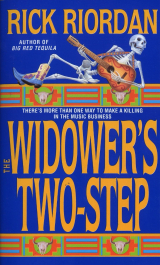

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

44

By the time I picked up Miranda at Silo Studios, another promised cold front had edged its way south and stalled, pressing humid air and gray clouds over Austin like a sweaty electric blanket.

The folks seventy miles north in Waco were probably cool and comfortable. Then again, they were in Waco.

Milo Chavez was too busy to speak to me. He and one of the engineers were glued to the sound board, listening in awe to the new vocal tracks Miranda had laid down over the last two mornings.

"Fifteen takes," Milo mumbled to me. "Fifteen goddamn takes of 'Billy's Senorita' and she blew it away in one try this morning. My God, Navarre, losing that first demo tape was the best thing that ever happened to us."

He laid his hand on the little BOSE speaker like he was consecrating it.

Chavez agreed to let me take Miranda back to S.A. early as long as I got her to her appearance tonight on time. Miranda said she was starving. She suggested lunch on the way back to town. I had a conscience attack and called my brother Garrett to see if he could join us. Unfortunately he could.

When we got to the Texicali Grille we found Garrett at an outside table. He'd pulled his wheelchair under one of the metal umbrellas and Dickhead the parrot was waddling stiffly back and forth on his shoulder. Danny Young, the owner of the Texicali, was sitting backward in the chair across the table.

Danny was a family friend, connected to the Navarres through a network of South Texas kin and nearkin that I never could quite remember.

Many years back Danny had moved his restaurant business from Kingsville to Austin and decided to grant himself an honorary double degree in alternative politics and burgerflipping. He announced that the half of Austin below the Colorado River must secede from the growing yuppiness of the north, so he hoisted a green XXXL Tshirt up the flagpole at the Texicali and started calling himself the Mayor of South Austin. I think Danny's political platform said something about flip flops and salsa and Mexican beer. I'd told him he could annex San Antonio anytime he wanted.

Danny's hands took up most of the top of the chair back. His greying brown hair was pulled into a ponytail and when Garrett said something about Samsung Electronics moving to Austin, Danny laughed, flashing the silver in his teeth.

"Hey, little bro." Garrett waved at me. Then he saw Miranda and said, "Damn."

She was dressed seven hours early for her fifteen minute spot at Robert Earle Keen's Halloween Night Show. She'd chosen a cotton blouse made of big orange and white squares, a black skirt, tan boots, lots of silver jewellery. Her hair and makeup were airbrush perfect. Most of the time I would've called the look too much, too Big Hair Texas for my tastes. This afternoon, on Miranda, it worked for me.

I shook hands with Garrett and Danny.

I started to introduce Miranda but Danny said, "Oh, hell, we've jammed together."

Miranda laughed and gave Danny a hug and asked him how his washboard playing was coming along. Danny told Miranda she'd sounded just fine on Sixth Street last month.

Garrett kept looking at Miranda. He wasn't having much luck getting his mouth closed.

The parrot eyed me cautiously, like he was forming a vague memory of unhappier times, before Jimmy Buffett and ganja.

"Noisy bastard," he decided.

Danny gave Miranda one more hug, then asked us all what we were having. Garrett told him just about everything, especially Shiner Bock. My stomach went into a little gallop, reminding me about the large quantity of whiskey I'd subjected it to for lunch.

"Make mine iced tea," I corrected.

Danny looked at me funny, like maybe he didn't know me after all, but he went inside to place the order.

"The renowned Miss Daniels," I introduced. "My brother Garrett."

Miranda said, "Pleased to meet you."

Garrett shook her hand, looking at me while he did it.

He asked me some silent questions. I just raised my eyebrows.

Garrett gave Miranda one of those toothy grins that makes me wonder if he goes to the orthodontist to get his teeth unstraightened and sharpened on purpose. "Love your tunes."

Miranda smiled. "Much obliged."

"I thought you only liked them," I reminded Garrett. "I thought she wasn't Jimmy Buffett."

Garrett told me to shut up. So did the parrot.

Miranda laughed.

"Here, asshole." Garrett fished something out of the wheelchair's side pocket and handed it to me. It was about the size of a computer disk, wrapped in brown paper and sealed with a black and white peace sign sticker.

When I started to protest, he held up his hands in defence. "Did I say anything? Take the damn disk—it's nothing. Some security programs I thought you could use. Don't even consider it a present."

Miranda looked back and forth between us, a little confused.

"Nothing," I promised her.

