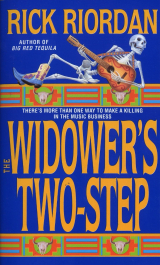

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Sheck's face was dark. He hadn't looked at me while I spoke. He was concentrating on Miranda again, but not with any pleasure. He reached up and dabbed at the edge of the bandages on his cheek. When he finally spoke his tone was forcibly light and completely unnegotiable.

"Don't press your luck no more, son. You hear?"

It wasn't a threat. It sounded as close as Sheck could get to earnest advice. It was also very definitely the end of the conversation.

As I left, Tilden Sheckly's buddies flowed back around the table. They tried their best to reconstruct the joking atmosphere they'd had before—popping new beers, lighting cigarettes, talking in loud voices at my expense. Their boss smiled stonily, looking nowhere in particular, like the majority of his mind had already checked out for the evening.

Robert Earle and Miranda were harmonizing onstage. Couples were slowdancing.

Milo was entertaining the Nashville bigwigs with funny stories and a new round of wine coolers.

I nodded amiably to the Bexar County deputy on my way inside. My birthday Budweiser was empty. One down, twentynine more to go.

47

At the break I stood outside the entrance of the bar, watching the occasional headlights go down the road. Tilden Sheckly and his friends had left long ago. About fifty other people had arrived, many of them excited when the tickettaker told them Miranda Daniels was in the house. Nobody got particularly excited to see me at the door. Nobody asked for an autograph.

A few minutes after the canned music began, Miranda appeared at the entrance, followed by a cadre of smiling cowboys. She thanked them and begged off drink offers until they finally drifted away. Then she came over to me, smiled, and circled her arm through mine.

Without speaking we started down the hill toward the Helotes Creek Bridge. After a hundred yards, the night closed around us. The sky was still overcast but in the south the reflection of city lights made a dull shine. We stopped at the bridge.

Miranda went to the metal railing and leaned against it. I joined her. We were about eye level with the tops of the stunted mesquite trees that filled up the dry creek bed below. You couldn't see much, but you could smell the wild mint and anise, steamed into the air by the warm day.

"Milo said it sounded good," Miranda mused.

"It sounded great."

Miranda didn't have to lean too far to press against me. "He doesn't approve of you, does he?"

"Robert Earle Keen?"

She bumped against me, playfully. "Milo. I thought he was your friend."

"He's worried about your record deal. You've got a lot on the line and Milo's afraid Sheckly's going to ruin your chances. He's unhappy I haven't found a way to get Sheckly to lay off yet."

She ran her hand along the metal rail until it met mine. "That's not all, is it?"

"No. Last time Milo and I worked together—there was a woman. It took three or four years before we could speak to each other again after that. He's probably afraid I'm getting distracted again, with somebody he's got a stake in."

"Are you?" There was a warm, husky undercurrent in her voice.

I stared into the mesquites. "We should probably talk about that. We should probably talk about why you decided it would be useful."

It was impossible to see her face in the darkness. I had to read her momentary silence, the sudden absence of her hand and her side against mine.

"What?" she asked.

"You said it Friday night—it looks like you're along for the ride. Everybody worries about taking care of you because they're sure everyone else is going to mess up the job. You cultivate that kind of dependency pretty well– it's gotten you a long way."

"I don't ..." Her voice faltered. It sounded compressed, still slightly playful, like she had crossed over the line in a teasing game and was just starting to realize the person yelling "stop" really meant it. "I'm not sure I like the way you're talking, Mr. Navarre."

"The funny thing is I don't blame you," I said. "I want to see you make it. You've had a pretty shitty family life up to now—you did what you could to get yourself somewhere.

You figured out ways to keep your dad in check. You got Sheckly to be your standard

bearer. You got your brother to sell out his songs to you. When Sheck's patronage became too confining you got Cam Compton to give you information that could shake you free, then you encouraged Les SaintPierre to try a little blackmail scheme. When things started getting scary you figured it might be useful to have me around your finger, so you gave me Friday night. Now you're getting unsure about your chances with Century Records so you're hedging your bets with Sheck again. We're all stuck on you, Miranda. Milo. Sheck. Me. Even Allison. We're all running around tackling each other and treating you like a football, and here you are quietly calling all the moves.

