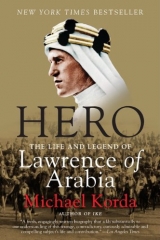

Текст книги "Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia "

Автор книги: Michael Korda

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 49 (всего у книги 55 страниц)

Catchpole flagged down a passing army lorry, and ordered the driver to take Lawrence and one of the boys, who had sustained minor injuries, to the Bovington camp hospital, the nearest medical facility, where Lawrence was quickly identified. After that the army took control, although Lawrence was a civilian and the accident had taken place on a civilian road. All ranks were warned that they were not to talk to newspapermen, and reminded that they were subject to the Official Secrets Act; newspaper editors were informed that bulletins about Lawrence’s health would be issued by the War Office. As anyone could have predicted, this had the effect of increasing interest in Lawrence’s crash, adding a note of mystery to what was simply a tragic road accident. Even without that, however, it was a major news story throughout the world. Arnold Lawrence was informed of the accident by the Cambridge police, and arrived the next day at Clouds Hill with his wife.

Lawrence lay unconscious in the hospital at the army camp he had disliked so much when he was exiled from his beloved RAF. Distinguished specialists in brain injuries were sent for; the king dispatched two of his own physicians, including the future Lord Dawson of Penn, and telephoned himself, asking to be kept informed. The Home Office, not wanting affairs left entirely in the hands of the military, sent two plainclothes officers from Scotland Yard, one to sit in Lawrence’s room, while his relief slept on a cot outside in the corridor. To be fair, this was probably less from any fear of foreign agents or security issues than to prevent an enterprising newspaper photographer from finding a way in to take a picture of Lawrence on his deathbed.

Everything that could be done was done, given the limited facilities of the Bovington camp hospital; but as the doctors had concluded after examining Lawrence, the case was hopeless.

Lawrence lingered six days, never regaining consciousness, with his lungs becoming increasingly congested, and died just after eight in the morning on Sunday, May 19.

He was forty-six years old.

Postmortem examination revealed that Lawrence would have lost his memory and would have been paralyzed had he survived.

He was buried in the nearby churchyard of Moreton. His old friend Ronald Storrs (now Sir Ronald, and governor of Cyprus) was the chief pallbearer. The others were the artist Eric Kennington; Colonel Stewart Newcombe, who had known Lawrence since the Sinai survey before the war; a neighbor; and two service friends of Lawrence’s, one from the army and the other from the RAF.

The small ceremony was quiet, despite a mob of photographers and reporters, and many of Lawrence’s friends were present: Winston Churchill and his wife, Lady Astor, Mrs. Thomas Hardy, Allenby, Siegfried Sassoon, Lionel Curtis, Augustus John, Wavell, Alan Dawnay. As the coffin was lowered into the ground the soldier and the airman, on opposite sides of the grave, shook hands over it; and at the last moment a neighbor’s little girl ran forward and threw a bunch of violets on the top of it.

Nancy Astor, in tears, ran to put her arms around Churchill, who was also in tears, and cried, “Oh, Winnie, Winnie, we’ve lost him.”

The king’s message to Arnold Lawrence would appear the next day in the Times:

The King has heard with sincere regret of the death of your brother, and deeply sympathizes with you and your family in this sad loss.Your brother’s name will live in history, and the King gratefully recognizes his distinguished services to his country and feels that it is tragic that the end should have come in this manner to a life still so full of promise. Perhaps fortunately, because of his gifts of description, Ronald Storrs—who had taken the young Lawrence with him on his journey to Jidda in 1916, and had watched him wave good-bye from the shore at Rabegh, the day before his ride up-country to the meeting with Feisal and, in Storrs’s words, to “write his page, brilliant as a Persian miniature, in the History of England"—was the last to see him before his burial.

