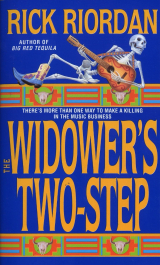

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

11

I met Hayseed halfway across the room and heel kicked him in the shin to take his mind off the gun. He grunted, stumbled forward one more step, his hands moving down instinctively toward the pain.

I grabbed his shoulders and forced him backward. When he tipped over the side of the easy chair, his knees went up and his butt sank and the back of his head hit the mixing board. The equalizer lights did a crazy little surge. His bottle of Captain Morgan's toppled over, speckling the controls with rum.

Hayseed stayed put, his arms splayed and his knees up around his ears in hogtie position. He made a little groaning sound in his throat, like he was showing displeasure at a very bad pun.

I extracted a .38 revolver from his shoulder holster, emptied its chambers, threw gun and bullets into a nearby milk crate. I found his wallet in the pocket of his windbreaker and emptied that, too. He had twelve dollars, a driver's license that read ALEXANDER

BLANCEAGLE, 1600 MECCA, HOLLYWOOD PARK, TX, and a Paintbrush Enterprises business card identifying him as Business Manager.

I looked at the mixing board. Rows of equalizer lights still bounced up and down happily. A bank of CD burners and digital disc drives were daisychained together, all with beady little green eyes, ready to go. There were six or seven chunky onegigabyte cartridges scattered across the board. I picked up the earphones Alex had been wearing and listened—country music, recorded live, male singer, nothing I recognized.

Behind the chair was an unzipped black duffel bag filled with more recording cartridges and some microphone cords and a bunch of paper folders and files I didn't have time to look through.

Blanceagle's groaning changed pitch, got a little more insistent.

I helped him untangle his legs from his ears, then got him seated the right way again.

His clothes fit him like a shortsheeted bed and his once nicely combed hair was doing a little swirly unicorn thing on top of his head.

He massaged his shin. "I need a damn drink."

"No, you damn don't."

He tried to sit up, then decided that didn't feel too good and settled back in. He tried to make some thick, fuzzy calculations in his head.

"You ain't Jean."

"No," I agreed. "I'm not."

"But Sheck ..." He knit his eyebrows together, trying to think. "You look a little—"

"Like Jean," I supplied. "So it would seem."

Alexander Blanceagle rubbed his jaw, pulled his lower lip. There was a little U of blood on the gum line under one of his teeth. "What'd you want?"

"Not to get mistaken for Jean and killed, preferably."

He frowned. He didn't understand. Our little dance across the room might've happened a hundred years ago, to somebody else.

"I'm here about a friend of yours," I said. "Julie Kearnes."

The name registered slowly, sinking in through layers of rumhaze until it went off like a depth charge somewhere far under the surface. Blanceagle's freckles darkened into a solid redbrown band across his nose.

"Julie," he repeated.

"She was murdered."

His eyebrows went up. His mouth softened. His eyes cast farther afield for something to latch on to. Nostalgia mode. I had maybe five minutes when he might be open to questions.

Not that drunks have predictable emotional cycles, but they do follow a brand of chaos theory that makes sense once you've been around enough of them, or been made an alumni yourself.

I overturned a milk crate, shook the electrical cords out of it, and sat down next to Blanceagle. I unfolded one of the airline receipts I'd taken from Sheckly's desk and handed it across. " You and Julie went to Europe together a couple of times on Sheckly's tab. Were you close?"

Blanceagle stared at the receipt. His focus dissipated again. His eyes watered up.

"Oh, man."

He curled forward and put the hand with the airline receipt against his forehead, the Great Karnak reading a card. He scrunched his eyes together and swallowed and started shuddering.

I'll admit to a certain manly discomfort when another guy starts to cry in front of me, even if he is drunk and funnylooking and recently guilty of trying to draw a gun on me.

I sat very still until Blanceagle got his body under control. One Muddy Waters, two Muddy Waters. Twentyseven Muddy Waters later he sat up, wiped his nose with his knuckles. He set the airline receipt on the arm of the chair and patted it.

"I got to go. I got to—"

He looked at the sound board, struggling to remember what he'd been doing. He started gathering up the one gigabyte cartridges, sticking them in his windbreaker pockets that were a little too small to hold them. I handed him one that kept slipping away.

"You're copying a lot of music here."

