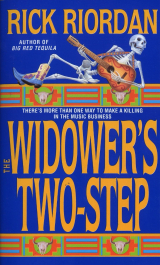

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

50

When I got back to 90 Queen Anne a gold foil package the size of two glass bricks was sitting on the porch. The card said: This will look perfect on your desk at UTSA. Good luck today. Happy Birthday.

Mother's writing. She made no mention of my failure to come to her Halloween/bythewayit'sTres'birthday party the night before. Inside the wrapping was the Riverside Chaucer, new edition. A seventyfivedollar book.

I took it inside.

I stared at some tentative notes I'd made two mornings ago for the demo class I was about to do. After last night, the whole idea seemed absurd, trivial—and oddly comforting. Students were going to attend classes today. Assistant professors were going to yawn and drink coffee and stumble through boring routines and most of them wouldn't even smell like house fires. They wouldn't see blackened bones every time they closed their eyes. They wouldn't catch themselves humming songs by the recently murdered.

With a kind of dread, I realized I wanted the class to go well.

Robert Johnson was of course sleeping on the outfit I needed to wear, so I did the tablecloth trick. Robert Johnson flipped, got to his feet, and glared at me. It took me five minutes and a full roll of Scotch tape to remove the black hair from the white shirt.

Five more minutes to tie the tie with Robert Johnson helping.

After that it's a blur.

The demo lesson did go well, I guess. I chose "Complaint to His Purse" and did the most radical things I could remember from graduate seminars—break the class into small groups, ask them to read the poem aloud while holding their wallets, ask them to write a modernday interpretation. We had a few laughs comparing Chaucer to a phone solicitor, then trying to find a Middle English phrase that was the equivalent of

"suck up." Most of the students didn't even fall asleep.

Despite my dress clothes I probably looked like I had slept on the floor the night before and spent my morning in a cemetery, but that was okay. Most of the students looked that way too.

Professor Mitchell shook my hand a lot in the hallway afterward and told me how he was sure I'd get the job. The other professors filed out without saying anything. They frowned just as much as they did during my earlier interview. Maybe tracing the etymology of "suck up" had been too much.

I drove out of the UTSA visitor parking lot feeling tingly and hollow. I was halfway down I10, doing an impossible seventy miles per hour, before I even realized I had gotten on the highway.

I took the first exit, pulled the VW into a strip mall parking lot, and shut the ignition.

I tried to get my heartbeat under control. I didn't have much luck.

I couldn't place the feeling right away—sort of like an electric generator spinning in my intestines. Not going anywhere, not hooked to anything, just making useless electricity. It was a few more minutes before I recognized it as shock. I'd felt this way a year ago, after I'd killed a man. I'd woken up a few nights afterward with this same feeling—disconnected inside, like someone else had just vacated my body and left me the shell. I told myself this was only a college lesson, for God's sake.

I started the car again. I decided to take comfort in the mundane and drove next door to Taco Cabana for enchiladas to go.

When I got back to 90 Queen Anne my favourite car was parked conspicuously across the street. Deputy Frank had the window down on his black Ford Festiva and was rubbing a finger along the top of his moustache while he read a magazine.

He might've been a little more obvious if he put wavy hands on his windshield wipers, but only slightly.

I parked the VW and walked across to his car. Frank pretended to ignore me.

In his passenger's seat was your normal stakeout gear—junk food, a camera, bottled water, a tape recorder and shotgun mike. He had his suit jacket off so the shoulder holster was in plain view. There was a black briefcase between Frank's knees.

He flipped a page of Today's Parent.

"Colic," he said, like he was talking to himself. "It's driving me crazy."

"That's rough," I agreed.

I waited. Frank turned a couple more pages. He read like he was looking at assembly instructions, his eyes flicking back and forth around the pages in no particular order, looking for the schematics on proper babybuilding.

"You supposed to be keeping tabs on me?" I asked.

Frank nodded, tapping his thumb on a picture of a new superabsorbent diaper.

"Sheckly?"

Frank nodded again.

"You want to come in for some enchiladas?"

Three times was a charm.

