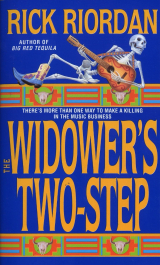

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

55

I remember Jean Kraus raising his Beretta toward Sheck and Sheck drawing his .41 faster than anything I've ever seen and both men firing. Three rapid red bubbles expanded and burst in the back of Kraus' white turtleneck. Kraus lurched backward into a forest of upright CD spools and sent them crashing to the floor. Plastic caps shot off and three CDs spilled out like metallic poker chips, slishing colourfully across the cement. Three.

The aftermath was incredibly quiet. The rain drummed on the corrugated metal overhead. The truck engines hummed. I swear I could hear the rattle of Milo's breath.

Sheck stared at me. His eyes were dull. He wiped the sweat off his lip with the back of his gun hand, took a step back, and stumbled against the crate where he'd been hiding a moment before. There were giant sweat rings like halfmoons under the arms of his denim shirt. One of his boots had come untucked from his jeans. His hat was knocked sideways at a funny angle and he was bleeding—from the scar Allison had given him a few days ago, now burst out of its little squares of tape, and from a streak of blood on his arm, where Jean's bullet had grazed through the shirt, ripping the fabric and a layer of skin neatly away.

The sirens were getting louder.

I looked at Jean Kraus' body in the CDs. He was bent over the tubes of music at a funny angle, his head too far back and his chest too far out. One of the canisters had fallen into the crook of his arm so he seemed to be holding it like an oversized spear.

One leg was folded unnaturally behind him. His eyes were open as black and fierce as ever.

I crouched next to Milo and looked into his face. I couldn't tell anything. He continued to breathe, and to bleed. The wound was in his shoulder, probably no internal organs hit. His eyes were glazed and unfocused.

I looked at Sheck.

He was breathing shallowly, like he was trying to remember how. When he looked at me and laughed, the noise sounded more like a pained whimper, like he was getting something cauterized.

"I can talk, son," he told me. "I'll talk. Hell, I've weathered worse."

As the sirens approached and I tended to Milo's wounds Sheckly paced around the warehouse, kicking at the pirate CDs, laughing and mumbling to Jean Kraus' corpse that he'd weathered worse, like maybe if he said it a few hundred more times he might come to believe it.

Tuesday and Wednesday were a blur. I remember cops, Milo Chavez in the hospital, more cops. I remember sleeping in an interrogation room for several hours, speaking to Sam Barrera and Gene Schaeffer on several occasions and meeting Barrera's nice friends from the FBI and ATF. When I dreamt I dreamt about giving pints of blood over and over and asking for donuts and water and getting nothing but little smiley face stickers that said: I'M A DONOR.

I woke Thursday morning on the futon at 90 Queen Anne, wondering how I got there.

Vague memories started surfacing about a ride in the back of a mustard yellow BMW, someone who smelled like Aramis cursing my father's name as he trundled me out of the car and dragged me up the stairs and tucked me roughly into bed.

I blinked the crust out of my eyes. Robert Johnson was curled around my feet. The TV

was on.

I stared at the pretty colours and the plastic faces of anchor people. Slowly the sounds they were making became English.

They were recapping the story of the week, telling me things I already knew. We'd had the second largest bust of pirate and bootleg audio CDs in U.S. history, right here in the Alamo City—$1.5 million netted in cash over the last two days and 350,000 titles by over ninety country artists—all precipitated by a police response to gunfire at a North Side warehouse Monday evening. Three men had been killed before police arrived. One of the victims was an Avalon County deputy who'd apparently been in collusion with the pirates. The other two victims were Luxembourg nationals. A falling out among thieves, one reporter had called it.

Tilden Sheckly, country music entrepreneur, had been taken into custody at the scene and was cooperating with authorities about his connections to the European smug

gling ring. He had led Customs officials to three separate warehouses full of merchandise and cash and several boxes of automatic weapons that the ATF claimed were the first shipments of a fledgling gunrunning operation, piggybacking off the CD

distribution network. Several recent murders in the San Antonio area had now been linked to the Luxembourg organization and at least one foreign national was still at large, wanted for the slaying of the Avalon County deputy Elgin Garwood. The anchorman showed the wanted man's face—the third man who'd been in Jean Kraus'

BMW—and gave a name I didn't recognize. The murder weapon had been found several blocks away—a .357 calibre pistol, wiped of prints, unregistered.

