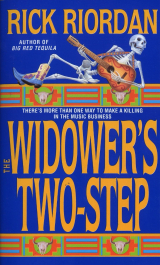

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

41

Sam readjusted his belly above his belt line. He turned his chair sideways and stared out the window.

"The scenario you described is commonplace. Frequently someone at a venue records the shows. Frequently the recordings turn up as bootlegs."

He waited to see if I was satisfied, if I would give in now. I just smiled.

Sam's jaw tightened. "What is uncommon with the Indian Paintbrush situation is the scale. Mr. Sheckly is presently recording something like fifty name artists a year. The master tapes are sent through Germany to CD plants, mostly in Romania and the Czech Republic, then distributed to something like fifteen countries. More recently, as you said, his partners in Europe have been encouraging Mr. Sheckly to target the U.S. market, moving him from boots to pirates."

"What's the difference?"

" Boots are auxiliary recordings, Navarre—studio practice sessions, live recordings, cuts you couldn't get in the store normally. Sheckly's radio shows, for instance. Pirates are different—they're exact copies of legitimate releases. Boots can make money, but pirate copies undercut the regular market, take the place of legitimate work. They have massive potential. You make them well, you can even pass them off to major suppliers—department stores, mall chains, you name it."

"And Sheckly's are good?"

Barrera opened his desk drawer and got out a CD. He took the disc from the case and pointed with his pinkie at the silver numbers etched around the hole. "This is one of Sheckly's pirate copies. The lot numbers on the SIDs are almost correct. Even if the Customs officials knew what they were looking for, which they rarely do, they might pass this. The covers, once they're added, are fourcolor printing, quality paper stock.

Even on the boots Sheck's taken precautions. The liner notes are stamped 'manufactured in the E.U.' This is meant to make one think it's a legit import, explain the difference in packaging."

"How profitable?"

Barrera tapped a finger on the desk. "Let me put it this way. It's rare that you have one syndicate controlling the manufacture and distribution of so many recordings in so many countries. The only similar case I know of, the IFPI confiscated the receipts of an Italian operation. For one quarter, one artist's work, the pirates pulled in five million dollars. It'd be less for country music, but still– Multiply the number of artists, four quarters a year, you get the idea."

"Business worth killing for," I said. "What's the IFPI?"

"International Federation of Phonographic Industries. European version of the RIAA in the States."

"Your client."

Barrera hesitated. "I never said that. You understand?"

"Perfectly. Tell me about Sheckly's German friends."

"Luxembourg."

"Pardon?"

"The syndicate is based in Luxembourg. Just so happens Sheckly made his connections in Bonn, does most of his business in Germany."

I shook my head. "Help me out, Barrera. Luxembourg is the little country?"

"The little country known for laundering mob money, yes. The little country known for maintaining loopholes in the E.U.'s copyright laws. The pirates love Luxembourg."

I sat for a while and tried to process it. I was determined not to feel out of my league, not to show Barrera I was going to run from the room screaming if he gave me one more acronym.

"Sheckly got himself into a dangerous association," I said.

Barrera came the closest I'd ever seen to a laugh. It was a small noise in the back of his nose, easily mistaken for a sniff. Nothing else in his face moved.

"Don't start shedding tears, Navarre. Mr. Sheckly's pulling down a few million extra a year."

" But Blanceagle's murder, and Julie Kearnes'—"

"Sheckly may not have ordered them but I doubt he had much of a conscience attack.

It's true, Navarre, bootlegging is usually whitecollar stuff, not very violent. But we're talking a large syndicate, into gunrunning and credit cards numbers and several other things."

"And Jean?"

"Jean Kraus. He's beaten murder raps in three countries. One victim was a young French boy, about thirteen, son of Jean's girlfriend. He decided to lift some of Jean's petty cash. They found the kid in an alley in Rouen, thrown out a fifthstory hotel window."

"Jesus."

Barrera nodded. "Kraus is smart. Probably too smart to get caught. He's over here encouraging Sheck's CD distribution network in the U.S. It's only a matter of time before Jean and his bosses start using Sheckly's trucking lines for their other interests—guns, especially. That's finally what got the D.A. and the Bureau and ATF interested. It takes a lot of firestoking to get them excited about stolen music."

"Your big league friends."

"We've got a case for mail fraud in four states, interstate commerce violations—orders placed and filled with some of Sheckly's distributors. Even that has taken years to assemble, to get a judge interested enough to grant access to Sheckly's bank statements and phone records. Throw in the fact that Avalon County law enforcement is in Sheckly's pocket—it's been tough going. Ninety percent of a case like this has to be informants inside."

