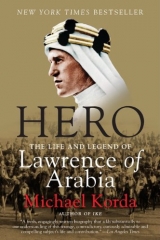

Текст книги "Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia "

Автор книги: Michael Korda

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 32 (всего у книги 55 страниц)

*Scipio’s decisive victory over Hasdrubal’s Carthaginians in Spain.

*Thirty thousand gold sovereigns would be worth about $9.6 million today.

*By the time the Kaiserschlact, as Field Marshal Hindenberg and General Ludendorff had named their offensive (thus shrewdly saddling the kaiser with the responsibility for it), ground to an end in June, it had cost the Germans nearly 700,000 casualties, and the British and French almost 500,000 each.

* Jeremy Wilson points out that Lawrence changed their names in Seven Pillars of Wisdom—they were actually Othman (Farraj) and Ali (Daud).

*From 1922, when Shaw first met him, Lawrence floats eerily into and out of Shaw’s plays: not only as Saint Joan, but elsewhere: as Private Meek in Too True to Be Good,and even as Adolphus Cusins, Barbara’s fiance in Major Barbara. Cusins is a slight,unassuming Greek scholar who in the end decides to become an armaments king, and hisdescription again might also serve for Lawrence: he is afflicted with a frivolous sense of humor … a most implacable, determined, tenacious, intolerant person who by mere force of character presents himself as and indeed actually is considerate,gentle, explanatory … capable possibly of murder, but not of cruelty or coarseness.(New York: random house, 1952, 228.)

*Even in the United Kingdom there was doubt. Asquith, the prime minister, noted in his diary on March 13, 1915, that “the only other partisan of this proposal [the Balfour Declaration] is Lloyd George who, i need not say, does not care a damn for the Jews or their past or their future.” (earl of oxford and Asquith, Memories and Reflections,1928.)

*There are conflicting accounts of Lawrence’s camel borne field library, but Liddell hart, who got the information from Lawrence himself, reports that he carried with him Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, the Oxford Book of English Verse, and the comedies of Aristophanes

* This is the same place as Abu el Lissal. Transliterations of Arabic place names into English were, and remain, idiosyncratic.

* A tender was an open car converted into the equivalent of what Americans call a pickup truck.

*his position was not unique. Captain J. r. Shakespear played much the same role toward ibn Saud on behalf of the government of india. When Shakespear was killed in a desert skirmish, he was replaced by St. John Philby, the noted Arabist, ornithologist,and convert to islam, and father of the master spy and traitor Kim Philby.

* Wavell meant, in modern terms, 12,000 cavalrymen, 57,000 infantrymen, and an artillery strength of 540 guns.

*These were the standard “bangers” of the British army. Lawrence occasionally ate meat, when it was a question of being polite to his Arab hosts, or when there was nothing else to eat but camel meat. on at least one occasion he expressed pleasure at a piece of gazelle roasted over an open fire. his vegetarian bent was not dogmatic

*The famous term describing non upper class usage that is, lower middle class and middle class usage that Nancy Mitford enshrined in the english language when she wrote “The english Aristocracy” for Encounter in 1954. Whatever else he was, Lawrence was an oxonian who spoke impeccable upper class english. The word “powwow”from a fellow officer would grate on his nerves as much as “serviette” for “napkin.”

*in his memoir, The Fire of Life, General Barrow asserts he had no such conversation with Lawrence, and that since indian cavalry regiments on the Northwest Frontier always had a certain number of riding camels attached to them, he was as familiar with camels as Lawrence was. on the otherhand, Barrow may not have realized only a fewhours after the scene between them at Deraa that Lawrence was pulling hisleg.

* To put this in perspective, the number of the brothers’ Algerian followers in and around Damascus may have been as high as 12,000 to 15,000 people (David Fromkin,A Peace to End All Peace, New York: holt, 1989, 336).

*Abd el Kader would eventually be shot by sharifian police outside his home in Damascus on September 3, 1919 a classic instance of the clich “shot while attempting to escape.” Mohammed Said lived on to become a supporter of French rule in Syria.