He stuffed the last of the discs in his pocket, then made a feeble attempt to clean the drops of Captain Morgan's Spiced Rum off the sound board's controls, wiping between the lines of knobs with his fingers. "Sheck is crazy. I can't just—I'm in six years deep now, he can't expect—"

Alex padded his shoulder holster, realized it was empty.

"Over there." I pointed. "Sheckly can't expect what?"

Blanceagle glanced over at his unloaded gun in the milk crate, then at me, suspicious how I'd pulled that off.

"What was your name?" he asked.

I told him. He repeated "Navarre" three times, trying to place it. "You know Julie?"

"I was tailing her the day she got murdered. Maybe I helped it happen by applying pressure on her at the wrong time. I don't feel particularly good about that."

Alex Blanceagle pulled together enough anger to sound almost sober. "You're another goddamn investigator."

"Another?"

He tried to maintain the glare but he didn't have the attention span or the energy or the sobriety for it. His eyes zigzagged down and came to rest on my navel.

He muttered unconvincingly, "Get out of here."

"Alex, you've had some kind of disagreement with Sheck. You're clearing out your stuff. It's got to be in connection with the other things that have been happening.

Maybe you should talk to me."

"Things will work out. You don't worry about Sheck, you understand? Les SaintPierre couldn't do it, I'll take care of it myself."

"Take care of what, exactly?"

Blanceagle looked down at his halfpacked duffel bag and wavered between anger and wistfulness. Maybe if I'd had more time and more Captain Morgan's I could've eventually plied him into a temporary friendship, but just then the door of the studio opened and my stunt double came in.

Jean did look enough like me that I couldn't label Alex a complete idiot for making the mistake. Jean was much thicker in every part of his body, though, slightly taller, his black hair curlier. He was also less comfortably and more expensively dressed—black boots, tight gray slacks, a black turtleneck, a gray linen jacket. It must've been a thousand degrees in those clothes. His left hand casually held a gray and black Beretta that matched his outfit perfectly. His eyes were the same colour as mine, hazel, but they were smaller and amorally fierce as a crab's. Put me on the GNC

highcal highfibre diet and force me to dress that way and I probably would've looked the same.

Jean looked around calmly. He zeroed in on the shoulder holster under Alex Blanceagle's windbreaker, dismissed it, then noticed Blanceagle's full pockets and the duffel bag. Finally he looked at me. That took a little longer.

Eyes still on me, Jean asked Alex a calm, threeword question in German. Blanceagle responded in the same language—a negative answer.

Jean held out his hand.

Alex struggled to his feet. He limped over to us, trying to keep the weight off his recently kicked shin. He started fumbling with his pockets, pulling out the recording cartridges one by one, and handing them to Jean.

Two of the discs clattered to the floor. When Alex bent over to get them, Jean kicked him in the ribs just hard enough to send Blanceagle sprawling. Jean did it without anger or change of expression, the way a kid might push over a rolypoly bug.

Alex stayed on the carpet, blinking, reorienting himself, then began the process of getting his limbs to work.

Jean's next question, still in German, was aimed at me.

I shrugged helplessly. Jean looked at Alex, who was now up on one elbow and seemed quite content to stay that way.

Blanceagle squinted up at me for a long time. He said, slowly and deliberately, "He's a steel player, for God's sake. I forgot to reschedule the fucking base track session tonight, is all."

Jean scrutinized me one more time, trying to burn a hole in my face with those little crab eyes. I tried to look like an ignorant steel guitar player. I managed the ignorant part pretty well.

Finally Jean nodded at the door. "Get out, then."

His English was perfect, the accent British. A German speaker with a French name and a British accent. It made about as much sense as anything else I'd come across so far. I looked down at Alex Blanceagle.

"Don't worry about those base tracks," Alex told me. "I'll take care of it."

There was absolutely no confidence in his voice.

As I left, Jean and Alex were having a very quiet, very reasonable conversation in German. Jean did most of the talking, slapping the gray and black Beretta against his thigh with a casual carelessness that reminded me very much of his boss, Tilden Sheckly.

When I got back to the main room I could've stuck around longer. Tammy Vaughn was just starting her first number, "Daddy Taught Me Dancin'." I wasn't a country fan but I had heard it once or twice on the radio and Tammy sounded fine. The two hundred or so folks on the dance floor looked like a paltry crowd in the vastness of the hall, but they were hooting and hollering their best. Tilden Sheckly was standing by the sound board, still having a lively argument with the woman in the skyblue jumpsuit. I could've asked a lot of questions, done some twostepping with bighaired women, maybe met a few more nice men with guns.

