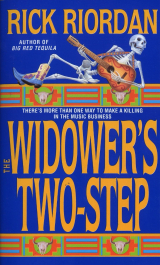

Текст книги "The Widower's Two-Step"

Автор книги: Rick Riordan

Жанры:

Разное

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

36

A red Mazda Miata was parked in front of 90 Queen Anne Street with its right tires over the curb. When I walked around to my side of the house Allison SaintPierre came out my front door and said, "Hi."

She was wearing white Reeboks, a pleated white skirt, and a white tank top that wasn't lining up with her bra straps very well. A terrycloth sweatband pushed her hair into bangs. Her smile was alcoholfortified. Tennis lesson day at the country club.

She was holding two Shiner Bocks. One bottle was almost empty. The other she gave to me.

"Damnedest thing," she said.

She leaned sideways in the doorway so I could pass if I wanted to do the mambo with her.

I stayed on the porch.

"Let me guess. My landlord let you in."

She smiled wider. "Sweet old fart. He picked up that envelope on the counter and asked me if I knew anything about this month's rent."

"Yeah, Gary has a thing for blondes. Rent money and blondes. Maybe if I brought over more blondes he'd ask less often about the rent."

Allison raised her eyebrows. "Worth a try."

Then she turned inside like her back was hinged to the doorjamb. I almost thought she was going to fall into the living room, but at the last minute she put her foot out and walked in. She said, "Wooo."

I drank some of my Shiner Bock before following her inside.

Allison had taken Julie Kearnes out of the cassette deck and put in my Johnny Johnson. She'd pulled an old Texas Monthly off the windowsill and left it open on the coffee table. The ironing board was down and the phone had been pulled out from behind it.

Allison sat on the kitchen counter stool and spread her arms along the Formica.

"Somebody named Carol called. I told her you weren't here."

"Carolaine," I corrected. "That's just great. Thanks."

She shrugged. Happy to help.

I looked for Robert Johnson but he'd buried himself deep. Maybe under the laundry.

Maybe in the pantry. Unlike my landlord, Robert Johnson didn't go much for blondes.

"You send Sheckly a getwell card yet?" I asked.

Allison had a happy drunk going that was about as thick as battleship skin. My question pinged against her, a small annoyance but not nearly enough to make her change course.

"One of his lawyers left me a message this morning– something about the medical bills." She was turning the tip of her right sneaker in time to the music. Back, forth, back, forth.

I waited.

"You're in my apartment for a good reason, I'm sure. Mind telling what it is?"

Allison appraised me while she bobbed her head, starting at my feet and working her way up. When she got to my eyes she locked on and smiled, approvingly.

"You look good. You should dress like that more often."

I shook my head. "This outfit reminds me of too many funerals."

"That's where you were this morning?"

"Close enough. Why are you here?"

Allison lifted her fingers off the counter. "You were listed in the book. I felt bad about you getting hit last night."

"You felt bad."

She grinned. " I'm not that terrible, sweetie. You don't know me well enough."

"The guys who know you well enough seem to get flesh wounds."

"Like I said, Tres, I grew up with four brothers."

"How many of them made it to adulthood?"

Her eyes sparkled. No making her mad today. "Maybe I was just curious. Miranda's dad called me this morning. He wanted to know if Miranda was with me last night."

"Yeah?"

She gave me a smirk. "Yeah. Seems she disappeared last night after the party. So did you, for that matter."

She waited for information.

Fortunately for me the phone rang. Allison offered to get it. I told her thanks anyway. I moved the phone to the bathroom doorway, which was as far as it would stretch, then picked up the receiver.

Erainya Manos said, "RIAA."

"Is that Greek?"

The next thing she said was Greek, and unflattering. "No, honey, I'm telling you something you never got from me. Recording Industry Association of America. When it comes to enforcing copyright laws in the music industry, they're it. They've got a branch office in Houston. For all of South Texas, they contract through Samuel Barrera."

I looked across the room at Allison. She smiled at me pleasantly, still moving her feet to the Johnny Johnson.

"That's great," I told Erainya. "I'm glad it was nothing serious."

Erainya hesitated. "You got visitors?"

