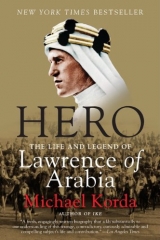

Текст книги "Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia "

Автор книги: Michael Korda

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 55 страниц)

MICHAEL KORDA

HERO

The Life and Legend ofLawrence of Arabia

For Margaret, again and always

And not by eastern windows only,

When daylight comes, comes in the light,

In front the sun climbs slow, how slowly,

But westward, look, the land is bright.

—Arthur Hugh Clough,

“Say Not the Struggle Naught Availeth”

I do not pretend to have understood T. E. Lawrence fully, still less to be able to portray him; there is no brush fine enough to catch the subtleties of his mind, no aerial viewpoint high enough to bring into one picture the manifold of his character…. I am not a tractable person or much of a hero-worshipper, but I could have followed Lawrence over the edge of the world. I loved him for himself, and also because there seemed to be reborn in him all the lost friends of my youth…. If genius be, in Emerson’s phrase, “a stellar and undiminishable something,” whose origin is a mystery and whose essence cannot be defined, then he was the only man of genius I have ever known.—John Buchan (Lord Tweedsmuir),

Pilgrim’s Way

The will is free;

Strong is the soul, and wise and beautiful;

The seeds of godlike power are in us still;

Gods are we, bards, saints, heroes, if we will!

—Matthew Arnold,

written in a copy of Emerson’s Essays

He was indeed a dweller upon mountain tops where the air is cold, crisp and rarefied, and where the view on clear days commands all the Kingdoms of the world and the glory of them.

—Winston S. Churchill,

on Lawrence

Oh! If only he had died in battle! I have lost my son, but I do not grieve for him as I do for Lawrence…. I am counted brave, the bravest of my tribe; my heart was iron, but his was steel. A man whose hand was never closed, but open…. Tell them…. Tell them in England what I say. Of manhood, the man, in freedom, free; a mind without equal; I can see no flaw in him.

—Sheikh Hamoudi,

on being told of Lawrence’s death

Preface

It has been ninety-two years since the end of World War I, known until September 1939 as the Great War. Of the millions who fought in it, of the millions who died in it, of its many heroes, perhaps the only one whose name is still remembered in the English-speaking world is T. E. Lawrence, “Lawrence of Arabia.”

There are many reasons for this—even during his own lifetime Lawrence was transformed into a legend and a myth, the realities of his accomplishments overshadowed by the bright glare of his fame and celebrity—and it is the purpose of this book to explore them, as objectively, and sympathetically, as possible, for Lawrence was from the beginning a controversial figure, and one who very often did his best to cover his tracks and mislead his biographers.

Since the British government began to open its files and release what had hitherto been secret documents in the 1960s, Lawrence’s feats have been confirmed in meticulous detail. What he wrote that he did, he did—if anything he underplayed his role in the Arab Revolt, the 1919 Paris Peace Conference that followed the Allies’ victory, and the British effort to create a new Middle East out of the shards of the defeated Ottoman Empire in 1921 and 1922. Many of the problems that confront us in the Middle East today were foreseen by Lawrence, and he had a direct hand in some of them. Today, when the Middle East is the main focus of our attention, and when insurgency, his specialty, is the main weapon of our adversaries, the story of Lawrence’s life is more important than ever.

As we shall see, he was a man of many gifts: a scholar, an archaeologist, a writer of genius, a gifted translator, a mapmaker of considerable talent. But beyond all that he was a creator of nations, of which two have survived; a diplomat; a soldier of startling originality and brilliance; an authentic genius at guerrilla warfare; an instinctive leader of men; and above all, a hero.