Congratulations."

"I don't believe you just said that."

I ran my hands along the metal rail. "Tell me I'm wrong, then."

Far down the hill, a new song started up from Floore's backyard. I could decipher the bass guitar, an occasional fiddle line above it.

Miranda said, "You think that I was with you Friday night just because—" She let her voice twist, fall silent. Everything in me said I should respond, offer an immediate retraction.

I resisted.

A breeze lifted up from the creek bed. It brought a fresh wave of hot anise smell with it.

"I won't let you think that," she insisted.

She folded herself against my chest and pushed her arms under mine, wrapping fingers around my shoulder blades.

"That's not a denial," I said.

She turned her face into my neck and sighed. I kept holding her, lightly. There were little specks of sand in my throat.

I'm not sure how long it was before the Danielses' white and brown pickup truck drove by us on the bridge. It slid down Old Bandera almost soundlessly, riding the brakes all the way, and doubleparked sideways in front of Floore's.

I made my voice work. "Were you expecting your brother?"

Miranda pulled away, letting her hands slide down until they hooked into mine. She looked where I was looking, saw her father fifty yards away, getting out of the passenger's side of the old Ford. The man coming around the front through the Ford's headlights wasn't Brent—it was Ben French, the drummer. The two men walked together into the bar.

A premonition started twisting into a solid weight somewhere inside my rib cage.

Miranda said, "Why—"

She turned and started walking back toward the bar, trailing me behind her.

Willis and Ben and Milo Chavez met us at the corner of Old Bandera, under the streetlight.

Daniels looked haggard and old, not just with drinking, although he'd obviously been doing that, but with anger and a kind of washedout emptiness, the dazed way people look when they're coming off a crest of grief and waiting for the next surge to hit. He leaned on his cane like he was trying to drive it into the ground. Ben French looked equally haggard. Milo's face was dark and angry.

As we took a few final steps to meet them, Miranda's hand tightened on mine.

"I thought you were in Gruene tonight," she asked her father.

"Miranda—" His voice cracked.

"Why are you driving the truck?" she demanded.

Willis stared at Miranda's hand in mine, confused, like he was mentally trying to separate whose fingers were whose.

"Navarre," Milo put in. He nodded his head back toward the bar, willing me to come with him, to leave father and daughter alone.

Miranda's hand stayed fastened on mine.

"What's happened?" Her voice was sterner than I'd ever heard it, impatient.

"There's been a fire at the ranch," Willis managed to say.

"A fire," Miranda repeated. It was a whisper.

Milo kept looking at me, willing me to step away.

"Where's Brent?" Miranda demanded. But her voice was thin now, glassy.

When no one answered at the count of five, Miranda tried to ask her question again, but this time her voice cracked into small shards of sound.

Willis Daniels looked down at his cane, saw that he hadn't yet driven it into the ground, and wiped his nose with tired resignation.

"You'd best drive with your friends," Willis suggested.

Then he turned to go back to the truck, Ben French holding his arm.

48

The old tractor shed had cracked open like a black eggshell, ^r You could still see huge scars the fire engine had made coming through the gravel and mud, the barbedwire fence it had plowed through in order to get around the back of the house.

All that was left now were three Avalon County units in the front yard, their roof lights rotating lazily, cutting red arcs across the branches of the granddaddy live oak. The medical examiner's car was pulled around the side of the house, parked diagonally over the horseshoe pit.

Around the back of the house a generator whined, cranking out juice for the floodlights that illuminated the sooty wreckage of Brent's apartment. The smell of wet ashes was cloying even from twenty feet away.

Miranda and her father stood on the back porch, talking to a plainclothes detective.

Miranda's face was bleached and vacant. Every few seconds she would shake her head for no apparent reason. Her orange and white blouse had poofed out from her skirt on the left side and wrinkled like a balloon frozen on dry ice.

I looked over what was left of Brent Daniels' front wall. Inside, the hoseddown ashes made a thick, glistening surface, almost a bowl shape. Sticking out of the sludge were lumps, objects—pieces of wood that had miraculously remained unburned right next to large pools of melted metal.