"Les SaintPierre. He made himself your solution."

"What?"

"Something his wife said. He was your in."

"To Julie Kearnes, yes. And Alex Blanceagle. And all three of them disappeared as soon as they started talking. We may lose the interest of the State Attorney's Office if we don't get more soon, something solid. Now it's your turn. What was in the boat?"

I took out the addresses I'd found in the ice chest– locations with dates next to them.

I handed them to Barrera.

Barrera frowned at the paper. When he was done reading he looked out the window again and his shoulders drooped. "All right."

"They're distribution points, aren't they? Dates when shipments of CDs will arrive."

Barrera nodded without much enthusiasm.

"You've got locations," I prompted. "You know what Sheckly is doing. You can stage a raid."

Barrera said, "We have nothing, Navarre. We have no grounds for requesting a search warrant—no evidence linking anyone to anything, just some random addresses and dates. Maybe eventually, that information will lead us somewhere. Not immediately. I was hoping for more."

"You've been building the case for what—six years?" I asked.

Barrera nodded.

"Chances are Sheckly knows," I said, "or he's going to know soon that this information is compromised. You don't move on it now, they'll move the goods, change their routes. You'll lose them."

"I'll go another six years rather than get the case thrown out of court because we acted stupid. Thanks for the information."

We sat quietly, listening to the A & M Fighting Aggie clock tick on Barrera's back wall.

"One more thing," I said. "I think Les fled to the Danielses. Or at least he considered it."

I told Barrera about the phone call from the lake cabin.

"He would be stupid to go there," Sam said.

"Maybe. But if I got the idea Les might've enlisted their help, Sheckly's friends could get the same idea. I don't like that possibility."

"I'll have someone go out and talk to the family."

"I'm not sure that will help the Danielses much."

"There's nothing else I can do, Navarre. Even under the best of circumstances, it will be several more months before we can coordinate any kind of action against Mr.

Sheckly."

"And if more people die between now and then?"

Barrera tapped on the desk again. "The chances of the Daniels family getting targeted are very slim. Sheckly has bigger problems, bigger people to worry about."

"Bigger people," I repeated. "Like thirteenyearold boys who steal Jean Kraus' petty cash."

Barrera exhaled. His chair creaked as he stood up. "I'm going to say what I said before, Navarre. You're into something over your head and you need to get out. You don't have to take my word for it. I've levelled with you. Is this something an unlicensed kid with a couple of years on the street can handle?"

I looked again at the photo of Barrera and my father. My father, as in all his photos, seemed to grin out at me as if there was a huge private joke he wasn't sharing, almost certainly something that was humorous at my expense.

"Okay," I said.

"Okay you're off the case?"

"Okay you've given me a lot to think about."

Barrera shook his head. "That's not good enough."

"You want me to lie to you, Sam? You want to go ahead and arrest me? Avalon County would approve of that approach."

Barrera sniffed, moved over to his window, and looked out over the city of San Antonio. It was deadly still on a Sunday morning—a rumpled gray and green blanket dotted with white boxes, laced with highways, the rolling ranch land beyond a dark bluegreen out to the horizon.

"You're too much like your father," Barrera said.

I was about to respond, but something in the way Barrera was standing warned me not to. He was contemplating the correct thing to do. He would have to turn around soon and deal with me, decide which agency he needed to turn me over to for dissection. He would have to do that as long as I was a problem, sitting in his office, telling him what was unacceptable to hear.

I removed the problem. I stood up and left him standing by the window. I closed the office door very quietly on my way out.

42

The day heated up quickly, By eleven, when I exited the highway for WJ Ranch Road 22 in Bulverde, the clouds had burned away and the hills were starting to shimmer. I took the turn for Serra Road, then drove over the cattle guard and pulled my VW under the giant live oak in front of the Danielses' ranch house.

No one answered the front door so I walked around by the horseshoe pit.

The back field looked like a playground for the Army Corps of Engineers—pyramids of PVC and copper pipes, crisscrossed trenches, mounds of caliche soil. The other night it had been too dark to see the extent of the work.

Leaning against a utility shed out beyond the chicken coop were three metal canisters a little smaller than cars—septic tanks. Two were dull silver and pitted with rust holes.

The third was new and white but caked here and there with clods of dirt, as if it had been improperly installed and then dug up again.

The riderless backhoe squatted at the end of a trench, its shovel nuzzling the caliche.

The backhoe was speckled with dirt and machine oil but looked fairly new, painted the green and yellow of a rental company.