We have become used to thinking of heroism as something that simply happens to people; indeed the word has been in a sense cheapened by the modern habit of calling everybody exposed to any kind of danger, whether voluntarily or not, a “hero.” Soldiers—indeed all those in uniform—are now commonly referred to as “our heroes,” as if heroism were a universal quality shared by everyone who bears arms, or as if it were an accident, not a vocation. Even those who die in terrorist attacks, and have thus had the bad luck to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, are described as “heroes,” though given a choice most of them would no doubt have preferred to be somewhere else when the blow was struck.

Lawrence, however, was a hero in the much older, classical sense—it is surely no accident that he decided to translate Homer’s Odyssey—and like the heroes of old he trained himself, from early childhood, for the role. Without the war, Lawrence might never have accomplished his ambition, but once it came he was prepared for it, both morally and physically. He had steeled himself to an almost inhuman capacity to endure pain; he had studied the arts of war and of leadership; he had carefully honed his courage and his skill at leading men—like the young Napoleon Bonaparte he was ready to assume the role of hero when fate presented him with the opportunity. He seized it eagerly with both hands in 1917, and like Ajax, Achilles, Ulysses, he could never let go of it. No matter how hard he tried to escape from his own legend and fame later on, they stuck to himto the very end of his life, and beyond: seventy-five years after his death he remains as famous as ever.

This book, therefore, is about the creation of a legend, a mythic figure, and about a man who became a hero not by accident, or even by one single act of heroism, but who made himself a hero by design, and did it so successfully that he became the victim of his own fame.

“His name will live in history,” King George V wrote on Lawrence’s death in 1935.

And it has.

CHAPTER ONE

“Who Is This Extraordinary Pip-Squeak?”

In the third summer of the world’s greatest war a small garrison of Turkish soldiers still held the port of Aqaba, on the Red Sea, as they had from the beginning—indeed since long before the beginning of this war, for Aqaba, the site of Elath during biblical times, and later garrisoned during the Roman era by the Tenth Legion, had been part of the Ottoman Empire for centuries, steadily declining under Turkish rule into a small, stiflingly hot place hardly bigger than a fishing village, reduced by 1917 to a few crumbling houses made of whitewashed dried mud brick and a dilapidated old fort facing the sea. Its site was on the flat, narrow eastern shore amid groves of date palms, in the shadow of a jagged wall of mountains as sharp as a shark’s teeth and a steep plateau that separated it from the great desert stretching to Baghdad in the east, north to Damascus and south to Aden, more than 1,200 miles away.

Today a busy, thriving resort city and the principal port of Jordan, a nation which did not then exist, Aqaba is famous for its beaches and its coral reefs, which attract scuba divers from all over the world. It is situated at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba, which is separated from the Gulf of Suez by the spade-shaped southern tip of the Sinai. At the narrow mouthof the Gulf of Aqaba, some archaeologists believe, lies a shallow “land bridge” over which Moses led the Jews across the Red Sea on their flight from Egypt. From the first days of the war, Aqaba had attracted the attention of British strategists in the Middle East, starting with no less imposing a figure than that remote and awe-inspiring military and diplomatic potentate, the victor of Omdurman, sirdar, or commander in chief, of the Egyptian army and British agent and consul general in Egypt,* Field Marshal the Earl Kitchener, KG, KP, OM, GSCI, GCMG, GCIE.

It was not that Aqaba itself was such a valuable prize, but a rough dirt road, or track, ran northeast from it to the town of Maan, some sixty miles away as the crow flies, and a major stop on the railway line the Turks had built with German help before the war from Damascus to Medina. From Maan it seemed possible—at any rate to those looking at a map in Cairo or London rather than riding a camel over a waterless, rocky desert landscape—to threaten Beersheba and Gaza from the east, thus at one stroke cutting off the Turks’ connection with their Arabian empire, eliminating once and for all the Turkish threat to the Suez Canal and making possible the conquest of Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Seen on the map, the Gulf of Aqaba was like a knife blade aimed directly at Maan, Amman, and Damascus. With Aqaba as a supply base, it might be feasible to attack the richest and most important part of the Ottoman Empire, whose inhabitants, divided though they might be by tribe, religion, tradition, and prejudice, could perhaps be encouraged, if only out of self-interest, to rise against the Turks.