Frank put down his magazine, picked up his briefcase, and got out of the car.

We walked around the side of the house. My landlord Gary Hales was standing in his living room, watching out the window as I brought the man with the shoulder holstered gun and the black briefcase onto his property. Gary loves it when I do stuff like that.

I opened the door of the inlaw and Robert Johnson padded up, bumped into Frank's leg, then stepped back indignantly, his superkeen animal senses suddenly warning him that I wasn't alone.

"Hey, blackie." Frank bent down and scratched Robert Johnson's ear.

Frank apparently passed inspection. Robert Johnson began rubbing the side of his face vigorously on Frank's shoe.

Frank glanced around the room, still in read schematic mode, until his eyes came to rest on the exhibition sword in the wall mount. "Tai chi?"

I nodded, surprised. Nobody guesses correctly.

Frank waved at the futon. "Okay?"

"Sure," I said.

He sat, putting his briefcase on the coffee table. I went into the kitchen and took out the two foam boxes of enchilada dinners. Robert Johnson materialized on the counter instantly.

I got out three paper plates in wicker plate holders. Two enchiladas for me, one for Frank, one for Robert Johnson. Flour tortillas and beans and rice and grease all around.

I took the food into the main room, set Robert Johnson's on the rug, and handed Frank his.

Frank sat forward on the futon. He rolled a tortilla into a tube, dipped it in enchilada sauce, and bit the end off.

"Enough's enough," he said. "The briefcase has some prelims from the M.E. on Brent Daniels, some paperwork I borrowed from Hollywood Park on Alex Blanceagle.

There's also some other cases from the Avalon Department where"—he stopped, considering—"where Sheckly's name has figured prominently."

"And you're showing all this to me?"

Frank read the wall. He chewed his tortilla. "Some guys I know at Bexar County—Larry Drapiewski, Shel Masters—they tell me you're solid."

I tried not to look surprised. Larry and Shel didn't always tell me I was solid. The adjectives they used about me much more frequently had to do with gas or liquid.

Frank must've caught them at a weak moment.

"You should be giving this to Samuel Barrera," I suggested.

Frank gave me a brief smile, then he slid the briefcase toward me across the table.

"But Barrera would feel obliged to say where he got the information," I continued. "You need someone who can take a little heat off you."

He finished his tortilla, wiped his fingers, then stood up.

"Shame you didn't come home today," he speculated. "I'll wait until midnight, then decide to call it quits. Agreed?"

I nodded. "Good luck with the colic."

Frank actually smiled. "Yeah. And, Navarre—I hear things at the department. Elgin, some of the other guys who were at Floore's last night. They're hoping you come back into Avalon County sometime when they're on duty. If I were you, I wouldn't do it."

When Frank was gone, I kicked off my Justins and let my toes expand to their normal size. Robert Johnson came over and discovered that his head fit perfectly in a size eleven boot. He shimmied in up to his waist and stayed that way, his tail flicking back and forth.

"You're weird," I told him.

His back legs padded a few times. The tail flicked.

Then I remembered I wasn't supposed to be home.

That left several options, none of them pleasant. I reclaimed my boots and headed out toward Monte Vista.

51

When I got to the SaintPierres' house the realtor was just leaving.

"Mr. SaintPierre?" she asked.

Her tone was mildly amused. She held the front door open for me with just her fingertips, up at ear level, the way my mom used to hold up my dirty Tshirts, asking if I could get them in the hamper for once.

"Thanks," I said.

"I made some sketches." She wedged her clipboard snugly under the arm of her rottenapple brown blazer. "The house has marvellous flow patterns."

"I've always thought so."

She nodded, pursed her lips, then appraised the front of the house one more time.

"Well, I'll get back to you."

"Allison gave you a time frame?"

"She said immediately."

"Perfect."

She gave me another amused smile—probably never met a talent agent before—then offered me her business card. Sheila Fletcher &c Associates. The ink was the same colour brown as her jacket and her nails. She waved three fingers at me as she walked down the driveway and got into her Jeep.