"Uhhuh."

"Just listen, then. Sheckly's been in court half a dozen times the last few years, sued by bigname artists who've appeared at his place. They all claim he's taped their shows for syndication and given them no rights to anything, no percentage."

"I've heard about that."

"They also claim bootleg CDs of their shows have been turning up all over Europe.

Excellent quality recordings, made at firstrate facilities. My friends tell me it's pretty common knowledge Sheckly is the one making the tapes, getting a little extra money out of them. He speaks German, goes over to Germany frequently, probably uses the trips to strike some deals, distribute his masters, but nobody can prove it. Since the shows are taped for syndication they could've been copied and distributed at any radio station in the country, by anybody with the right equipment."

I smiled at Allison. I mouthed the words sick friend. "Doesn't sound like anything that would kill you. Just a minor annoyance."

Erainya was silent. "It doesn't sound like anything to get killed over, honey. You're right. Then again, how much money are we talking about? What kind of guy is Mr.

Sheckly? You got a sense for that?"

"I'm afraid I might. Why haven't they caught this before?"

"I hear Sheckly keeps things pretty modest. Doesn't import the music back into the U.S., which would make it more profitable but ten times easier to bust. He sticks to the European market, only live tapes. Makes him a lowpriority target."

"Got it."

"And, honey, you heard nothing from me."

"Room twelve. All right."

"If you can use this to squeeze Barrerra's balls a little bit—"

"I'll do that. Same to you."

I hung up. Allison looked at me and said, "Good prognosis?"

"You mind if I change clothes?"

She pursed her lips and nodded. "Go ahead."

I pulled a Tshirt and jeans out of the closet and went into the bathroom. Robert Johnson peeped out the side of the shower curtain.

"Not yet," I told him.

His head disappeared back into the bathtub.

I'd just taken off the dress shirt and was pulling the sleeves rightside out when Allison came in and poked her finger in my back, touching the scar above my kidney.

It took great effort to control my backward elbow strike reflex.

"What's this?" she asked.

"You mind not doing that?"

She acted like she hadn't heard. She poked the scar again, like the puffiness of the skin fascinated her. Her breath dragged across my shoulder like the edge of a washcloth.

"Bullet hole?"

I turned to face her, but there wasn't much place to back up unless I sat in the sink.

"Sword tip. My sifu got a little excited one time."

"Sifu?"

"Teacher. The guy who trained me in tai chi."

She laughed. "Your own teacher stabbed you? He must not be very good."

"He's very good. The problem was he thought I was good too."

"You've got another scar. That one's longer."

She was looking at my chest now, where a hash dealer had stabbed me with a Balinese knife in San Francisco's Tenderloin District. I put on my Tshirt.

Allison pouted. "Show's over?"

I waved her out and closed the bathroom door in her face. She was still smiling when I did it.

Robert Johnson stared at me as I put on the jeans. He looked about as amused as I was.

"Maybe if we rush her," I suggested. "A twoflank approach."

His head disappeared again. So much for backup.

When I came into the living room Allison had opened another beer and relocated to the futon.

"This reminds me of my old place in Nashville," she said, studying the waterstained plaster on the ceiling. "God, that was bad."

"Thanks."

She looked at me, puzzled. "I just meant it's small. I was living on nothing for a while.

Kind of makes me nostalgic, you know?"

"The good old days," I said. "Before you married money."

She drank some beer. "Don't knock it, Tres. You know what the joke was in Falfurrias?"

"Falfurrias. That's where you're from?"

She nodded sourly. "We joked that you only go to college for an MRS." She tapped her wedding ring with her thumb. "I bypassed the degree plan."

She closed all ten fingers around the beer bottle and kicked her feet up on the futon. I stared at the beer, wondering how many it would take for me to catch up with her.

"When I was eighteen I was working during the summer as a secretary at A1 Garland's auto dealership." She looked at me meaningfully, like I should know A1 Garland, obviously a bigwig in Falfurrias. I shook my head. She looked disappointed.