I heard a tape playing out beyond the tractor shed. It was spare acoustic guitar and male vocal—like early Willie Nelson.

I walked that direction. The horse in the neighbouring field watched me with her neck leaning into the top of the barbed wire while she chewed on an apple half.

When I got closer I realized the tape I was hearing was one of the songs Miranda performed, only changed for a male singer. When I got around the other side of the shed I realized I wasn't hearing a tape at all. It was Brent Daniels singing.

He was sitting in one of two lawn chairs against the far wall of his tractorshed apartment, next to the chicken coop. He was facing the hills and strumming his Martin for the hens.

His hair was tousled into a thin wet black mess, like he'd just showered. He wore a Tshirt and denim shorts.

There was a stack of Dixie cups and a bottle of Ryman whiskey on the tree stump next to him. He'd made a bold start on the bottle. He was singing his heart out and for the first time I realized just how good he really was.

He didn't hear me coming up, or he didn't care. I stayed about twenty yards away and listened to him finish the song. He gave the impression that he was singing to somebody on the hilltop over on the horizon.

When Brent finished he let the guitar slide off his lap, then he picked up the whiskey bottle and poured himself a cupful. He slugged it down and glanced at me.

"Navarre."

"I thought you were a recording."

Daniels frowned. " You want Miranda, she's in Austin, mixing the demo. Willis is out getting more finger pipes."

"In that case, mind if I join you?"

He deliberated, like he wanted to say no but was so out of practice turning down social requests that he didn't remember how. He held the stack of Dixie cups toward me. I took one off the top, then sat in the other lawn chair.

You could see a long way off. The hills in the distance were green. The sky was blue the way amusement park water is blue—an unnatural, dyedforthetourists kind of look, with foamy little scraps of cloud. A couple of turkey buzzards circled about half a mile to the north, over a clump of trees. Dead cow or deer, probably. To the east there was a brown zigzag of haze from someone's brushfire.

The Ryman whiskey burned its way down my throat.

"Les' brand, isn't it?"

Brent shrugged. "He gives it out. Door prizes."

I wanted to ask some questions but the country air, the country mood, had started working on me. I realized how tired I was, how tired I'd been for the past few weeks.

The midday sun was warm but not unpleasant, just enough to burn the last of the dew off the chicken wire and get some warmth into my bones. The hills invited quiet spectating. The reasons I had come out to the ranch house started unknitting in my head.

"You play out here often?"

Some shadows deepened around Brent's eyes. "I suppose."

"Y'all got another gig tonight?"

He shook his head. "Just Miranda. She's got a show up scheduled with Robert Earle Keen at Floore's Country Store. I suppose Milo's going to bring her back down for that."

I dabbed the flakes of Dixie cup wax off the surface of the liquor. "Miranda doesn't drive at all, does she?"

I hadn't even considered that fact until I said it. I hadn't questioned it Friday night, when I'd given her a lift into town, or the other times when she'd gotten rides with Milo or her father. The fact that I had just naturally accepted it, not even thought about it as odd, disturbed me for some reason I couldn't quite put into words.

"Not that she can't," Brent said. "She doesn't."

"Why?"

Brent glanced at me briefly, declined comment.

He picked up his guitar again and picked the strings so lightly I almost couldn't hear the notes. His hand changed chords fast, contorting into various claw shapes on the fret board.

"You ever get frustrated with her playing your songs?" I asked. "Getting all the attention for your music?"

Brent kept playing quietly, looking at the hills as he worked his fret board, occasionally twitching his eye as he reached for a harder note. His face and his hands reminded me of a deepsea fisherman's as he worked his rod and reel.

"She was grateful at first," he said. "Told me she couldn't have done it without me—that she owed me everything. She gives you those bright eyes—" He smiled, a kind of sad amusement. Suddenly he looked like his father, a leaner version, less gray, weathered a little sooner and a little more harshly, but still Willis' son. "Guess you're the cavalry now, ain't you, Navarre?"

"You never thought much of Milo hiring a private eye."

"Nothin' personal," he said. "Seems to me Les has ditched us, Milo's trying to prove he's got things under control. It's not—I appreciate—" He stopped himself, not sure how to proceed. "Miranda was talking about you yesterday. She seemed to feel a lot easier about things—said you were a good man. I do appreciate that."

He meant it, but there was an uneasiness in his tone I couldn't quite nail down.

"Something about her Century Records deal is bothering you."

He shook his head uncertainly.

"Has Les tried to call you?"

Brent frowned. "Why would he?"