The south wall, to my right, was still almost full height. Most of the wood had bubbled and blackened, but one upper cabinet had come open postfire, revealing a perfectly intact set of dishes. The paint on the inside of the cabinet was pink. The photo of Brent Daniels' mother had been preserved.

Fires have a rotten sense of humour.

Jay Griffin, the medical examiner for Avalon County, had staked out an area where Brent's cot had been, the place where I'd slept that afternoon. Jay and two other men with white gloves were poking into the ashes with what looked like plastic rulers.

Milo walked back to me from the toolshed, where he'd been interrogating one of the deputies. "You overheard?"

I nodded. I'd overheard. Barred door, from the outside. Clear traces of incendiaries on the outer walls, pooled inside where the windows had been. One victim lying on the cot—perhaps drugged, perhaps already dead. No struggle to get out, anyway. The M.E. had mostly charred bones to work with. Maybe some dental work. It takes a lot to burn a human body. Somebody had gone the extra mile.

I looked out into the fields, unnaturally lit up by the spotlights. It made me feel like I was back in a high school stadium night game, all the shadows long and elastic. Third and ten.

The chickens in the coop were little red feathery lumps—dead from the heat. The woven straps on the lawn chairs sagged in the middle where they'd melted.

Farther out, two rusted, dirtcaked septic tanks leaned against the shed. The new tanks had apparently been sunk into the proper places, ready to store gray water for the garden, to make sure the ranch's toilets flushed properly. I'm sure that would've been a big comfort to Brent Daniels, the man who wrote most of Miranda's soonto be hit songs, knowing he'd spent his last afternoon filling in sewage lines.

"Ten gets you twenty," Milo said, "it'll go down as an accident. A suicide, maybe."

On the porch, Willis Daniels was nodding vaguely, grimly, to something the detective was telling him. Miranda had her fingers curled tight against her palms and was pressing them against her eyes.

"They couldn't," I said.

I had already filled Milo in on my latest findings. He had expressed no surprise at the information Sam Barrera had given me, no surprise that the authorities wouldn't be riding to the rescue in time to save his record deal, only a sour regret that Les hadn't gone through with his blackmail plan. I had not told him about my conversation with Miranda.

Milo turned over a charred board with his foot, so the unblackened side of the wood faced up. "One damn signature. All that leverage and all we need is a goddamn signature—not even an admission that Sheck's contract was forged. Just a waiver.

We've got to do something ourselves, Navarre. Friday—"

"You're still thinking about your deadline. After this."

"Come on, Navarre. If Century hears—"

I kicked the board away. It skittered through the wet grass.

"Probably good publicity. Be happy, Milo. You won't have to pay Brent his twentyfive percent for the song rights."

"God damn it, Navarre—"

But I was already walking away. It was either that or take a swing at Milo, and I wasn't the right combination of angry and drunk and stupid for that. Not yet.

I didn't look where I was going.

I pushed through a couple of newspaper reporters who were trying to interview a deputy lieutenant, then halfway to the porch I ran into a burly plainclothes officer who was helping the evidence technician raise a camera tripod.

Before I could apologize Deputy Frank turned around and told me to watch it.

Whatever other angry comments Frank might've been about to make, he swallowed them back like live coals when he recognized me.

"You going to get that, Frank?" the evidence tech said behind him.

Frank looked me in the eye. What I saw in his face was too much information, too many questions that all blurred into something incomprehensible. White noise. His expression was the visual equivalent of picking up a receiver and listening to the shriek and hiss of a modem.

He looked away. "Yeah. Sure."

Then he turned and helped the evidence tech lift the tripod.

I walked up the steps to the back porch.

Willis had just asked a quiet question and the county detective was responding in an equally quiet, gentle voice. The detective had a slick curve of black hair combed almost into his eyes, like a crow's wing glued to his forehead.

"We don't know," he said. "We probably won't—not for a while anyway. I'm sorry."

Willis began to say something, then thought better of it. He glared at the bluepainted floorboards. He looked twenty pounds thinner—most of it taken from his face. The skin around his eyes was unnaturally gray, the wrinkles that ran from the edges of his nose into his moustache and beard so deep his face looked carved.

When he saw me his grief turned into something heavier, something more active.

I walked over to where Miranda sat on the porch railing. She was hugging her arms.