A search was under way for locally based talent agent, Les SaintPierre. According to Samuel Barrera, RIAA's contracted private investigator and hero of the day, Mr. SaintPierre was not a suspect in any crime. Rather, SaintPierre had disappeared while acting as an informant for the authorities and was, sadly, presumed dead.

As for Tilden Sheckly, he was a small fish. When pressed the SAPD spokesman confirmed that Sheck stood a good chance of lenient charges if, as promised, he could help authorities in several states and at least three E.U. countries with information on his Luxembourg partners.

I turned off the TV.

I managed a shower, then some cold cereal.

Around ten o'clock I called a friend of mine in the ExpressNews entertainment section and got the rest of the story. The inside scoop in music industry circles was that Les SaintPierre had actually embezzled tens of thousands from his own agency and disappeared to the Caribbean. Some said Mazatlan. Others said Brazil. Many said he'd been working with the Luxembourgians. The agency he'd headed had collapsed over the last forty eight hours, although one of Les' associates, Milo Chavez, had heroically confronted the pirates and blown the whole operation open. Chavez was said to be recovering nicely and putting together a lucrative deal for Miranda Daniels with Century Records. As a result of that, and the good publicity, Chavez had employment offers from several large Nashville agencies. Reportedly with Milo would came Miranda Daniels as a client and a large number of former SaintPierre talent.

Milo had apparently underestimated himself.

According to my friend at the ExpressNews, the Miranda Daniels developmental tape featured strong material and was as good as a surefire gold record. It had a strong buzz going, whatever that meant. My friend expected the deal to go through with Century Records and Miranda to be on the Billboard charts by New Year's. He said the human interest angle really helped– first and foremost the recent tragic death of Miranda's brother, who had written some of her best songs. The murder of her former fiddle player helped too.

"The tabloids are eating this up," Carlon McAffrey told me. "You don't happen to have an in with this Chavez guy, do you? Or Daniels?"

I hung up the phone.

I did tai chi on the back porch until almost noon. Halfway through the long form my muscles started to burn the right way again. The vacuous sick feeling in my stomach faded. Once I got into the sword form I could almost concentrate again. The phone rang just as I was completing the last section.

I went inside and caught it on the third ring.

Kelly Arguello said, "Allen Meissner."

"What?"

"Get a pen, stupid."

I pulled one out of the crack in the ironing board. Kelly rattled off a social security number, a Texas driver's license number, a flight number.

"Meissner applied for the social security number two months ago," she said, "at age fortyfive. Got his license at DMV two weeks ago, then plane tickets to New York on American, booked for tomorrow. Good trick considering the guy died in '95. Meissner used to be an inhouse auditor for Texas Instruments."

"Holy shit," I said.

"You did say before Friday, didn't you?"

"You found him."

Kelly laughed. "That's what I've been trying to tell you, chico loco. Your client's going to be happy?"

I stared at the flight number. "When was this reservation made?"

"Yesterday. Hey—this is good news, right?"

I hesitated. "Absolutely. You're incredible, Kelly."

"I've been trying to tell you that, too. Now about that dinner—"

"Talk to Ralph."

"Oh, please, not that again."

I leaned down against the ironing board and ran my fingers into my hair. I closed my eyes and listened to the slight crackle of the phone line.

"No," I said. "I mean you should call him."

She spent a few silent moments trying to interpret my tone. "What happened? What'd you two get into this time?"

"You just need to call him, okay? Even better, get down here. Spend a day with him, okay? He needs—I don't know, I think he needs to be reminded you're around. Some niecely influence."

"Niecely is a word?"

"Hey. English Ph.D. here. Back off."

"This is the thanks I get for helping you?"

"You'll do it?"

Kelly sighed. "I'll do it. I'll also come to see you." She said it like it was the deadliest threat she could make. I smiled in spite of myself. "Bueno?" she asked.

"Bueno," I agreed.

56

It was Friday morning before I spoke to Milo and Miranda again. I never found out how Miranda's things got picked up from the safe house on the South Side—Ralph just handled it somehow. Ralph didn't call me. That told me something.

Milo and Miranda arranged to meet me at the Sunset Cafe for breakfast. Gladys the exreceptionist for the ex Les SaintPierre Agency set up the appointment.

The Sunset Cafe was the kind of place you'd drive right by—an adobe oneroom shack on the ridge rising from Broadway, wedged between an art gallery and an insurance office. Despite its name, the cocina opened early and closed early, serving egg and bacon and came guisada tacos and strong coffee to blue collars. When I pulled the VW up the steep driveway and into the tiny parking lot, Milo's Jeep was already there.