"Absolutely nothing," Garrett agreed. "Everybody turns thirty. Forget it."

It was Miranda's turn to open her mouth. She looked at me indignantly.

"I'm hoping somebody will gift me a noose," I said. "For my brother."

"You didn't—" Miranda started to say something else, then realized she didn't know quite what.

Garrett was still grinning. "He's embarrassed. Getting old. Not having a day job yet."

"Or maybe hanging is too quick," I speculated.

"Dickhead," squawked the parrot.

Miranda looked back and forth, at a loss for words. It's a look I've seen a lot from women who find themselves between two Navarre men.

"End of subject," I announced. "Tell Miranda how you're reconfiguring your computer to take over the world."

Without too much more encouragement Garrett started telling us about the bastards running RNI, then about his latest unofficial projects. After a while Miranda stopped staring at me. The conversation swung around to Jimmy Buffett, of course, which segued into Miranda's pending fameandfortune deal with Century Records. Garrett tried to convince Miranda that she could do a bangup cover of Buffett's "Brahma Fear"

on her first album. After the second round of Shiner Bocks, Miranda and Garrett had just about worked out the arrangement.

During the conversation I sipped my iced tea and subtly moved Garrett's gift off the table, then into my backpack. Out of sight, etc.

When the food came Danny sat with us for a while. We ate Texicali burgers heavy with salsa and Monterey Jack and watched the afternoon traffic speed down South Oltorf.

Dickhead the parrot sat on Garrett's shoulder, holding a tortilla chip in his claw and eating it piece by piece. He hadn't yet learned to dip it in salsa. That would probably take another month.

After a while Garrett said he had to get back to work and Danny said he had to get back to the kitchen. A few raindrops started splattering the patio.

"Nice meeting you," Miranda told Garrett.

Garrett wheeled his chair sideways and the parrot shot its wings out, correcting its balance. "Yeah. And hey, little bro—"

"Say it and die," I warned.

Garrett grinned. "Nice meeting you, too, Miranda."

When we were alone I started shredding the wax paper from the burger basket.

Miranda put her boot lightly on top of mine.

Yes, I was wearing the new boots. Just happened to be in front of the closet.

"Hard to like them sometimes," Miranda said.

"What?"

"Older brothers. I wish I'd known—" She stopped herself, probably remembering my injunction to Garrett. "Here you drove all the way to Austin to pick me up, spent half your day."

"I wanted to."

She took my hand and squeezed it. "The taping went really well today. I owe that to you."

"I don't see how."

She kept a hold on my hand. Her eyes were bright. "I missed you last night, Mr.

Navarre. You know how long it's been since I missed somebody that much? Can't help but change my singing."

I stared out at the traffic on Oltorf. "Has Les contacted you, Miranda?"

Her grip on my hand loosened just slightly. She had trouble maintaining her smile.

"Why would you think that?"

"He hasn't then?"

"Of course not."

"If you had to get away for a few days," I said, "if you had to go somewhere safe that not too many people knew about, could you do it?"

She started to laugh, to put the idea away, but something in my expression made her stop. "I don't know. There's the show tonight, then tomorrow is free, but then the tape audition on Friday—you don't seriously think—"

"I don't know," I said. "Probably it's nothing. But let's say you had to choose between keeping your schedule and being sure you stayed safe."

"Then I'd keep my schedule and take you along."

I looked down at the table.

I turned over the bill and discovered that Danny Young had comped the meal. He'd written "Nothing" in black marker across the green paper. The Zen waiter.

Miranda turned my palm up so hers was on top.

Raindrops starting pingpinging more steadily, a slow threequarter time against the metal umbrella.

"Anyplace else you need to go in Austin?" she asked. "As long as I got you up here?"

I watched the rain.

I thought about Kelly Arguello, who would probably have some more paperwork for me. She might be sitting on her porch swing in Clarksville right now, clacking away on her portable computer and watching the raindrops pelt the neighbour’s yard appliances.

"Nothing that can't wait," I decided.

45

Two hours later we were back in San Antonio, in Erainya's neighbourhood. I had promised Jem I'd come by Halloween evening, but it only took Jem a couple of blocks worth of trickortreating to decide that Miranda was the one he really wanted to play with.

She raced him up each sidewalk. She laughed at his knockknock jokes. She showed the most appreciation for his costume. Jem was tickled to death when Miranda offered to be his Miss Muffett.

"She's good with kids," Erainya told me.

Erainya and I were sitting on the hood of Erainya's Lincoln Continental, watching the action.