Three years of war did not shift the Turks; nor did anything seem likely to. The Turkish garrison in Aqaba was so weak, dispirited and isolated that small British naval landing parties had managed to get onshore and take a few prisoners, but the prisoners only confirmed what anybody on a naval vessel could tell from the sea with a pair of binoculars—a single narrow, winding passage, what we might call a canyon and the Arabs a wadi, cut through the steep mountains to the north of the town, and the Turks had spent the last three years fortifying the rugged, rocky high ground on either side of it with trenches that overlooked the beaches. The high ground rose sharply, in the form of natural rocky terraces, like giant steps, providing defensive positions for machine gunners and riflemen. It would be easy enough for the Royal Navy to land troops on the beaches at Aqaba, assuming troops could be made available for that purpose, but once ashore they would have to fight their way uphill against a stubborn and well-entrenched enemy, in a landscape whose chief feature, apart from blistering, overwhelming heat, was a lack of drinking water, except for the few wells forming the strongpoints of the Turkish defense system.

Many British officers underrated, even despised the Turkish army—the general opinion was that Turkish soldiers were poorly trained and poorly armed, as well as slovenly, cruel, and reluctant to attack, while their officers were effete, poorly educated, and corrupt. This opinion persisted despite the fact that when a combined British, Australian, and New Zealander army landed at Gallipoli in April 1915, in an attempt to take Constantinople and open up a year-round warm-water route through the Dardanelles to Allied shipping (without which the beleaguered Russian Empire seemed certain to collapse), it was fought to a standstill by an inferior number of Turks. The British were obliged to evacuate after eight months of fighting, leaving behind 42,957 dead—in addition to 97,290 men seriously wounded and 145,000 gravely ill, mostly from dysentery. The failure at Gallipoli briefly ended the hitherto charmed political career of Winston Churchill, the first lord of the admiralty, who had been a prime mover of the campaign. The defeat also ensured the collapse of the Russians’ army and their monarchy, and ought to have taught the British that in a defensive role Turkish soldiers were as stubborn and determined as any in the world. Further proof was not lacking. Twice, the unfortunate General Sir Archibald Murray, GCB, GCMG, CVO, DSO, who commanded the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, tried to break through the Turkish lines in front of Gaza, and twice British troops were driven back with heavy losses by the unyielding, entrenched Turkish infantry.

As for the corruption of the Turkish officer class and politicians, whileit was notoriously widespread, here, too, there were exceptions. When a British army advancing from the port city of Basra, in what was then Mesopotamia and is now Iraq, in an attempt to capture Baghdad, was trapped and surrounded less than 100 miles from its goal in the town of Kut al-Amara in December 1915, the British government tried to bribe the Turkish commander to lift the siege. A twenty-eight-year-old temporary second-lieutenant and acting staff captain named T. E. Lawrence, on the intelligence staff of General Murray’s predecessor in Cairo, was sent by ship from Suez to Basra with instructions from Kitchener himself, then secretary of state of war, to offer the Turkish commander, Khalil Pasha, up to Ј1 million (about $90 million in contemporary terms) to allow the British forces in Kut to retreat back to Basra.

On the morning of April 29, 1916, Lawrence and two companions—one of them Aubrey Herbert, a member of Parliament and an expert on Turkey—walked out of the British lines with a white flag and, after being blindfolded, were led to Khalil’s quarters, where, following lengthy negotiations in French, he firmly but politely turned the offer down, even when it was doubled at the last minute. Since it was by then too late for the three British officers to go back to their own lines, Khalil offered them his hospitality for the night, and gave them, according to Lawrence, “a most excellent dinner in Turkish style.” Of the 13,000 British and Indian soldiers who had survived the 147-day siege and were still alive to surrender at Kut, more than half would die in Turkish prisoner-of-war camps—from disease; starvation; malnutrition; the effects of a harsh climate; and Turkish incompetence, indifference, and cruelty with regard to prisoners of war.