"Just a thought. You don't figure he would've contacted Miranda?"

"Les is gone for good. That's pretty obvious, ain't it?"

"Is that what Allison's hoping?"

Brent played a few more chords. His focus moved farther away by a few hundred miles. "It never should have happened between me and her."

"None of my business."

Brent shook his head sadly.

For no reason I could see he decided to start singing again. It was a pretty tune—one of his slow ones, "The Widower's TwoStep."

Coming straight from Brent the song was a hundred times sadder. I could almost feel the weight of the tractor shed apartment on his back, imagine a young woman in there, pregnant, dying from some condition I couldn't even remember the name of.

I got myself another Dixie cup full of whiskey. The liquor made a warm heavy coating around my lungs.

When Brent finished the last verse we were quiet for a long time. The sun was nice.

The circling buzzards and the horse pawing up the field and even the frantic, coked up movements of the chickens were all getting more and more fascinating the more I drank. I could've settled into that lawn chair for the rest of my life, I figured.

"You get any money from the songs?" I asked. "Allison was saying something—"

Brent nodded. "Quarter royalties."

"A quarter?"

"Half to the publisher."

"And the other quarter?"

"Goes to Miranda as cowriter."

"She cowrote the songs?"

"No. But it's standard," Brent said. "The artist who records the song gets half credit for writing it even if they didn't. Looks better on the album that way. It's a tradeoff for them choosing your material."

"Even if she's your sister?"

"Les said it's standard."

I watched the turkey buzzards. "Seems like Miranda could've made it unstandard."

He shrugged. I couldn't tell whether he cared or not. I wondered what conversations Allison had had with him about that.

"Les ever stay at the ranch house?" I asked.

He nodded reluctantly. "Once. I was following him back from a gig one night, he run himself off the road from all the drink and pills. Had to convince him to come back here and sleep it off. He wasn't a happy fella. He talked a lot about selfdestructing that night."

"How'd you handle it?"

Brent played a chord. "Told him I'd been there."

He sang another song. I drank more. My feet were pleasantly numb and I was enjoying the sound of Brent Daniels' voice. I felt easy and comfortable for the first time in days.

Not thinking about whether I wanted to become a licensed P.I. or a college teacher or a neon blue bearded lady for Cirque du Soleil.

Brent and I talked some more in between songs. It was like having a bilingual conversation—shifting in and out of singing and talking until there stopped being a difference. After a while Brent started doing other people's music—"Silver Wings" and

"Faded Love" and "Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground." Stuff that reminded me of my dad's record collection. God forbid maybe I even mumbled along with Brent as he sang.

Things got blurry after that, but I remember during one of the silent places saying, "Les hasn't played straight with anybody this whole time. He wouldn't be worth protecting."

I wanted to look at him, see his reaction, but my eyes were closed and I was enjoying them that way.

"I gave up on protection a long time ago," Brent said.

His voice was a sad sound, the chords bright and airy behind it.

43

The last thing I remember, he was singing something about a train.

I woke up with the feeling that somebody had hooked me to a reverse IV. All the fluid had ^r drained out of my mouth and my eyes and my brain. When I moved my head everything turned white. I realized, belatedly, that I was feeling pain.

I sat up on the metal cot and rubbed my face where it had pressed itself into the texture of the rayon. One of the yellow curtains was open and light was pouring directly onto my chest.

Other things came into focus—a folding card table with a bucket of silverware on it. A wooden bunk bed, the bottom bunk stripped to the springs. A Playboy wall calendar that was still stuck on Miss August. The walls were the same inside the little tractorshed apartment as they were outside—rough wood, painted red. What few pictures there were hung from bare nails. Brent's carving knife was stuck directly into the wall above the tiny sink. There was no oven—no kitchen to speak of. Just a hot pad and a coffeemaker and a minirefrigerator.

It was possible that a woman might've lived here once, but you couldn't've proved it.

I tried to get up.

I tried again.

When I finally succeeded I realized where all the fluid in my body had drained to. I looked around for the rest room.

It was a tiny closet behind a shower curtain. Everything was close together. The sink overlapped the toilet tank and the shower drained directly into the tile floor so you could, conceivably, use the toilet and take a shower and brush your teeth all at the same time.

I only tried option number one.

It wasn't until I rummaged in the medicine cabinet, hoping for aspirin, that I found some reminder of the woman who had once lived here—orange prescription bottles, at least ten of them, all typed faintly with the name Maria Daniels. Insulin A. Prenatal vitamin supplements. Glucophage. Several other names I hadn't ever heard of. Some were open, as if she'd just taken her prescription this morning. As if nothing had been touched in the cabinet in two years. In the corner, behind the container of white Glucophage tablets, was a baby teether still in its plastic wrapper.