There was plenty of it in Terrell Hills that evening. The neighbourhood Anglo kids were travelling in twos or threes, dressed in their storebought princess and ninja outfits, their pumpkin flashlights switched on and their plastic jacko'lanterns stuffed with candy. The bubba esque parents strolled a few feet behind, drinking their Lone Stars, talking on the porches, some of the dads with little portable TVs to keep track of the college football games.

Then there were the kids imported from the South Side travelling in groups of ten or twenty, unloaded from their parents' old station wagons into the rich gente neighbourhoods to gather up what food they could. They dressed in old sheets and maybe some smeared face paint, sometimes a plastic dimestore mask. The bigger kids, fifteen or sixteen years old, did their best to cover their hairy arms and their faces.

They let their younger siblings do the asking. The parents always stayed well back on the sidewalk, and always said thank you. No Lone Stars. No portable TVs.

Then there were the oddball loners like Jem. He was skipping awkwardly along in his bulbous homemade spider costume, the black fur coming off on the boxwood hedges and the wire arms flailing and catching on the paper skeletons people had hung from their mesquite trees. By the third block he didn't have much costume left, but nobody seemed to mind. Especially not Jem.

I watched Miranda chasing Jem back down another sidewalk. Both of them jumped over a mesquite that grew flat across the front yard in the shape of a wave.

Jem showed off the pralines and watermelon slice candy he'd scored, then kept running with Miranda close behind.

"Way to go, Bubba," I told him.

Miranda flashed me a smile. She went after Jem like she'd been doing it all her life. Or all of Jem's, anyway.

Erainya muttered something in Greek.

"What?" I asked.

"I said you look like a Turk, honey. Why so sour?"

She was wearing the standard black Tshirt dress. When I'd asked her why no costume she'd said, "What, I need to look like a witch, too?" Her arms were crossed and she was grabbing her sharp elbows. Her expression was a little softer than usual, but I suspected that was just because she was tired.

Over Erainya's objections, Jem had told me about their flush job at six that morning.

He loves the canI useyourphonesoIcanlocatethisboy'sparents routine.

According to Jem the skipped husband's girlfriend opened the door right away and even offered them a Coke. Erainya had collected an easy day's fee from the wife's lawyer.

"I'm not sour," I protested.

Erainya tightened up her body a little more, extended one finger toward me like she was going to jab me with it. "You got a nice lady with you, next week you get to come back to work with me—what's the trouble?"

"It's nothing."

Erainya nodded, but not like she believed me. "You had it out with Barrera?"

I nodded.

"He give you reasons why people might be dying over this business with Sheckly?"

"Yes. And reasons why it was over my head."

We watched Jem wiggle his spider arms for the guy at the next front porch. The guy laughed and gave Jem an extra handful of candy from the large wicker basket he was holding. The guy also watched Miranda appreciatively from behind as she walked down the sidewalk. I wondered how much force it would take to fit the wicker basket onto his head.

"Don't listen to him," Erainya said. "Don't let him cut you down."

I looked at her, not sure if I'd heard correctly.

She examined her talon fingernails critically. "I'm not saying you did good, honey, getting involved the way you did. I'm not saying I like your procedures. But I'll say this just once—you should do P.I. work."

It was hard to read her expression in the dark.

"Erainya? That you?"

She frowned defensively. "What? All I'm saying is don't let Barrera treat you second class, honey. Cops make the worst P.I.s, no matter what he tells you. Cops know how to react, how to be tough. That's it. Most of them don't know the first thing about opening people up.

They don't know about listening and untangling problems. They don't have the ganis or the sensitivity for that kind of work. You got ganis"

"Thanks. I think."

Erainya kept frowning. Her eyes drifted over to Miranda, who was racing Jem down the steps of the last porch on the block. "How bad is the girl mixed up with this case?"

"I wish I knew."

"Is somebody going to get hurt here?"

"Not if I can help it."

Erainya hugged her elbows and, just once, kicked the tire of the Lincoln with her heel, hard. "You could do worse, honey."

Jem and Miranda came back at full tilt, Jem running past me and Miranda running right into me, grabbing my forearms to stop herself.

She had a little praline crumble at the corner of her mouth. Sneaking some of the loot.

"Hey," she said.

Jem said he was ready to drive to another neighbourhood now.

