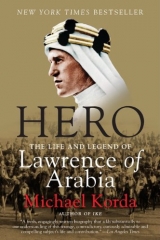

Текст книги "Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia "

Автор книги: Michael Korda

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 55 страниц)

As a sign of his regard, Allenby insisted that Lawrence should be present as part of his staff when he entered the city, so Lawrence borrowed bits and pieces of uniform from the other staff officers, and resplendent with red staff collar tabs and a major’s crown on each shoulder, he walked behind Allenby on December 11, through the Jaffa Gate and into Jerusalem.

Sykes had originally hoped to write Allenby’s proclamation to the inhabitants of Jerusalem himself, and as a new convert to Zionism he wanted to include a few rousing words about the Balfour Declaration; but after due deliberation by the cabinet, Lord Curzon was asked to draft a more cautious message, merely promising to safeguard “all institutions holy to Christians, Jews and Muslims,” and declaring martial law. Within hours after the city was taken, the pattern of the future was clear: the Ashkenazi Jews were exultant that Allenby had entered the city “on the Maccabean feast of Hanukah,” though this timing had been wholly unintentional; the Arabs complained not only about that, but about their suspicion that the Jews were attempting to “corner the market” in small change; and Picot protested that the right of the French to have their soldiers, and theirs alone, guard the Holy Sepulcher was being ignored. Lawrence wrote his first letter home in more than a month to tell his family that he had been in Jerusalem, adding that he was now “an Emir of sorts, and have to live up to the title,” and that the French government “had stuck another medal” onto him. This medal was a second Croix de Guerre, which he was trying to avoid accepting, no doubt in part because it would surely have involved being kissed on both cheeks by Picot.

Storrs, who had missed the official entry, arrived to take up his surprising new duties as “the first military governor of Jerusalem since Pontius Pilate,” with the temporary rank of lieutenant-colonel. It was in this capacity that Storrs first met Lowell Thomas, the brash American journalist, documentary filmmaker, and inventor of the travelogue. Thomas was a former gold miner, short-order cook, and newspaper reporter with a gift for gab, who had studied for a master’s degree at Princeton, where he also taught, of all things, oratory, and who had been sent by Woodrow Wilson, a former president of Princeton, to make a film that would drum up Americans’ enthusiasm for the war and for their new allies, now that the United States had joined it—an early and groundbreaking attempt at a propaganda film. Thomas, his wife, and the cameraman Harry Chase set off for Europe, but one look at the western front was enough to convince them that nothing there was likely to serve their purpose, or to convince the American public that it was a good idea to send their sons to the war. They went on to Italy, but that was not much better—Italy was locked in battle with the German and Austro-Hungarian armies in circumstances that were almost as grim as the western front, and that would be described perfectly after the war, from firsthand experience, by Ernest Hemingway in A Farewell to Arms. There, however, Thomas learned about General Sir Edmund Allenby’s campaign against the Turks in Palestine, which sounded like more promising material for a film, and particularly for an American public to whom biblical place names—Jerusalem, Gaza, Beersheba, Galilee, Bethlehem—still had more resonance than Verdun, the Somme, or Passchendaele.

Thomas, who had the American go-getter’s ability to move like lightning when his interest (or self-interest) was aroused, quickly had himself accredited as a war correspondent; and he arrived in Jerusalem, with Harry Chase, in time to film Allenby’s entrance into the city—a worldwide scoop. Sometime later, he was buying dates on Christian Street when he saw a group of Arabs approaching. His “curiosity was excited by a single Bedouin, who stood out in sharp relief from his companions. He was wearing an agal, kuffieh, and aba such as are only worn by Near Eastern Potentates. In his belt was fastened the short curved sword of a prince of Mecca, insignia worn by the descendents of the Prophet. … It was not merely his costume, nor yet the dignity with which he carried his five feet three, marking him every inch a king or perhaps a caliph in disguise … [but] this young man was as blond as a Scandinavian, in whose veins flow Viking blood and the cool traditions of fiords and sagas. … My first thought as I glanced at his face was that he might be one of the younger apostles returned to life. His expression was serene, almost saintly, in its selflessness and repose.”

