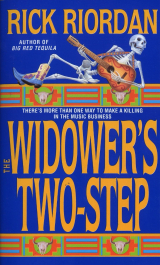

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

THE WIDOWER’S TWO STEP

Rick Riordan

So hold on, little darlin', 'cause the music is stern, Twirl 'round the cradle 'til your soul starts to burn, And don't say the next dance we won't get a turn 'Cause the Widower's TwoStep is a hard one to learn.

–"THE WIDOWER'S TWO STEP," Brent & Miranda Daniels

1

"Could you please tell your kid to be quiet?" The guy standing in front of my park bench looked like he'd stepped off a Fleetwood Mac album cover, circa 1976. He had that Lindsey Buckingham funhousemirror kind of body—unnaturally tall, bulbous in the wrong places. He had the 'Fro and the beard and the loosefitting black martial arts pyjamas that just screamed mod.

He was also blocking my camera angle on the blue '68 Cougar across San Pedro Park, eighty yards away.

"Well?" Lindsey wiped his forehead. He'd walked over from his tai chi group and sounded out of breath, like he'd been working the moves too hard.

I checked my watch. If the lady in the Cougar was going to meet somebody, it should've happened by now.

I looked at the tai chi guy.

"What kid?"

A few feet to my left, Jem made another pass on the swing set, strafing Lindsey Buckingham's students as he came down. He made airplane sounds at the top of his lungs, which was a lot of lungs for a fouryearold, then pointed his toes like machinegun barrels and started firing.

I guess maybe it was hard for Lindsey's folks to concentrate. One of them, a short ovoid woman in pink sweats, was trying to squat for Snake Creeps Down. She ended up rolling on her rump like she'd been shot.

Lindsey Buckingham rubbed the back of his neck and glared at me. "The kid on the swings, dumbass."

I shrugged. "It's a playground. He's playing."

"It's seventythirty in the morning. We're practicing here."

I looked over at Lindsey's students. The pink ovoid woman was just getting up. Next to her a little Latina lady was doing her moves nervously, pushing the air with her palms and keeping her eyes tightly shut as if she was afraid of what she might touch. Two other students, both middleaged Anglo guys with potbellies and pony tails, lumbered through the routine as best they could, frowning, sweating a lot. It didn't look like anybody was achieving inner tranquillity.

"You should tell them to keep their feet at fortyfive degrees," I suggested. "That's an unbalanced stance, parallel footing like that."

Lindsey opened his mouth like he was about to say something. He made a little cough in the back of his throat.

"Excuse me. I didn't know I was talking to a master."

"Tres Navarre," I said. "I usually wear a Tshirt, says 'Master.' It's in the wash."

I looked past him, watching the Cougar. The lady in the driver's seat hadn't moved.

Nobody else was in the San Antonio College parking lot.

The sun was just starting to come up over the white dome of the campus planetarium, but the night cool had already burned out of the air. It was going to be another ninetydegree day. Smells from the breakfast taqueria down on Ellsworth were starting to drift through the park—chorizo and eggs and coffee.

On the swing set Jem came down for another run.

"Eeeeoooooowwww," he shouted, then he made with the machine guns.

Lindsey Buckingham glared at me. He didn't move out of the way.

"You're blocking my view of the parking lot," I told him.

"Oh, pardon me."

I waited. "Are you going to move?"

"Are you going to shut your kid up?"

Some mornings. It's not bad enough it's October in Texas and you're still waiting for the first cold front to come through. It's not bad enough your boss sends her fouryearold with you on surveillance. You've got to have Lindsey Buckingham in your face, too.

"Look," I told him, "see this backpack? There's a Sanyo TLS900 in there—pinhole lens, clear resolution from two hundred yards, but it can't see through idiots. In a minute, if you move, I might get some nice footage of Miss Kearnes meeting somebody she's not supposed to be meeting. My client will pay me good money. If you don't move I'll get some nice footage of your crotch. That's how it works."

Lindsey scratched some sweat droplets out of his beard. He looked at the backpack.

He looked at me.

"Bullshit."

Jem kept swinging higher and shouting louder. His skinny brown legs were pinched into an hourglass shape by the swing. When he got to the top he went weightless, silky black hair sticking up like a sea urchin, his eyes wide, his smile way too big for his face.

Then he got a look of evil determination and came swooping down on the tai chi students again, machine guns blazing. The OshKosh B'Gosh Luftwaffe.

"Don't suppose you guys could move your class," I suggested. "Nice place over there by the creek."