The Daniels' brown and white Ford pickup was also in the lot, minus the horse trailer.

Willis Daniels was sitting in the driver's seat. If he noticed me walking up, he didn't let on. At least not until I stood at the window for a few seconds.

The old man looked up from his book and smiled a tight smile. "Mr. Navarre."

He offered to shake, gentlemanly. His hand lacked any of the energy it had had when I'd first shaken it, outside Silo Studios a hundred years ago.

"You not hungry?" I asked.

The smile took on a kind of sad amusement. "I'd just be in the way. You go on."

He went back to his book, sighed. It would've been easier if he'd yelled at me, or frowned at least. I went inside.

Milo and Miranda were drinking coffee at the table by the window.

Saying Milo looked nice is superfluous, but somehow there was shock value in seeing him immaculate again after the way he'd looked on that warehouse floor, then in the hospital bed. His trousers were dark and freshly pressed, his white shirt crisp with starch. The bandages underneath the shirt made his left shoulder look bulkier than the right. He was wearing a diamond stud earring and his shortcropped black hair looked freshly trimmed along the edges.

He hooked a pink chair with his fingers and dragged it out from the table.

"Have a seat, Tres."

I sat between them.

Miranda was wearing lightly tinted round sunglasses. She'd chosen all white today—long skirt, blouse with just enough motherofpearl studs to put it into the Western category, white anklelength boots. Even her hair, dark and curly, was pulled back in a white headband, making her forehead look high and her sunglasses that much more obvious.

She was looking into her coffee, holding it with both hands. She glanced up briefly at me, then down again.

"Here." I set my shoe box next to Milo's untouched plate of tinfoilwrapped tacos.

Milo scowled, lifted the lid, then closed it again.

At a table across the way one of the construction workers had apparently seen what was inside the box. He said, "Holy shit" very quietly and nudged his friend.

"You brought me cash?" Milo asked, incredulous.

"That's the way I found it."

Milo looked at me, a little puzzled by my tone. "All right. Fifty thousand?"

"Half."

He looked at me longer.

"Problem?" I asked.

"Very possibly."

"The rest I'm giving to Allison. The way things are shaping up, it may be the only thing she gets out of this deal."

Milo let his eyes slide over to Miranda, who looked suddenly very sad.

"Allison," Milo repeated. "You know that this is agency money, Les' and mine. You know she doesn't have claim to it—why the fuck—"

"You want to talk to the IRS, go. I'm sure you were planning on reporting this recovered."

Milo closed his mouth. His eyes had the bull fierceness in them, but he was trying hard to keep it from the surface.

"I hoped we could be a little more constructive here. I didn't want—" He shook his head, disappointed. "Christ, Tres, it's not like we don't owe you something, but—"

He let me see a little bit inside, a little bit of hurt and discomfort, the sense that we were still friends.

I turned to Miranda. "You happy with your deal?"

The question took her by surprise, or maybe it was just the fact that I spoke to her at all.

She sat up, away from me just slightly. "I will be, yes. I'm grateful to you. But—"

She was steeling herself to say something, probably something she'd rehearsed with Milo before coming here.

She couldn't quite manage it. She swallowed and looked on the verge of tears. It was a look she did well.

"Miranda's relocating to Nashville," Milo supplied. "We both are."

I turned my attention back to him. "You both are."

Somehow the words seemed absurd. I felt like I was speaking Spanish, when I hit an unfamiliar colloquialism and the sense of almost being fluent came to a grinding stop.

Milo unwrapped one of his tacos, peeling back the tinfoil with the detached interest of a coroner. A plume of steam zigzagged up from the eggs.

"We've been lucky things have worked out as well as they have," he explained. "Very lucky. We owe you for that, but we thought it would be best—Miranda needs to be closer to the action."

I stared at Miranda. She wouldn't meet my eyes.

"We just wanted you to know," Milo continued. "There's a lot of outstanding problems from all of this. Until Miranda's career really gets going, things are going to be fragile.

Miranda needs a clean break from everything that's happened."

I kept staring.

"She's lost family here," Milo continued. "She can't keep being reminded of that. We want to make sure you feel compensated, but you need to be out of the picture, Tres.

I'm going to insist on that."

"Compensated," I said. Another foreign term. I looked at Miranda. "You plan on compensating the others, too—Cam, Sheck, Les? How about Brent and Julie Kearnes?"