Wisely, Lowell Thomas sought out Storrs (“British successor to Pontius Pilate”), and asked him, “Who is this blue-eyed, fair-haired fellow wandering around the bazaars wearing the curved sword of—?”

Storrs did not even allow Thomas to finish his question. He opened the door to an adjoining room, where, “seated at the same table where Von Falkenhayn had worked out his unsuccessful plan for defeating Allenby, was the Bedouin prince, deeply absorbed in a ponderous tome on archeology. Introducing us the governor said, ‘I want you to meet Colonel Lawrence, the Uncrowned King of Arabia.’ ”

* to be fair, this was also true of Franklin D. roosevelt, and of course vastly more true of Stalin, whose sense of humor was directed at his terrified subordinates, and was distinctly cruel and sinister in tone.

* The lowest estimate for the number of Armenians murdered by the turks in 1915 is somewhere between 1 million and 1.5 million.

* Stirling particularly admired Lawrence’s courage and toughness, and was a good judge of both. When told of the attempt on Stirling’s life, an Arab friend remarked incredulously, “Did they really think they could kill Colonel Stirling with only six shots?” ( SafetyLast, 243).

* Jemadarwas the lowest commissioned rank in the indian army, the approximate equivalent of a lieutenant.

* Known as “Jemal the Lesser” to distinguish him from Jemal Pasha.

CHAPTER EIGHT

1918: Triumph and Tragedy

“Good news: Damascus salutes you.” —T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom Two names had come to dominate Cairo,” Ronald Storrs wrote concerning the end of 1917: “Allenby, now striding like a giant up the Holy Land, and Lawrence, no longer a meteor in renown, but a fixed star.” It is worth noting that despite the failure of the attack on the bridge at Yarmuk and the incident at Deraa (about which Lawrence had told nobody except Clayton and Hogarth, both of whom seem to have received a strictly sanitized version of the story), Lawrence’s name was already being placed in conjunction with Allenby’s, as if they were partners, rather than a full general who was the commander in chief and a temporary major who was a guerrilla leader. Lowell Thomas was not the only person to recognize that Lawrence was a great story—perhaps the great story of the war in the Middle East—as well as a genuine hero in a war in which individual acts of bravery were being submerged in the public’s mind by the sheer mass of combatants. People hungered for color, for a clearly defined personality, for a hint of chivalry and panache rather than the endless casualty lists and the sheerhorror of mechanized, muddy, anonymous death on a hitherto unimaginable scale. The desire for a hero was not limited to Great Britain—in Germany it would produce at about the same time the enduring cult of Rittmeister Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen, the famous Red Baron, the handsome, daring air ace, commander of the “Flying Circus,” with his bright red Fokker Triplane and his eighty victories.

Lawrence’s cult had started long before his arrival in Jerusalem; indeed it had its beginning among a much more critical group—his fellow soldiers. His flowing robes; his apparent indifference to fatigue, pain, and danger; his ability to lead desert Bedouin; and the fact that he appeared to be fighting a war of his own devising, with no orders from anybody except Allenby—all these gave Lawrence a legendary status well before the arrival of Lowell Thomas and Harry Chase. Lawrence had already mastered the art of seeking to avoid the limelight while actually backing into it—as his friend Bernard Shaw would write, years later: “When he was in the middle of the stage, with ten limelights blazing on him, everybody pointed to him and said: ‘See! He is hiding. He hates publicity.’ ”

Storrs had unwittingly introduced Lawrence to the man who would shortly make him perhaps the world’s first media celebrity and also the media’s victim. This is not the only thing that happened in Jerusalem. Lawrence gleefully records that at an indoor picnic luncheon after Allenby’s entrance into the city, Franзois Georges-Picot announced to Allenby that he would set up a civil administration in Jerusalem, only to be fiercely snubbed by Allenby, who pointed out that the city was under military government until he himself decided otherwise. It was a bad day for Picot, who had been greeted everywhere on his way to Jerusalem (with the amiable Storrs as his traveling companion) as France’s high commissioner for Palestine, and was now reduced to the role of a mere political officer attached to the French mission. To his fury he had been placed next to Brigadier-General Clayton in the order of precedence of those following General Allenby into Jerusalem.