Lindsey looked indignant. " 'What is firmly established cannot be uprooted.' "

I would've been okay if he hadn't quoted Laotzu. That tends to irritate me. I sighed and got up from the bench.

Lindsey must've been about six feet five. Standing straight I was eye level with his Adam's apple. His breath smelled like an Indian blanket.

"Let's push hands for it, then," I said. "You know how to push hands?"

He snorted. "You're kidding."

"I go down, I move. You go down, you move. Ready?"

He didn't look particularly nervous. I smiled up at him. Then I pushed.

You see the way most guys push each other—hitting the top of each other's chest like bullies do it on television. Stupid. In tai chi the push is called liu, "uproot." You sink down, get the opponent under the rib cage, then make like you're prying a big tree out of the ground. Simple.

When Lindsey Buckingham went airborne he made a sound like a hard note on a tenor sax. He flew up about two feet and back about six. He landed hard, sitting down in front of his students.

On the swing, Jem cut the machine guns midstrafe and started giggling. The ponytail guys stopped doing their routine and stared at me.

The lady in the pink sweats said, "Oh, dear."

"Learn to roll," I told them. "It hurts otherwise."

Lindsey got to his feet slowly. He had grass in his hair. His underwear was showing.

Standing doubled over he was just about eye level with me.

"God damn it," he said.

Lindsey's face turned the colour of a pomegranate. His fists balled up and they kept bobbing up and down, like he was trying to decide whether or not to hit me.

"I think this is where you say, 'You have dishonoured our school,' " I suggested. "Then we all bring out the nunchakus."

Jem must've liked that idea. He slowed down his swing just enough to jump off, then ran over and hung on my left arm with his whole weight. He smiled up at me, ready for the fight.

Lindsey's students looked uncomfortable, like maybe they'd forgotten the nunchaku routine.

Whatever Lindsey was going to say, it was interrupted by two sharp cracks from somewhere behind me, like dry boards breaking. The sound echoed thinly off the walls of the SAC buildings.

Everybody looked around, squinting into the sun.

When I finally focused on the '68 blue Cougar I was supposed to be watching, I could see a thin curl of smoke trailing up from the driver's side window.

Nobody was around the Cougar. The lady in the driver's seat still hadn't moved, her head reclined against the backrest like she was taking a nap. I had a feeling she wasn't going to start moving anytime soon. I had a feeling my client wasn't going to pay me good money.

"Jesus," said Lindsey Buckingham.

None of his students seemed to get what had happened. The potbellied guys looked confused. The ovoid lady in the pink sweats came up to me, a little fearful, and asked me if I taught tai chi.

Jem was still hanging on my arm, smiling obliviously. He looked down at his Crayoladesigned Swatch and did some time calculations faster than most adults could.

"Ten hours, Tres," he told me, happy. "Ten hours ten hours ten hours."

Jem kept count of that for me—how many hours I had left as an apprentice for his mother, before I could qualify for my own P.I. license. I had told him we'd have a party when it got to zero.

I looked back at the blue Cougar with the little trail of smoke curling up out of the window from Miss Kearnes' head.

"Better make it thirteen, Bubba. I don't think this morning's going to count."

Jem laughed like it was all the same to him.

2

"What is it with you?" Detective Schaeffer asked me. Then he asked Julie Kearnes,

"What is it with this guy?"

Julie Kearnes had no comment. She was reclining in the driver's seat of the Cougar, her right hand on a battered brown fiddle case in the passenger's seat, her left hand clenching the recently fired pearlhandled .22 Lady smith in her lap.

From this angle Julie looked good. Her greying amber hair was pulled back in a butterfly clasp. Her lacy white sundress showed off the silver earrings, the tan freckled skin that was going only slightly flabby under her chin, around her upper arms. For a woman on the wrong side of fifty she looked great. The entrance wound was nothing—a black dime stuck to her temple.

Her face was turned away from me but it looked like she had the same politely distressed expression she'd given me yesterday morning when we'd first met—a little smile, friendly but hesitant, some tightness in the wrinkles around her eyes.

"I'm sorry," she'd told me, "I'm afraid—surely there's been some mistake."

Ray Lozano, the medical examiner, looked in the shotgun window for a few seconds, then started talking to the evidence tech in Spanish. Ray told him to get all the pictures he wanted before they moved the body because the backrest was the only thing holding that side of her face together.

"You want to use English here?" Schaeffer said, cranky.