I stood beside him lying swathed in fleecy wool; stayed until the plain oak coffin was screwed down. There was nothing else in the mortuary chamber but a little altar behind his head with some lilies of the valley and red roses. I had come prepared to be greatly shocked by what I saw, but his injuries had been at the back of his head, and beyond some scarring and discolouration over the left eye, his countenance was not marred. His nose was sharper and delicately curved, and his chin less square. Seen thus, his face was the face of Dante with perhaps the more relentless mouth of Savonarola; incredibly calm, with the faintest flicker of disdain…. Nothing of his hair, nor of his hands was showing; only a powerful cowled mask, dark-stained ivory against the dead chemical sterility of the wrappings. It was somehow unreal to be watching beside him in these cerements, so strangely resembling the aba,the kuffiyaand the agalof an Arab Chief, as he lay in his last littlest room, very grave and strong and noble. His plain, modest headstone merely describes him as “T. E. Lawrence, Fellow of All Souls College,” as if even in death he was still resisting the rank of colonel and all his decorations. Below are inscribed the words:

The hour is coming & now isWhen the dead shall hearThe Voice of theSON OF GODAnd they that hear shall live. They were placed there, we may be sure, to please his mother, rather than from any wish of Lawrence’s, who was at best a nominal Christian. At the foot of the grave is a smaller stone, in the shape of an open book, bearing the words ”dominus illuminatio mea,” which may be translated “The Lord is my light,” but which can also mean “May God enlighten me.”

The open book and the Latin phrase form part of the heraldic coat of arms of Oxford University, and it is perhaps the most fitting memorial to Lawrence, who grew up among the ancient walls and towers of Oxford, and whose character was formed by it more than by any other single element, perhaps the most extreme example of the scholar turned hero in the eleven centuries of its existence.

* A full set of equipment consisted of large pack, small pack, webbing belt, ammunition pouches, canteen and bayonet holders, rifle sling, and all the straps that held everything together; it had to be assembled in an exact pattern, brass buckles gleaming.

*Clare Sydney Smith would eventually write a touching book about her friendship with Lawrence, The Golden Reign.Nancy Astor (Viscountess Astor), the first woman member of Parliament, had a relationship with Lawrence that was certainly flirtatious—she was the only woman who rode pillion behind him on his motorcycle—but she was rather too formidable a personality to be described as a flirt.

* “Bus,” like “kite,” is RAF slang for an aircraft, particularly a multiengine bomber or transport, and by extension also a motor vehicle of any kind.

* Lawrence printed 128 “complete” copies (with all the illustrations) for the subscribers, as well as thirty-six complete copies and twenty-six incomplete copies (the latter lacking some of the illustrations) to give away to friends, plus twenty-two copies without plates and certain textual omissions to go to the George h. Doran Company in New York, some to secure U.S. copyright, others to be offered for sale at the prohibitively high price of $200,000 a copy (about $3.2 million in today’s money). of these copies, Lawrence kept six. ( Letters, 295, 466, quoted in hyde, Solitary in the Ranks.)

* Perhaps more than any other single title, Revolt in the Desertensured the survival and profitability of its U.K. publisher, Jonathan Cape.

* Lawrence had met robert Graves when Graves came up to Jesus College, oxford, as an undergraduate after the war (in which he had served with distinction as an infantry officer, and which he would later describe in Goodbye to All That). Graves had by then already achieved some fame as one of the British war poets, and he would go on to write more than 140 books before his death in 1985 at the age of ninety.

* By this time Lawrence had changed his name by deed poll to Shaw. Legally and officially he had abandoned the name which his father had chosen on leaving ireland, and which Lawrence himself had made famous. it made little difference, of course—to most of the world he remained and would always remain “Lawrence”—but it at least removed the objection of some officers to the fact that he was serving in the ranks under a false name.

* The figure of 5100,000 in 1927 would be about $1.6 million today; Ј5,000 would be about 5375,000.

* All this may sound familiar to the reader eighty-two years later.

