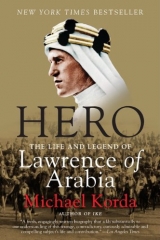

Текст книги "Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia "

Автор книги: Michael Korda

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 55 страниц)

Close as was the relationship between Lawrence and Feisal, Lawrence’s intense admiration for Auda is a constant theme in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, not surprisingly, since they had many traits in common: physical courage, hardiness, cool judgment under fire, indifference to danger, a flamboyant gift for the theatrical side of warfare, and a magnetic attraction that drew hero-worshippers to them and made them natural leaders. Auda was the more bloodthirsty of the two; he reveled in killing his enemies, and had been known in his younger days to cut out the heart of someone he had killed and take a bite out of it while it was still beating—though, as James Barr points out in Setting the Desert on Fire, in that respect Auda was merely an old-fashioned traditionalist, since this had been, in the good old days, an accepted custom in desert blood feuds.

Lawrence’s description of Feisal’s camp at Wejh during February and early March 1917 makes it clear that the majority of his men were doing nothing except lounge around, while Feisal sought to resolve blood feuds and to win the loyalty (or at least the neutrality) of the sheikhs of the tribes and clans to the north. This involved endless negotiations and the exchange of “presents,” which in practice meant payment in gold sovereigns, and promises of more to come. The British supplied the gold, andalso, to the great amusement of the Arabs, two armored cars, and a variety of other vehicles, as well as drivers from the Army Service Corps, and a naval wireless station powered by a generator. The encampment was spread out and enormous, since each tribe and clan wanted its tents to be as far away from the others as possible, and included at its center a tented bazaar, or marketplace. Lawrence made a point of walking everywhere barefoot, so as to toughen the soles of his feet. He lived in comparative opulence in Feisal’s camp, on a raised “coral shelf” about a mile from the sea, where Feisal maintained “living tents, reception tents, staff tents, guest tents,” and the tents of the numerous servants. It was not only with gold and honeyed words that Feisal sought to impress the tribal leaders, but also with his impressive surroundings, as befitted a prince and a son of the sharif of Mecca. The number and size of his tents, the layers of priceless carpets, and the endless banquets—these were all necessary accompaniments if he was to move his army north toward Damascus.

For the moment, neither Jaafar’s “regulars” nor Auda’s tribesmen had much to do. Such action as was taking place consisted largely of raids inland to damage the railway line to Medina, and these were carried out by Newcombe, Garland, and Lawrence, accompanied by small numbers of tribesmen to engage the Turks if they appeared. The Turks were determined to repair the railway line whenever it was broken—and since the line had originally been intended to run all the way to Mecca, they had no shortage of rails stored in Medina with which to repair it.

Medina continued to be the focus of everybody’s attention. The Turks were determined to hold on to it; the army of Abdulla was ensconced to the north of the city in Wadi Ais; Feisal still harbored thoughts of advancing from Wejh to attack it in collaboration with Abdulla; Colonel Brйmond was being urged on by cables from Paris to persuade the Arabs to attack Medina at once. Early in March, the partial interception of a message from Jemal Pasha to Fakhri Pasha, which seemed to call for the evacuation of Medina and the transfer of the troops there to Gaza and Beersheba, set off a panic. General Murray, in Cairo, had been informed it was Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s personal wish that he shouldattack Gaza again, and he was preparing to do so with some reluctance, since he was also warned at the same time not to expect any additional troops, and even that he might have to send more of his units to France. The addition of two or three more Turkish divisions on the Gaza-Beersheba line would almost certainly prevent an attack, so it became imperative that either Medina should be taken, or the railway should be cut off once and for all so no Turkish troops could be transferred north.