Ray Lozano and the tech ignored him.

Nobody bothered turning off the country and western music that was playing on Julie Kearnes' cassette deck. Fiddle, standup bass, tight harmonies. Peppy music for a murder.

It was only eightthirty but we were already getting a pretty good crowd around the parking lot. A KENSTV mobile unit had set up at the end of the block. A few dozen SAC students in flipflops and shorts and Tshirts were hanging out on the grass outside the yellow tape. They didn't look too interested in getting to their morning classes. The 7Eleven across San Pedro was doing a brisk business in Big Gulps to the cops and press and spectators.

"Tailing a goddamn musician." Schaeffer poured himself some Red Zinger from his thermos. Ninety degrees and he was drinking hot tea. "Why is it you can't even do that without somebody getting dead, Navarre?"

I put my palms up.

Schaeffer looked at Julie Kearnes. "You can't hang around this guy, honey. You see what it gets you?"

Schaeffer does that. He says it's either talk to the corpses or take up hard liquor. He says he's already got the lecture picked out he's going to give my corpse when he comes across it. He's fatherly that way.

I looked across the parking lot to check on Jem. He was sitting in my orange VW

convertible showing one of the SAPD guys his magic trick, the one with the three metal hoops. The officer looked confused.

"Who's the kid?" Schaeffer asked.

"Jem Manos."

"As in the Erainya Manos Agency?"

" 'Your fullservice Greek detective.' "

Schaeffer's face went sour. He nodded like Erainya's name in this case explained everything.

"The Dragon Lady ever hear of day care?"

"Doesn't believe in it," I said. "Kid could catch germs."

Schaeffer shook his head. "So let me get this straight. Your client is a country singer.

She prepares a demo tape for a record label, the tape turns up missing, the agent suspects a disgruntled band member who would've been cut out of the record deal, the agent's lawyer gets the brilliant idea of hiring you to track down the tape. Is that about it?"

"The singer is Miranda Daniels," I said. "She's been in Texas Monthly. I can get you an autograph if you want."

Schaeffer managed to contain his excitement. "Just explain to me how we got a fiddle player dead in the SAC parking lot seventhirty Monday morning."

"Daniels' agent figured Kearnes was the most likely suspect to steal the tape. She had access to the studio. She'd had some pretty serious disagreements with Daniels over career plans. The agency thought Kearnes might've stolen the tape at someone else's prompting, somebody who stood to gain from Miranda Daniels remaining a local act.

As near as I could tell that wasn't the case. Kearnes didn't have the tape. Didn't mention it to anybody over the last week."

"This is not explaining the dead body."

"What can I tell you? Yesterday I finally talked to Kearnes, told her straight what she was being accused of. She denied knowing anything but seemed pretty shaken up.

Then when she bolted out the door this morning I figured maybe I'd been mistaken about her innocence.

Maybe I'd stirred things up and she'd arranged to meet with whoever'd asked her to steal the tape."

Ray Lozano moved Julie's fiddle case off the passenger seat. He sat next to her. He began picking fragments out of her hair with tweezers.

"Stirring things up," Schaeffer repeated. "Nice fucking method."

One of the campus cops came over. He was a heavy guy, a former boxer maybe, but you could tell he hadn't dealt with homicides before. He approached Julie Kearnes the way most people do the first time they see a corpse—like an acrophobic sneaking up to the railing of a balcony. He nodded at Schaeffer, then looked sideways at Julie.

"They want to know about how much longer it'll be." He said it apologetically, like they were being unreasonable. "She committed suicide in the bursar's parking space."

"What suicide?" Schaeffer said.

The big guy frowned. He looked down uncertainly at the gun in Julie's hand, then the little hole in her head.

Schaeffer sighed, looked at me.

"She was shot from a distance," I explained. "You shoot yourself pointblank the wound splits like a star. Plus the entrance and exit wounds here are angled down and the calibre of the gun is probably wrong. The shooter was up there somewhere." I pointed to the top of a campus building where there was a series of big metal airconditioning units making steam. "She was carrying the .22 for protection. Fired it when she was hit because of a cadaveric spasm. The bullet's probably embedded in the dashboard."

Schaeffer listened to my explanation, then waved his free hand in a soso gesture.

"Make yourself useful," he told the campus cop. "Go tell the bursar to park it on the street."

The big man walked away a lot faster than he'd walked up.

A crime scene unit detective came over and pulled Schaeffer aside. They talked. The CSU guy showed Schaeffer some ID and business cards from the dead woman's wallet. Schaeffer took one of the cards and scowled at it.

