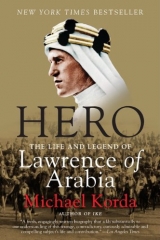

Текст книги "Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia "

Автор книги: Michael Korda

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 55 страниц)

Years later, after Lawrence had died, Storrs wrote in Orientations: “None of us realized then that a greater than Aziz was already taking charge.”

That Lawrence might be the leader Storrs had in mind was certainly not immediately evident, at any rate to Wilson, but rapidly became more so with the arrival in Jidda, from Mecca, of Emir Abdulla, mounted on a magnificent white Arabian mare, and accompanied by a large and colorful retinue. Abdulla, the object of Storrs’s visit, was short, rotund, and animated, but an impressive figure all the same, wearing “a yellow silk kuffiya, heavy camel’s hair aba, white silk shirt,"* the whole effect spoiled only, in Storrs’s opinion, by ugly Turkish elastic-sided patent leather boots. Abdulla was a good part of the reason for the tension between Storrs and Wilson, apart from the natural mistrust between a civil servant and a professional soldier, for they were obliged to inform him that many, indeed most, of the things his father had been promised would not be forthcoming, a task that was uncongenial to them both. The most important among these was a flight of fighter aircraft from the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) to deal with the Turkish aircraft, which had been supplied by Germany and, like most modern war equipment, were having a disproportionate effect on the morale of the Bedouin tribesmen who made up the majority of the Arab forces. The plan had been to station the RFC aircraft about seventy-five miles north of Jidda in Rabegh, with a brigade of British troops to guard them. This plan was reversed at the last minute by General Wingate in Khartoum—the RFC would not send the planes without British troops, but the question of stationing a British brigade in the Hejaz was a political hot potato, since the Arabs were likely to resent the presence of foreign Christian troops in their Holy Land as much as they resented that of the Turks—or possibly more, since the Turks were at least Muslims.

In the course of the lengthy discussions—Abdulla was a born diplomat, who would go on to become the first king of Jordan, and would die in the Dome of the Rock mosque in Jerusalem in 1951, assassinated by a Palestinian fanatic who believed the king was planning to make a separate peace with Israel—both Wilson and Storrs seem to have allowed the young staff captain to take over, since he clearly knew his facts. “When Abdallah* quoted Feisal’s telegram,” Storrs wrote, “saying that unless the two Turkish aeroplanes were driven off the Arabs would disperse: ‘Lawrence remarked that very few Turkish aeroplanes last more than four or five days…. ‘ ‘Abdallah was impressed with Lawrence’s extraordinary detailed knowledge of enemy dispositions’ which, being … temporarily sub-lieutenant in charge of ‘maps and marking of Turkish Army distribution,’ he was able to use with masterly effect. As Syrian, Circassian, Anatolian, Mesopotamian names came up, Lawrence at once stated exactly which unit was in each position, until Abdallah turned to me in amazement: ‘Is this man God, to know everything?’ ”

Despite Lawrence’s dazzling display of knowledge, at the same time he took the opportunity to carefully appraise Abdulla. In fact, the primary purpose of his “holiday” was to report back to General Clayton in Cairo on Sharif Hussein’s sons, and to give a firsthand appraisal of which one of them the British should back as the military leader of the revolt. Secondarily, he was to appraise Storrs and Wilson for Clayton’s benefit, a function of which his two hosts were happily unaware. Lawrence had a certain respect for Wilson as an administrator, and a trusted link with Sharif Hussein, but he soon came to the conclusion that Abdulla, although superficially charming, was not the leader the British were looking for, still less the man that Lawrence himself was searching for. Abdulla, he would write, “was short, strong, fair-skinned, with a carefully trimmed brown beard, a round smooth face, and full short lips…. The Arabs thought Abdulla a far-seeing statesman, and an astute politician. Astute he certainly was, but I suspected some insincerity throughout our talk. His ambition was patent. Rumor made him the brain of his father, and ofthe Arab Revolt, but he seemed too easy for that…. My visit was really to see for myself who was the yet unknown master-spirit of the affair, and if he was capable of carrying the revolt to the distance and greatness I had conceived for it: and as our conversation proceeded I became more and more sure that Abdulla was too balanced, too cool, too humorous to be a prophet, especially the armed prophet whom history assured me was the successful type in such circumstances.”