Since his nominal superior Colonel Newcombe was away dynamiting railway tracks, Lawrence decided to ride from Wejh to Wadi Ais to inform Abdulla of what was happening—and, perhaps more important, what was expected of him, since, in Lawrence’s words, “he had done nothing against the Turks for the past two months.” Lawrence was ill with dysentery, “feeling very unfit for a long march,” but despite this he set off, with Feisal’s approval and a handpicked escort of tribesmen, for Wadi Ais, a distance of about 100 miles as the crow flies, but more on the ground. His traveling party might have made him feel uneasy had he not been too sick to think about it, since it was ill-assorted, consisting of men from different tribes. He was unable to ride more than four or five hours at a stretch; the pools of water and the few wells on the way had turned salty, a cause for some concern; boils on his back were giving him considerable pain when he rode; and the landscape, which was rugged, hilly, and flinty, made it necessary from time to time to dismount and walk the camels up zigzagging slippery trails of worn stone. In the distance, huge and fantastic rock formations loomed. Finally, the landscape changed: there was grass for the camels in a narrow valley, and the men camped for the night under the lee of a “steep broken granite” cliff. Lawrence was suffering from a headache, a high fever, occasional fainting fits, and attacks of dysentery that left him light-headed and exhausted.

He was woken by a shot, but thought nothing of it at first, since there was game in the valley; then one of the party roused him and led him to a hollow in the cliff, where the body of one of the Ageyl camel men lay. The man had been shot in the head, at close range. After some initial confusion and discussion of the ethics of blood feuds, it was agreed thathe had been shot by another of the party, Hamed the Moor, following a brief quarrel between them. Lawrence crawled back to where he had been lying, beside the baggage, “feeling that this need not have happened this day of all days when I was in pain.” A noise made him open his eyes, and he saw Hamed, who had put his rifle down to pick up his saddlebags, no doubt preparing to run away. Lawrence drew his pistol, and Hamed confessed to the murder. At this point the others arrived, and the Ageyl’s fellow tribesmen demanded, as was their right, blood for blood. Lawrence, whose head was pounding, gave some thought to this. There were many Moors in the army, descendants of Moroccans who had fled to the Hejaz when the French took over their country, and if the remaining two Ageyl shot Hamed there would inevitably be a blood feud between the Moors and the Ageyl. Lawrence decided that as a stranger, a non-Muslim, and a man without a family, he could execute the Moor without creating a blood feud that might spread through the army. His traveling companions, after some discussion, agreed.

He marched Hamed at gunpoint into a narrow crevice in the cliff, “and gave him a few moments’ delay, which he spent crying on the ground,” then “made him rise and shot him through the chest.” Hamed fell to the ground, but was still alive and “shrieking,” as blood spurted from his wound, so Lawrence shot him again. By that time, Lawrence’s hand was shaking so badly that the bullet struck the dying man only in the wrist. Lawrence regained control of himself, moved closer, put the muzzle of his pistol to Hamed’s neck, under the jaw, and pulled the trigger.

That did it. The remaining Ageyl, for whose benefit Lawrence had carried out the execution, buried Hamed’s body, and after a sleepless night Lawrence was so ill that they had to lift him up into his saddle at daybreak.

Lawrence devotes only four paragraphs to Hamed’s execution in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, and some of his biographers give the incident less space or even leave it out altogether; but despite the brevity, the obvious restraint, and the total lack of self-pity, his account clearly represents a turning point in the life of the former Oxford archaeologist and aestheteturned mapmaker and intelligence officer. He does not mention it again, perhaps because—as with so many things that happen in war—leaving it behind and moving on seemed more sensible. The prose in which Lawrence describes the experience, despite a tendency toward a certain florid and archaic quality when he is trying too hard to create the literary masterpiece that he hoped would take its place beside such great books as Moby-Dick, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and The Brothers Karamazov, is in this instance notably spare and lean. Indeed it is one of the places in Seven Pillars of Wisdom where Lawrence succeeds in striking exactly the tone that Ernest Hemingway spent his life perfecting: a shocking event is described in the bare minimum of words, and with no attempt to convey Lawrence’s feelings at killing another human being at close range. It is unlikely that he had none, but whatever they may have been, he does not share them with the reader. In the words of W. B. Yeats, he “cast a cold eye on life, on death,” and passed by.

Perhaps his own illness, and the greater importance in the grand scheme of things of reaching Emir Abdulla as soon as possible with the message about Medina (which, ironically, turned out to be false), helped Lawrence to put the incident out of his mind. But whatever the case, Hamed’s death marks the point at which Lawrence gave up the moral comfort of being a liaison officer, observing events from a distance, and transformed himself into a man of action, leading other men, sometimes to their death; killing Turks when he had to kill them; exposing himself to danger with a lack of fear, or even of caution, that astonished both the Bedouin and the British; and accepting unthinkable pain without complaint.