When Schaeffer came back to me he was quiet, drinking Red Zinger. His eyes over the thermos cup were the same colour as the tea, reddish brown, just about as watery.

He handed the card to me. "Your boss?"

The words LES SAINTPIERRE TALENT were printed maroon on gray. Cantered underneath in smaller type it said: MILO CHAVEZ, ASSOCIATE. I stared at the name

"Milo Chavez." It did not invoke feelings of goodwill.

"My boss."

"I don't suppose you came across any reasons why somebody would want to kill this lady. And don't tell me the fucking demo tape was that good."

"No," I agreed. "It was not."

"You look for large debts, irate boyfriends—the kind of background work real P.I.s do when they're not minding threeyearolds?"

I tried to look offended. "Jem's a mature fouranda half."

"Uhhuh. Why meet somebody here? Why drive the seventyfive miles from Austin to San Antonio and park at a junior college?"

"I don't know."

Schaeffer tried to read my face. "You want to give me anything else?"

"Not especially. Not until I talk to my client."

"Maybe I should let you make that call from a holding cell."

"If you want."

Schaeffer dug a red handkerchief the size of Amarillo out of his pants pocket and started blowing his nose. He took his time doing it. Nobody blows his nose as often and as meticulously as Schaeffer. I think it's how he meditates.

"I don't know how Erainya got you this case, Navarre, but you should shoot her for it."

3

"Actually I know the agent's assistant, Milo Chavez. I was doing Chavez a favour."

Ray Lozano was talking with the paramedics about how to move the corpse. The crowd of college kids outside the police tape was getting bigger. Two more uniforms were leaning on the side of my VW now, watching Jem put his magic rings together.

The cowboy fiddle tunes were swinging right along on Miss Kearnes' cassette deck.

Schaeffer finally put his handkerchief away and looked down at Julie Kearnes, still clenching, her .22 like she was afraid it might jump out of her lap.

"Hell of a favour," Schaeffer told me.

All the way back to the North Side I had to give Jem a lecture about not taking bets on magic tricks from the nice policemen.

Jem nodded like he was listening. Then he told me he could do six rings at a time and did I want to bet?

"No thanks, Bubba."

Jem just smiled at me and pocketed his three new quarters in his OshKosh overalls.

It would've been faster to take McAllister Freeway back to Erainya's office, but I headed up San Pedro instead. Going north on the highway, twenty feet off the ground the whole way, all you see are the hills and the Olmos Basin, a few million live oaks, an occasional cathedral spire, and the tops of some Olmos Park mansions. Clean and forested, like there's no city at all under there. San Pedro is more honest.

For about two miles north of SAC, San Pedro is the dividing line between Monte Vista and the beginning of the West Side. On the right are the old Spanish mansions, huge acacia and magnolia trees, shaded lawns with Latino gardeners tending the roses, Cadillacs in the wraparound flagstone drives. On the left are the boardedup apartment blocks, the occasional momandpop ice house selling fresh watermelons and Spanish newspapers, the tworoom houses with kids in Goodwill clothes peering out the screen doors.

Go two miles farther up and the bilingual billboards disappear. You drive past white middleclass housing developments and rundown shopping centres from the sixties, streets that were named after characters in I Love Lucy. The land gets flatter; the ratio of asphalt to trees gets worse.

Finally you get to the mirrored office buildings and the singles apartment complexes clustered around Loop 410. Loopland could be in Indianapolis or Des Moines or Orange County. Lots of character.

Erainya's office was in an old white strip mall off 410 and Blanco, between a restaurant and a leather furniture outlet. The parking lot was empty except for Erainya's rusty Lincoln Continental and a newish mustardyellow BMW.

I pulled in next to the Lincoln and Jem helped me put up the ragtop on the VW. Then we got our respective backpacks out of the trunk and went to find his mom.

The black stencil sign on the door said, THE ERAINYA MANOS AGENCY, YOUR FULLSERVICE GREEK DETECTIVE.

Erainya likes being Greek. She tells me Nick Charles in The Thin Man was Greek. I tell her Nick Charles was rich and fictional; he could be anything he wanted. I tell her she starts calling me Nora I'm quitting.

The door was locked. The miniblinds across the glass front of the office were pulled down. Erainya had stuck one of those cardboard black and white pointing hands over the mail slot, pointing right.

We went next door to Demo's and almost collided with a stocky Latino man on his way out.