A Latino family of twelve walked by, the parents saying pretty much the same thing in Spanish. The father looked emptyeyed, like he'd been driving around since way before sunset. The kids looked tired, the mother a combination of hungry and uneasy, doing her best to skirt her kids around the Bubba fathers with the portable TVs and the little blond kids with costumes that cost more than all her family's shoes put together.

Erainya frowned down into Jem's candy bag, carefully chose a Sweetarts, the sourest thing she could find, and looked back up at me reprovingly.

Then she ruffled Jem's balding furry headpiece and told him to get in the car.

46

"We ain't going to make it."

Miranda didn't sound concerned, exactly. More like she was getting a taste for tardiness and wasn't quite sure if she liked it or not. She'd never been late to a gig before. Somebody else had always driven. Somebody responsible. No side trips to trickor treat with fouryearolds.

"I thought this was supposed to be impromptu," I said. "Drop in on Robert Earle. Sing a couple of songs. Casual."

"This took Milo about a month to arrange, Tres. Century's got A & R folks coming from Nashville and everything. Milo will not be thrilled."

She tried to fix her makeup again, not an easy task in a moving VW at night, even with the top up. She'd wait until we passed under a highway light, then check her lips in the two seconds her face was illuminated in the visor mirror. She looked fine.

During the next lighted moment I checked my watch.

Nine o'clock exactly. At Floore Country Store, two miles farther up the road, Robert Earle Keen would just be starting his first set, expecting to be pleasantly surprised halfway through by his old buddy, Miranda Daniels. Milo would be pacing by the entrance. Probably with brass knuckles.

We zipped along with the front trunk rattling and the left rear wheel wobbling on its bad disc. I patted the VW's dashboard.

"Not this trip. Break down on the way home, please."

Of course I told the VW that every trip. VWs are gullible that way.

Miranda put away her makeup. She stared out at the ragged black line of huisache trees blurring past. "I like your brother Garrett. I like Jem and Erainya."

"Yeah. They grow on you."

She circled her hands around her knees.

"Thirty," she speculated.

"Hey—" I warned.

She smiled. "Is Garrett right?"

"Hardly ever."

"I mean about the way you feel—that you think you should've settled into a steadier job by now?"

The flashing yellow light that indicated the turnoff for John T. Floore's popped over the hill on the horizon.

"Don't let Garrett fool you," I told her. "Behind the tiedye and the marijuana, he's the most Catholic person left in my family. He believes in moral guilt."

Miranda nodded. "I imagine that's a yes."

We turned left across traffic.

The Floore Country Store sat with its back to the highway, its face to Old Bandera Road and miles and miles of ranchland. A million years ago when John T. Floore opened the place it really had been a country store—the only option for a meal or groceries or a beer this side of an Edsel ride into San Antonio.

The "store" side of the business had long ago become a sideline to the bar and the country music, but a sign above the exit still read: Don't forget your bread.

Tonight the lights of Floore's back acre were blazing. Pickup trucks lined both sides of Old Bandera Road. The limegreen cinderblock front of the bar was even more thoroughly covered with plywood signs than it had been on my last visit. Some advertised beer, some bands, some politics. WILLIE NELSON EVERY SATURDAY

NIGHT, one of them said.

We drove past, looking for a parking space. From the road, Robert Earle Keen's music sounded like random booming and throbbing, a tape played backward very loud.

There was a crowd of cowboyhatted folks at the door.

I doubled back, drove past the farm equipment repair shop, and parked on the opposite side of the bridge that went over Helotes Creek.

Milo had apparently been watching for my car, because by the time we got Miranda's guitar out of the trunk and started walking across the bridge he was already in the middle coming toward us, scowling like the troll from the Billy Goats Gruff.

"Come on," he told Miranda, taking her guitar from me without meeting my eyes.

"Sorry," Miranda tried.

But Milo had already turned and started back toward the bar.

Miranda cleared a path for us pretty neatly. The old man at the door tipped his hat to her. Several people in line backed up to let her through, then had to back up even more for Milo. A greasylooking Bexar County deputy with a greying Elvis haircut told her howdy, then escorted us across the bar room and out the back door.

The twenty or thirty picnic tables in the gravel lot were all jammed. So was the cement dance area. At one of the tables by the back of the building, Tilden Sheckly sat with several of his cowboy buddies. I caught his eye and his standard easy grin as we walked past.

The only illumination on the dance floor was from outdoor bulbs on telephone poles, coloured Christmas lights, and neon beer signs along the fence. Up on the green plywood stage, Robert Earle was singing about bass fishing. He'd gotten a beard and a classier outfit and a bigger band since the last time I'd seen him play.