*Those who favor this policy today (in much the same area where Lawrence was in 1928) should bear those doubts in mind. Whether by biplane or by drone, bombing people’s villages and killing their wives and children will inflame, not put down, an insurgency.

* The luxurious liners of the Peninsula & orient Steamship Company were the preferred way of traveling to and from Britain to the British colonies in the east; they played much the same role as the French Messageries Maritimes.

* Lawrence was embarrassed by the excessive generosity of this gift, even though it turned out that some of his wealthy friends, like Buxton and Curtis, had also contributed toward it, and in the end decided to pay for it himself. Buxton, ever the astute banker, had managed to get Brough to agree to a discount (Lawrence was his most famous customer), so the final price was ₤144 four shillings and sixpence (₤144/4s/6d),or about $7,500 in today’s money.

*The author was stationed for a time in the early 1950s at the Joint Services School for Linguists in Bodmin, Cornwall, about thirty miles northwest of Plymouth, and frequently quently rode his motorcycle up to London for the weekend in under six hours; he can vouch for the fact that on the roads in existence before the motorways were built, Lawrence was pushing it.

* At that time (and up until 1940) any large formation of aircraft was known in every air force in the world as a “Balbo,” after the spectacular long-distance, large-formation flights Balbo had led to publicize italy’s aviation strength.

* The Schwerpunktwas the central aim of German strategy, the focal point against which must be directed the maximum concentration of force to effect a breakthrough. The concept was characterized in World War ii by General Guderian’s comment,kleckern, klotzen!(“Don’t fiddle around, smash!”).

† London: Cassell, 1938.

*Alexander Korda (1893—1956) was the author’s uncle. Zoltan Korda (1895—1961) was the middle brother; and the author’s father, Vincent Korda (1897—1979), the youngest brother.

*Photographs of Clare Smith generally show her wearing a smart beret with a diamond brooch, not at all the kind of hat expected of a group captain’s wife in Singapore.

*To his credit, Baldwin did authorize expenditure on what would come to be called radar and on the eight-gun monoplane fighter (the Spitfire and the hurricane), but that was because they were presented to him in the most unobtrusive way by professionals he trusted. The task of “reorganizing” Britain’s defenses was not put into the hands of one person until April 1940, when Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, Baldwin’s successor, most reluctantly made Winston Churchill chairman of the Committee of Service Ministers and Chiefs of Staff, in addition to his post as first lord of the admiralty.

EPILOGUE

Life after Death

Lawrence is in the select group of heroes who become even more famous after death than they were while alive. The Library of Congress lists more than 100 books about him, of which fifty-six are biographical, and that number does not include several children’s books, two very successful plays, a major motion picture, and a television docudrama, as well as numerous Web sites devoted to his life and work. As Lawrence had feared, “the Colonel,” as he sometimes called his former self in a spirit of derision, just keeps marching on, despite every effort on Lawrence’s part to kill him off. Doubtless, if he had had his way, Lawrence would have been buried with the name T. E. Shaw inscribed on his headstone, but his brother Arnold stood firm in opposing that, and so it is as T. E. Lawrence that he lies in Moreton churchyard, and is commemorated by sculptures of various sizes in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral; at Jesus College, Oxford; at the City of Oxford High School; and in the tiny church of St. Martin’s, near Clouds Hill, where Eric Kennington carved a life-size recumbent effigy of Lawrence in his Arab robes and headdress, his hands crossed over his Meccan dagger as if in prayer, very similar to the medieval effigies of knights, crusaders, and their wives that Lawrence had photographed in his childhood.

The limelight that Bernard Shaw had warned him about has never dimmed, and he remains as famous now as he was seventy-five years ago, and perhaps even more controversial. In part this is because there exists a flourishing Lawrence cult, fueled by the Lawrence legend, that has kept an apparently endless number of controversies going on the subject of Lawrence, many of them created, not always inadvertently, by Lawrence himself. As early as 1929 he had predicted, in a letter to a friend, “I am trying to accustom myself to the truth that I’ll probably be talked over for the rest of my life: and after my life too.”