Miranda wiped a tear away. She was wavering between sorrow and anger, trying to decide what approach would be the most effective.

"That ain't fair, Tres," she muttered, hoarsely. "It just ain't."

I nodded. "How long until Milo gets the cleanbreak message, from somebody in Nashville, some slightly bigger big shot who's decided he can look out for your interests better? A week ago you told me Allison was the only person who scared you to death, Miranda. I've met somebody scarier."

"Stop," Milo insisted.

He was strictly lawyer now. Our relationship was about thirty seconds old and would fade as soon as the conversation was over, like finger pokes on bread dough.

I stood to leave. The waitress came over and offered me coffee apologetically, apparently thinking she'd been too slow. When I didn't respond she raised her eyebrows, offended, and walked away.

"You kept your promise, Chavez," I said. "You made sure things didn't work out like last time."

I walked outside.

When I got to the car Willis Daniels didn't even bother looking up from his book. He was smiling his peaceful, Santa Claus dayafterChristmas smile.

Through the window of the Sunset Cafe I could see Miranda crying, Milo's huge hand on her shoulder. He was speaking to her reassuringly, probably telling her she'd done what she had to. That it got easier from here.

There was nobody in the VW to do that for me.

It was just as well. I would've slugged them.

I turned right on Broadway and headed for the airport. I had a plane to say goodbye to.

57

San Antonio's main terminal was lollipopshaped– a long corridor with a carousel of gates at the end. At the centre of the circle was a magazine kiosk and a pricey snack shop and a souvenir stand where you had your last chance to buy authentic Texas pickled jalapenos and stuffed armadillos and rattlesnakein plastic toilet seats.

The American flight for New York would be departing from gate twelve. I was an hour early. A flight from Denver had just deplaned—a few businessmen, a couple of college kids, lots of pale retirees, winter Texans.

I got myself a fourdollar draft beer at the bar and sat at a table behind a row of bromeliads, facing the gate. At the table next to me a couple of outofuniform airmen were trading stories. They'd just been let out of basic training at Lackland and were heading home on leave for a week. One of them was talking about his wife.

Nobody I wanted to see came to the gate. The desk wasn't checking anybody's tickets yet. A couple of stewardesses ambled out of the gate, all blond hair and long legs and wheeled luggage. The overweight captain walked behind them, appreciating the view.

Over by the window a little Latino kid who reminded me a lot of Jem was putting his face against the glass wall of the observation area. He blew his mouth against the glass until his cheeks puffed out, then ran a few feet and did it again. The glass was a smudgy drooling foggy mess for a good twenty feet. Dad was a couple of rows away, watching sports coverage on an overhead TV. He probably wasn't much older than I was. The kid was probably five.

Finally a ticket checker changed the signs on the gate display. NEW YORK. ON TIME.

He clacked a few keys on his computer terminal, then joked a little with one of the airport custodians.

Passengers started to arrive.

The airmen got up and left, shaking hands. One was heading to Montana. I didn't know about the other.

I bought another fourdollar beer.

The little Latino boy got tired of sliming the windows and came over to climb on his dad. Dad didn't much care. Pretty soon it looked like Dad was growing a small pair of flailing blue Keds out of his shoulder blades.

Finally the newly christened Allen Meissner arrived, twenty minutes before flight time, just before the airline would start preboarding. He was wearing a cowboy hat that shaded his face pretty well and clear glasses and faded denim clothes that weren't his normal look. He'd dyed his hair a shade or two lighter and I suspected that his cowboy boots were a little taller than they needed to be. He'd taken lessons on how to disguise himself, just like he'd taken lessons on how to construct his new paper identity. He wouldn't have attracted any casual onlookers. He would've stood a fair chance of slipping by any random encounters with acquaintances, unless they knew who they were looking for. I did. He was definitely my man.

The new Mr. Meissner was travelling light—a single backpack, dark green. It was pretty much exactly like mine.

I walked up behind him as he was getting his boarding pass.

I let him check in, answer the questions, mumbled thank you to the attendant. When he turned around he ran into me at such short range that my face didn't register. He started to plow around me, the way strangers do, just another bumper in the pinball game.

Then I took his upper arm and backed him up.

He focused on my face.

"Hey, Allen," I said.

I've seen a lot of shades of red in my time but never one quite that bright, quite that quick to take over a complexion. I'm not sure what Brent Daniels would've done if we'd met under different circumstances, but here in a crowd, without a backup plan, he was stuck. It was my call.