Sure enough, the interior of the house had great flow patterns now. Easy when there was nothing to flow around. The white sofas and the artwork pedestals were gone. The Oaxacan wall hangings had been removed so the walls were all white paint and windows. Six million moving boxes were stacked by the door.

The bar was still set up, however, and there were two glasses on it, one sticky with lipstick and bourbon residue, the other half full of tepid water. The fireplace had been used the night before. The smell of smoke lingered from the poorly working flue. After the previous night, smoke was not a smell I was glad to encounter.

I went upstairs and started checking the bedrooms. The first was packed. In Les' room the fourposter bed was stripped, the roll top desk taped shut, his closet empty. I opened one of the moving boxes packed in the corner. Les' Denton High School yearbook was on top.

"What the hell are you doing?"

I turned and found Allison was in the doorway.

She'd raked her blond hair into stiff wet rows, rinsed but not shampooed. Her complexion was pasty, the corners of her eyes unhealthy red. Her figure was totally hidden under a man's white dress shirt and baggy khakis. Maybe they were Les'. The shirt was speckled with some light brown liquid.

"Glad I caught you before you left town," I said.

She glared at me. "Get the hell out, Tres. Isn't it enough—"

She faltered. She waved her hand vaguely north, in the direction of the Daniels ranch.

I nudged the moving box with my foot. "The realtor says you're moving out immediately."

"Is that any of your business?"

"Possibly."

She grabbed her forearm with her opposite hand like she was covering a wound. She looked past my shoulder. "I'm renting the house, all right? I can cover the mortgage that way until the sale can happen. It's about the only choice I had."

"What happened to taking over the agency?"

Allison laughed. Her voice was suddenly quivery. "Milo's been real busy with Miranda, but not too busy to bring in some lawyers. Why don't you ask him?"

She stepped inside and sank down on the edge of the stripped mattress. She stared at the boxes of Les' things.

"Who did you have over last night, Allison?"

"That is definitely none of your business."

"You're going to need an alibi."

She opened her mouth. She searched for something to say but couldn't quite find it.

"Arson with murder is almost always to cover traces," I said. "Homicide done hastily, by somebody who flew off the handle. Who does that sound like?"

She made a small croaking sound. "You think—"

"I don't think," I said. "But it doesn't look good—you packing up and moving out. If I was the detective in charge of Brent's murder, maybe with Tilden Sheckly paying me to find a convenient solution, I'd start with you. Your husband disappears, your lover gets torched, you've got a history of violent, unpredictable behaviour. I doubt many people would come to your defence."

She hugged her arms. "I've got nothing. Brent is dead. Les is gone, Milo's got the agency, and I've got nothing. Just leave me alone, okay?"

She leaned forward until her face was almost over her knees.

I counted to ten.

It didn't help.

"Get up." My own voice sounded strange. "Come on."

I grabbed Allison's upper arms and lifted her to her feet. She was heavy—not dead weight, but her bones seemed to be lead. I had to use most of my strength to keep her from twisting out of my grip. Finally she succeeded and pulled away. She stood there, weteyed, rubbing the white stripes on her arms where my fingers had been. "You fucker."

"I don't appreciate the selfpity. It's not going to get us anywhere."

"Just get out, Tres. You hear me? I used to think you were all right."

She glared at me, willing me away, but the anger was unsustainable. She took a long shaky breath and looked around at the boxes again, the roll top desk, the blank walls.

Finally he sank back down onto the bed.

"I'm so tired," she murmured. "Just go away."

"Let's get you out of here. Let's do something constructive."

She shook her head apathetically. When I sat next to her, Allison leaned against me—nothing personal, just like I was a new wall.

"I'm moving home to goddamn Falfurrias," she said. "Can you believe that? This house can buy me about six of the nicest houses down there. I can raise cows. Listen to crickets at night. Isn't that insane?"

She looked up at me. Her eyes were watery.

"I'm the wrong person to ask."

She laughed the word shit. "You never give me a goddamn straight answer, do you?

Where is Miranda?"

"Staying safe."

"In your apartment? Sharing that little futon?"

"No. Not with me."

Allison looked at me uncertainly. She heard the finality and the edge of bitterness in my voice and she didn't know quite what to do with it. She started to get up but I held her shoulder, not forcefully.