I picked it up. Little glittery shapes—diamonds, squares, stars—floated through the liquid inside the plastic ring, sluggish and sterile.

Behind me Brent Daniels said, "You're up."

I closed the cabinet.

When I turned Brent was trying his best not to notice what I'd been doing. He fingered the edge of the shower curtain.

His hair had dried, and his face was cleanshaven. Except for the eyes, he didn't look like a man who'd been drinking as heavily as I had.

"Miranda called," he told me. "Said Milo was going to be mixing for the rest of the afternoon and did I want to pick her up early. I could, or—? "

"I'll drive up."

Brent nodded, like it was bad news he'd been expecting. He gestured behind him with his chin. I followed him out into the apartment, which was just big enough for the two of us.

Brent opened a cabinet above the little refrigerator and retrieved a bag of flour tortillas and a can of refried beans.

"Hungry?"

My stomach did a slow roll. I shook my head no.

Brent shrugged and cranked up the hot pad. I stared at the picture that was taped inside the pantry door—a black and white of a woman with short brunette hair, a slightly moonish face, an almost uncontainable smile, like she was being tickled.

"That Maria?"

Brent tensed, looked around to see what I was talking about. When he realized I meant the picture he relaxed.

"No. My mother."

"You were how old?"

He knew what I meant. "Almost twenty." Then, like it was something he was obliged to add, something he'd been corrected on many times, "Miranda was only six."

Brent threw a tortilla directly on the hot pad. He watched as it began to puff up and bubble. The tortilla was probably old and flat but after a minute on the grill it would taste almost as good as fresh. The only correct way to heat a tortilla.

"Willis might not be too happy with you driving to pick Miranda up," he speculated.

"But you don't mind."

He flipped the tortilla. One of the air bubbles had cracked open and the edges had blackened.

"Maybe I will take some," I decided.

Brent made no comment, but got another tortilla out of the bag.

"I don't mind," he finally agreed. "Dad ..." He trailed off.

"He's got an unpredictable temper, doesn't he?"

Brent was staring at the picture of his mother.

" 'Billy Senorita,' " I said. "The only song Miranda wrote herself—it was about your parents."

Brent stirred up the refried beans. "The fights weren't as bad as that."

" But scary to a sixyearold."

Brent stared at me. He let a little anger burn through the dead ash. "You want to think about something– think how Willis feels, hearing that song every night. Put him in his place, all right. Worked like a charm."

I did what Brent said. I thought about it.

Brent added a little pepper and a little butter and salt to the beans. When they were smoking he spread them on the flour tortillas, folded them, and handed one to me. We sat and ate.

I stared out the side window into the tractor shed. An enormous orange cat was sleeping on the seat of the rusty John Deere. A couple of doves were in the rafters above. My gaze shifted over to the ceiling above me.

"What's up there?" I asked.

"Attic now. Used to be the sewing room."

"Sewing?"

Brent looked at me, a little resentful that he had to say anything else. "Maria."

I turned my attention back to my bean roll.

"I want to tell you something," I decided.

Brent waited, not concerned one way or the other.

Maybe it was his passivity that made me want to talk. Maybe the midday whiskey hangover. Maybe it was just easier than telling his sister. Whatever it was, I told Brent Daniels pretty much the whole story—about Sheckly's bootlegging, about Jean Kraus, about how people that were in a position to give information on Sheckly's business were disappearing, either by choice or not.

Brent listened quietly, eating his bean roll. Nothing seemed to shock him.

When I was done he said, "You don't want to go telling Miranda all this. It'll kill her right now. Wait for her to finish her tape."

"Miranda may be in danger. You too, for that matter.

What was Jean Kraus arguing with you about—that night at the party?"

Brent smirked. "Jean, he'll argue about anything. That don't mean he's going to kill me and my family."

"I hope you're right. I hope Les doesn't bring you folks the kind of luck he brought Julie Kearnes. Or Alex Blanceagle."

Brent's eyes started collecting shadows again. "Miranda doesn't need this."

"But you're not concerned. You don't worry about Les making problems for you."

Brent shook his head slowly.

He was a hard person to judge. There could've been a lie there. Or maybe not. The weathered face and the years of hardness covered up just about everything.

"Tough for me to let somebody in here," he said finally. He stared off at the rough red walls of the apartment.

I sat there for another few seconds before I realized he'd just told me to leave.