Instead I said goodbye to Leena the bartender. She was busy now, a bottle of tequila in either hand, but she told me to stick around for a while longer. Her break was coming up soon.

I told her thanks anyway. I'd had enough of the Indian Paintbrush for one night.

12

When I woke up Tuesday I stared at the ceiling for a long time. I felt queasy, disoriented, like I'd been looking through someone else's prescription lenses too long.

I groped along the windowsill until I found the business card from Julie Kearnes' wallet.

The words on it hadn't changed.

LES SAINTPIERRE TALENT MILO CHAVEZ, ASSOCIATE

Milo's wad of fifties was still there, too, not much lighter for my night on the town.

Finally I got up, did the Chen long form in the backyard, then showered and made migas for myself and Robert Johnson.

I checked the latest Austin Chronicle. Miranda Daniels was scheduled to start at the Cactus Cafe at eight P.M. After doing the dishes, I called my brother Garrett and left a message telling him surprise, we had plans tonight. I love my brother. I love having a free place to sleep in Austin even more.

I tried Detective Schaeffer at SAPD homicide. Schaeffer wasn't in. Milo Chavez wasn't in either.

I peeled off a stack of Milo's fifties, enough for my October rent, and left it in an envelope on the counter. Gary Hales would find it. Maybe, if things went well between now and next Friday, I would be able to spring for November too. But not yet.

I left extra water and Friskies on the kitchen counter and a piece of newspaper where Robert Johnson would, inevitably, throw up when he realized I was gone overnight.

Then I headed out for the VW.

I hit Austin just after noon and spent a few more fruitless hours visiting Les SaintPierre's hangouts, talking to people who hadn't seen him recently. This time I claimed to be a songwriter trying to get my tape to Les. I told everybody I had a great new surefire hit called "Lovers from Lubbock." I found it difficult to generate much excitement.

After a late lunch I swung by Waterloo Records on North Lamar and found a Julie Kearnes cassette from 1979 in the bargain bin. I bought it. There were no recordings by Miranda Daniels yet. There were quite a few CDs in the Texas Artist section on Sheckly's Split Rail label—such household names as Clay Bamburg and the Sagebrush Boys, Jeff Whitney, the Perdenales Polka Men. I didn't buy them.

I drove north on Lamar, right on Thirtyeighth, into Hyde Park, following the route I'd taken last week on surveillance. I turned left on Speedway and parked across the street from Julie Kearnes' house.

The Hyde Park neighbourhood is not quite as snooty as the name implies. It's equal parts college kid, aging hippie, and aging yuppie. It's got its share of bad elements—sleazy Laundromats, dilapidated student housing, Baptist churches. The streets are quiet, shaded by live oaks, and lined with quaintly rundown 1940s starter homes.

Julie Kearnes' place was just rundown, not quaint. Back in the sixties it had probably been what my brother Garrett called a "hobbit house." Above the door a round stainedglass peace sign window was now grimy and broken, and the comets and suns that had once been painted along the trim of the roof and windows had been thinly whitewashed over. The yellow front lawn was shaded by a pecan tree so infested with web worms it looked like a cotton candy stick. About the only thing that looked well tended was Julie's planter box underneath the livingroom window, full of purple and yellow pansies. Even those were starting to wilt.

Afternoon traffic on Speedway was heavy. An orange UT shuttle went by. Ford trucks with lawn mowers and rakes and whole Latino families in the back cruised for unkempt front yards. A good number of seventies Hondas and VW bugs puttered down the street with peeling bumper stickers like UNREAGANABLE and HONOR THE GODDESS.

Austin, the only city in Texas where my car is inconspicuous.

Nobody paid me any attention. Nobody stopped at the Kearnes residence. If the police had been here they hadn't left any obvious sign.

I was about to cross the street and let myself in when a guy stuck his head in my passenger's side window and said, "I thought that was you."

Julie's acrossthestreet neighbour had horse like features. He smiled and you expected him to bray or nuzzle you for a sugar cube. His saltandpepper hair was clipped close around the ears, gelled, spiky on top. He wore a blue buttondown shirt tucked into khaki walking shorts, tied with a multicoloured Guatemalan belt, and when he leaned into the car I didn't so much smell him as experience one of those surrealistic fifteen second designer cologne ads.

He grinned. "I knew you'd be back. I was sitting on my love seat having an espresso and I thought: I bet that police detective will be back today. Then I looked out the window and here you are."

"Here I am," I agreed. "Listen—was it Jose—?"