Shock finally set in, for Lawrence’s description of the next two days of his journey to Wadi Ais has a quality of desert hallucination. His meticulous description of the landscape conveys in its wealth of details a cumulative horror, which reaches a peak when during a rest he throws a rock at one of the party’s camels in disgust at its self-satisfied mastication. At one point Lawrence’s party stumbles across a Bedouin encampment and instead of letting him sleep outside, his host—"with the reckless equality” and hospitality “of desert men"—insists that Lawrence share his tent, so that Lawrence leaves in the morning with his “clothes stinging-full of fiery points feeding on us,” because of the lice and fleas. on the third day, crossing a “broken river of lava,” one of his camels breaks a leg in a pothole—the bones strewn around are mute testimony to the frequency with which this occurs—and Lawrence feels so sick that he fears some well-meaning tribesman will try to cure him, for the only method the Bedouin know is to burn a hole or holes in the patient’s body in a spot which is assumed to be opposite the site of the illness, a treatment often more painful than the disease, or to have a boy urinate into the wound.

At last he found Abdulla, in the process of setting up a new camp in a pleasant grove of acacia trees—as was always the case with Bedouin camps, the men and animals had fouled the old one by paying no attention at all to sanitary arrangements. Lawrence handed over the letters he had been carrying from Feisal, and explained the problem of Medina to Abdulla in his luxurious tent, although Abdulla did not seem much disturbed by or interested in it. Then, Lawrence collapsed in the adjacent tent that was pitched for him.

Lawrence spent about ten days in his tent “suffering a bodily weakness that made my animal self crawl away and hide till the shame was passed.” This surely refers to dysentery, a common enough illness among Europeans living with the Bedouin and unaccustomed to tainted water and unhygienic surroundings. Lawrence’s symptoms may also have been intensified by some degree of what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder, brought about by the execution of Hamed. In any event, for ten days he rested and tried to recuperate in his stifling tent, drowsing, plagued by flies, and thinking about military strategy. Eventually, he came to the conclusion that any attempt to take Medina would be a mistake. As Lawrence himself put it, he “woke out of a hot sleep, running with sweat and pricking with flies, and wondered what on earth was the good of Medina to us?” In Colonel Lawrence, Liddell Hart bases his claim for Lawrence as a military genius on these sickbed musings in Abdulla’s camp. Indeed the conclusions that Lawrence reached about war, as he set them out in Seven Pillars of Wisdom five years later, define very well the kinds of warfare that big western armies found it so hard to win against through much of the twentieth century, and the first decade of the twenty-first. First of all, Lawrence reached the conclusion that in “irregular warfare” it made no sense to hold or to seize a specific point. The goal was to strike the enemy where he least expected to be attacked, then vanish back into the desert, and to avoid, so far as possible, big battles in which the enemy could put to use his superior firepower and military discipline.

The object, he decided, should be to keep the Turks bottled up in Medina, where they could do no harm, and therefore to restrict, not cut, the railway that was their only line of communication with the rest of the Turkish army. Half-starved and reduced to eating their own transport animals, which were useless to them without forage, the Turks would no longer present a serious danger to Mecca, and could be reduced to exhaustion and impotence by frequent attacks on the railway, which they would constantly have to repair and defend—they would, in fact, be “all flanks and no front.” once Lawrence rose from his sickbed, he had a simple strategy for beating the Turks, not by fighting battles to take the fortresses and towns they held, but by destroying what they could neither easily replace nor defend: locomotives, railway cars, telegraph wires, bridges, and culverts. The Turks would have to spread themselves thin to defend these targets, and it would then be easier to attack and kill small Turkish parties. In short, a war of mobility was needed, a war in which the Arabs would use to the full their possession of camels and the protection of the desert in order to appear where they were least expected, and not anchor themselves in Wejh—or for that matter in Wadi Ais, where Abdulla was making himself too comfortable for Lawrence’s taste.