Her carefully curled hair had disintegrated into simple tangles again and her gigperfect makeup job was completely scoured away.

I didn't ask how she was doing.

She only acknowledged my presence by a change in her breathing—a shaky inhale, then a long exhale. She tried to untense her shoulders. Her eyes shut.

The detective was asking Willis a few more questions– When had he left for Gruene Hall that evening? Was he sure Brent had planned on staying home all night? Had Brent had any unusual visitors lately? Had Brent been seeing anyone special? Or broken off any relationships?

At the last question Miranda opened her eyes and glanced over at me. The composure she'd been knitting together over the last hour started to unravel.

Willis wasn't listening to the detective's questions. He was watching me, and the way Miranda was crying. I tried hard not to feel the way the old man's eyes were attaching themselves to my face.

"Do you want to leave?" I asked Miranda quietly, then to the detective, "Can we leave?"

The detective frowned. He lifted the crow's wing off his forehead, then let it fall back into place. He said he supposed there wasn't any problem with us going.

Slowly, Miranda collected enough energy to stand. She steadied herself against the porch beam.

"All right," she whispered. "I can't—"

She looked at the blackened tractor shed, the spotlights. She seemed unable to complete the thought.

"I know," I told her. "Let's go."

"The hell you will."

Willis Daniels' words took even the homicide detective by surprise. It wasn't so much the volume as the acid tone, the suddenness with which the old man stepped toward me.

" You killed him, you son of a bitch." He pointed his cane at my feet and made ready to smash my toes. "It was something you did, wasn't it? Some trouble you stirred up."

Miranda moved a few inches behind me. There was no hesitation, no faltering in the way she did it. It was obviously a manoeuvre that had long ago become instinctive for her.

The detective looked back and forth between us, interested. "You want to explain?"

Willis glared at my feet.

The detective looked at me.

I gave him an explanation. I told him some of the things that had been happening to Miranda since Century Records became interested in her. I told him I'd been hired to find out what I could and that as far as I knew Brent Daniels would've had absolutely no reason to be in the line of fire. I gave the detective my name and number and address and said sure, I'd be happy to talk more.

"But right now," I said, "I'm getting Miranda out of here."

The detective looked at Miranda, then looked at me. His eyes softened just a little. He said all right.

"This is her home," Willis growled.

I found myself stepping toward the old man, grabbing the tip of the cane that he'd raised toward me. The tension along the shaft of wood was uneven, his grip on the other end weak. With not much force I could've taken it away, or thrust it back.

Anything I wanted.

"Tres—" Miranda said.

Her fingers dug into my shoulders with a surprising amount of force.

I pushed the tip of the cane away, lightly.

"Call me whenever," I told the detective.

The detective was reappraising me moment by moment, like I was a tie game in progress. Sudden death overtime.

"I'll do that," he promised.

Miranda's fingers relaxed.

As I walked back down the steps, holding Miranda's hand, Milo Chavez was arguing with one of the newspaper reporters—something about family privacy. I couldn't tell if he was arguing for or against. Deputy Frank was still looking at me, giving me white noise with

his eyes. Jay Griffin the M.E. had lifted something long and black and thin from the ashes of the tractor shed and was turning it. In the spotlights the forearm looked sur

real, like a piece of black glazed ceramic, nothing that could ever have been part of a human body.

49

The next morning vendors were selling offerings for the dead all along General McMullen Road. The parking lot of the orange stucco strip mall was lined with battered pickup trucks and delivery vans, all covered with wreaths, crosses made of blue silk flowers, pictures of Jesus, flowery frames empty and ready for the insertion of the beloved's pictures. There were tables of foodstuffs—pan muerte, the bread of the dead, fresh tamales, tortillas, black catand pumpkinand skullshaped cookies.

Dia de los Muertos was tomorrow. Today—All Souls' Day—was just a warmup.

Otherwise we would never have been able to turn into San Fernando Cemetery without getting choked in traffic.

The circular maze of oneway drives wasn't empty by a long shot, though. In every section of the cemetery people were unloading the trunks of their cars—coffee cans of marigolds, picnic baskets, all the things their antepasados would need. Old men with trowels were cutting weeds away from the marble plaques, or digging holes for new plants. About half the graves had already been adorned, several buried so thick in flowers they looked like a florist's waste dump.