"Jarras. Jose Jarras." He started to spell it.

"That's great, Mr. Jarras, but—"

Jose held up one finger like he'd just remembered something vitally important and leaned farther into my car.

"Didn't I tell you?" he said, lowering his voice. "I told you something funny was going on."

"Yeah," I admitted. "You called it."

I wondered what the hell he was talking about. Maybe Julie's murder had made the Austin AmericanStatesman. Or maybe Jose was just percolating some of the great theories he'd offered me Saturday morning—how Miss Kearnes needed his help because the Mafia was after her, or the Feds, or the Daughters of the Republic of Texas.

Jose narrowed his eyes conspiratorially. "I started thinking about it after I talked to you.

I said to myself, why would the police be so interested in her? Why are they staking out her house? She's got one of those drug dealer boyfriends, doesn't she? She'll have to go into the witness protection program."

I told Jose he had a hell of a deductive mind.

"Poor dear's been super agitated," he confided. "She's stopped making those sugar cookies for me. Stopped saying hello. She's been looking like—well."

He waved his hand like I could easily imagine the crimes against fashion the poor dear had been perpetrating. I nodded sympathetically.

"She had that visitor Saturday night..."

"I know," I assured him. "We were watching the house."

The visitor had been one of Julie's girlfriends, an amateur aroma therapist named Vina whose innocuous life story I'd already delved into. Vina had come over to Julie's with her essential oil kit around eight and left around nine. I didn't want to tell Jose that the chances of Vina being a mafia hit man were pretty slim.

Jose leaned farther into my car. Another inch and he'd be in my lap.

"Are you going to break in?" he asked. "Check for traps?"

I assured him that it was standard procedure. Nothing to get alarmed about.

"Oh—" He nodded vigorously. "I'll let you get to work. Aren't you supposed to give me your card, in case I remember something later?"

"Give me your hand," I told him.

He looked uncertain, then thrust it at me. I took my permanent black marker off the dashboard and inscribed Jose's palm with Erainya's alternate voicemail number, the one that says: "You have reached the Criminal Investigations Division."

He frowned at it for a minute.

"Budget cutbacks," I explained.

When I got to Julie's front door it took me about two minutes to find the right dupe for the dead bolt. I leaned leisurely against the door frame, trying different keys and whistling while I worked. I smiled at an elderly couple walking by. Nobody yelled at me.

Nobody set off any alarms.

A licensed P.I. will tell you that committing crimes in the line of work is a myth. P.I.s gather evidence that might be used in court, and any evidence gathered illegally automatically ruins the case. So P.I.s are good boys and girls. They do surveillance from public property. They keep their noses clean.

It's ninety percent true. The other ten percent of the time you need to find out something or retrieve something that's never going to see its way into court, and the client—usually a lawyer—doesn't care how illegally you do it as long as you don't get caught and traced back to them. They'd just assume use somebody unprincipled and unlicensed who can play a discreet game of hardball. That's how I'd worked for five years in San Francisco– unprincipled and unlicensed. Then I'd moved back to Texas, where my dad's old friends on the force had put increasing pressure on me to get licensed and work right.

None of them wanted the embarrassment of busting Jack Navarre's kid.

I jimmied the side bolt. Then I took the two days' worth of mail from Julie's box and went inside.

The kitchen smelled like lemon and ammonia. The hardwood floors had been swept.

Copies of Fiddle Player and Nashville Today were neatly stacked on the glass topped fruit crate that served as a coffee table. There were fresh cut flowers on the dining table. She'd left an orderly home for someone who was never coming back to it.

I sat on the sofa and went through the mail. Bills. A letter from Tom and Sally Kearnes in Oregon and a pix of their new baby girl. The note said Can't wait for you to see Andrea! Love, T & S. I stared at the pink wrinkly face. Then I placed the photo and letter upside down on the coffee table.

I did a quick sweep of the back rooms. No messages on the answering machine.

Nothing to look at in the garbage can except moulding coffee grounds. The only thing interesting was on the top shelf of Julie's bedroom closet. Buried under a down comforter was a twotone brown suitcase like you'd see in a vaudeville act.

Inside on top were photos of Les SaintPierre. There was Les drinking beer with Merle Haggard, Les accepting an award from Tanya Tucker, young Les in a wide collared pink shirt, big curly hairdo, lots of polyester, standing next to a similarly dressed disco cowboy who was probably famous once but whom I didn't recognize.