"Buy me a beer," I said.

For one second I really thought he was going to bolt. His knuckles on the strap of the backpack went white. Then he shoved past me, angry but slow—heading for the bar like a kid who'd been told to go to the principal's office and knew the way by heart.

We sat at the same table I'd been occupying. My seat was still warm. Brent slid across from me with a beer. One for me—none for him. He passed the beer over and then waited for my reaction, like I might tell him he could go now.

I didn't.

"New York," I said. "Where then?"

Brent let out a little hiss of air. He looked strange with the fake prescription glasses, older somehow. He also looked strange because for the first time, he'd taken pains with his appearance. Real pains. He was closely shaven and immaculately clean. Not bad for a guy who had been a charred pile of ashes a few days ago.

Apparently a few papery lies floated through his mind before he decided not to try them. Finally he just said, "I don't know."

"Les hadn't thought it that far ahead?" I asked. "Or you just don't know what he had planned?"

Brent shook his head. "What do you want, Navarre?"

He didn't sound very anxious to hear the answer.

"I don't need a confession," I said. "I know the basics. Les had to go somewhere when he got scared away from his hiding place on Medina Lake. He'd already decided you were a kindred soul—you'd spent time together, you didn't give a damn, you knew what it was like being a shell. You also knew what it was like getting suckered into something by Miranda."

I waited for him to contradict me. He didn't.

" Les came to you and you agreed to put him up in the upper room of the apartment.

Maybe a week and a half ago?"

Very slightly, Brent nodded.

"At some point, Les got drunk. Then he got stupid. He was a pill popper. He thought he recognized something in your medicine cabinet—something cosmetically similar to one of his favourite drugs. He took it and collapsed– diabetic coma. Maybe he didn't die right away. Maybe he stayed in a coma for a while, but eventually you realized you had a dying human vegetable on your hands. Les already had plans, had an identity, had money and an escape and everything he needed to get a new start. A man in his forties, with money and no connections. Les didn't need it anymore, so you decided you'd take it. Brent Daniels didn't have much of a future, did he? And he sure as hell didn't have much of a past. You burned his body in that tractorshed apartment along with Brent Daniels' identity."

Again I could only judge the truth of what I said by Brent's eyes. Nothing snagged in his expression. He let it roll over him, not pulling back, not giving any indication anything was wrong. Or maybe he was just too dazed to let any reaction show.

"That's why Les never collected his fifty grand from the boat shed. He wasn't alive to do it, and you didn't know anything about it. How much did you know about, Brent?

With the keys to Les' new identity, maybe a change of photo or two—you could have whatever you wanted. To make it work, you must have access to at least a few of the late Mr. Meissner's accounts."

"You want to go now?" he asked. It was clear the "you" was actually "we," that he expected somebody to put on the cuffs.

"No," I said.

Brent stared at my beer. He let his shoulders sag down under the weight of the backpack.

"No?"

Total disbelief. Incredulity. I felt some of that myself, but I still shook my head. I heard myself saying, "You've got ten minutes. Maybe I think you deserve it. A lot more than Les SaintPierre did."

Brent stayed frozen at first. Then slowly, testing the theory, he got to his feet.

"One thing," I said. "One thing I need an answer about."

He waited.

I drank some more beer before I tried to speak again. Then I met Brent's eyes.

"There's another possible scenario. One I don't want to accept. The scenario where you gave Les those pills intentionally, knowing what they'd do to his alcoholic liver. Les was dead a lot longer than just a day or a few hours—he was dead long enough for you to really put the plan back together. Those septic tanks in the backyard– one of the newer ones had been buried, then dug up again just before the fire. That wasn't just coincidence. It wasn't just holding gray water, either."

Brent waited.

"Tell me that's not the way it was. It wasn't intentional."

Brent shook his head. Then said, almost inaudibly, "It wasn't."

He shouldered his backpack a little more firmly.

He met my eyes.

"I couldn't stand to hear those songs sung," he said. "It was a mistake, letting them out.

If I heard them on the radio, Miranda singing them ..."

He closed his eyes so tight he gave the impression of a man about to pull the trigger next to his temple.

"Catch your plane," I said.

It was hard sounding convinced, sounding like it was really the best thing. It was even harder watching him walk away, but I did. The last I saw was his cowboy hat, just before the Latino kid riding on his dad's shoulders stepped into line and started bouncing up and down along the gateway tunnel, waving his arms out to the side like he was an airplane, obscuring my last view of Brent.