Miranda turned to Milo. "Where—"

Milo nodded over to another picnic bench by the chainlink fence, about fifty feet from Sheckly, where a few young guys in slacks and white dress shirts were sitting. Not locals. One of them was even drinking a wine cooler. Definitely not locals.

"Just be yourself," Milo advised. "Do the numbers we talked about. Robert Earle's going to start you with a duet on 'Love's a Word.' Okay?"

Miranda nodded, glanced at me, then at the A 8c R men across the yard. She tried for a smile.

Milo handed her over to the deputy with the Elvis haircut. He walked her up to the stage. Robert Earle had just finished his bassfishing song and was announcing over the applause that he'd just found out one of his oldest friends in the whole world was in the audience. He said he surely wanted to invite her up to do a little music.

A spattering of applause started up again, getting a little more enthusiastic when people saw Miranda coming up the steps. Apparently the crowd recognized her.

Milo waited long enough to make sure she'd gotten onstage safely and that her mike was working. Robert Earle started kidding with her about the last time they'd played together—something about eating mescal worms and forgetting the words to "Ashes of Love." Miranda kidded him back. If she was nervous she hid it well.

Milo shot me a quick, disapproving look. He walked past me, toward the table where the important people sat.

I stared at his back for a few seconds, then decided I might as well go inside and buy myself a birthday beer.

The interior bar was a walnut box that amazingly managed to hold the elbows of the bartender and six or seven customers without falling apart. Nobody was in costume, unless you count kicker clothes. Nobody had pumpkins or candy. Beers were displayed in a glass refrigerator case along with thick black wrinkly curlicues that according to one sign were dried sausage. $3.50 per ring.

I bought a can of Budweiser and no dried sausage. I walked outside again. I crunched over the gravel toward Sheckly's picnic table.

Onstage Robert Earle was plucking out an acoustic intro. Miranda was starting to sway. Without a guitar, her hands were loose at her sides, her fingers tapping lightly on the folds of her skirt.

When Sheckly noticed me coming he mumbled something to his lackeys and a round of laughter started up. The skin of Sheckly's left cheek, where Allison had landed the horseshoe, was corpse yellow, stained with Mercurochrome. The cut itself was covered with a line of beige squares that looked like strapping tape.

The man sitting next to him was almost as ugly, even without flesh wounds. He had pale skin, orange hair, a thick unintelligent face. Elgin Garwood.

"Hey, son," Sheck said. "Good to see you."

I slid onto the opposite bench, next to one of the cowboys.

"Surprised to see you here," I told Sheck. "Not minding the shop tonight?"

He spread his hands. "Sunday's my day to get out. I like to see the other clubs, keep tabs on who's playing."

I gestured toward the table of stonyfaced A 8c R men. Milo was sitting with them now, trying to look self assured, smiling and gesturing proudly toward the stage.

"Especially when reps from the record company come looking at Miranda," I told Sheck. "Keeps Milo on his toes, wondering if you'll come over and ruin the night."

Sheck grinned. "Hadn't thought of that."

Elgin was glaring at me.

I gave him a smile. "They let you off surveillance tonight, Garwood, or did Frank just get tired of your clown act?"

Elgin rose real slowly, keeping his eyes on me. "Get up, you son of a bitch."

The other cowboys glanced at Sheck, looking for a cue. Over by the fence, one of the Bexar County deputies on security was frowning in our direction.

"Go on, Elgin," Sheck said lazily. "Go inside. Get yourself another beer."

"Let me call Jean," Elgin said.

Sheck's smile stayed in place but his eyes dimmed a little. The fire sank a little farther back in his skull.

"Probably a good idea," I agreed. "At least your Luxembourg friends are professionals."

Elgin made like he was going to come across the table at me, but Sheckly raised his fingers just enough to get back his attention.

"Go on," Sheckly told him. "Don't call anybody. Go inside and get yourself a beer."

Elgin looked at me again, weighing the pros and cons.

"Go on," repeated Sheckly.

Elgin wiped his nose on the back of his hand. He went.

Sheck looked at the other cowboys and the communication was as clear as in a pack of jackals. They got up and vacated the table too.

Behind me, Robert Earle's twangy cowboy voice had given way to Miranda's piercingly clear tones. The song was just vocals and acoustic, the way she sounded best. She sang back to Robert Earle about why he was leaving her.

Sheck listened, his eyes on Miranda, his face complete concentration. When Robert Earle took over again, Sheck closed his eyes.