CHAPTER NINE

In the Great World

… that younger successor of Mohammed, Colonel Lawrence, the twenty-eight-year-old conqueror of Damascus, with his boyish face and almost constant smile—the most winning figure … of the whole Peace Conference. —James T. Shotwell, At the Paris Peace Conference Despite General Allenby’s abruptness, he and Lawrence had not lost their esteem for each other. Allenby may well have felt that Lawrence’s departure from Syria would make it easier for Feisal to get used to the inevitable, in the form of a French replacement, but if so he was wrong. Throughout the coming peace talks in Paris Lawrence would remain—to the fury of the French, and the occasional exasperation of the British Foreign Office—Feisal’s confidant, constant companion, interpreter, and adviser, the only European with whom Feisal could let his guard down. In Cairo, Lawrence gave Lady Allenby one of his most treasured mementos, the prayer rug from his first attack on a Turkish train. Allenby not only wrote to Clive Wigram,* assistant private secretary to King George V, asking him“to arrange for an audience with the King” for Lawrence, but at Lawrence’s request made him “a temporary, special and acting full colonel,” a rank that entitled Lawrence to take the fast train from Taranto to Paris instead of a slower troop train, and to have a sleeping berth on the journey. Allenby also wrote to the Foreign Office to say that Lawrence was on his way to London to present Feisal’s point of view on the subject of Syria.

Lawrence’s return therefore had a semiofficial gloss—far from coming home to shed his rank and be “demobilized,” in the military jargon of the day, Lawrence arrived with the crown and two stars of a colonel on his shoulders and a string of interviews arranged at the very highest level of government. Although Lawrence claimed to have felt like “a man dropping a heavy load,” there seems to have been no doubt in his mind, or Allenby’s, that he was returning to Britain to take up the Arab cause.

Lawrence was exhausted, thin almost to emaciation, weighing no more than eighty pounds, as opposed to his usual 112. This is borne out both by Lawrence’s older brother Bob, who was shocked by his appearance when he arrived home, and by James McBey’s startling portrait of him, painted in Damascus, in which his face is as thin and sharp as a dagger, and his eyes are enormous and profoundly sad. It is the face of a man worn out by danger, stress, responsibility, and disappointment. The faintly ironic smile on his lips seems to suggest that he already suspects nothing he fought for is likely to happen. The confusion, chaos, jealousies, and violence in Damascus may already have convinced him that there was not going to be a noble ending to his adventures.

On the ship from Port Said to Taranto, Italy, Lawrence persuaded his fellow passenger and former fellow soldier, Lord Winterton, a member of Parliament, to write on his behalf requesting interviews with Lord Robert Cecil (the undersecretary of state for foreign affairs*) and A. J. Balfour (the foreign secretary). Lawrence also interrupted his journey in Rome for a talk with Georges-Picot about the French position in Syria. During the course of this discussion Picot made it very clear, if there had been any doubt in Lawrence’s mind, that France remained determined to have Lebanon and Syria, and rule them from Paris in much the same way as Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. There was a place for Prince Feisal as the head of a government approved by France, and under the tutelage of a French governor-general and a French military commander, but he should have no illusions about creating an independent sovereign state.

Tragedy: Lawrence, exhausted, emaciated, and shorn of illusions. Damascus, 1918.

There occurred on this journey an incident that puzzled Lawrence’s biographers while he was still alive and provided material for them long after his death. Either at Taranto, between the ship and the train, or at Marseille, where the train presumably stopped before going on to Paris, Lawrence saw a British major dressing down a private for failing to salute, and humiliating the private by making him salute over and over again. Lawrence intervened, and when the major asked him what business it was of his, he removed his uniform mackintosh, which had no epaulets and hence no badges of rank; revealed the crown and two stars of a full colonel on his shoulders; pointed out that the major had failed to salute him; and made the major do so several times. Lowell Thomas’s version of this incident differs radically from Liddell Hart’s: according to Thomas, Lawrence asks the railway transport officer (RTO) at the Marseille station, a lieutenant-colonel (“a huge fellow, with a fierce moustache”), what time his train leaves, is snubbed, and then takes off his raincoat to show that he outranks the pompous RTO. In Robert Graves’s biography, Lawrence sees “a major … bullying two privates … for not saluting him,” and neglects to return their salute until Lawrence appears and makes him do so. Whichever one of these stories is true, they all illustrate the same point, which is Lawrence’s dislike of conventional discipline and of officers’ abusing their power over “other ranks.”