TURKEY’S LIFELINE

When Lawrence was well enough to stand, he went to Abdulla’s great tent and explained his plans, without eliciting any enthusiasm from Abdulla, who was no more anxious to blow up the railway than he was to attack Medina. A cultivated man who enjoyed poetry and hunting, he had come to Wadi Ais at his brother Feisal’s request, but having reached it and made himself comfortable, he was not about to be prodded into action, least of all by Lawrence, whom he disliked. However, recognizing in Lawrence a reflection of Feisal’s more spirited view of the war (as well as an altogether superior will), he allowed Lawrence to gather a group of his tribesmen, a quantity of explosives, two of the antiquated mountain guns Abdulla had received from General Wingate in Khartoum, and a German Maxim machine gun on a sledge drawn by a long-suffering donkey, and to go out to put his ideas into practice. Abdulla’s cousin Sharif Shakir, an altogether more warlike figure, promised to collect a force of 800 fighting men, to attack whatever Lawrence liked.

On March 26, Lawrence and his advance party of thirty men rode off down Wadi Ais and undertook a three-day march across the desert to a600-foot hill of sand that overlooked the railway station at Aba el Naam. It consisted of two buildings and a water tank, and like most of the Turkish stations, was as stoutly built of stone as a fortress, and garrisoned by nearly 400 troops; but also, like most of them, it had the disadvantage of being surrounded by higher ground, since any railway must be laid when possible on flat ground, and take advantage of valleys. Lawrence was therefore able to approach very close to the station without being seen. Shakir turned up as night fell, but with only 300 men instead of the 800 he had promised; as Lawrence soon discovered, any Arab promises of numbers were best taken with a grain of salt. Still, he was determined to go ahead, and rode on in the dark to the south of the station, where, for the first time in the war, he “fingered the rails … thrillingly,” and planted “twenty pounds of blasting gelatine” under the track, with one of Garland’s improvised trigger fuses, made from the lockwork of an old British army single-shot Martini rifle, with the trigger exposed so that pressure would release it. He put his two guns in position, and placed the Maxim to kill the locomotive’s crew, if they survived the explosion. At daybreak, he started shelling the station, doing considerable damage, especially to the all-important water tank. The crew of the locomotive uncoupled it from the train and began to back it southward toward safety until it ran over the mine and vanished in a cloud of sand and smoke. Although Lawrence’s Maxim gunners had apparently lost interest or patience and abandoned their post, in this first effort thirty Turkish prisoners were taken, and about seventy Turks were killed or wounded; nine more were killed when they tried to surrender and the Arabs shot them anyway. The station and the train caught fire, the locomotive was seriously damaged, and a part of the track was destroyed. For three days all traffic to and from Medina was stopped. Only one of Lawrence’s Bedouin was slightly hurt, so the attack demonstrated his theory about inflicting the maximum damage with the minimum of losses.

Lawrence’s detractors, then and now, still argue that this was merely a “pinprick,” in “a sideshow of a sideshow” compared with the western front, but it in fact was a modest first effort at a new kind of warfare—inwhich an organized, modern, occupying army was forced to deal with small but lethal attacks by an enemy who appeared suddenly out of nowhere, struck hard, and vanished again; in which the ambush, the roadside or railway “improvised explosive device,” the grenade thrown onto a busy cafй terrace, the destruction of rolling stock, even the “suicide bomber,” would take the place of battle; and in which it was almost impossible to distinguish enemy combatants from the surrounding civilian population.

Lawrence rode back to Abdulla’s camp, where a huge celebration took place, and set off the next morning with about forty tribesmen and a machine gun platoon to mine the tracks again. He seems to have regained his health and equilibrium. Mechanical devices and gadgets, whether in the form of bombs, fuses, cameras, or motorcycles, always seemed to cheer Lawrence up, even at the worst of times, and his description of the landscape is, as always, detailed and fascinating. He had the gifts of a great nature writer and presents with a kind of detached objectivity the hardships of desert travel: a fierce sandstorm, which sends pebbles and whole small trees flying at his party like projectiles, followed by heavy rain and a sudden drop in the temperature that leaves him and his party shivering. The wind is so strong that Lawrence’s robes get in his way as he climbs a rocky crag, so he strips and makes his way naked up the sharp, slippery rocks—one of the servants falls headfirst to his death—and finally arrives at kilometer 1,121 (measured from Damascus) of the railway at ten at night, close to a small station with a Turkish garrison.