He wore a threepiece suit, dark blue, with a gold watch chain and a wide maroon tie.

He had four gold rings and a zircon tie stud and smelled strongly of Aramis. Except for the bulldog expression, he looked like the kind of guy who might offer you credit toward a purchase of fine diamond jewellery.

"Barrera." I smiled. "What's new, Sam—you come by to get some pointers from the competition?"

Samuel Barrera, senior regional director for ITech Security and Investigations, didn't smile back. I'm sure at some point in his life, Barrera must've smiled. I'm also sure he would've been careful to eliminate any witnesses to the event. The skin around his eyes was two shades lighter brown than the rest of his face and bore permanent oval rings from all those years wearing FBI standardissue sunglasses, before he'd retired into the private sector. He never wore the glasses these days. He didn't need to anymore. The glossy, inscrutable quality had sunk directly into his corneas.

He looked at me with mild distaste, then looked at Jem the same way. Jem smiled and asked Barrera if he wanted to see a magic trick. Barrera apparently didn't. He looked back at me and said, "My conversations are with Erainya."

"See you later, then."

"Probably so." He said it like he was agreeing that a sick horse probably needed to be shot. Then he brushed past me and got into his mustardyellow BMW and drove away.

I stood watching the intersection of 410 and Blanco until Jem tugged on my Tshirt and reminded me where we were. We went inside the restaurant.

Two hours before the lunch crowd, Manoli was already behind the kitchen counter carving gyro strips off a big column of lamb meat. It seemed like every time I came in the column of lamb got skinnier and Manoli got thicker.

The place smelled good, like grilled onions and fresh baked spanakopita. It wasn't easy to get a Mediterranean feel in a strip mall, but Manoli had done what he could—

whitewashed walls, a couple of tourist posters from Athens, some Greek instruments on the wall, bottles of Uzo on each table. Nobody came here for the decor anyway.

Erainya was sitting on a bar stool at the counter, talking to Manoli in Greek. She wore high heels and a Tshirt dress, black of course. She looked up when I came in, then lifted one bony hand and slapped the air like it was the side of my face.

"Ah, this guy," she said to nobody in particular, disgusted.

Manoli pointed his cleaver at me and grinned.

Jem ran up to his mom and hugged her leg. Erainya managed to tousle his hair and tell him he was a good boy without softening the look of death she had aimed at me.

Erainya's eyes are the only thing big about her. They're huge and blackirised, almost bugeyed except they're too damn intense to look funny. Everything else about her is small and wiry—her black hair, her bony frame under the Tshirt dress, her hands, even her mouth when she frowns. Like she's made out of coat hangers.

Erainya slid off the bar stool, came up to me, and frowned some more. She stands about five feet tall in the heels, but I've never heard anybody describe her as short. A lot of other things, but never short.

"You got my phone message?" I asked. "I got it."

"What did Barrera want?"

"Let's get a table," she told me.

We did. Manoli sat Jem on the counter and started talking to him in Greek. Jem doesn't understand Greek, as far as I know, but it didn't seem to bother either of them.

"All right," Erainya said. "Give me details."

I told her about my morning. About halfway through she started shaking her head no and kept shaking it until I'd finished.

"Ah, I don't believe this," she said. "How is it you convinced me to let you do this case?"

"Masculine charm?"

She scowled at me. "You look good, honey. Not that good."

Erainya smiled. She looked out the restaurant window, checking the office. Nobody was beating down the door of the Erainya Manos Agency. No crowds were queuing up for a fullservice Greek detective.

"Why was Barrera here?" I asked again.

Erainya slapped the air. "Don't worry about that vlaka, honey. He just likes to check up on me, make sure I'm not stealing his business."

It was a point of pride so I nodded like I believed it. Like Barrera needed Erainya's divorce cases and employee checks to stay afloat. Like his security contracts with half the companies in town wasn't enough.

For the millionth time, I looked at Erainya and tried to imagine her back in the days when that competition had been real—back when her husband Fred Barrow was still alive and in charge of the agency and Erainya was Anglicized as Irene, the good little assistant to her husband the sortof famous P.I. That was before she'd shot Barrow in the chest. Then he'd been sortof dead.

The judge had said it was selfdefence. Irene had said God rest Fred's soul. Then she'd cashed in her husband's stocks and returned to the Old Country and come back a year later as Erainya (rhymes with Transylvania) Manos, tan and very Greek, mother of an adopted Moslem Bosnian orphan whom she'd named after somebody in a novel she'd read. She'd taken over her husband's old agency and become an investigator like it had been her destiny all along. Business had been sliding ever since.