One point that the indefatigable Jeremy Wilson has clearly demonstrated in his exhaustive authorized biography is that there is always a germ of truth in every story Lawrence told about himself, though over the years Lawrence sometimes improved and embellished such stories. Taranto seems much more likely as the place where this occurred, first of all because there were more British troops at Taranto, but also because it had been only a matter of days then since General Chauvel’s inopportune complaint in Damascus about the Arabs’ failing to salute British officers, so the subject of saluting may still have been very much on Lawrence’s mind. This was also the first time in more than two years that Lawrence was dressed in a British uniform and found himself among British officers and men. In the desert, he had neither saluted nor encouraged British personnel below his rank to salute him. Now he was back in the army. He was returning to a world where rank mattered and class distinctions were absolute, a world very different from the rough simplicity of desert warfare.

He arrived home “on or about October 24th,” but spent only a few days with his family in Oxford before getting down to the business of securing Syria for Feisal and the Arabs. Only four days later, thanks to Winterton’s letter of introduction, he had a long interview with Lord Robert Cecil, perhaps the most eminent, respectable, and idealistic figure in Lloyd George’s government. Cecil was a son of the marquess of Salisbury, the Conservative prime minister who had dominated late Victorian politics; the Cecil family traced its tradition of public service back to 1571, when Queen Elizabeth I made William Cecil her lord treasurer. Robert Cecil was an Old Etonian, an Oxonian, a distinguished and successful lawyer, an architect of the League of Nations, and a firm believer in Esperanto as a universal common language. He would go on to win the Nobel Peace Prize, among many other honors. The fact that he was willing to see Lawrence on such short notice is a tribute not only to Lord Winterton’s reputation, but to Lawrence’s growing fame as a hero. Of course he was not yet the celebrity he would become when Lowell Thomas had established him in the public mind as “Lawrence of Arabia,” but his service in the desert was already sufficiently well known to open doors that would surely have remained closed to anyone else. Cecil’s notes on the meeting—in which he shrewdly comments that Lawrence always refers to Feisal and the Arabs as “we"—make it clear that Lawrence’s ideas on the future of the Middle East were both intelligent and far-reaching, and were viewed with sympathy by one of the most influential figures in what would later come to be called “the establishment.” The next day, Lawrence had an equally long and persuasive discussion with Lieutenant-General Sir George Macdonogh, GBE, KCB, KCMG, adjutant-general of the British army, and creator of MI7, an intelligence unit intended to sabotage German morale. Macdonogh, who was very well informed about the Middle East, afterward circulated to the war cabinet a long and admiring report on his discussion with Lawrence, the gist of which was that the Sykes-Picot agreement should be dropped, Syria should be “under the control” of Feisal, Feisal’s half brother Zeid should rule northern Mesopotamia, and Feisal’s brother Abdulla should rule southern Mesopotamia—in short, Lawrence converted Macdonogh.

Perhaps as a result of the “Macdonogh memorandum,” Lawrence was invited to address the Eastern Committee of the war cabinet on October 29, only five days after he had arrived back in Britain. Deducting two days for the time he had spent with his family in Oxford, Lawrence had reached the highest level of the British government in seventy-two hours. Judging from Macdonogh’s memorandum, he did so first by the lucidity and intelligence of his ideas, and second because what he had to say was viewed with intense sympathy. The British government believed, like Lawrence, that the Sykes-Picot agreement should be discarded; that Arabs and Zionists should cooperate in Palestine under the protection of a British administration; that Mesopotamia should be an Arab “protectorate,” ruled from Cairo, not from Delhi; and that Arab ambitions (and British promises) in Syria should be respected. If Lawrence was not quite preaching to the converted, he was at any rate preaching to those who were prepared to convert. On the other hand, since there were still few signs that the war was about to end suddenly—in twenty-three days, in fact—the general feeling was that there was still plenty of time to bring the French around to this point of view. The British also believed that Woodrow Wilson would certainly denounce the Sykes-Picot agreement as a perfect example of secret diplomacy, which he wanted to end once and for all. Lawrence, who had after all stopped in Rome to talk directly to Picot, had a good idea of just how intransigent the French were likely to be; but perhaps sensibly, he does not seem to have raised this with either Cecil or Macdonogh.