In the autumn of 1916, less than six months after the dinner with Khalil Pasha behind the Turkish lines at Kut, Aqaba was very much on Lawrence’s mind. He was perhaps the only officer in Cairo who had actually been in Aqaba before the war, swum in its harbor, and explored the countryside behind it. He had not been at all surprised when he was picked out, as a mere acting staff captain, to offer a Turkish general a Ј1 millionbribe—among his character traits was supreme self-confidence—since his knowledge of the Turkish army was appreciated at the highest level, both in Cairo and in London. Unmilitary in appearance he might be—he often neglected to put on his Sam Browne belt, and he wore leather buttons, rather than shiny brass ones, on his tunic—but few people disputed his intelligence, his attention to detail, or his capacity for hard work. His manner was more that of an Oxford undergraduate than a staff officer, and many people below the rank of field marshal or full general were offended by it, or dismissed him as an eccentric poseur and show-off who did not belong in the army at all—not only did Lawrence not “fit in,” but he was a nonsmoker, a teetotaler, and, when he bothered to eat at all, by inclination a vegetarian, except on occasions when he was obliged to please his Arab hosts by sharing their mutton. Neither his sense of humor nor his unmistakable air of intellectual superiority appealed to more conventional spirits, and his short stature (he was five feet five inches tall), a head that seemed disproportionately large for his body, and unruly blond hair set him apart from fellow junior officers. One of his companions on the trip behind Turkish lines described him as “an odd gnome, half cad—with a touch of genius,” and a superior at headquarters in Cairo may have summed up the general opinion there of Lawrence when he asked, “Who is this extraordinary pip-squeak?”

To those who judged him by his quirky manner and his ill-fitting, wrinkled, off-the-rack uniform, the cuffs of his trousers always two or three inches above his boots, the badge sometimes missing from his peaked cap, Lawrence did not cut a soldierly figure, so most of them failed to notice the intense, ice-blue eyes and the unusually long, firm, determined jaw, a facial structure more Celtic than English. It was the face of a nonreligious ascetic, capable of enduring hardship and pain beyond what most men would even want to contemplate, a true believer in other people’s causes, a curious combination of scholar and man of action, and, most important of all, a dreamer.

Lawrence was also somebody who, however improbable it might seem to those around him in Cairo, aspired to be both a leader of men and ahero. He claimed that when he was a boy his ambition had been “to be a general and knighted by the time he was thirty,” and both goals would come close to being within his grasp at that age, had he still wanted them. Lawrence’s duties in Cairo seemed tailor-made for his talents. After an initial period of mapmaking, at which he was something of a self-taught expert, he soon turned himself into a kind of liaison between military intelligence (which came under the War Office) and the newly formed Arab Bureau (which came under the Foreign Office), a situation that gave him a certain independence. He became, largely through interviewing Turkish prisoners of war, the leading expert on the battle order of the Turkish army—which divisions were where, who commanded them, and how reliable their troops were—and sometimes edited the Arab Bulletin, a kind of secret magazine or digest that gathered every kind of intelligence about the Arab world and the Turkish army for the benefit of senior officers. Lawrence wrote a lot of the Arab Bulletin himself (published between 1916 and 1919, it would eventually run to over 100 issues and many hundreds of pages); and not only was it lively and well written (unlike most intelligence documents), combining the virtues of a gossip column and an encyclopedia, but it also reflected his own point of view, and had a considerable influence on British policy, both in Cairo and in London. Since Lawrence’s mentor from his undergraduate days at Oxford, the archaeologist and Oxford don D. G. Hogarth (repackaged, for wartime purposes, as a commander in the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve) was a major figure in the Arab Bureau, Lawrence was naturally drawn more toward the bureau than toward military intelligence; but in both departments he found a certain number of kindred souls who were able to appreciate his keen mind despite his eccentricities and unmilitary behavior.