Even more pleasing than this snub to the French was the fact that Allenby had important plans for Lawrence in the next stage of his campaign. Given the weather and the number of casualties he had already sustained, Allenby intended to stay put for two months, and then, in February, advance north from a line drawn from Jerusalem toward Jericho and the mouth of the Jordan River. He wanted Lawrence to bring what was now being rather grandly referred to as the “Arab army” to the southernmost end of the Dead Sea, concentrating at Tafileh, both to discourage the Turks from launching an attack against the flank of the British army, and to cut off the supplies of food and ammunition that the Turks were sending the length of the Dead Sea. Lawrence agreed to this—the area was one where the tribes were friendly to Feisal—and suggested that after Allenby took Jericho, the headquarters and supply base of the “northern Arab army” be moved from Aqaba to Jericho and supplied by rail. He did not mention that this position would make it easier for the Arabs to reach Damascus before the British could get there, and he indulged in a certain amount of flimflam, which may not have fooled a man as astute as Allenby. The “northern Arab army” consisted of Jaafar’s 600 or 800 former Turkish soldiers (their number depends on whom you believe), plus however many Bedouin tribesmen could be persuaded to rally around Lawrence and Auda Abu Tayi, but its importance far outweighed its size. The most important points were that the Arab army would henceforth be acting formally as Allenby’s right wing, and that blowing up railway lines and locomotives would now take second place to advancing into Syria. Lawrence was in a position to ask for more mountain guns, camels, automatic weapons, and money. In addition, he requested, and got, the support of Joyce’s armored cars, and a fleet of Rolls-Royce tenders to support them. In his raid from Aqaba to Mudawara to attack the station there, he had remarked on how much of the desert consisted of smooth, flat, baked mud, and it seemed to him certain that a car could be driven across it at high speed, so that as the Arab forces advanced north into Syria the cars would give him vastly increased mobility and firepower.

Shortly after his return to Aqaba he and Joyce would put this to thetest by driving a Rolls-Royce tender equipped with a machine gun across the desert from Guweira to Mudawara, in some places at sixty miles an hour. The trip was so successful that they went back to Guweira; gathered up all the tenders, which carried water, gasoline, spare tires, and rations; and drove back to Mudawara to shoot up the station there, opening up a new phase in desert warfare that would be imitated in the Libyan Desert by the Long Range Desert Group from 1941 to 1943. The cars Lawrence used were not tanks, of course, and he could not use them to attack Turkish fortifications, but they helped to keep the Turks bottled up in their blockhouses and trenches, while the Bedouin rode where they pleased and destroyed stretches of undefended railway.

Lawrence’s experience at Deraa, and the fact that Turks’ price for him, dead or alive, had risen from the Ј100 they would pay for any British officer to “twenty thousand pounds alive or ten thousand dead” after the attack on the general’s train, also persuaded him to enlarge his personal bodyguard. Its members were loyal only to him, “hard riders and hard livers: men proud of themselves and without family,” as he described them, though they were often men whom other Bedouin regarded as troublemakers or worse, “generally outlaws, men guilty of crimes of violence.” Chosen from different tribes and clans so that they would never combine against Lawrence, they were ruled and disciplined with “unalloyed savagery” by their officers. Their flamboyance and their total commitment to “Aurens” raised eyebrows among both the Arabs and the British. “The British at Aqaba called them cut-throats, but they cut throats only to my order,” Lawrence would boast, and they would eventually grow to a force of ninety men, dressed “like a bed of tulips,” in every color of the rainbow except white, which was reserved for Lawrence alone, and armed with a Lewis or Hotchkiss light machine gun for every two men, in addition to each man’s rifle and dagger. This was a protective force far larger than that of any Arab prince at the time, as well as better paid, better armed, and better dressed (at the British taxpayers’ expense), and it confirmed Lawrence’s growing prestige. He also used his bodyguard as shock troops—more than sixty of the ninety would die in combat. They were recklesslyloyal to him, and referred to him as “Emir Dynamite” because of his continuing interest in blowing up trains, rails, and bridges.