Two years ago, when I'd just moved back to town and was thinking about going legit as a licensed investigator, one of my dad's old SAPD friends who didn't know Barrow was dead had recommended Fred as the secondbest P.I. in town to apprentice with, just after Sam Barrera.

After Sam and I had decidedly failed to hit it off I'd gone to Fred Barrow's office address and discovered in the first thirty seconds I was there that Erainya was the trainer for me.

Is Mr. Barrow here?

No. He was my husband. I had to shoot him.

"That's it on the Kearnes case, then," Erainya was saying. "You got what—twenty hours left?"

I hesitated. "Jem says ten."

"Ah, only ten? It's twenty. Anyway, we've got other things to do."

"You said I could do this."

Erainya tapped her fingers on the Formica table. They sounded hard, like pure bone.

"I said you could try, honey. Somebody gets murdered, that's the end of it. It's a police matter now."

I stared at the picture of Athens behind her head.

Erainya sighed. "You don't want to have this conversation again, do you?"

"What conversation? The one where you explain why you can't pay me anything this week, then you ask me to babysit?"

Her eyes got very dark. "No, honey, the one where we talk about why you want to do this job. You spend a few years in San Francisco doing armbreaking for some shady law firm, you think that makes you an investigator? You think you're too good for a regular caseload—you'll just keep churning the ones that interest you?"

"You're right," I said. "I don't want to have this conversation again."

Erainya muttered something in Greek. Then she leaned toward me across the table and switched to English midsentence.

"—tell you this. You think you're a big deal, coming back to town with your Berkeley Ph.D. and whatever. Okay. You think you're too good to apprentice because you've been on the streets awhile. Okay too."

"I did teach you the trick with the superglue."

She used both hands this time, going out on either side of her face like she was slapping people sitting next to her.

"Okay, so you show me one thing. It's even all right you think you want to do this because your dad was a cop. You think you want to do personal favours once in a while, do something out of charity—all right, fine. But that's not what you do to make a living, honey. The job is hard work, which you keep trying not to notice, and mostly it's not personal. You sit in a car for eight hours with intestinal problems taking pictures of some sleaze ball because another sleaze ball paid you to. You look at old deeds and talk to boring credit bureau men that aren't even goodlooking. You keep the police happy, which means you stay away from anything where people end up dead. Mostly you don't make much money so, yeah, maybe you do have to take your kid along sometimes. I'm talking about the breadandbutter work. I don't know if you can handle that part of it, honey. I still don't know that about you."

"If you're not going to recommend me to the Board," I said, "now would be a good time to say so."

The coat hangers that made up Erainya's body seemed to loosen a little bit, and she sat back in her chair. She looked out the window again, checking for clients. Still no lines outside the office.

"I don't know," she said. "Maybe not. Not if you can't take a case when it's good and drop a case when it's bad. As long as you're operating under my license I can't risk you getting it revoked."

I examined her face, trying to determine why the warning she'd thrown out so many times before had a harder edge this time.

"Barrera said something to you," I guessed. "He's got pull with the Board. Was he pressuring you about me?"

"Don't be dumb, honey."

"I just watched a woman get murdered, Erainya. I'd like to know why. I could at least—"

"That's right," she said, sitting forward again. "You shake up that Kearnes woman one day and she runs out and gets herself killed the next. What does that tell you about your methods, honey? It tells me you should listen sometimes. You don't blow a surveillance because you're getting impatient. You don't ring the subject's doorbell and ask them to confess to you."

The rims of my ears felt hot. I nodded. "Okay."

Fingers on the Formica. "Okay what?"

"Okay maybe I'll quit. Withdraw. Unapprentice. Whatever you call it."

She waved her hand dismissively. "Ah, what, after this many months?"

I got up.

She stared at me for a few seconds, then looked back out the window like it didn't matter one way or the other to her. "Whatever you want to do, honey."

I started to leave.

When I was at the door she called me. She said, "Think about it, honey. We could treat it as time off. Tell me next week."

I looked over at Manoli, who was telling Jem something in Greek. It must've been a fairy tale, by the tone and the gestures he was using.

"I told you today, Erainya."

"Next week," she insisted.

I said sure. Before I could leave, Jem looked over and asked me what kind of party we would have when my hours got to zero. He wanted to know what kind of cake.

I told him I'd have to think about it.