One of these was Ronald Storrs, Oriental secretary of the British Agency in Cairo, a civil servant and Foreign Office official whose job it was to advise the British high commissioner, Sir Henry McMahon—the de facto ruler of Egypt, the position Kitchener had held until he joined the war cabinet in 1914—on the subtleties of Arab politics. It is remarkable but very typical of Lawrence that he and Storrs, though very different creatures, became friends on first meeting, and remained friends to the end of Lawrence’s life—Storrs would be one of his pallbearers. Storrs was sociable, ambitious, fond of the good things of life, an eminently “clubbable man,” to borrow a phrase from Dr. Johnson, and would go on after the war to become military governor of Jerusalem—a post once held by Pontius Pilate, as Storrs himself pointed out with good humor—and to a happy and contented marriage. Storrs regarded Lawrence with something like affectionate awe—"Into friendship with T. E. Lawrence I know not how I entered,” he would write in his memoir, Orientations; “then suddenly it seemed I must have known him for many years.” For his part, Lawrence would later describe Storrs in Seven Pillars of Wisdom with backhanded affection: “The first of us was Ronald Storrs … the most brilliant Englishman in the Near East, and the deepest, though his eyelids were heavy with laziness, and his eyes dulled by care of self, and his mouth made unbeautiful by hampering desires.” Storrs’s ambitions were realistic, and he pursued them sensibly and zealously—indeed, Orientations sometimes reminds the reader of Samuel Pepys’s diaries in its frank admission of a civil servant’s determination to climb the ladder of success—and they would eventually be achieved by marriage and a knighthood. By contrast, Lawrence sensibly concealed from Storrs his own more schoolboyish daydreams of being a knight and a general before the age of thirty, let alone of being a hero, in the full classical sense of the word, as well as a founder of nations. Nobody, least of all Storrs, could ever accuse Lawrence of “laziness,” “care of self,” or “hampering desires.” He loved to spend time in Storrs’s apartment in Cairo, borrowing books in Greek or Latin, which he was always careful to return, listening to Storrs play the piano, and talking about music and literature; but even so, Storrs seems to have detected early on that Lawrence was more than an Oxonian archaeologist in an ill-fitting uniform—that behind the facade was a man of action.

When, in mid-October 1916, Lawrence accompanied Storrs on a journey to Jidda in the Hejaz, the Red Sea port closest to Mecca, to negotiate with the infinitely difficult and obstinate Sharif Hussein ibn Ali-el-Aun about British support for the Arab Revolt, Storrs’s postprandial naps and his reading of Henry James’s The Ambassadors and H. G. Wells’s Mr. Britling in the stifling privacy of his cabin on board a British steamer were interrupted by Lawrence’s “revolver practice on deck at bottles after lunch,” which “tore my ears and effectually ruined my siesta.” Had Storrs but known it, weapons had always played a significant part in Lawrence’s life—he was taught by his father to be an excellent shot, and on his journeys through the Middle East before the war as an undergraduate and an apprentice archaeologist he had always gone armed; on one occasion, he had fired back at an Arab peasant who fired at him, either wounding his assailant or startling the Arab’s horse; and on another he was beaten badly on the head with his own automatic pistol by a robber who, fortunately for Lawrence, was unable to fathom how to release its safety catch.

In later years Lawrence liked to say that he made himself so difficult in the role of a superior young know-it-all that military intelligence was only too happy to let him go to the Arab Bureau, which had more the atmosphere of a Senior Common Room at Oxford than of the army. He boasted of making himself “quite intolerable to the Staff…. I took every opportunity to rub into them their comparative ignorance and inefficiency (not difficult!) and irritated them further by literary airs, correcting split infinitives and tautologies in their reports.” Perhaps as a result, nobody objected when Lawrence took a few days’ leave in Storrs’s company, and Storrs was happy enough to have him as a travel companion.