After Lawrence’s death his brother Arnold was bombarded by letters from admirers who saw Lawrence as the central figure of a new religion, in which they hoped Arnold might play the role of Saint Paul. Even before his death Lawrence was painted by “an Austrian-born religious artist named Herbert Gurschner” as a gently smiling, beatific religious figure in RAF uniform with a beggar’s cloak like that of Saint Francis thrown over his shoulders, against a lush background of Egyptian religious symbols. His left hand is raised in a kind of casual blessing, and through the long, graceful fingers of his right hand run grains of golden desert sand.

Arnold sensibly resisted attempts to make his brother a religious symbol or a martyr, but the impulse was already there to turn Lawrence into many things he had never been. He has been celebrated as an antiwar figure, although Lawrence’s feelings about war were ambivalent, to say the least. He has been made the hero of a novel portraying him as a thwarted homosexual who welcomes his own death, though nobody could have fought harder to be asexual than Lawrence, and there is no evidence that he wanted to die. He has been attacked as a total fraud and liar by one biographer, though the release of hitherto secret government files had by 1975 proved that Lawrence did everything he claimed to have done (and kept meticulous records), and that, if anything, he underplayed the importance of his role in the war and as Churchill’s adviser on Middle Eastern affairs after the peace. He has been blamed by the Arabs for the existence of Israel, and criticized by the Israelis as pro-Arab. Insurgents such as Mao, Ho Chi Minh, and Che Guevara have claimed to follow his methods of guerrilla warfare; but anti-insurgency fighters, such as the United States Army today, also claim to use his tactics. He sometimes gets a bad press as a sadist because of the killing of Turkish and German prisoners after the Arabs discovered the massacre of Arab civilians in Tafas, in 1918, and as a masochist because of the whippings meted out to him by John Bruce. He is criticized as an imperialist who wanted the new Arab states to be within the British Empire, and as an anti-imperialist who disliked Britain’s rule over India.

Lawrence as a religious cultfigure, with a pilgrim‘ s cape and sand running through his fingers. In the background, various mystical symbols. Painting by Herbert Gurschner, an Austrian-born religious artist, 1934.

Given the secrecy in which much of his life was passed, it is hardly surprising that some people refused to believe he was dead at all, and that according to persistent rumors he was recovering from his injuries in Tangiers, and would return whenever England was in danger. There were numerous “sightings” of him, usually in Arab dress, in the Middle East.

As the years passed, and the heroes of the Great War slipped from the public memory, Lawrence became one of the few people who couldbe remembered from that terrible war—a stand-in, as it were, for all the others. He had not been one of the young officers who had gone to their death unflinchingly, leading their platoons over the top into German machine gun fire; nor had he been one of the legion of faceless men, the PBI or “poor bloody infantry,” slogging through the mud and barbed wire. He was, in a curious way, classless; he had belonged to no regiment; he had fought according to his own rules; he was free from the cant and the naive patriotic enthusiasm that began to ring false to people in the 1930s; and he became, like Nelson, a pillar on which British patriotism rested, eccentric, perhaps, but undeniably a hero.

Even World War II did nothing to shake Lawrence’s reputation. On the contrary, his tactics were followed to the letter very successfully by the British Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) in Libya in 1941 and 1942: Seven Pillars of Wisdomwas their Bible, and Lawrence their patron saint. No less an authority than Field Marshal Rommel said, “The LRDG caused us more damage than any other unit of their size,” praise from the enemy that would not have surprised Lawrence. His influence remained strong: his old friend and admirer A. P. Wavell was in command of the Middle East; and Lawrence inspired a number of bold imitators, chief among them Major-General Orde Wingate, DSO and two bars—the son of General Sir Reginald Wingate, the sirdarof the Egyptian army who had recommended Lawrence for the “immediate award” of the Victoria Cross in 1917. Unorthodox, courageous, and a born leader, Orde Wingate applied Lawrence’s techniques, both in the Middle East and in Burma, with great success, becoming, like Lawrence, a great favorite of Churchill’s. Most military figures from World War I seemed irrelevant during World War II, but Lawrence’s reputation remained unscathed.

