood was ten feet closer to us. He was very dead. A .357 round had eaten a fistsized chunk out of his chest, just to the left of his sternum. He was staring at the sky and rain was running off his forehead. His 9mm was still in his right hand.

My ears roared. I tried to think but the engines and the rain and the afterecho of gunfire made it impossible. Inside the warehouse, an argument was going on. More groaning. Was it possible they hadn't recognized the gunfire outside as a separate problem? Maybe the echo inside the building . . .

A carload of high school kids drove by on Nacogdoches, oblivious, grins on their faces, heavy metal music blaring.

I held my breath, then popped my head up for a brief look into the warehouse.

A twosecond snapshot—Tilden Sheckly and Jean Kraus arguing. Sheckly with a gun stuck in the waist of his pants. Kraus' Beretta in his hand. The apparent subject of the argument, a mountain of wounded human being on the floor in front of them. Milo Chavez, the soles of his very expensive shoes pointed toward me, one hand clutching at his shoulder, maybe his heart. A single line of blood ran away from his body, stopping after two feet to seep into and around a legalsized document that Milo had apparently dropped, then continuing.

I ducked back down and pressed my back against the cement wall of the loading dock.

I closed my eyes and tried to memorize the placement of things.

When I opened my eyes again I was looking at Miranda. Her face was pale, her hand pressed lightly over her mouth. She was staring under the truck, watching the man kick a circular path through his own blood, watching the other one with the hole in his chest, the one who had brought his wife Karen to Willis' parties.

She started shaking.

"Get the hell out, Ralph." I grabbed the cell phone from him, then, with much greater hesitation, traded it with Miranda for the .38 Wesson. "You just killed a cop. An Avalon County deputy, but still a cop. Miranda goes too—Miranda makes the call to Schaeffec, neither of you were ever here."

Ralph's face hardened. The lenses of his glasses gleamed solid yellow. He rubbed his thumb along the safety catch of the .357. "That's too bad, vato."

"No," I said.

But I couldn't stop it. Ralph crouched just low enough for the shot. The muzzle blast flared, illuminating the underside of the truck. The man who had been kicking a circle in his own blood stopped kicking. A new red pattern, less circular, began seeping into the asphalt around his head.

I counted three very long seconds. Miranda crouched next to us, stone still. Her face had the dazed, unhappily sated look of someone who was just realizing that she'd overdone it at the banquet table.

Ralph turned to me, gave a very small, cold smile. "Ain't standing in no lineup for Milo Chavez, vato. Lo siento."

Then he was gone, Miranda whisked into his wake and pulled along willingly or no, and I didn't have the luxury of thinking.

There had been a third shot. Jean Kraus would be coming out.

It had been almost twenty years since I fired a gun. I moved five feet to the left and turned, lifted above the lip of the loading dock just enough to see and fired a round toward the roof, roughly in the direction Sheck and Kraus had been standing. Sheck was still there, but now partially crouched behind a large wooden crate. Kraus was twenty feet closer to the entrance. When I fired he almost fell over himself backtracking. I didn't have time to notice if Milo was still breathing.

I ducked and moved toward the side steps of the loading dock.

I yelled, "Sheckly! Two men are down out here. The police have been called. We've got about three minutes to work this thing out."

Miranda and Ralph had disappeared through the gates. There were no sirens. Yet.

A huge drop of rain caught me on the nose, forcing me to blink. Inside it was silent until Sheckly let out a strained noise, a poor imitation of a laugh. "You just don't give up, son, do you? You think I'm gonna stop to sign ole Milo's papers right now I'm sorry—I'm a little busy."

I was at the top of the steps now, my body flat against the wall just outside the entrance.

"You wanted Chavez shot?" I called. "Was that your idea? If I was you, Sheck, I'd put some distance between myself and Kraus right now."

I crouched, looked in, and nearly got my head shot off anyway. Kraus had targeted effectively. I fired back stupidly, ineffectually into the air and ducked around the corner again. My hand was already numb from the recoil. The smell of primer was in my nose.

God, I hate guns.

In my third snapshot look I had noticed a few new things. There were rows and rows of large cylinders stacked upright just behind Kraus. Each was about seven inches in diameter and five or six feet high, wrapped in brown paper and capped on either end with plastic, like huge canisters for architects' drawings.

The other thing I noticed was Sheckly. He had been standing again, making no attempt to find cover. And he wasn't staring at the entrance, looking for me. He was staring at Milo Chavez's chest. Chavez's hand had fallen away from the shoulder and was now limp at his side. That was not good.

Jean Kraus called out, "There is nothing we can't discuss, Mr. Navarre." His voice was collected, genial, a little too loud to be trusted. "Your friend needs a doctor's attention, I think. Perhaps we should call a truce."

"Go on, Navarre," Sheckly called. "Get out of here."

"Let's discuss it," I called. "Like Kraus says. Did he tell you about the thirteenyearold French boy he killed? Kraus discussed his way out of that one real well. I imagine he'll do the same here—get safely to another country and leave you with the wreckage and the bodies, Tilden. How does that sound?"

Kraus' voice came back a little bit louder and a little less genial. He made sure I heard the action on the Beretta as he chambered the next round.

"I have my gun pointed at your friend's head, Mr. Navarre. At present he can still be saved. Throw your gun into the doorway and come into the warehouse and perhaps I will reconsider my options. Do you understand?"

Sheckly said something very insistent in German, an order. Kraus responded derisively in the same language.

Sheck barked the same command again and Kraus laughed. Somewhere very far away there were sirens. The rain kept falling in my face, soaking through my shirt.

"No good, Sheck," I yelled. "Give it up and I'll make sure they listen to you. Let Kraus and his associates be the ones they lynch. Otherwise we're talking multiple murders and Huntsville and a bunch of guys in Luxembourg laughing their ass off about you.

What's it going to be?"

"One—" Kraus started to count.

Milo Chavez managed a noise, a low mumble that might've been a scream if not for weakness and shock.

Sheck barked something else in German and Kraus yelled "Two—" and I gave up hope and came barrelling into the doorway to fire when guns went off.

Not mine.