The stewardess smiled and rolled her eyes at the skycap with the empty wheelchair next to her. Kids.

I got up and looked down at the beer Brent had bought me, what was left of it. I dumped it in the bromeliads and walked away.

My phone conversation with Professor Mitchell at UTSA lasted exactly thirty seconds.

He offered me the job. I said I was honoured and I'd have to think about it.

"I understand, son." He tried to make his tone not too obvious—that he didn't understand, that he thought I was an idiot for even hesitating. "When can you let us know?"

I told him next week. I told him I had another kind of class to finish up between now and then. He said fine.

After hanging up, I spent a long time staring at the crepe myrtle out the kitchen window. It was a relief twenty minutes later when Erainya did her customary unsyncopated rattattat on the screendoor frame.

When I opened the door Jem laughed and just about launched a twolayer cake into my chest as he came in. Fortunately I caught the cake while it was still in one piece and raised it up, allowing Jem free rein to tackle me.

Robert Johnson mewed a complaint and disappeared into the closet. He probably remembered the last time the Manoses had come over.

Erainya stepped in and looked around my apartment. "So you're still alive. You don't call why—you forget the number?"

Jem was explaining to me about the cake. He told me that we'd have to wait until I really finished my hours to eat it but he'd made it himself with his food colouring kit and I wouldn't believe the colours inside when I opened it up. The outside was forbidding enough—lumpy gray frosting that looked like the product a cement finger painting session, the layers uneven and offcentre so the cake seemed to be leaning away from me on its plate.

"It's just about the nicest cake I've ever seen, Bubba."

Jem giggled, then went to find the cat.

In the top of the closet a shoe box moved.

Erainya was still waiting for an answer to her question. She was giving me the lookofdeath treatment, her black eyes bugging toward me and her talon fingers tap

ping her forearm.

"I got ten hours left," I told her. "That's about one job. You figure we can avoid arguing that long?"

"It's twenty," she reminded me. "And I don't know, honey. You going to get yourself sidetracked again?"

"Professor Mitchell is probably wondering the same thing."

Erainya frowned. "Mitchell who?"

"I said, yes. I'm willing to finish up. You?"

Erainya thought about it, weighing the pros and cons. "I suppose the Longoria case could've gone better if I'd had a dumblooking guy for a decoy, honey. I supposed there's advantages. Maybe you got a little raw potential. Nothing amazing, you understand. And what about after the twenty hours?'"

Jem came back over with Robert Johnson hanging by his armpits from Jem's hands, Robert Johnson's toes fully extended and the tiny white V on his crotch showing and his face looking like he would die from mortification any second.

Jem looked troubled. "Where's Miranda?"

He'd just made the connection, remembered his trick ortreat partner and remembered that she had some vague association with Tres when she wasn't being Jem's Little Miss Muffett.

Erainya waited to hear an answer to both questions, hers and Jem's. She was chewing on the inside of her mouth, her lips turning sideways.

"Miranda had to go, Bubba. She's going to be a singer in Nashville. Isn't that cool?"

Jem didn't look impressed. Neither did Robert Johnson. Both turned and left. Probably going to play wet kitty/drykitty in bathroom.

"You need anything, honey?" Erainya's voice was softer now, so much so that I had to look to make sure she had really been the one speaking.

She frowned immediately. "What?"

"Nothing. And no. Thanks."

Erainya looked out the window at the afternoon in progress. Gary Hales was in the front yard, watering his sidewalk. Across the street a red Mazda Miata was just pulling up in front of the Suitez house. The Mazda was loaded so heavily with cardboard moving boxes that the trunk was halfopen, precariously fastened with a crisscross of cords. Allison SaintPierre looked across the street, trying to make sure she remembered which house was mine. Last time she was here she'd been drunk.

Erainya and I exchanged looks.

"Nashville, honey?"

"It's not that."

She did a backhand slap in the air. "Ah. I'll wrap the cake in Saran Wrap. Maybe it'll keep."

Knowing how Erainya applied Saran Wrap, I had the feeling the cake would keep several centuries.

I went outside.

Allison saw me coming and sat on the hood of the red Mazda and waited. She was holding a backpack—my backpack, the one I'd left with the maid at her Monte Vista house.

Allison was already warming up her head shake as I walked across Queen Anne Street. By the time I got to her she was going pretty well with it.