Underneath the photos were lots of men's clothes, packed more like someone had been emptying drawers than picking things for a trip. It was all socks and jockey shorts. Or maybe that's what Les SaintPierre wore when he travelled. Maybe I'd been going to the wrong vacation spots.

I put the suitcase back.

In the den a green, hungrylooking parrot was sitting on its polished madrone branch.

He told me I was a noisy bastard and then went back to scratching ravenously at his cuttlebone.

I found some pistachios for him in the kitchen. Then I sat down at Julie's IBM PS/2 and stared at a dark screen.

"Dickhead," the parrot croaked. He cracked a pistachio.

"Pleased to meet you," I said.

The corkboard behind the computer was cluttered with paper. There was a dogeared picture of Julie Kearnes as a young fiddle player, her auburn hair longer, her body slimmer. She was standing next to George Jones. There was a more recent picture of the Miranda Daniels Band with Julie in the forefront. The photo was surrounded by concert reviews clipped from local papers, a few sentences about Julie Kearnes' fiddle playing highlighted in pink. One frontpage feature from the Statesman entertainment section showed just Miranda Daniels, standing between a standup bass and a wagon wheel with a fake sunset backdrop behind her. The title boldly announced: "The Rebirth of Western Swing: Why a new breed of Texas talent will take Nashville by storm."

A smaller corkboard to the left was more downto earth. It displayed $250 check stubs from Paintbrush Enterprises, also Julie's schedule and hourly pay scale for several jobs she'd taken through Cellis Temps in the last few months to make ends meet—basic word processing and data entry for an assortment of big corporations in town. Whether or not Miranda Daniels was going to take Nashville by storm, it didn't look like Julie Kearnes had been in any immediate danger of becoming affluent.

I looked through Julie's floppy disks. I opened the horizontal cabinet and took out a thin stack of mildewed blue folders. I was just starting to look through one labelled

"personal" when the front door opened and a man's voice said, "Anybody home?"

Jose tiptoed into the study, smiling apologetically, like he needed to pee real bad.

He looked around at the decor and said, "I had to see."

"You're lucky I didn't shoot you."

"Oh—" He started to laugh. Then he saw my face. "You don't really have a gun, do you?"

I shrugged and turned back to the files. I never carry, but I didn't have to tell him that.

Jose unfroze and began looking around the room, picking up knickknacks and checking titles on the bookshelf. The parrot cracked pistachios and watched him.

"Dickhead," the parrot said.

I gave the bird some more nuts. I believe in positive reinforcement.

On a quick look, Julie's "personal" file seemed to deal mostly with her debts. There were plenty of them. There was also some paperwork from Statewide Credit Counselling that suggested Julie had entered into debt negotiation about two months ago. The house, the parrot, and the '68 Cougar she was murdered in seemed to be her only assets. It looked like she had two mortgages on the house and was about one of Sheckly's pay checks away from becoming homeless.

I started Julie's IBM, figuring I'd do a quick check, take the hard disk with me and look at it more leisurely later on if anything seemed of worth.

There was nothing of worth. In fact, there was nothing at all. I sat there and stared at an empty green screen, a DOS prompt asking me where its brain had gone.

I thought for a second, then turned off the machine and pried off the casing. The hard drive was still in its slot. Erased, but not removed. That was good. I wrestled it out, wrapped it in newspaper, and stuck it in my backpack. A project for Brother Garrett.

"What is it?" Jose asked.

He'd come up behind me now and was peering over my shoulder, fascinated by the open computer. The cologne was intense. The parrot sneezed.

"Nothing," I said. "A lot of it. Somebody has tried to make sure there's nothing to be found on Julie Kearnes' computer."

Jose said, "It must've been that man who came over."

I stared at him. "What man?"

Jose looked exasperated. "That's what I was talking about outside—the man who came over Saturday night. You said you knew about him."

"Wait a minute."

I did a mental checklist. Saturday night, the night before I'd confronted Julie myself.

There hadn't been any man. I'd pulled standard surveillance, methods even Erainya couldn't have found fault with. I'd watched the house until elevenohfive, which had been lights out plus thirty minutes. At that point you can figure the subject is down for the count. I'd chalked Julie's tires, on the off chance she'd go somewhere during the night. Then I'd driven home for a few hours sleep before heading back to Austin at fourthirty the next morning.

"When did this guy come over?" I demanded.

Jose looked proud. "He banged on Julie's door at elevenfifteen. I remembered to check my clock."

The parrot ruffled his feathers and squawked, "Shit, shit, shit."

"Yeah," I agreed.