Lawrence may have been the only person in Cairo who would have thought of a journey to Jidda as a lark. A stifling, dusty rail journey from Cairo to Suez was followed by a sea journey of almost 650 miles on board a slow steamer taken over by the Royal Navy, the heat made bearable only by the breeze of the ship’s movement. “But when at last we anchored in the outer harbor,” Lawrence wrote of his first sight of Jidda, “off the white town hung between the blazing sky and its reflection in the mirage that swept and rolled over the wide lagoon, then the heat of Arabia came out like a drawn sword and smote us speechless.”

For Storrs, the journey to Jidda—it was his third—however tedious and hot, was part of his job; the notion of an Arab revolt against the Turks had been an idйe fixe with British strategists in the Middle East since long before the war. Indeed Kitchener and Storrs had discussed the possibility with Emir (Prince) Abdulla—one of the sons of Hussein, sharif and emir of Mecca—before it was even certain that Turkey would join the Germans and the Austro-Hungarians against the British, the French, and the Russians. In October 1914, three months after war had broken out, and only a few days after Turkey had finally (and fatally) joined the Central Powers, Kitchener sent a grandiloquent message to Sharif Hussein from London, with an open proposal to back an Arab revolt: “Till now we have defended and befriended Islam in the person of the Turks: henceforth it shall be in that of the noble Arab. It may be that an Arab of true race will assume the Caliphate at Mecca or Medina, and so good may come by the help of God out of all the evil which is now occurring.”

This pious hope, fortified by Kitchener’s tactfully phrased suggestion that with British help and support the sharif might replace the sultan of Turkey as caliph, the spiritual leader of Islam, eventually led both to a revolt, so far mostly sporadic and unsuccessful, and to spirited bargaining, in which Storrs was one of the chief players—hence, his sea voyage to a place where Christians, even when bearing gifts, or the promise thereof, were still regarded as infidels. The Hejaz, the mountainous coastal region of Arabia bordering the Red Sea, contained two of the three holiest cities of Islam: Mecca and Medina. (The third, soon to be a source of serious disagreement between the British and the Arabs, and later of course between the Jews and the Arabs, is Jerusalem.) It was only with great reluctance that the Arabs had allowed the British to open a consulate in Jidda (the Union Jack flying there was a particular grievance, since it consists of a cross in three different forms), and on the occasions when it was necessary for the sharif’s sons to meet with an Englishman, they rode down from Mecca to Jidda, a distance of about forty-five miles, to do so. Mecca was, and remains today, a city closed to infidels. As for their father,the sharif preferred to remain in Mecca whenever possible, communicating with his British ally by long, opaque, and often bewildering letters in Arabic, and from time to time by telephone to Jidda, for surprisingly there was a telephone system in the holy city; his own number was, very appropriately, Mecca 1.

After a walk from the harbor through the fly-infested open stalls of the food market in the oppressive heat, Storrs and Lawrence were happy enough to be shown into a shaded room in the British consulate, where they were awaited by the British representative in Jidda, Lieutenant-Colonel Cyril Wilson, who disliked both his visitors: he did not trust Storrs, and he had argued with Lawrence in Cairo about the appropriateness of British officers’ wearing Arab clothing. “Lawrence wants kicking and kicking hard at that,” Wilson wrote, adding, “He was a bumptious young ass,” though Wilson would soon change his mind, and become one of Lawrence’s supporters. Lawrence’s opinion of Wilson, though he would tone it down in later years when writing Seven Pillars of Wisdom, was at first equally critical—critical enough so that Storrs prudently censored it out of his account of the meeting. Part of Wilson’s resentment at Lawrence’s presence was that it was unclear to him what Lawrence was doing there; the rest no doubt was a result of Lawrence’s personality, which older and more conventional officers found trying at the best of times.