Lawrence was eager to experiment with a more complicated mine; its trigger would fire two separate charges at the same time, placed about ninety feet apart. It took him four hours to lay the mine; then he crawled back to “a safe distance” to wait for dawn. “The cold was intense,” he wrote later, “and our teeth chattered, and we trembled and hissed involuntarily, while our hands drew in like claws.” Only the day before, the heat had been so oppressive that Lawrence had been unable to walk barefoot, to the amusement of the tribesmen “whose thick soles were proof even against slow fire.” It is worth noting that the desert provides everykind of torment—heat, cold, rain, flash floods, windstorms, biting insects, and sandstorms, sometimes all on the same day.

At dawn a trolley with four men and a sergeant passes over the mine, but luckily it is too light to set off the explosive—Lawrence doesn’t want to waste his explosives and firing mechanism on so small a target. Later a patrol of Turkish soldiers on foot examines the area around the mine—it has been impossible to hide the tracks because the rain has turned the sand to mud—but finds nothing; then, a heavy train, fully loaded with civilians, many of them women and children, being evacuated from Medina runs over the mine but fails to explode it, infuriating the “artist” in Lawrence—he has already begun to think of demolition as a kind of art form—but relieving “the commander” and, more important, the human being, who has no wish to kill women and children. By now the Turkish garrison is aware of the presence of Lawrence and the others, and opens fire from a distance; Lawrence and his men hide until nightfall. Then he makes his way back to kilometer 1,121 and slowly, carefully, with infinite caution feels up and down the line in the dark for the buried hair trigger, finds it, and raises it one-sixteenth of an inch higher. Afterward, to confuse the Turks, Lawrence and his men blow up a small railway bridge, cut about 200 rails, and destroy the telegraph and telephone lines, then head for home, having already sent on ahead of them the machine gunners and their donkey. The next morning, they hear a great explosion, and learn from a scout left behind that a locomotive with trucks of spare rails and a gang of laborers set off the mine in front of it and behind it, effectively blocking the track for days.

Quite apart from his boyish excitement at blowing things up—one of Lawrence’s endearing qualities is a kind of innocent delight in pyrotechnics, and throughout his life he retained some of the more attractive characteristics of an adolescent—Lawrence had every reason to be pleased. He had blocked the line to Medina for days, and rendered Turkish troops all the way up and down the line nervous and on full alert, at the cost of a little blasting gelatine and the accidental death of one servant with a fear of heights.

Lawrence could easily imagine the effect of doing this on a grand scale, and he was eager to get away from Abdulla, whose generosity did not compensate in Lawrence’s eyes for his lack of fighting spirit.

Each of them misjudged the other. When Abdulla fought, he fought well—he had led the force that captured Taif, the summer resort of Mecca, in the autumn of 1916 and took more than 4,000 Turkish prisoners, the only real victory of the Arab forces to date—and in some ways he was a better leader than Feisal, more flexible, and with a superficial layer of charm, worldly wisdom, and good humor that would keep him on his throne in Amman for over thirty years once Lawrence had helped him secure it. As for Lawrence, Abdulla’s distrust of him as a subversive British agent was unfounded—in fact, Lawrence wanted more for the Hashemite family than they were able to manage, and would use his status as a hero again and again in their support. No doubt Abdulla and his brothers resented the way Lawrence took the limelight—as he still does take it—in the world’s view of the Arab Revolt, but in the end Abdulla and Feisal would never have had their thrones without his help, and their victory was in part his invention.

Lawrence rode back to Wejh, changed his travel-stained clothing, and went immediately to pay his respects to Feisal, happy, one senses, to be back in a more martial atmosphere. His arrival coincided with that of Auda Abu Tayi and Auda’s eleven-year-old son Mohammed—Auda’s entrance into Feisal’s tent is in fact one of the best set pieces of Seven Pillars of Wisdom: “I was about to take my leave when Suleiman the guest-master hurried in and whispered to Feisal, who turned to me with shining eyes, trying to be calm, and said ‘Auda is here.’ I shouted, ‘Auda Abu Tayi,’ and at that moment the tent-flap was drawn back and a deep voice boomed salutations to our lord, the Commander of the Faithful: and there entered a tall strong figure with a haggard face, passionate and tragic…. Feisal had sprung to his feet. Auda caught his hand and kissed it warmly, and they drew aside a pace or two, and looked at each other: a splendid pair, as unlike as possible, but typical of much that was bestin Arabia, Feisal the prophet, and Auda the warrior, each looking his part to perfection.”