No doubt Abdulla, who, behind a jovial and good-natured facade, was a shrewd judge of men, divined something of Lawrence’s reservations about him, both in Wilson’s hot little room at the consulate and later on, in Abdulla’s sumptuously appointed tent outside Jidda. The interior of this tent was decorated with brightly colored silk-embroidered birds, flowers, and texts from the Koran; it was placed near the green-domed shrine that was reputed to be the burial place of Mother Hawa, as Muslims call Eve, where Abdulla had pitched his camp in the hope of avoiding the fever that was reported in town. He may also have been sensitive enough to guess that young Lawrence was not only a potential man of action, but something even more dangerous: a man of destiny.

In any case, the relationship between the two men, while polite, would never be close. Even though Lawrence was at least partly responsible for securing for Abdulla after the war the throne of what was then called Trans-Jordan, Abdulla in his memoirs—published in 1950, only a year before his own assassination—belittled Lawrence’s role in the Arab Revolt, and complained of “the general dislike of Lawrence’s presence” among the tribes. Rather reluctantly, however, he eventually agreed to Lawrence’s request to venture inland to meet two of Abdulla’s brothers, Emir Ali and Emir Feisal, though Storrs had to call their father, Sharif Hussein, in Mecca before Abdulla was authorized to prepare the necessary letter. The hesitation was less from a desire to prevent this inquisitive and well-informed young Englishman from observing the real state of the sharif’s armies in the field—though this thought may have crossed Abdulla’s mind—than from the sensible fear that once Lawrence was out of Jidda, as a European and Christian he was very likely to be murdered,or that in his khaki uniform he could be mistaken for a Turkish officer, and murdered on that account. On Storrs’s first trip to the Hejaz in 1914 one of the sharif’s aides had offered to sell him for Ј1 the severed heads of seven Germans who had been murdered that week in the hinterland, and strong feelings on the subject of infidels near the holy places had not lessened since then among the Bedouin, despite the fact that the British and the French were now their allies.

Such stories as these merely spurred Lawrence on. It is unclear from the somewhat conflicting accounts of Storrs and Lawrence why Storrs was willing to deploy on Lawrence’s behalf his considerable powers of persuasion against the sharif to make possible a journey of considerable danger that, so far as he knew, nobody in Cairo had ordered or authorized Lawrence to make, but very likely he bowed to what he already recognized was a stronger will. Besides, nobody at Jidda or in Cairo seemed to know what was going on at Rabegh, let alone in the desert beyond it, and Lawrence’s proposal to go and find out for himself may have seemed daring, but sensible. As for Lawrence, he did not bother asking for permission; he simply sent a telegram to Clayton that began: “Meeting today: Wilson, Storrs, Sharif Abdallah, Aziz el-Masri, myself. Nobody knows real situation Rabugh so much time wasted. Aziz al-Masri going Rabugh with me tomorrow."*

So began the adventure.

Lawrence traveled to Rabegh by ship with Storrs and Aziz el Masri, on a rusty, wallowing old tramp steamer; there they transferred to a more comfortable Indian liner anchored in the harbor. On board the liner they were joined by Emir Ali, the sharif’s eldest son, for three days of discussion in a comfortably carpeted tented enclosure on deck, during the course of which Ali repeated at great length the same requests for more gold, guns, and modern equipment that his brother had made at Jidda,but with less force and less humor. Closer to the fighting, his view of the situation was less optimistic than Abdulla’s—his brother Feisal, with the bulk of the Arab army, was about 100 miles to the northeast, encamped in the desert, still licking his wounds from the failure of the attack on Medina, and hoping, if possible, to prevent a Turkish advance on Mecca or Rabegh. Ali reported that “considerable” Turkish reinforcements were arriving in Medina from Maan, that the Arab army needed artillery like that of the Turks, and that his brother Feisal was hard pressed; but as Storrs was to note later, there was in fact no reliable means of passing intelligence from Feisal in the field to Ali in Rabegh or from there to Jidda and Mecca, let alone anybody to assess the reliability of the information, and act on it.