"I was trying to sing at a few clubs in Corpus Christi on the weekends. Next thing I know A1 was telling me he was going to leave his wife for me, telling me he would finance my music career. We started taking weekend trips to Nashville so he could show me how rich and important he was. He must've sunk ten thousand into the wallet doctors."

"Wallet doctors?"

She grinned. "The guys in Nashville that smell smalltown money a mile off. They promised A1 all kinds of stuff for me—recordings, promotion, connections. Nothing ever happened except I showed A1 how grateful I was a lot. I thought it was love for a while. Eventually he decided I'd become too expensive. Or maybe his wife found out. I never knew which. I got left in Nashville with about fifty dollars in cash and some really nice negligees. Stupid, huh?"

I didn't say anything. Allison drank more beer.

"You know the bad part? I finally got up the courage to tell somebody in Nashville that story and it was Les SaintPierre. He just laughed. It happens a hundred times every month, he told me, the exact same way. The big trauma of my life was just another statistic. Then Les told me he could make it right and I got suckered again. I was a slow learner."

"You don't have to tell me any of this."

She shrugged. "I don't care."

She sounded like she'd said it so many times she could almost believe it.

"What happened with the agency?" I asked. "Why did Les decide to push you out of the business?"

Allison shrugged. "Les didn't want somebody bringing him back to earth when he went really far out with an idea. He didn't know when to stop. Most of the time, it turned out well for him that way. Not always."

"Such as?"

She shook her head, noncommittal. "It doesn't really matter. Not now."

"And if he doesn't come back?"

"I'll get the agency."

"You sound sure. You think you can keep it afloat without him?"

" I know. Les' reputation. Sure, it'll be tough, but that's assuming I keep the agency.

The name is worth money—

I can sell it to all kinds of competitors in Nashville. There are also contracts in place for publishing rights on some hits that are still bringing in money. Les wasn't stupid."

"Sounds like you've been looking into it."

Allison shrugged. Slight smile. "Wouldn't you?"

"You must've run down his assets, then."

"I've got a pretty good idea."

"You know anything about a cabin on Medina Lake?"

Allison's face got almost sober. She stared at me blankly. I told her about the probate settlement from Les' parents' property.

"First I've heard about it."

But there was something else going on in her head. Like something that had been bothering her slightly for a long time was now coming to the forefront. I looked at her, silently asking her to tell me about it. She wavered, then looked away. "You have a plan, sweetie?"

"I thought I'd head out there. Check things out."

I regretted my answer as soon as I said it.

Allison tottered to her feet, held up her beer to check how much was left, then smiled at me. "You'd better drive. I'll navigate."

Then she began that job by trying to locate the front door.

Allison was quiet for the first half of the trip.

She'd complained bitterly before we left about me making her a thermos of coffee rather than tequila, then making her change clothes into something more utilitarian. I'd found a pair of Carolaine's drawstring Banana Republics and a crewneck pullover in the back of the closet. They fit Allison well. Once we got going, she curled into the passenger's seat of my mother's Audi with her knees on the dash and her face behind the coffee mug and a pair of my mother's purple sunglasses she'd pulled out of the glove compartment. For a while she made occasional "uhh" sounds and I thought she was going to be ill, but once we got out of the city she began to perk up.

She even decided to come with me into the tax assessor's office when we got to Wilming. Wilming was a small county seat consisting of an American Legion Hall and a Dairy Queen and not much else. The assessor's office was open Saturday because it was also the post office and the grocery store. After successfully scoring the deed and the last five years of tax records on Les' property I had to grudgingly admit that having the subject's wife with me, the subject's pretty blond wife, had helped expedite matters somewhat.

When we got back in the car Allison poured herself more coffee and said, "Gaah."

"It's just strong," I said. "You're not used to Peet's."

She shuddered. "Is this like Starbucks or something?"

"Peet's is to Starbucks what Plato is to Socrates. You'll appreciate it in time."

Allison stared at me for about half a mile, then decided to turn her attention back to the tax assessor's documents and the coffee.

She flipped through the paperwork on Les' cabin. "Bastard. Two years ago he changed the billing for the tax statements so they wouldn't come to the house. Exactly when we got married."

"He wanted a place you didn't know about. He might've already been thinking about getting away someday, leaving himself an exit route."