I'd like to say that from there events took their own course and I was caught by surprise. But they didn't and I wasn't.

I kissed her.

For once Allison SaintPierre didn't put up a fight. She eased into the kiss with a kind of exhausted relief.

After a long time she leaned back into the bed and I went with her. She bit and kissed and breathed in my ear as I tried futilely to work the first button on the massive white dress shirt until she laughed and whispered, "Forget it."

She sat up just enough to get the shirt off overhead. Then she pressed against me again and felt twice as warm, almost feverish. Her back was all goose bumps.

We rolled around on Les SaintPierre's bed and with each new angle the most exposed piece of clothing was kicked or pulled or cursed away. I think Allison stopped crying by the time the clothes were all gone. Her skin was uncomfortably hot except for her fingers. Those were icecold.

There was some unstated agreement that this love making would require nonstop movement, not necessarily frenzied but definitely continuous. Stopping would lead to thinking and thinking would be bad. We took turns crushing each other into the slick, uncomfortably bumpy surface of the mattress, little pinprickers of rayon stitching needling us in our backs. The room was air conditioned but we quickly became sweaty and noisy until the sounds became an uncontrollable cause for the giggles and then almost as quickly stopped mattering. We rolled a little too far, off the side of the bed. I remember something about a pain in my elbow but that didn't matter much either. We readjusted and sat facing one another, Allison's chin at the level of my mouth and her feet curled against the small of my back. Allison hugged me very tight with her arms and legs and buried her face in my neck and trembled quietly, as if she were crying again. I inhaled sharply and joined her and my body didn't know to stop the movement until Allison's muffled voice spoke into my neck. "Please—okay. Okay."

We stayed still then, feeling each other breathe until the rhythm of our lungs slowed and the hardwood floor began to feel uncomfortable. Our skin separated in places like candle wax being peeled away.

Allison smushed her nose against my cheek and rubbed around until her lips connected with mine. When I kissed her the second time I kissed teeth.

"When you say 'let's do something constructive,' Mr. Navarre—"

"Shut up."

She laughed, pulled her face away, and cupped my ears lightly with her fingers. "Didn't happen."

"Of course not."

She kissed me again. "You're still holding out on me for fifty thousand dollars."

"You're just trying to get the money."

We showed each other how much we detested each

other for a while longer.

At some point I remember looking up and seeing the Latina maid in the doorway, but when I opened my eyes for a better look she was gone, just a momentary vision of bored, aging eyes in an impassive face, showing more irritation than embarrassment at the gringos on the floor of the stripped bedroom, giggling foolishly and muttered little

"I hate you’s.” Maybe to the maid we were just one more item she would be glad to be rid of when the house passed to more respectable owners.

52

"I liked the Audi better," Allison told me.

We were sitting in the VW with the top up, the windows open, but not a bit of circulation coming through. The afternoon had turned thick and gray and lukewarm. Nothing interesting was happening at the warehouse across the street.

"What is this?" I asked. "Number seven?"

"Five," she corrected, pushing up the sunglasses. "It just feels like seven."

I borrowed the list of addresses from her, a photocopy of the document we'd found in Les SaintPierre's boat shed. I scanned the page. A total of twentythree addresses just in San Antonio. At this rate it would be way past Friday before I even had time to find them all, much less figure out ways to get inside and see if they had value to the case against Sheckly. Sam Barrera could have probably put his agency into high gear and gotten the job done in one afternoon if he hadn't had legal restrictions to deal with.

Sam Barrera could go to hell.

So far all the addresses were storage facilities or trucking yards. Not all of them said Paintbrush Enterprises on the gates but I had a suspicion Tilden Sheckly or his friends from Luxembourg had a stake in each, one way or another.

Each address had a date next to it. Allison and I had started the search with the location closest to today and worked our way forward in time. We were now on November 5, four days from now. The address was in a light industry park in the elbow of land where Nacogdoches met PerrinBeitel and became, in true Texas creative thinking, NacoPerrin.