The less conventional graves had fake cobwebs covering them, flowers planted in jacko'lanterns, little cloth ghosts dangling from strings on the tombstones. Others were fluttering with ribbons and spinning sunflower and flamingoshaped pinwheels.

"Good Lord," Miranda said.

She was dressed in jeans and her boots and an oversized U.C. Berkeley Tshirt she'd borrowed from my closet. Her hair was pulled back in a clasp. Her face, cleanscrubbed and devoid of makeup, looked pale and younger. She wasn't back to normal by a long shot– about every hour her hands would start trembling again, or she'd suddenly start crying, but there were pauses when she seemed surprisingly stable. She'd even given me a weak smile when I'd brought her huevos rancheros for breakfastinfuton. Or maybe what made her smile was the way I looked in the morning after sleeping on the floor with the cat all night. She wouldn't tell me.

We drove around a huge mound of rocks topped with a lifesized stone crucifix. At the base of Jesus' feet a brown mutt dog was taking a nap. We kept driving toward the back of the cemetery, then circled around.

I was looking for a maroon Cadillac.

I finally found it in the centre of the cemetery.

Ralph Arguello was about twenty yards from the curb, standing over his mother, a large woman in a brown sack dress who was kneeling at one of the graves, planting marigolds. Ralph was easy to spot. He was dressed in his outfit of choice—oversized guayabera shirt, jeans, black boots. His black ponytail looked freshly braided. The butt of his .357 had snagged on the edge of the olive shirt, making it anything but concealed. He was holding a bunch of silver Mylar balloons decorated with pictures of trains and cars.

I parked behind the Cadillac. Miranda followed my stare.

"That's your friend?"

"Come on."

We walked between grave markers—most of them flat plaques, mirrored gray granite that reflected the sky perfectly. The mottoes on the tombstones were trilingual– Latin and Spanish and English. The decorations were something totally different—somewhere between ancient Aztec and modern WalMart.

Ralph turned toward us as we walked up. His thick round glasses looked cut from the same material as the Mylar balloons and the tombstones.

It was difficult to tell whether he looked at Miranda or not.

" Vato," he said.

I nodded.

We waited for a while, not saying anything else while Mama Arguello completed saying the rosary over the grave.

At first I didn't realize where we were, what part of the cemetery.

Then I noticed how close together the grave markers were, that each space was no more than two feet wide. They went on like that, row after row, for what looked like a good half acre. Nearby was another marble Jesus, this one surrounded by kids. The Spanish inscription: Suffer the Children.

The decorations around us were sprinkled with Halloween candy, toys, flower arrangements shaped like lambs. Mama Arguello finished her prayers and then took the cluster of balloons from Ralph and tied it on a stake in the grass. The engraving on the marker said: "Jose Domingo Arguello, b. Aug. 8, 1960, d. Aug. 8, 1960. In recuerdo."

The hook on the stake had frayed knots from past years of balloons—all babyblue ribbons, some perhaps decades old.

Mama Arguello smiled and gave me a hug. She smelled of marigolds—a pungent scent like perfume from a jewellery box buried for a hundred years. Then Mama Arguello hugged Miranda, telling her in Spanish that she was glad we could come.

It didn't really matter that Mama Arguello didn't know Miranda. Mama A. had stopped caring about things like that about the time she stopped being able to see. Her glasses, Ralph assured me, were just for show. With or without them, the world for Mama had long ago become a series of blurry spots and lights. It was now mostly about smells and sounds.

"Come with me," she told Miranda. She dug her pudgy brown fingers into Miranda's forearm. "I have some tea."

Miranda looked uncertainly back at me, then at Ralph. Ralph's grin couldn't have made her feel any easier. The old woman led her back to the Cadillac, where she started unloading things into Miranda's arms—a thermos, a picnic basket, two pots of flowers, a large wreath.

Ralph made a small laugh. When he looked down at the tomb marker his smile didn't waver at all.

"My older brother," Ralph told me.

I nodded. Jose Domingo. An old man's name.

I wondered how many hours Jose had lived, what he thought up there in heaven of the thirtyplus years of infant's gifts and balloons he'd been receiving at his grave site.