Lawrence’s literary reputation grew steadily. After his death Seven Pillars of Wisdomwas at last published in normal book form, using the text from the subscribers’ edition rather than preferred “Oxford version” of 1922; it sold more than 60,000 copies in the first year and went on to become a steady seller in English on both sides of the Atlantic, and in many other languages. (The Mintwas not published until 1955, and then it appeared in two versions: one expurgated and the other in a limited edition, with the barracks language intact.) The immense task of publishing Lawrence’s letters proceeded, and these won him perhaps even more praise than his books, for the sheer quantity and the quality of his correspondence was extraordinary. He was the subject, as well, of much careful scholarship. With both his flanks—military and literary—secure, Lawrence might have continued as a respected English hero, except that it would not have been in character for him to do that, dead or alive.

The great crisis in Lawrence’s reputation was caused by the publication in 1955 of Richard Aldington’s controversial Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry.Aldington had set out to write a conventional, admiring biography of Lawrence, at the suggestion of his publisher, but as he researched the book he discovered that he neither liked nor trusted Lawrence, and came to the conclusion that Lawrence had systematically twisted the facts to create his own legend.

Aldington’s book virtually destroyed his own health and his career as a writer. He was an odd choice for the thankless task of debunking Lawrence. He was not an investigative journalist, and he was far from being a mere crank; he was a respected, if minor, war poet, a novelist, a translator, a fairly successful biographer (of Voltaire, the duke of Wellington, and D. H. Lawrence), and a friend of such literary figures as D. H. Lawrence and Ezra Pound. A whole book has been written about Aldington’s attempt to deconstruct Lawrence’s legend—an attempt that began as a perfectly conventional exercise in biography rather than a deliberate attack on one of Britain’s greatest heroes. Aldington, a prickly, quarrelsome, difficult character, may not even have realized that when he set out to write about Lawrence he had a chip on his shoulder—not just because Lawrence had achieved, it seemed almost effortlessly, the fame that eluded Aldington himself, but also because Aldington had served through some of the worst fighting on the western front, rising from the ranks to become a commissioned officer in the Royal Sussex Regiment. Aldington had been gassed and shell-shocked, and his experience of war made him contemptuous of Lawrence’s role in what Lawrence himself described as “a sideshow of a sideshow"; he remarked disparagingly to a friend, “These potty little skirmishes and sabotage raids which Hart and Lawrence call battles are somewhat belly-aching to one who did the Somme, Vimy, Loos, etc.” Not only did it seem to Aldington that Lawrence had had an easy war of it compared with those who fought in the trenches, but Lawrence had been rewarded with fame beyond even his own imagination, with decorations and honors that he had treated contemptuously and with the friendship of great and powerful figures. In short, whether Aldington realized it or not, his book about Lawrence was spoiled by his own envy of his subject from the very beginning; and the more deeply Aldington delved into Lawrence’s life, the more bitter he became.

Aldington was one of those people who take everything literally—even his admirers do not credit him with a sense of proportion (or a sense of humor)—and the tone of his book about Lawrence was, from page 1, that of a man in a rage; it was a sustained 448-page rant, in which he at tacked everything about Lawrence, apparently determined to blow up the legend once and for all. Much of it is minor stuff; partly, this is the fault of Lowell Thomas and Lawrence’s other early biographers—his friends Robert Graves, the poet and novelist; and B. H. Liddell Hart, the military historian and theorist—who had written panegyrics to Lawrence without any serious effort at independent research or objectivity. Sooner or later, somebody was bound to come along and correct the balance.