Lawrence saw in Auda the means of taking Aqaba, and moving the Arab Revolt north into Syria—for Auda was the preeminent desert warrior of his time, who could never be satisfied just with blowing up sections of railway track: his mind was set on a fast-moving war of sudden raids; he “saw life as a saga,” in which he was determined to be at the center. A visit to the English part of the camp, laid out in neat lines near the beach, was enough to warn Lawrence that the British were still determined to push the Arabs into attacking Medina, an objective that he had already concluded was probably impossible, and in any case pointless. Confident that the railway destruction could be continued in his absence, he returned to Feisal’s encampment and began to talk with Auda about the best way to move north, raise the Howeitat and some of the smaller tribes, and attack Aqaba from the direction the Turks would least expect. Auda, who had a natural sense of strategy, was enthusiastic; and Feisal, better than anyone else, understood the enormous importance of an unexpected Arab victory won without the help of the British—or even without their knowledge, for Lawrence had already made up his mind to take Aqaba as a kind “private venture,” drawing on Feisal for men, camels, and money.

Lawrence’s time at Wejh was marked by many warning signs that his own plans and those of his superiors were beginning to diverge sharply. He was in Wejh for just over three weeks, from April 14, 1917, to May 9, a period during which it was becomingly increasingly clear to Feisal that the French intended to claim Lebanon and Syria for themselves after the war, and that it suited them and to a lesser degree the British to direct the Arab armies toward taking Medina, rather than moving north into Syria and Palestine. During this period Sir Mark Sykes paid two short visits to Wejh. The first visit was to meet with Feisal while Lawrence was away; he had tried to present the content of the Sykes-Picot agreement to Feisal in the vaguest and most benevolent terms, without revealing that the British, French, and Russians had already agreed on a map that divided up the Ottoman Empire among them and excluded the Arabs from most ofthe cities and areas the Arabs wanted. Charming though Sykes was, the effect of his vagueness about details was to heighten rather than decrease Feisal’s shrewd and well-informed suspicions about Anglo-French policy in the Near East. Sykes returned to Wejh after a journey to Jidda for an even more trying and difficult meeting with Feisal’s father; and on May 7, accompanied by Colonel Wilson, he met with Lawrence, who, like most of the British officers in the Hejaz, now including even Wilson himself, strongly objected to urging the Arabs to fight while at the same time negotiating “behind their backs.” Lawrence was particularly outspoken on this subject, and it clearly played a role in his decision “to go [his] own way,” and ride deep into Syria with Auda, then take Aqaba from the undefended east.

He wrote an apologetic letter to General Clayton in Cairo. Then, without receiving orders or even bothering to inform his superior officers—he took advantage of the fact that Newcombe, who would certainly have tried to talk him out of it, was away attacking the railroad—Lawrence left with his Arab followers.

Lawrence’s many critics in later years have tried to belittle the risk of what he was proposing to do, but in fact it was a daring decision. Liddell Hart describes it as a “venture … in the true Elizabethan tradition—a privateer’s expedition,” across some of the harshest and most difficult terrain in the world, led by a man who already had a price on his head. It involved a desert march of more than 600 miles, a long “turning movement” that would take Lawrence to Damascus, then down through difficult terrain and unreliable tribes “to capture a trench within gunfire of our ships.”

Lawrence left Wejh early on May 9, with fewer than fifty tribesmen, accompanied by Auda Abu Tayi; Sharif Nasir, who would be Feisal’s spokesman to the tribes and the nominal commander; and Nesib el Bekri, a Syrian nationalist politician who hoped to make contact with Feisal’s supporters in the north. Lawrence took with him a train of baggage camels carrying ammunition; packs of blasting gelatine, fuses, and wire so hecould continue his demolition work; a “good” tent in which Nasir could receive visitors; sacks of rice, tea, and coffee for entertaining distinguished guests; and spare rifles to give away as presents. Each man carried on his own saddle forty-five pounds of flour intended to last him for six weeks, and the men shared among them the load of 22,000 gold sovereigns from Feisal’s treasury, weighing more than 800 pounds, to pay salaries and use where required as presents or bribes.