The storage facility consisted of a pair of long parallel buildings, painted army green with mauve trim. The inwardfacing walls were lined with steel rollup doors and stubby loading docks and were just far enough apart that a semirig could back in and deposit its freight box on either side. The asphalt between the two buildings was scarred with large black semicircles from truck tires. It looked like somebody had been in the habit of drinking from Godsized Coke cans there and hadn't had the sense to use coasters.

The complex was ringed with tenfoot chain link, no barbed wire at the top but a security guard in a booth at the front gate and good night lighting all the way around. In the day, traffic on the back side of the industry park was heavy—a constant stream of cars cruising NacoPerrin's ugly strip malls and fastfood restaurants. On the entrance side of Sheckly's facility, traffic was lighter. The only neighbour was a sulfurprocessing plant across the street, acres of weed, and mountains of moon dust.

At the moment the guard at the gate wasn't very interesting to watch. He was reading a little magazine, Security Guard's Digest probably. The gates were closed and there were two detached freight boxes in the yard in front of closed loading doors. No business in or out.

Allison sighed. "This is better than staring at the walls at the old house. But only slightly."

Before we'd left Monte Vista, Allison had started referring to her home of two years as the old house. When she'd plopped into the shotgun seat of the VW she'd insisted that she was completely all right, over Les, finished grieving for Brent, ready to help me, and convinced that our afternoon together had been nothing but a nice little break from reality. I wasn't buying any of it and I don't think she was either, but it did let us set aside weightier issues so we could concentrate on watching empty loading docks.

I was about to suggest trying address number six when a white BMW sedan cruised past us on Nacogdoches. It slowed, then turned at the gate. The security guard immediately discarded his magazine and came out to the driver's side window.

"Ignition," I said.

Allison sat up and looked.

Jean Kraus rolled down the BMW's window and spoke to the guard, who nodded. Jean spoke again, smiling, and the guard nodded even more vigorously.

The guard trotted up to the gate, unchained it, and swung open one side. The white BMW drove through. Jean Kraus parked next to the first trailer and he and two other men extracted themselves from the sedan. Jean was dressed for success—an Armani suit, beige, with a little black tie and plenty of silver accents. The other two men I didn't recognize. One was well built, Anglo, with curly brown hair and dress slacks that didn't match the sleeveless Tshirt. The third guy was taller, older, a black sweat suit and the remnants of black hair.

Jean seemed to be pointing out some things to the men, giving them the tour. After a fiveminute conversation and some head nodding and a few looks at the loading bays, all three got back in the BMW and left.

"They're moving cargo out," I said. "Getting rid of it early."

Allison looked at me. "Are we being constructive yet?"

"We're on the outskirts."

I started the engine of the VW.

We followed Jean's BMW for a few miles down Perrin Beitel before it became too difficult. The traffic was bad, Jean was a little too jumpy a driver, and my orange bug was anything but nondescript. To stay with him I had to risk discovery. I fell back and let him go.

"Does this mean we don't get to beat the shit out of anybody?" Allison wanted to know.

"I'm sorry, honey."

Allison pouted.

It was starting to get dark when I dropped her back at the old house in Monte Vista.

Allison insisted on staying there and she insisted on staying there alone. I didn't argue very hard with the second part. Seeing her get out of the car, I started developing a funny empty feeling in my intestinal basement that either meant I very much wanted to stay with her or I very much didn't. You get to feeling those extremes and not being able to tell them apart, it's time to go home by yourself and feed the cat.

I watched her walk all the way up the sidewalk and go inside and I watched the door for a long time after that. The door didn't reopen.

When I got home I showered, picked the cleanest things I could find out of the growing pile of laundry, then made two calls.

Ray Lozano answered at the Bexar County M.E.'s office.

"Raymond. This is Tres."

A moment of silence. "As in the guy who owes me the Spurs tickets?"

"Yeah, about that—"

"Save it, Navarre. You keep making promises and I keep believing, it'll just make me feel bad."

"Faith is an admirable quality, Raymond. You like the Oilers?"

"What do you want?"

I read Lozano the notes Frank had given me from the Avalon County autopsy of Brent Daniels.