It was Aldington’s misfortune, however, to have unearthed proof that Lawrence and his four brothers were illegitimate, and to reveal it while Lawrence’s mother was still alive. This struck most people, even those who were not admirers of Lawrence, as tactless and cruel.

Aldington was also the victim of an idйe fixe: he believed that his whole case rested on whether or not Lawrence had told the truth in saying that he had been offered the post of British high commissioner in Egypt in 1922, when Field Marshal Lord Allenby seemed about to give it up in disgust. This dispute, into which Winston Churchill, then in his last year as prime minister, was drawn most reluctantly, sputtered on for ages, though it is obvious to anybody reading about the episode today that Churchill, then colonial secretary, in fact didsuggest this appointment to Lawrence, though perhaps not altogether seriously, and that Lawrence, who never wanted the post, which was not in any case for Churchill to offer, later came to the conclusion that it had been offered to him genuinely. This was a reasonable belief, since Churchill was given to just that kind of impulsive gesture; and Lloyd George, then the prime minister, and himself notoriously impulsive about offering people high government positions without informing his colleagues in the cabinet, seems to have brought the subject up with Lawrence as well.

In any event, Aldington’s book, when it was eventually published in 1955 after years of bitter quarrels with his own publisher, his long-suffering editor, and innumerable lawyers, brought down on him a landslide of abuse and criticism on both sides of the Atlantic. He succeeded in tarnishing Lawrence’s image for a time, but at the cost of his own reputation and career—a sad object lesson in the perils of obsessive self-righteousness.

Aldington might have known better had he written a biography of Nelson instead of Wellington, for Nelson, despite character flaws that in some ways mirrored those of Lawrence, won a permanent place in the hearts of the British, while the victor of Waterloo, a cold and haughty aristocrat, never did. Nelson, like Lawrence, was a man who desperately craved attention and sought fame, who artfully cloaked vanity and ambition with humility, whose private life was something between a muddle and a disgrace, and who constantly appeared in the limelight without ever appearing to seek it. Like Lawrence he was small, physically brave to an extraordinary degree, able to endure great pain and hardship without complaint, and indifferent to food, drink, and comfort. Unlike Lawrence, he not only avidly sought honors, medals, titles, and decorations, but insisted on wearing them all even when doing so put his life at risk. However, both of them were cast from the same mold, heroes whose human weaknesses and flaws merely made them loved all the more, both by those who knew them and by those who admired them from afar. From time to time, in the more than two centuries since Nelson’s death, people have written books attempting to put his myth in perspective, but to no avail—he remains as popular as ever, and hardly a decade goes by without the launching of a biography, a film, or a novel* (for example, there was a novel by Susan Sontag), adding yet another layer to his fame. So it is with Lawrence.

The release in 1962 of David Lean’s monumental epic film Lawrence of Arabiaas good as washed away Aldington’s attempt to tarnish Lawrence’s legend. One of the longest, most beautiful, most ambitious, and most honored films ever made, Lawrence of Arabiaintroduced a new generation to Lawrence the man and Lawrence the legend, and returned Lawrence to the kind of celebrity he had enjoyed (or endured) when Lowell Thomas first brought him to the screen in 1921.

The real hero of Lawrence of Arabiais neither Lawrence nor its director, David Lean, but its producer, Sam Spiegel, who not only persuaded Columbia Pictures to finance one of the most expensive films ever made, but who put it in the hands of a director notoriously resistant to the wishes of a studio, and quite as determined as Lawrence had been to have his own way.