Lawrence liked Ali at once, in fact “took a great fancy” to him and praised his dignified good manners, but at the same time reached the conclusion that Ali was too bookish, lacked “force of character,” and had neither the health nor the ambition to be the “prophet” Lawrence was looking for. As for Ali, he was “staggered” by his father’s instruction to send Lawrence up-country, but once having expressed his doubts about the wisdom of it, he gave in gracefully. To all Sharif Hussein’s sons, their father’s word was law. By the time Storrs departed on the same hideous, crowded tramp steamer that had brought them—it had no refrigerator, electric lights, or radio, and on board the principal food was tinned tripe—for the long, slow return journey to Suez, often into a “very fierce” gale, Lawrence’s arrangements were already made. Ali had graciously offered Lawrence his own “splendid riding camel,” complete with his own beautiful, highly decorated saddle and its elaborate trappings, and had chosen, to accompany Lawrence, a reliable tribesman, Obeid el Raashid, together with Obeid’s son. Years later, Storrs could still remember the sight of Lawrence standing on the shore in the pitiless sun, “waving grateful hands” as Storrs’s tramp steamer raised anchor.

Lawrence’s decision to travel into the interior of the Hejaz was undertaken at a critical moment for the Arab Revolt. Ever since June 1916, when Sharif Hussein, after much hesitation and endless bargaining with the British, had finally made the decision to rebel against the Turkish government, he had relied on two separate forces. The first force (usually referred to as “the regulars”) consisted of Arab prisoners of war or deserters from the Turkish army, more or less disciplined and uniformed, and commanded by Arabs who for the most part had been officers in the Turkish army. Of these officers, the two most prominent for the moment were Aziz el Masri, an experienced professional soldier who was the sharif’s chief of staff; and Nuri as-Said, an Arab nationalist from Baghdad who was both a political and a military workhorse. The second, and much larger and more colorful, armed force was drawn from those Bedouin tribes that had been moved by British gold, the hope of plunder, loyalty, or blood ties (however slender) to the sharif of Mecca—or, more rarely, by nascent Arab nationalism—to join in the struggle. Some of these Bedouin were under the more or less lackadaisical command of Emir Ali at Rabegh, but the majority were under the command of Ali’s younger and more inspiring brother, Emir Feisal. Since the beginning of the revolt the British had contributed quantities of small arms and gold sovereigns (the Arabs, from the sharif himself down to the lowliest tribesman, would do nothing without advance payment in gold), machine guns, ammunition, naval support, food supplies, and military advice, without much to show for it so far, except the sharif’s refusal to join the jihad. Sharif Hussein had managed to capture and hold on to Mecca, and after a siege had taken nearby Taif. But the Arab attack on Medina, the last station on the railway line from Damascus, 280 miles to the north of Mecca, had failed dismally; the Arabs were driven back by the steady discipline of the entrenched Turks and by well-sited modern artillery.

Medina had made it apparent that the Bedouin levies were unprepared for modern warfare, and easily panicked by modern weapons like artillery and airplanes; nor did they lend themselves to the discipline and organization of a modern army. If they obeyed anyone, the men obeyed their tribal leader, or sheikh, and all the men were equal—they had no concept of a chain of command, no such thing as noncommissionedofficers, and no understanding of Kadavergehorsam,* the reflexive obedience to an order that was pounded into trained infantry on the parade ground in every army in Europe. Since their primary loyalty was to tribe, clan, and family, the heavy casualties of modern warfare were unacceptable to the tribesmen—they were brave enough, and could be inspired (though never ordered) to perform daring acts; but each death in their ranks was a grievous personal loss, not a statistic, and they came and went as they pleased. If a man felt the need to go home and tend to his camels or goats, he would leave and perhaps send back a son or a brother with his rifle to take his place. It was not, in brief, an army that could stand up to the Turks on equal terms in sustained attack on fixed positions; nor was it an army that British officers understood or trusted.

Since the British were paying for the Arab armies by the head, there was also a natural tendency on the part of Sharif Hussein and his sons to inflate the number of their troops, aggravated by the Arabic tendency to use the word “thousands” as a synonym for “many"; thus to this day the number of Arabs actually fighting in the revolt is unclear. Hussein claimed he had 50,000 fighters but admitted that only about 10,000 of them were armed; the Arab “regulars” may have numbered 5,000. Feisal’s army in 1917 consisted of about 5,000 men mounted on camels, and another 5,000 on foot. (A good many of these men on foot may have been unarmed servants, or slaves, for slaves, mostly blacks from the Sudan, were still commonplace throughout Arabia; indeed there was a rumor that one member of the French mission to Jidda had bought une jeune nйgresse, or a fair-skinned Circassian, “for a very reasonable price.”) In the Hejaz the Arabs certainly outnumbered the Turks, of whom there were about 15,000; but the Turks were by comparison a disciplined, modern force, with trained NCOs and an officer corps (aided by German and Austro-Hungarian advisers and military specialists), for the most part holding well-fortified strongpoints—a position not so very different (terrain and climate apart) from that of the U.S. Army in Vietnam.