"So?" he said.

"What can you interpret?"

"They were lucky to get as much tissue as they did, given the state of the body. It sounds like this guy was dead before he burned. No soot particles in the bronchi. No carboxyhemoglobin in the fluids. This guy didn't go down breathing smoke."

"And the lack of a positive ID?"

"Somewhat unusual, given that they know the victim, but it's early. They have to be one hundred percent sure. If you have to wait for Xray records from a big hospital, or wait for the odontologist, maybe the anthropologist to come down from Austin, it can take up to ten days. Sometimes more. It doesn't sound like there's really any doubt, though. The size is right, compensating for shrinkage; age and sex are right."

"What about these trace chemicals?" I read off some hardtopronounce compounds the M.E. had found in the few remaining fluids of Brent's body.

Lozano ticked his tongue a few times. "I'd have to check with a toxicologist. Was this guy an alcoholic?"

"Probably. Yes."

"Okay—that gives you a setup for liver damage, poor sugar processing. If the guy came in contact with certain other drugs in a large enough dosage, they could trigger the kind of chemicals you're seeing there, only that would mean the subject was in a diabetic coma before he died."

"A coma. You mean like if he came into contact with diabetes drugs? Gluco somethingorother?"

"Glucophage. Absolutely."

I was quiet so long Lozano finally said, "You still there?"

"Yeah. You think—would somebody OD on these, for suicide?"

Lozano blew air. "Not unless they were mainline stupid. Chances are pretty good the drugs wouldn't kill you, they'd just turn you into a vegetable. I know one nurse at the Medical Centre that happened to, man—alcohol and diabetes medicine. They're changing her diapers three times a day now. Plus it wouldn't make sense—a guy goes comatose, then dies, then becomes a crispy critter."

"Okay."

"That information helpful at all?"

I probably didn't sound too enthusiastic when I said, "Yeah. It's helpful."

"Now what was that about the Oilers?" Lozano started to say. But the phone was already halfway to the cradle.

Milo Chavez was even more thrilled to hear from me.

"Tell me Miranda is safe," he demanded.

"Miranda's safe."

"Tell me I shouldn't kill you for taking off with her like you did."

"Come on, Milo."

"I had a couple of Avalon County dicks in the office this morning, Navarre. They had some questions about how Les and I got along with Brent Daniels, why I might've hired a PI and what kind of work you did, whether you were licensed or not. I didn't like the direction they were going."

"Avalon County homicide couldn't detect its way out of a cascaron, Milo. They're just trying to rattle you."

"They're succeeding."

I told him about my afternoon—about the autopsy files from Frank, then about the warehouse address I'd visited on PerrinBeitel.

"I know that place," Milo said. "This is good, isn't it? The RIAA guy, Barrera—he'll need to move on it now, right?"

"You ask Barrera, he'll tell you nothing's changed. There's still no evidence, no probable cause for a search. Just the fact I saw somebody there who I didn't like isn't enough. Barrera's willing to hold out another few years if it means strengthening his legal case."

"I've got until Friday," Milo muttered. "And you're talking about years."

"Barrera's technically correct," I said. "There's nothing they can move on in what I've found. At least not right away."

"Technically correct," Milo grumbled. "That's just great."

"We'll figure out something," I promised.

"And Les?"

That one was harder to sound confident on. "Consider him gone. For good."

Milo was silent, probably trying to formulate some kind of B plan. When he spoke again his voice was strange, tightly controlled. "I'll need to talk to Miranda. If we're going to have to come clean with Century when we bring them the tape, I need to talk to my client about strategy. She needs to know the risks. Maybe—"

"I'll bring her by later tonight," I promised. "It'll take a couple of hours."

"My office at nine," he suggested.

"Okay. And Barrera is good, Milo. The people he is working with are good. They will eventually put Sheckly's ass in a sling."

The other end of the line was deadly calm.

"Milo?"

"I'm fine," he said.

"Let it go, Milo."

"All right."

"Your office at nine."

Milo said sure. As he hung up he was still speaking, muttering unhappy and angry thoughts. I had the feeling I was no longer part of the conversation.