In any event, Lawrence’s appearance at the Eastern Committee of the war cabinet is almost as much of a puzzle for biographers as the story about the saluting incident at Taranto or Marseille. He himself once said that he “was more a legion than a man,” a reference to the man from Gadara whose name was “Legion” because he was possessed by so many demons. Lawrence found no difficulty in presenting different versions of himself to people throughout his lifetime, hence the often wildly conflicting reactions to him.

The meeting was chaired by the Rt. Hon. the Earl Curzon, KG, GSCI, GCIE, PC, former viceroy of India, leader of the House of Lords, one of the most widely traveled men ever to sit in a British cabinet, and perhaps one of the most formidable and hardworking political figures of his time. A graduate of Eton and Balliol College, Oxford, he was in some respects everything that Lawrence was not: his career at Oxford had been glittering, both academically and socially; he was renowned for his arrogance and inflexibility (caused in part by the fact that a riding injury in his youth obliged him to wear a steel corset that inflicted on him unceasing, lifelong pain, and made his posture seem unnaturally stiff and straight). His attitude toward life was grandly aristocratic, so that he sometimes seemed more appropriate to the eighteenth than to the twentieth century.

As Lawrence later told the story, he sat before the committee while Curzon made a long speech, outlining and praising Lawrence’s feats—a speech that for some reason Lawrence “chafed at.” Lawrence may, as he later complained, have found this speech patronizing, particularly since he knew most of the members of the committee, but it is more likely that Curzon’s grandiloquent manner simply rubbed him the wrong way. In any case, once Curzon finished, he asked if Lawrence wished to say anything, and Lawrence answered: “Yes, let’s get to business. You people don’t understand yet the hole you have put us all into.”

Lawrence, writing to Robert Graves in 1927, added: “Curzon burst promptly into tears, great drops running down his cheeks, to an accompaniment of slow sobs. It was horribly like a mediaeval miracle, a lachryma Christi, happening to a Buddha. Lord Robert Cecil, hardened to such scenes, presumably, interposed roughly, ‘Now old man, none of that.’ Curzon dried up instanter.” Lawrence then warned Graves, “I doubt if I’d publish it, if you do, don’t put it on my authority. Say a late member of the F.O. [Foreign Office] Staff told you.”

There are many questions about this account, some of which are obvious. First, why would Curzon ask if there was anything Lawrence wished to say, since Lawrence’s whole reason for being there was to speak to the committee? Second, it is hard to imagine Lord Robert Cecil, the most gentlemanly of men, speaking to anyone “roughly.” The spectacle of Curzon sobbing at a meeting of a committee of the war cabinet would certainly have startled the other members, and in fact, after Graves’s biography of Lawrence was published, Cecil wrote to Curzon’s daughter, Lady Cynthia Mosley,* denying that the incident had ever happened: “I feel quite certain that your father never burst into tears, and I am even more certain that I have never addressed him in the way described under any circumstances.” As for Curzon’s speech about Lawrence, Cecil wrote: “Colonel Lawrence listened with the most marked attention, and spoke to me afterwards in the highest appreciation of your father’s attitude.”

Of course Cecil may have felt it was his obligation to be polite to Lady Cynthia about her father, but nobody else who was present at the meeting seems to have commented on the incident, and this fact raises a certain amount of doubt about Lawrence’s story. Indeed, given how influential Curzon was, and the importance of Lawrence’s meeting with the committee, why on earth would Lawrence have gone out of his way to attack him?

Against this must be set the rumor that Curzon burst into tears in 1923 when Lord Stamfordham, the king’s private secretary, informed him that George V had decided to choose Stanley Baldwin instead of Curzon as prime minister, after Bonar Law announced his retirement. If Curzon could burst into tears on that occasion, then he could presumably have burst into tears in front of Lawrence and the members of the Eastern Committee of the war cabinet; but even so there is a certain gloating quality in Lawrence’s letter to Graves, which makes one uncomfortable. In addition, Lawrence’s suggestion that Graves should attribute the story to “a late member of the F.O. Staff” when he himself is the source of it seems rather devious for a man who set such high standards for himself.

In Scottish courts there used to be a verdict falling between “guilty” and “not guilty,” namely “not proven.” Lawrence’s story about Curzon bursting into tears seems to fit into that category perfectly.