Two keys to warfare in the region were the single-line Hejaz railway, the vital supply line connecting Medina to Damascus; and the location of wells, which determined the line of any advance in the desert.

A third and most indispensable key—and the only one over which the British had any direct control—consisted of the ports along the Red Sea, which rose like the rungs of a ladder one by one up the coast of the Hejaz from Jidda in the south to Aqaba in the north. Rabegh, which was in British hands, was about seventy-five miles north of Jidda by sea; Yenbo, more precariously in Arab hands, about 100 miles north of Rabegh; Wejh (still in Turkish hands) about 200 miles north of Rabegh; and Aqaba nearly 300 miles north of Wejh. Inland, past Aqaba to Yenbo, the Hejaz railway ran about fifty miles distant from and more or less parallel to the coastline behind a formidable barrier of rugged mountains, until it ended in Medina. This configuration made the railway vulnerable to small parties who knew their way through the mountains, but also meant that the Turks had the means to quickly transfer troops from Medina or from Maan to threaten any of the ports held by the British and the Arabs. It was the guns of British warships that made such an attack risky; and the support of the Royal Navy (as well its ability to bring in a constant stream of supplies, equipment, and gold) was the major factor keeping the Arab Revolt alive.

For all that, the war in the Middle East was going badly. Attempts by the British to break through the Turkish line at Gaza had failed; the Arabs’ attempt to take Medina had led merely to a protracted and humiliating defeat; and the Arabs’ hostility toward any European presence inland meant that nobody in Cairo had a clear picture of just what Feisal’s men were doing, or what was taking place in the vast, empty desert beyond the few small ports on the Red Sea in the possession of the Allies.

Emir Ali insisted that Lawrence leave after dark, so none of the tribesmen camped in Rabegh would know that an Englishman was riding into the interior; for the same reason, he provided Lawrence with an Arab head cloth and cloak as a disguise. The kufiyya, or head cloth, held aroundthe head by a knotted agal of wool, or in the case of persons of great importance finely braided gold and colored silk thread, was (and remains) the most distinctive item of Bedouin clothing. The pattern of the cloth and the color of the agal usually identify one’s tribe, so they also serve to identify friend and foe. The Bedouin disliked the sight of European peaked caps and sun helmets, finding them at once blasphemous and comic. The sun helmets seemed all the more comic because the few British officers who adopted the kufiyya (which was convenient and protective in the desert) usually wore it over the bulky khaki solar topee, making a grotesque and ludicrous display of themselves before the natives. What looked like a huge cloth-covered beehive on the head was funnier still when the wearer was bobbing up and down on a camel. Lawrence avoided this from the first, in the interest of providing an identifiably Arab silhouette in the moonlight—besides, he had often worn a kufiyya while working in the desert as a young archaeologist before the war, and found nothing strange about it. It was cool and sensible: it protected the wearer from the sun, the loose ends could be tied around the face against wind and sandstorms, and it did not provoke the hostility of the tribesmen.

Emir Ali and his half brother Emir Zeid, the youngest of Hussein’s sons, came down to see Lawrence off, in a date palm grove on the outskirts of the camp. No doubt they had mixed emotions: neither of them can have relished being responsible for Lawrence’s safe journey. Ali also disliked from the start the whole idea of Lawrence’s journey to see Feisal, which offended his strong religious sensibilities. However, Zeid, still a “beardless” young man, was not shocked or outraged at all—his mother was Turkish, and as the third of Hussein’s three wives was a relative newcomer to the harem, so Zeid had neither Ali’s intense religious feelings, nor his father’s and half brothers’ attachment to the Arab cause; indeed Lawrence at once judged him insufficiently Arab for his purposes.

Neither Obeid nor his son carried any food with them—the first stage of their journey was to Bir el Sheikh, where Ali said they might pause for a meal, about sixty miles away; no Arab thought a journey of such a short distance required food, rest, or water. As for riding a camel, though itwas not Lawrence’s first attempt, he made no pretense of being a good or experienced rider. Unlike most Englishmen of his class and age, he was not an experienced horseman—his family’s budget had not extended to riding lessons; he and his brothers had excelled at bicycling, not horsemanship. Nor had he ever covered this kind of distance on a finely bred camel, which paced, in long, undulating strides, while the rider sat erect as in a sidesaddle, with the right leg cocked over a saddle post, and the left in the stirrup. Two years of desk work in Cairo had not prepared Lawrence for the fatigue, the saddle sores on legs unused to riding, the backache, the suffocating heat, or the monotony of riding by night, often over rough ground. Sometimes he dozed off—neither Obeid nor his son was a talker—and woke with a start to find himself slipping sideways, saved from a fall only by grabbing the saddle post quickly.