In fact Lawrence’s presence was not, as he later suggested, “a holiday and a joy-ride,” a pleasant way of using up a few days of leave sightseeing in the congenial company of Storrs. Management and control of the Arab Revolt were shared among a bewildering number of rival agencies and personalities, each with its own policy: the British high commissioner in Egypt, the commander in chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, and the Arab Bureau, in Cairo; military intelligence in Ismailia, halfway between Port Said and Suez; the War Office, the Foreign Office, and the Colonial Office, in London; the government of India, in Delhi (the largest body of Muslims in the world was in India and what is now Pakistan); and the governor-general of the Sudan, in Khartoum, since the shortestsupply route to the Hejaz was across the narrow Red Sea, from Port Sudan to Jidda. Colonel Wilson was, in fact, the representative in Jidda of a larger-than-life imperial figure, General Sir Reginald Wingate Pasha, GCB, GCVO, GBE, KCMG, DSO, the fiery governor-general of the Sudan, an old and experienced Arab hand who had fought under Kitchener and had known Gordon of Khartoum. Storrs, a diplomat, was the adviser of Sir Henry McMahon, the high commissioner of Egypt. Lawrence’s immediate superior was Brigadier-General Gilbert Clayton, who, like Wingate and Storrs, was another of Kitchener’s devoted disciples. Until recently Clayton had been serving as director of all military intelligence in Egypt, and as Wingate’s liaison with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force and chief of the newly formed Arab Bureau.

Lawrence admired Clayton, and would later describe him as “like water, or permeating oil, soaking silently and insistently through everything,” which is probably the best description of how an intelligence chief ought to operate. Clayton appears to have had no great confidence in the ability of Storrs, a mere civil servant, to judge men and events, especially in the military sphere; but he had come to respect Lawrence’s judgment, and to rely on his well-informed reports about affairs in the Ottoman Empire. It was not therefore Storrs who was “babysitting” Lawrence, but Lawrence who was babysitting Storrs, though Storrs may not at first have realized the fact.

Given the number of conflicting agencies involved in the Arab Revolt, it is hardly surprising that British policy was inconsistent. Most of the older members of the war cabinet in London were, or had been, by instinct and habit Turcophiles; for throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries support for the Ottoman Empire—however devious, corrupt, and incompetent the sultans may have been—was a cornerstone of British foreign policy. Turkey was the indispensable buffer between imperial Russia and the Mediterranean—Russia’s undisguised ambition to seize Constantinople and dominate the Near East and the Balkans concerned British statesmen almost as much as its relentless advance south toward Afghanistan. In the west, Russia’s ambition would threatenthe Suez Canal; in the south it threatened India, still the “jewel in the crown,” the largest and most valuable of British colonial possessions. Hence, propping up Turkey, the “sick man of Europe,” as Czar Nicholas I* is said to have referred to the Ottoman Empire, was thought to be a vital British interest. Those who still believed this—and there were many—were not well pleased by the fact that bumbling diplomacy on the part of Great Britain in 1914, and greed and duplicity on the part of Turkey, had brought Turkey into the war on the side of the Central Powers, while Russia was now an ally of the British. Enthusiasm for an Arab revolt was, as a result, always equivocal in London, while in Delhi there was outright opposition and obstructionism for fear that a successful Arab revolt would inspire similar ambitions among the hundreds of millions of Muslims in India. Support for an Arab revolt centered on the powerful figure of Field Marshal Kitchener until his death at sea in June 1916, but survived among those of his acolytes who remained in the Middle East, and also a few powerful political figures in London, particularly David Lloyd George, who had replaced Kitchener as secretary of state for war and would shortly replace an exhausted Asquith as prime minister. The actual Arab Revolt had been going on since the summer of 1916, but Storrs, who was deeply involved in the diplomatic side, was not alone in criticizing the “incoherent and spasmodic” quality of the leadership to date, or in longing for “a supreme and independent control of the campaign,” which he had hoped to find in Aziz Ali Bey el Masri, Sharif Hussein’s chief of staff.