The day after Lawrence’s appearance before the Eastern Committee of the war cabinet, he was involved in an even more controversial meeting at a much higher level. Allenby’s letter to Clive Wigram had produced a private audience with the king, who was in any case, given his interest in military affairs, curious to meet young Colonel Lawrence. Allenby had also recommended Lawrence for the immediate award of a knighthood, a Knight Companion of the Order of the Bath (KCB), which was one step up in the senior of the two orders that Lawrence had already been awarded. Lawrence had already made it clear to the king’s military secretary that he did not wish to accept this honor, and that he merely wished to inform the king about the importance of Britain’s living up to the promises made to King Hussein, but whether this information was passed on accurately is uncertain. It seems unlikely that two men as realistic as General Allenby and Lord Stamfordham would have hidden from the king Lawrence’s unwillingness to receive any form of decoration—perhaps the most important part of Stamfordham’s job as a courtier was to ensure that the king was spared any kind of surprise or embarrassment, and Allenby was an ambitious man who would not have wished to offend his sovereign.

Once Lawrence arrived at Buckingham Palace, he learned that the king intended to hold a private investiture, and present him with the insignia of his CB and his DSO. It seems very likely that this was the king’s own idea, that he intended it as a thoughtful gesture toward a hero. Once he made up his mind to do it, neither Stamfordham nor the military secretary attempted to confront him over the matter—George V’s stubbornness and sharp temper were well known, and when he had made up his mind to do something he was not easy to divert. Thus Lawrence was ushered in to see the king and left to explain himself that he would not accept any decorations or honors, either old or new.

We have Lawrence’s account of what he said to the king, in a letter he sent to Robert Graves with corrections he wanted Graves to make in his biography: “He explained personally to his Sovereign that the part he had played in the Arab Revolt was, to his judgment, dishonourable to himself and to his country and government. He had by order fed the Arabs with false hopes and would be obliged if he were relieved of the obligation to accept honors for succeeding in his fraud. Lawrence now said respectfully as a subject, but firmly as an individual, that he intended to fight by straight means or crooked until the King’s ministers had conceded to the Arabs a fair settlement of their claims.”

“In spite of what has been published to the contrary,” Lawrence added to Graves, “there was no breach of good relations between subject and sovereign.” In later years, the king, who liked to improve a good story as much as Lawrence, would tell how Lawrence unpinned each decoration as soon as the king had pinned it on him, so that in the end the king was left foolishly holding a cardboard box filled with the decorations and their red leather presentation cases. In fact the king seems to have been more curious than offended. Lawrence explained, with his usual charm, that it was difficult to serve two masters—Emir Feisal and King George—and that “if a man has to serve two masters it was better to offend the more powerful.”

At first the king was under the impression that Lawrence was turning down the KCB because he expected something better, and offered him instead the Order of Merit, a much more distinguished honor—it has been described as “the most prestigious honor on earth"—in the personal gift of the sovereign, founded by King George V’s father and limited to a total of twenty-four members. (Past members have included Florence Nightingale, and subsequent ones Graham Greene, Nelson Mandela, and Lady Thatcher.) This was not an offer to be taken lightly, but Lawrence refused it, at which point the king sighed in resignation, and said, “Well, there’s one vacant; I suppose it will have to go to Foch.”

The interview was cozy rather than formal. It had begun with the king “warming his coat tails in front of the fire at Buckingham Palace, the Morning Postin his hands, and complaining: ‘This is a bad time for kings. Five new republics today.’ “ Lawrence may have consoled the king by saying that he had just made two kings, but this seems unlikely—Hussein had made himself a king without Lawrence’s help, and Feisal had not yet been made one.* Lawrence had brought with him as a present for the king the gold-inlayed Lee-Enfield rifle that Enver Pasha had presented to Feisal, and that Feisal later gave to Lawrence in the desert. The king, an enthusiastic and expert shot and gun fancier himself—apart from stamp collecting, guns were his favorite pastime—was delighted with the rifle, which remained in the royal collection of firearms for many years until it was presented to the Imperial War Museum, where it is now a prized exhibit.