He had no fears about his companions—it was an extension of the Arab belief in the obligation of hospitality toward a guest as an absolute duty that those charged with conveying a stranger must protect him with their lives, whatever they thought of him. But Obeid was a Hawazim Harb, and the Harbs surrounding Rabegh were hardly more than lukewarm on the subject of the sharif of Mecca; also, their sheikh was known to be in touch with the Turks. Then too, as Lawrence knew from his experiences traveling, mostly on foot, through Palestine, the Sinai, and what is now Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria—where, as a young archaeologist he had separated armed, warring factions among the workers at the dig—the blood feud was an unavoidable part of Arab life. It involved not just tribe against tribe, but feuding within clans and families and between individuals—no matter how peaceful a situation might seem, you could never be protected from sudden, unexpected violence that might also engulf the stranger.

Empty, vast, and unprofitable as the desert looked to Europeans, every barren square foot of it, every wadi, every steep rocky hill, every sparse patch of thornbush, every well—however disgusting the water—was claimed by some tribe or person and would be defended to the death against trespassers. Nor was “the desert” a romantic, endless landscapeof windblown sand dunes: much of it was jagged, broken, black volcanic rock, as sharp as a razor, and fields of hardened lava that even camels had difficulty crossing. Steep valleys zigzagged to nowhere; towering, knife-edged hills rose from the sand; flat patches of bleached, glassy sand, the size of some European countries, reflected the harsh sunlight like vast mirrors at 125 degrees Fahrenheit or more, and stretched to the horizon, broken only by sudden sandstorms appearing out of nowhere. Except for remote areas where a green fuzz of short, rough grass in the brief “rainy season” was counted as rich pasturage for the great herds of camels that were the principal source of wealth for the Bedouin tribes, this was the landscape, or close to it, of Cain and Abel, of Joseph sold into slavery by his brothers, of Job—it was not a safe or kindly place to be.

Lawrence’s mind was on the fact that the path they were following was the traditional route by which pilgrims traveled from Medina to Mecca—indeed, in the Hejaz a large part of the Arabs’ feeling against the Turks came from the building of the railway from Damascus to Medina, since the Bedouin earned money by providing guides, camels, and tented camps for the pilgrims along the desert route (and also from robbery and shameless extortion at their expense). It was the local Bedouin’s ferocious hostility to this modern encroachment that had so far prevented the Turks from building a planned 280-mile extension of the railway from Medina all the way to Mecca. Lawrence, as his camel paced in the moonlight from the flat sand of the coast into the rougher going of scrub-covered sand dunes marred by potholes and tangled roots, meditated on the fact that the Arab Revolt, in order to succeed, would have to follow the “Pilgrim Road” in reverse, as he was doing, moving north toward Syria and Damascus, bringing faith in Arab nationalism and an Arab nation as they advanced, as the pilgrims brought their faith in Islam yearly to Mecca.

Perhaps in deference to the fact that he was an Englishman, not an Arab, his guides called a halt at midnight, and allowed Lawrence a few hours of sleep in a hollow in the sand, then woke him before dawn to continue, the road now climbing the length of a great field of lava, againstwhich pilgrims for untold generations had left cairns of rocks on their way south, then across a wide area of “loose stone,” then on and upward until at last they reached the first well of their journey. They were now in territory controlled by the local tribes, who favored the Turks, or whose sheikhs received payment from the Turks, and reported on the movement of strangers.

No well on a much-used route like this one was ever likely to be deserted—a well was the Arab equivalent of a New England village store—and with good reason Ali had warned Lawrence strictly against talking to anyone he might meet along the way. Neither then nor later did Lawrence ever try to pass himself off as a native—his Arabic was adequate, but in each area of the Ottoman Empire, and beyond, it was spoken differently, and both his speech and his appearance marked him out as a stranger—not necessarily an Englishman, because his fair coloring and straight, sharp nose were not uncommon among Circassians, but certainly not a Bedouin.