Implicit in Allenby’s plans for 1918 was a fundamental change in the tactics of the Arab army from guerrilla skirmishing on the border of the desert to a full-fledged attack by the Arab “regulars” on Turkish-held towns. The Arabs would not only have to fight against Turkish troops, but take ground and hold it—something they had never done before, and that Lawrence had hitherto been determined to avoid. Lawrence saw at once that four small rural towns, which marked the border between cultivated land and the desert, represented the key to the next phase of the march toward Damascus. Maan was too far south, and too heavily garrisoned by the Turks, to interest him. But to its northwest, only a few miles from Petra, lay Shobek, with its store of wood for fueling the railway; the Arabs had taken Shobek once in October for a few days. Tafileh was next, “almost level with the south end of the Dead Sea…. Beyond it lay Kerak, and at the northern end of the Dead Sea, Madeba.” Each of these towns was about sixty miles away from the next, and they formed a chain that the “northern Arab army” might climb up until it made contact with Allenby’s army advancing on the other side of the Dead Sea to take Jericho.

A Turkish attempt to make a sortie out of Maan to protect Shobek had already been repulsed by the Arabs; one Turkish battalion, which lagged behind, had been cut to pieces by the Arabs—a taste of things to come. By January 1918 the Turks were effectively bottled up in Maan again, while the “motor-road” was completed—an astonishing feat in this part of the world—from Aqaba up through Wadi Itm to Guweira, from which the mudflats of the desert stretched out for many miles. Guweira became the advance base of operations. From it, large sections of the railway to Medina were now only an hour’s drive away. The Turks could drive off camel-mounted tribesmen, but there was no way they could defend the railway against armored cars. Lawrence was, in the words of Liddell Hart, “at least a generation ahead of the military world in perceiving the strategic implications of mechanized warfare,” andputting it into effect. Henceforth, cars and trucks began to play almost as important a role in Lawrence’s plans as camel-or horse-mounted Bedouin, and when he finally arrived in Damascus it would be in his own personal Rolls-Royce tender, which he named “Blue Mist,” seated next to a British Army Service Corps driver and surrounded by his own colorful bodyguard.

Few tasks in warfare are more difficult than combining a guerrilla army with a regular one to wage a conventional war, and doing so while continuing to fight. Lawrence hoped to take Tafileh, the most important of these towns, by tackling it “simultaneously from the east, from the south, and from the west.” To do this it would be necessary to take Shobek first, cut the railway line between Maan and Amman, and then attack Tafileh from the east, out of the desert, using a combination of mounted infantry under the command of Nuri as-Said (a future prime minister of Iraq) and whatever tribal levies could be produced by the Abu Tayi and their rivals the Beni Sakhr. The mixture of tribes, of Arabs and British gunners and drivers, not to speak of the overwhelming presence of Auda, was bound to create difficulties. Although this was desert warfare, it was winter; and on the high plateau, more than 3,000 feet above sea level, winds howled in from the Caucasus bringing snow, ice, and freezing temperatures—conditions that were underappreciated in Khartoum, Cairo, and London. Among the regular, uniformed Arab troops, many of whom had been issued only one blanket and were dressed in tropical khaki drill, it would not be uncommon for men to freeze to death during the night; and even among the Bedouin, with their thick, heavy cloaks, men would still suffer frostbite or die.