Later, Lord Stamfordham, in a letter to Robert Graves from Balmoral Castle, the royal family’s summer residence in Scotland, confirmed most of Lawrence’s account of the interview, and since Stamfordham and Lawrence dined together amicably at one point afterward, it does not seem likely that George V was offended—Stamfordham would hardly have dined “amicably” with somebody who had offended his sovereign. The two people at court who wereoffended were the queen and the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VIII and then the duke of Windsor), both of whom resented what they interpreted as discourtesy to the king, a resentment that Edward expressed strongly all his life.

During the course of the conversation, Lawrence expressed the opinion that all the members of his majesty’s government were “crooks,” not an uncommon opinion so long as Lloyd George was prime minister. The king was “rather taken aback” but by no means shocked or offended—his own opinion of Lloyd George was no better than Lawrence’s. “Surely you wouldn’t call Lord Robert Cecil a crook?” he asked, however, and Lawrence had to agree with the king that Cecil was certainly an exception.

In his letter to Graves, Stamfordham also made an interesting point: Lawrence had explained to the king “in a few words” that “he had made certain promises to King Feisal, that these promises had not been fulfilled and, consequently, it was quite possible that he might find himself fighting against the British Forces, in which case it would be obviously impossible and wrong to be wearing British decorations.”

One might have thought that if anything was going to shock the king it would be Lawrence’s suggestion that a British officer wearing the king’s uniform might have to take up arms against his own country, with or without his decorations, but the king seems either to have taken that in his stride, or to have decided that it was merely self-dramatizing nonsense, as indeed it was.

All things considered, Lawrence’s talk with the king was not nearly as controversial as it has often been described, but it was nevertheless surely a tactical mistake on Lawrence’s part. First of all, while Lawrence was within his right to decline new honors, he could not “turn down” those he already had, something the king understood better than Lawrence. For that matter Lawrence could just as easily have accepted the decorations without a fuss, then neglected to wear them afterward, and it would have made no difference at all. More important, the story made its way around London quickly, and usually it took the form of Lawrence being rude to the king, though he had not in fact been rude. This perplexed or outraged many people who might otherwise have admired Lawrence, or been helpful to him in getting the Arabs what they wanted.

Churchill was among them, until Lawrence had an opportunity to explain to him in private what had really happened. In those days, at least, nobody ever benefited in the long run from having been thought rude to the royal family—as Churchill knew well, since his beloved father, Lord Randolph Churchill, had learned that lesson after offending King Edward VII.

Lawrence spent the next few days preparing a long paper on the Middle East for the war cabinet’s committee, in which he succeeded in presenting both his own views and those of Feisal as if they were the same. In fact, Lawrence was prepared to accept a far higher degree of British involvement, direct and indirect, in Arabian affairs than either Feisal or his father would have wished; it was France (and direct French rule) Lawrence wanted to keep out of the Middle East, not Britain. He clung firmly to the heart of the matter—an independent Arab state in Syria, with Feisal as its ruler, under some kind of British supervision; a British-controlled Arab state in what is now Iraq; and “Jewish infiltration” in Palestine, “if it is behind a British as opposed to an international faзade.” He was effectively recommending repudiation of the Sykes-Picot agreement, and firing two warning signals: one of them idealistic, “the cry of self determination” that the United States would be likely to approve; the other practical, the information that Feisal would be willing to accept increased Zionist immigration in Palestine onlyif it remained under British control, but not if Palestine was placed under international control as the Sykes-Picot agreement provided.

Lawrence delivered this document to the Eastern Committee on November 4, and went on to meet with Winston Churchill, then minister of munitions, who had presumably not yet heard about Lawrence’s meeting with the king. This was to be the beginning of one of the most significant of Lawrence’s postwar friendships with older and more powerful men. Churchill not only was impressed by the young colonel, but would go on to become Lawrence’s lifelong supporter. Perhaps nobody would describe better the effect Lawrence had on his contemporaries than Churchill at the forthcoming peace conference: “He wore his Arab robes, and the full magnificence of his countenance revealed itself. The gravity of his demeanor; the precision of his opinions; the range and quality of his conversations; all seemed enhanced to a remarkable degree by the splendid Arab head-dress and garb. From amid the flowing draperies his noble features, his perfectly chiseled lips and flashing eyes loaded with fire and comprehension shone forth. He looked like what he was, one of Nature’s greatest princes.”