She made a small, incredulous laugh. "What's this billing address in Austin? A girlfriend?"

"Probably a mail drop. A girlfriend would be too risky."

"Bastard. You think you can find this place?"

I shook my head. "Don't know."

We had the exact address for the cabin but that didn't mean much at the lake. Most people had their address registered as a mailbox along the main highway, and there would be hundreds of those, all plain silver, many of them with incomplete or weathereddown numbers. Even if we found the right box it wouldn't necessarily be near the cabin. Most likely that would be a mile or two down some unnamed gravel road, the turnoff marked only by wooden boards displaying the last names of some of the families that lived that way. Often there was no sign at all, no way to find someone out here unless you had wordofmouth instructions. If you could avoid the notice of the locals, Medina Lake wasn't a bad place for a missing person to hide out.

We passed Woman Hollow Creek, wended our way through some more hills, down Highway 16. The ratio of RVs to cars began to climb.

Allison examined my mother's medicine pouch on the rearview mirror, letting the beads and feathers slip through her fingers. "So how do you know Milo anyway? You two don't seem—I don't know, you're like the Odd Couple or something."

"You know that scar on my chest?"

Allison hesitated. "You're kidding."

"Milo didn't do it. He had this idea. He thought I'd make a good private detective."

The road was too twisty for me to look at Allison's face, but she stayed quiet for another mile or so, the purple sunglasses turned toward me. I missed the noise and the wind and rattling of the VW. In my mother's Audi, the quiet spaces were way too quiet.

Finally Allison laced her fingers together and stretched her arms. "Okay. So what happened?"

"Milo was assistant counsel for defence on this homicide case. His first big job with Terrence 8c Goldman in San Francisco. He wanted someone who could track down a witness—a drug dealer who'd seen the murder. Milo thought I could do it. He thought he'd really impress his boss that way."

"And you found the guy."

"Oh, yeah, I found him. I spent a few days in San Francisco General afterward."

"Milo's boss was impressed?"

"With Milo, no. With me, yes. Once I got out of intensive care."

Allison laughed. "He gave you a job?"

"She. She offered to train me, yes. She fired Milo."

"That's even better. And a woman, too."

"Most definitely a woman."

Allison opened her mouth, then began to nod. "Ah ha. Milo wanted to impress—"

"It wasn't just professional."

"But you and her—"

"Yeah."

Allison grinned. She nudged my arm. "I do believe the P.I. is blushing."

"Nonsense."

She laughed, then uncapped the thermos and poured herself another cup of Peet's.

"This stuff is beginning to taste better."

We skirted the lake for over a mile before we actually saw it. The hills and the cedars obscured the view most of the way around. The waterline was so far down that the clay and limestone shore looked like a beige bathtub ring between the water and the trees.

Medina wasn't a lake you could get your bearings on very easily. The water snaked around, following the course of the original river that was dammed to make the lake, etching out coves and dead ends, each outlet and inlet looking pretty much like all the others. We might've been searching for Les' cabin the rest of the week if an old friend hadn't helped us out.

37

About a mile past the Highwaycutoff, a black Ford Festiva was pulled off on the right side of the road, opposite the lake. The driver's side window was open and a redheaded orangutanlooking guy was behind the wheel, reading a newspaper.

I drove a quarter mile up the road and then Ued around. I waited for a semi to rumble by and then pulled in behind it, following close.

"What are we doing?" Allison asked.

"Keep looking straight ahead."

On my second pass the redhead in the Festiva still didn't pay me any attention, but it was definitely Elgin. He had his head firmly buried in the sports page. Advanced surveillance methods. He'd probably figure out to poke eyeholes in the paper pretty soon.

I quickly scanned the area he was staking out. There were no side roads in view.

There were no mailboxes. It was just a curve of highway around a hill. On the lake side the road fell away in a steep, heavily wooded slope, so you couldn't really see what was down toward the water, but there were some power lines angling in. That meant at least one cabin and only one way to get down there—past Elgin.

"Elgin without Frank," I said. "Not smart."

Allison looked behind us. "What are you talking about?"