"You got more family here?" I asked Ralph.

Ralph waved his hand toward the east, like it was his real estate.

"Take us two days, me and Mama. Start here and work our way around. Yvette's right over there. We have lunch with her, man."

Yvette. Kelly Arguello's mother. I exchanged looks with Ralph, but he didn't have to tell me about Kelly not being here, or about what he thought of her defection.

He watched Miranda struggling with the ofrendas Mama Arguello kept handing her.

Mama was giving her directions in Spanish, telling Miranda stories she couldn't understand.

Miranda began smiling. At first it was strained, grieved. Then Mama told her about who a particular bottle of whiskey was for, a real cabron, and Miranda laughed despite herself, almost spilling a plate of cookies balanced in the crook of her arm.

"The chica's in trouble?" Ralph asked.

"I don't know. I think she might be."

I told him what had been happening. Ralph shook his head. "Pinche rednecks. Pinche Chavez. You don't see him out here today."

"Can you help, Ralphas?"

Ralph looked at his brother's tombstone, then reached down and yanked out a piece of crabgrass at the edge of the marble. He threw it behind him carelessly. The weed landed on one of the unadorned graves, behind him. "This lady mean something to you?"

I hesitated, tried to form an answer, but Ralph held up his hand.

"Forget I asked, vato. How long I known you, eh?"

From another person, it would've irritated me. From Ralph, the statement was so honest, the grin that went with it so blatantly amused, that I couldn't help but crack a smile. "A long time."

"Shit, yet."

Miranda came back, burdened down with gifts for the dead but more at ease now, smiling tentatively. She followed Mama Arguello as she led the way to the next ancestor. Miranda looked back at me and asked, "Coming?"

We went to visit Yvette, about half an acre away. Her tombstone was an upright piece of white marble, rough finished around the edges. The stone was almost engulfed in a large pyracantha bush that hung its branches down in the shape of an octopus. Each branch was thick with red berries the size of bird shot.

Across the drive from her grave, a new hole was being dug. The riderless backhoe had scooped out a perfect coffinsized trench in the lawn and was now standing there, abandoned.

I stared at the backhoe.

Miranda helped Mama Arguello spread a blanket next to the grave and set out some paper plates of cinnamon toast and cups of steaming tea that smelled like lemon.

The cold air swept the steam from the tea. Mama set out a plate and a cup for Yvette's grave, then began telling the tombstone how well Kelly was doing in college. Ralph listened without comment. Miranda was shaking her head, looking across the cemetery at similar scenes here and there, at different grave sites. There were tears on her cheeks again.

"Today is better," Ralph told her. "Tomorrow—loco.

Worse than Fiesta."

Miranda brushed her hand under her eye, dazed. "I've lived in San Antonio my whole life—I never—" She

shook her head.

Ralph nodded. "Which San Antonio, eh?" A few feet away, a family unloaded from a long black town car. The grandmother had wraparound sunglasses and walked stiffly, like this was her first time out of the nursing home in a long time. She was escorted by a woman with orangeandbrownstreaked hair and a pink sweat suit and lots of jewellery. A couple of teenage girls followed, each with an expensive warmup suit and a smaller version of mom's hairdo and jewellery ensemble.

They walked to a grave where the colours were white and green, the wreath a flowery Oakland A's logo. On the tombstone was a flowerframed picture—a teenage boy in an open coffin, his face the same colour as the white satin, his A's jersey on, his hair combed and his pencil moustache trimmed and a look of pride sculpted on his dead face. Gangbanger. Maybe fifteen.

"Ralph has a rental house nearby," I said. "I've used it before."

Miranda looked beyond the cemetery, into the surrounding neighbourhood of rundown stores and multicoloured oneroom houses. The tears were still coming.

"Is it safe?"

Ralph started laughing quietly.

"Nobody you know would ever look here," I said. "That's the whole point. You stay with Ralph, you'll be safe."

Miranda thought about that, then looked at Mama Arguello, who was offering her some lemon tea.

"All right," Miranda said. And then, like her timer had run out, she curled her head against her knees and shivered.

Mama Arguello smiled, not at all like she knew what we were talking about, then she told Yvette's tombstone how nice it was to have visitors, how fresh the pan muerte tasted this year.