The genesis of Lawrence of Arabiawent back a long way, with many false starts and disappointments—enough to discourage anyone less resilient than Spiegel. When Lawrence died in 1935, Alexander Korda still owned the rights to Revolt in the Desert.He had agreed not to make a film so long as Lawrence was alive, but with Lawrence’s death he was free to proceed. He had a star in mind to play Lawrence, the English actor Leslie Howard,* who had been a big success in Korda’s The Scarlet Pimpernel; and he spent a good deal of time and money developing a script, written by Miles Malleson, who would go on to become a beloved English character actor, and edited by none other than Winston Churchill, then still in the political wilderness.

Korda’s film was never made. Financing was difficult; more important, Korda, who was always sensitive to the opinions of those in government and in “the City,” soon discovered that nobody wanted it made. A big film about Lawrence was bound to offend the Turks, who did not want to be reminded of their defeat; it would also anger the Arabs, who would not be pleased by the portrayal of the Arab Revolt as being led by a young English officer. Since it was hoped that the Turks might fight on the Allied side if there was another war, or at least stay neutral, and that the Arabs would stay quiet, it was discreetly suggested to Korda that it might be better to put the film aside for the moment. Nobody wanted to see angry Arab mobs burning down cinemas in Cairo, Damascus, Jerusalem, and Baghdad, or burning Lawrence in effigy again. Korda took the setback philosophically, and stepped neatly from one desert film to another, sending his brother Zoltan off to make The Four Feathers,a film that could offend nobody but the Sudanese, about whose feelings few people cared in those days, and that turned out to be a huge hit.

Once World War II began, the film about Lawrence went to the bottom of Korda’s large pile of optioned and purchased books; and after the war, events in the Middle East—anti-British rioting, assassinations, and the Arab-Isreali war—made the project seem even less appealing. Occasionally Korda floated rumors that he was planning to make it, now with Laurence Olivier as Lawrence, but that was only in the hope of interesting somebody who would take it off his hands. That person eventually turned up in the larger-than-life form of Sam Spiegel, a producer whose taste for the grand film was equal to Korda’s, and who bought the screen rights to Revolt in the Desertover luncheon at Anabelle’s, the chic club next door to Korda’s offices at 144-146 Piccadilly. Spiegel bought the whole package: the book, the existing screenplay, all the preliminary sketches. (Over coffee, brandy, and cigars, he also bought the film rights to The African Queen,which prompted Korda, in a rare burst of poor judgment, to say, “My dear Sam, an old man and an old woman go down an African river in an old boat—you will go bankrupt.”)

Perhaps the only person who could have brought Lawrence of Arabiato the screen was the indefatigable Spiegel, who made the impossible happen by sheer willpower and chutzpah on an epic scale. To begin with, because of the numerous Arab wars against Israel, the cause of Arab freedom and independence was not a popular one in Hollywood. Then too, Spiegel began by hiring Michael Wilson, an experienced screenwriter who had been blacklisted during the McCarthy era, to rewrite the original script—Spiegel hired blacklisted talent because it was cheaper, not out of political sympathy. Then, when Wilson’s screenplay turned out to have an antiwar tone inappropriate to Lawrence, he hired Robert Bolt, an Englishman, to make it more triumphant. His first choice for Lawrence was Marlon Brando, whom he had hired for the lead in On the Waterfront;and on this assumption he was able to persuade Columbia Pictures to finance the film, which, from the beginning, was planned as an epic that would appeal to both an American and an international audience. Spiegel managed to keep Columbia on the hook even after Brando turned down the role, as did Albert Finney, a British actor who was in any case hardly the big international star Columbia had been counting on. Finally, Spiegel got Columbia to accept Peter O’Toole, a comparative unknown, in the title role, as well as a British director, David Lean, known for his grandiose (and expensive) ideas and his determination not to be bullied by studio executives. Spiegel also hired a supporting cast of predominantly British actors, including Alec Guinness to play Feisal, and an Egyptian unknown, Omar Sharif. Nobody but Spiegel could have persuaded Columbia to finance this package, or to sit still through the interminable problems of filming on three continents, let alone to accept a film that was 227 minutes long, with a musical prelude and an intermission.