"That girl. You know I remember the first time she came up to me. One of the Paintbrush's community dances, the ones we do free for local folks every Wednesday.

She said I should come down to Gruene Hall and give her a listen. Batted those brown eyes at me and I'm thinking—this is old Willis' girl? Little Miranda?" He let his grin spread out a little. "I suppose I went down to Gruene that next weekend expecting to get me something besides a little music, but I heard that voice—you just can't get away from it, can you?"

"Unless it gets away from you."

Sheck's grin didn't diminish at all. "Let's wait for last call on that one, son."

"You don't think Century Records is serious about her?"

Sheckly followed my eyes over to the table of A & R reps. Sheck chuckled. "You think that means anything? You think they won't evaporate faster than gasoline once they learn Les SaintPierre is out of the picture? Once they learn about my contract?"

"So why wait to tell them?"

Sheckly spread his hands. "In good time, son. Let's give Miranda a chance to come to her senses on her own. Way she was talking the other night, 'fore that fool Saint

Pierre woman went crazy on me—it sounded to me like Miranda was figuring out what's what. She knows Les SaintPierre left her in a bad spot. She's looking to cover her bases."

Miranda and Robert Earle's duet came to an end. The hooting and hollering started up.

Robert Earle gave a twisted little smile when he saw the audience's response, then suggested into the mike that Miranda and him better give "Ashes of Love" another try.

Miranda laughed. The couples on the dance floor yelled approval.

"How do you mean, covering her bases?" I asked Sheck.

He spread his hands. "Nothing to be ashamed of, son. Can't blame her. She just reminded me of my offer from a few months back—asked if she was still welcome to move out to the mansion."

"She asked you."

"Sure. I said it might be a good idea, seeing as—" His eyes got that distant look in them again, like somebody had just opened the oven door and let a draft blow past the pilot lights. "Just might be better for her out there, where I can look after her, seeing as Les SaintPierre got her into such a muddle, gave her and Brent and Willis all these fool ideas about where her career should go."

"Fool ideas about how to push you out of the picture."

Sheck nodded. "And that."

I drank my Budweiser. The top of the can smelled like sausage.

"Ashes of Love" went into full swing. Robert Earle's band backed up the vocals with a good beat, bass and drums and heavy rhythm guitar. When the first verse came around Miranda let loose—her voice went up half an octave and about a million decibels to the kind of energy level she'd had at the Cactus Cafe. Her eyes closed, one hand on the mike and the other clenched at her side. Robert Earle stepped back, grinning. He played his guitar and mouthed "Ooowhee." On the now packed dance floor, the audience responded in kind.

It was impossible to have a conversation—not because of the volume, but because it was impossible not to want to watch Miranda.

That was just as well. I wasn't sure what to say to Sheck right then, what to think. I was staring at the lady onstage, thinking about a night a million years ago in a Victorian on West Ashby—in a guest room that had smelled like daisies and freon with a small cool bed and a body I hardly remembered. What I could summon up was lighter than the aftertaste of cotton candy.

The song finally came to an end. The applause was loud and appreciative. Over at the picnic table with the winecoolersipping Century reps, Milo Chavez was looking confident, pleased. He'd even managed to get one of the reps to crack a smile.

I looked back at Sheckly. "You wanted to level with me the other day. Let me return the favour. Samuel Barrera thinks you're as bad as your European friends. When he takes them down you're going to go down just as hard."

Sheck raised his eyebrows placidly. "How's that, son?"

"I don't think you're a killer, Mr. Sheckly. I don't think Julie's and Alex's murders were your idea. I think you're a mediocre black marketeer who let things get out of control.

You let some greedy professionals take over your operation and crank it into high gear. Now you're scared. You're out of your league and your local people are getting nervous. I think a year from now Jean Kraus is going to be sitting in your office, calling the shots. Either that or he's going to be long gone and you're going to be left with a very large mess where Avalon County used to be. Your friends decide Miranda's caused them any of their present troubles, you think you can really keep her out of the cross fire?"

Onstage Robert Earle and Miranda had slowed down the pace again. Keen was taking the lead on Brent's song, "The Widower's TwoStep," which Robert Earle obviously knew well. It sounded strange coming from him, though, with an edge of quirky dark humour that made the tragedy in the song seem unreal. It was now just another mymommadiedandmyhounddogwent toprison country song. I didn't like the way it played.

Over at the bar Sheckly's friends had recongregated with a few new recruits, all waiting and watching for some sign to come in for the kill.