Anything but a lush oasis, the well was a desolate place, surrounded by the remains of a stone hut, some rude “shelters of branches and palm leaves,” and a few shabby, ragged tents. A small number of Bedouin watched after their camels from a distance as Obeid’s son Abdullah climbed down into the well and brought up water in a goatskin, while his father and Lawrence rested in the shade.

Lawrence seems to have attracted no attention, even when a group of Harb tribesmen driving a large herd of camels arrived, followed, perhaps more dangerously, by two richly dressed young men riding thoroughbred camels: a sharif and his cousin disguised as a master and servant to pass through the country of a hostile tribe undisturbed. This pair might at least have been expected to express some curiosity about the presence of a stranger at the well, but Lawrence seems to have possessed a natural gift for remaining silent and motionless, without betraying himself—he had always been fearless; from boyhood on he had deliberately cultivated indifference to danger and hardship, as well as emotional independence, as if rehearsing for the role he was about to play, and his lack of fearsomehow communicated itself to others in the sense that they felt he belonged where he was, whoever he might be.

In some ways, this was more effective than a vulgar disguise—the real Lawrence was actually less noticeable than if he had tried to darken his skin and pretend to be an Arab, like Sandy Arbuthnot, a character in John Buchan’s classic adventure novel Greenmantle, who many believe was based in part on Lawrence. It was something of a skill, the equivalent of camouflage or protective coloration. As a junior staff officer Lawrence had sat unnoticed among vastly more senior officers in meetings where he had no business to be, without attracting attention to his presence until he spoke (at which point, he usually dominated the conversation); he did the same among the Bedouin. His individualism—and later his curious combination of fame and shyness—gave people the impression that he never “belonged” anywhere, but he had the great actor’s gift for playing whatever role was presented to him. It was then not yet apparent that the role of a hero would come to him more easily—and stick to him much longer—than any other.

In any case, unquestioned, Lawrence and his guides continued on through an increasingly difficult and barren landscape, which gradually gave way to fine white sand that radiated the heat and the glare of the sun until he had to close his eyes against it. In the distance were fantastic rock formations and jagged mountains. They had left the roadway, such as it was, to track across country for hours, and rejoined it just as the sun began to set. Bir el Sheikh, when they reached it, proved to be nothing more than a tiny cluster of “miserable” rock huts on either side of the way, from which the smoke of cooking fires arose. Obeid dismounted and bought flour; and this was the end of the first stage of their journey.

Lawrence describes, with the eye of a good travel writer, how Obeid mixed the flour with a little water and patted and pulled it into a disk about “two inches thick, and six inches across,” which he plunged into the embers of a brushwood fire to bake, and which the three of them shared after Obeid had clapped it between his hands to knock the cinders off. Lawrence’s indifference to food was notorious, and he had nodifficulty surviving on the usual Bedouin rations of flour and dates. (It was their rare feast that made him queasy: a whole sheep—cooked with head, innards, and all—served on an enormous copper tray in a thick bed of rice moistened with hot grease.)

An hour to cook and eat their meal, an hour of rest, and they were on their way again, in pitch darkness, on fine sand so soft that Lawrence at first found the silence oppressive. Along the way, perhaps because Lawrence blended in so well with the Bedouin way of life and made none of the complaints and demands that might be expected from a British officer, Obeid had become more talkative, and even gave Lawrence a few tactful hints about how to get the best out of his camel. Obeid had already indicated to Lawrence the existence of a small village of date farmers only a few hours from Rabegh, and of another settlement farther on along a valley that would give the Turks an opportunity of flanking Feisal’s army and attacking Rabegh, or, alternatively, marching south from well to well to isolate Rabegh and attack Mecca. Neither Emir Abdulla nor Emir Ali had thought to mention this interesting feature of the topography around Rabegh, which Lawrence instantly realized made the idea of placing a British brigade there both risky and pointless. Hitherto, whenever Sharif Hussein had been alarmed by signs of a Turkish advance, he had requested the immediate dispatch of a brigade, while the British had hesitated, unwilling to commit troops when so many were needed elsewhere; but whenever the British, alarmed by events in the Hejaz, had offered a brigade, the sharif had always turned it down at the last minute, saying that his people would object to the presence of Christian soldiers. Now it was clear to Lawrence that placing a British brigade in Rabegh would be useless, even in the unlikely event that General Wingate agreed to provide one, and at the same time, Sharif Hussein agreed to accept it.