I told her about my encounter the night before with Elgin and Frank on the side of the highway, how they'd introduced my face to the asphalt and offered me a very nice throwdown gun. I told her they were probably sheriff deputies, buddies of Tilden Sheckly.

"What shits," she said. "And they're watching Les' place?"

"One of them at least."

"So we're going to go back and whack him on the head or something, right? Tie him up?"

I chanced a look sideways to see if she was kidding. I couldn't tell. "Whack him on the head?"

"Hey, I've got Mace, too. Let's go."

After her performance with Sheckly the previous evening I thought it prudent not to deride her abilities as a headwhacker. I said, "Let's keep that as a backup plan. Get a fifty out of my backpack."

We kept driving, going back as far as Turk's Ice House.

After five minutes of chitchat with Eustice, the blue haired store clerk in the flashy satin shirt, we came to an agreement that the cove we wanted was Maple End and no, Eustice didn't recognize Les from his picture and no, Allison hadn't gone to high school with Eustice's daughter. Despite the last disappointment, Eustice agreed to introduce us to Bip, who agreed to loan us his outboard fishing boat for fifty dollars. Bip and his boat were both large grayish wedges, dented up and grungy, and both smelled like live bait. Bip kept grinning at Allison and saying "whuh!" every time he looked away from her.

I tried to give him warning looks, to let him know he was putting himself in mortal peril, but Bip paid no attention.

We started the outboard with some effort and pulled away from the dock at Turk's.

The cove widened into the main spine of the lake. A half mile away, on the far shore, the hills were dotted with cabins and radio towers. Occasionally a motorboat would zip by a few hundred yards away; a minute or so afterward we'd find ourselves bobbing up and down as we cut through the wake. By the time we'd turned the boat toward the mouth of Maple End Cove we had lake water up to our ankles and I'd had to move my backpack off the floor and into my lap. Bip had assured us those little holes in the boat would be no problem.

Allison took off her shoes and was about to dangle her footsies over the side when I said, "I wouldn't do that."

She frowned. In the afternoon sun, the purple glasses cast long red reflections down her cheeks. "What? They're already wet."

"It's not the water. It's the moccasins."

I pointed ahead to a spot where the water was rippling a little bit more aggressively than the normal dips and swells.

Allison brought her feet back in.

We passed the floating nest. A dozen or so green and silver whips were twisting into sailor's knots just below the surface.

Allison whistled softly. "Only snakes we had in Falfurrias got made into belts. Hope these guys understand if the boat sinks next to them."

"Me too. Last year a waterskier took a spill into one of those nests. She died instantly."

Allison put her feet up on my bench, one on either side of my legs. Her toenails were painted red. Her pants legs were rolled halfway up her tan calves and fit tight that way, not loose as they would've on Carolaine.

She rested her elbow on her knee and cupped her hand on her chin and blinked her eyes at me. "I believe you made that up, Mr. Navarre."

I shrugged, tried not to smile. We puttered along past the snakes.

The southern tip of Maple End Cove, sure enough, had a huge maple tree jutting from the top of the ridge. Maples are pretty rare in Texas, but this one apparently hadn't heard the news that it wasn't supposed to thrive. It was at least thirty feet tall and blazing with fall colours. The rocky ground around it was littered with burnt orange and apple yellow. At the waterline below, several women were sunbathing on an old floating pontoon dock. There were stairs cut into the rock, leading down to the dock, but they stopped a good twenty feet above, where the waterline used to be.

The cove narrowed quickly as our boat puttered into it. After one curve the banks on either side were no more than twenty yards apart. The water this far back was murky green and smelled of stagnation—scum and leaking septic material and dead fish. The shoreline on the right was fairly steep and thick with cedars and live oaks, all the branches overgrown with spiky Spanish moss. I could glimpse the tops of semis or RVs speeding along the highway above where Elgin was parked.

There were two cabins, both on that side of the cove. The one farther down was a wellkept whiteshingled house set almost at the top of the ridge. At the water level was a floating dock, and above that a small patch of lawn grass. A handpainted wooden sign meant to be read from the water proudly announced: THE HEIDEL MANS, with daisies and frogs all around the letters. There was a small army of plastic waterfowl with wind propellers for wings surrounding the sign and a flagstone path up to the house. The windows were all shuttered and no lights were on.