In the first week of January, Lawrence had enough to keep him busy in Aqaba, as the elements of his plan were put into motion. The Bolshevik Revolution had brought the Sykes-Picot agreement out into the open, and, predictably, it was causing doubts among the Arab leaders. It inspired Jemal Pasha to write to Feisal, proposing “an amnesty for the Arab Revolt,” and suggesting that an Arab state allied to Turkey might be more in the Arabs’ interest than an outcome in which the Allies would carveup the Turkish empire, giving the British Iraq, the French Syria and Lebanon, and the British and the Jews Palestine. Feisal forwarded this letter to Cairo, no doubt as a proof of his loyalty, but Lawrence encouraged him to reply to it, and to keep up a secret correspondence—or perhaps felt unable to prevent this. Even though Arab leaders had already guessed what it contained, the Bolsheviks’ publication of the terms of the Sykes-Picot agreement threatened to undermine such trust as had been built up between the Arabs and Britain; and Lawrence, as he was in any case bound to do, no doubt thought it better to let Feisal explore various options. It did not help much that London had finally decided to publicize the Arab Revolt. Bringing his usual white-hot enthusiasm to bear on the subject, Sykes cabled Clayton to “ring off the highbrow line” of dignified press releases about British respect for all faiths in the Holy Land. Sykes wanted a propaganda blitz that would appeal to everyone, from “English church and chapel folk” to “the New York Irish,” not to speak of “Jews throughout the world.” Sounding just like Lord Copper in Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop, he demanded local color: “Jam Catholics on the Holy Places…. Fix Orthodox on ditto…. Concentrate Jews on full details of colonies and institutes and wailing places[!] … Vox humana on this part.”

Clayton, an experienced and secretive intelligence officer, was hardly the right person to launch this flood of propaganda—on the contrary, his specialty was avoiding reporters—but gradually the British press, whipped on by Sykes, began to focus on the Middle East in the afterglow of the conquest of Jerusalem. Lawrence’s fame began to spread far beyond Cairo and the office of the chief of the imperial general staff (CIGS) in London—a fact that would have a major impact on his life less than two months later, when Lowell Thomas and Harry Chase finally arrived in Aqaba to make Lawrence once and for all the central figure in the Arab Revolt and put him and the Arabs, at last, not only on the map but, more important, on film.

Lawrence spent the early days of January composing a long and sensible report on the situation, perhaps intended to take Clayton’s mind off Feisal’s correspondence with Jemal Pasha, though its conclusions aboutSyria were such as to prevent it from being published in the Arab Bulletin; it was circulated only among senior British intelligence officials who could be trusted to keep it out of the hands of the French. Lawrence also dealt with a minor breach of discipline, albeit one that could have had serious repercussions, in a way that makes any careful reader of Seven Pillars of Wisdom realize just how tangled Lawrence’s feelings on the subject of sex and corporal punishment were.

If we bear in mind that the incident at Deraa had happened only six weeks earlier, it is surprising to read that when an Arab youth of seventeen, Ali el Alayan, an Ageyl camel man of his bodyguard, was “caught in open enjoyment of a British soldier,” by which Lawrence seems to have meant that the British soldier had been buggering the Arab or vice versa, Ali was tried in five minutes and sentenced to 100 lashes, as “appointed by the Prophet,” which Lawrence reduced to fifty. The Arab boy “was immediately trussed over a sand-heap, and beaten lustily.” Meanwhile Lawrence told the British soldier, Carson, “a very decent A.S.C.* lad,” that he would have to turn him over to his officer, who was returning to Aqaba the next day. Carson “was miserable at his position"—understandably, since in those days, and indeed through World War II and for some years beyond it, a homosexual act committed by a member of the British armed forces was both a military and a criminal offense.

When the British NCO in charge of the cars, Corporal Driver, appeared and asked Lawrence to hush the matter up for the boy’s sake before their officer returned, Lawrence refused. He was not shocked; nor did he condemn the act morally—"neither my impulses nor my convictions,” Lawrence wrote later, “were strong enough to make me a judge of conduct"—it was simply a matter of Anglo-Arab justice. It was important that there be equity, he told the British corporal. He could not “let our man go free…. We shared good and ill fortune with the Arabs, who had already punished their offender in the case.” The corporal, who was clearly experienced and reasonable, explained that Carson “was only a boy, not vicious or decadent,” and “had been a year without opportunity of sexual indulgence.” He also, though with considerable tact, laid part of the blame on Lawrence, who, for fear of venereal disease, had posted sentries to prevent British troops from visiting the three hardy Arab prostitutes who plied their trade at Aqaba.