A half acre closer to us was a militarystyle Quonset hut that jutted out of the slope about halfway between the water and the highway. It had a wooden deck facing the water. The front wall was painted chocolate brown, with a screen door and two windows covered in yellow curtains. The hut's shell was an arc of corrugated aluminium as dull as the inside of a food can. There was a metal pipe chimney in the back.

"My husband," Allison sighed. "Wonder if I can figure out which one of these is his."

I cut the boat's engine and drifted into the tall weeds by the shore below the Quonset hut. The boat ground against the rocks as it came to a stop.

There was a dock, sort of. The cement pylons were still there, and a few boards not yet rotted to splinters. I wasn't sure I wanted to trust them with my weight.

Ten feet to the left of the dock there was a sunken boat sticking its prow out of the water. The remnants of Bip's last customer, maybe.

I sloshed and slipped my way onto dry land. Allison stayed right behind me. I looked up at the dark windows and the closed door of the Quonset hut.

If Elgin was smart, if he was keeping watch because he thought Les might show up here, he'd have his partner Frank somewhere down here. Maybe at the Heidelmans, or even inside Les' cabin. Of course if Elgin was smart, he wouldn't have been so damn easy to spot on the highway. I figured we had a fighting chance.

We climbed what passed for steps—old boards hammered perpendicularly into the clay of the hill. The stairs to the deck were on the side of the cabin. Nobody on the highway could've seen us from there. Nobody jumped out of the woods in commando gear. We made plenty of creaks and cracks getting to the front door. If anybody was inside, they'd sure as hell know we were coming.

The door was padlocked—one of those loops slotted through a metal hinge. Dumb.

I got Allison to hand me a Phillips head out of my backpack and removed the base of the hinge in less than a minute. We could've gone through the window pretty easily too, but I wasn't ready to break glass just yet.

We went inside the hut.

Allison said, "Yuck."

It was dark. It smelled like rotten food and sour laundry. In the light of my pencil flashlight it was difficult to piece together exactly what we were seeing, what happened here. There was an unmade single bed against the left wall. A portable stereo against the right littered all around with CDs and cassettes. The CD carriage was sticking out—the "drink holder," as my brother Garrett called it. The floor was covered in grass mat that was starting to tear into separate squares. The curved roof was covered with black cloth that just made the space seem more claustrophobic. In the back was a kitchenette and a phone and one shuttered window and a tiny walledin area that must've been the bathroom.

When our eyes adjusted to the dark Allison went into the kitchen and lifted a pan of halfscrambled eggs from the electric grill. They were rubberized in places, crystallized in others.

"Two eggs for breakfast," Allison said. "Every day, no exceptions."

"He left halfway through making those," I said. "What do you think—about two or three days ago?"

Allison shuddered, put the pan down. "Something like that. So the bastard's alive."

She sounded less than thrilled. She gave me a tentative smile. "I guess I figured that.

It's just—"

She hooked her thumbs in her borrowed Banana Republics, looked around at her feet where men's clothes were strewn around as if somebody had walked through a laundry pile. Then she kicked one of Les' shirts with a vengeance.

I went into the bathroom. A man's toiletry bag was in the sink, next to a propanepowered Destroilet with directions on the lid about how to avoid a house fire when you flushed.

I got out my Polaroid and took a picture of the toilet. Nobody would believe me about it, otherwise. Then I took some pictures of the rest of the cabin—the eggs, the laundry, the scattered CDs.

I went to the kitchen counter and picked up the phone. The line was active. I set the switch from touch tone to pulse and pressed redial. I was pretty sure I got the number on the first listen but I hung up before it rang, then tried it again. I wrote the number on my hand and let the phone ring. No answer on ten, no answering machine.

Allison said, "Tres."

I turned. She was looking at me reproachfully, holding the frying pan with the eggs. As quietly as possible she said, "Well? This or the Mace?"

"Wha—"

Then I heard the creaking, from outside, like someone trying to climb the old porch steps with at least some semblance of stealth.