Corporal Driver, having made his point respectfully, returned in half an hour and asked Lawrence to come and have a look at Private Carson. Lawrence, thinking Carson was ill, or had perhaps tried to harm himself in dread of the disgrace to come, hurried to the British camp, where he found the men huddled around a fire, including Carson, who was covered with a blanket, looking “drawn and ghastly.” The corporal pulled off the blanket, and Lawrence saw that Carson’s back was scored with welts. The men had decided that Carson should receive the same punishment as Ali, “even giving him sixty instead of fifty, because he was English!” They had carried out the whipping in front of an Arab witness from Lawrence’s bodyguard, “and hoped I would see they had done their best and call it enough.”

Lawrence’s reaction was odd. “I had not expected anything so drastic, and was taken aback and rather inclined to laugh,” he wrote, and noted that Carson was eventually sent “up-country,” where “he proved to be one of our best men.” Reading between the lines, we can easily guess that a wink passed between Lawrence and Corporal Driver. The Arabs not only were satisfied by Carson’s punishment but apparently assumed that Lawrence had ordered it; and certainly it was well within the old-fashioned traditions of British military discipline to keep an incident like this “within the family,” rather than let it go to a court-martial, which would disgrace the whole unit.

What is harder to understand is why Lawrence included the story in his book at all—it feels out of place, squeezed in between a long description of how he selected his bodyguard and the plans for his campaign against Talifeh. It is preceded by a puzzling disquisition on sex in Arabia, in which Lawrence remarks that “the sacredness of women in nomad Arabia forbade prostitution” (yet there were three prostitutes in Aqaba),and argues that “voluntary and affectionate” sexual relationships among Bedouin were better than “the elaborate vices of Oriental cities” or—in an odd aside—"the bestialities of their peasantry with goats and asses.”

Aside from the fact that stories about peasants having sex with their animals are common to every country and culture, it is hard to see how “the elaborate vices” of Oriental cities would be different from or worse than those practiced in the open air at Aqaba. Granted that frankness about acts and words that were still taboo was one of the things Lawrence sought to bring to literature later on, there is still something disturbing about a man who has recently endured a savage whipping himself feeling “rather inclined to laugh” at the spectacle of two young men just having been whipped. There is also an uneasy feeling of sexual ambivalence—or perhaps simply a lack of sympathy with or understanding of the sexual impulse, which seems to affect Lawrence whenever he writes about what was, for him, an uncongenial subject.

By the second week of January, Lawrence was on the move again. He rode out into the desert with his bodyguard to reconnoiter a ridge overlooking the railway station Jurf el Derawish, thirty miles north of Maan. Deciding that the position was a good one, he brought up Nuri as-Said, with 300 Arab regulars and a mountain gun. Under the cover of darkness, he cut the railway line above and below Jurf, and at dawn opened fire on the station with the mountain gun, silencing the Turkish artillery. Then the Beni Sakhr charged on camels from their position behind the ridge, where they had been hidden. The Turkish garrison, surprised and overwhelmed, surrendered when Nuri captured the Turks’ own gun and turned it on the station at point-blank range. Twenty Turks were wounded or killed, and nearly 200 were taken prisoner—but the discovery of two trains in the station loaded with delicacies for the officers in Medina set the Arabs off on a prolonged burst of looting and gorging, and as a result they missed an opportunity to destroy another train as it approached the station.

During two days of extreme cold, heavy snow, and hail, the tribesaround Shobek, near Petra, stormed and took the town. Hearing the news Nuri rode on to Tafileh through the night, and halting at the edge of the cliff above the town at dawn, he demanded that the town surrender or be shelled, even though his gun and his troops were far behind him. The Turks hesitated—they too had heard the news of the capture of Jurf and Shobek, but they were 150 men, and well armed. Then Auda Abu Tayi cantered out in full sight of them, his heavy cloak flowing behind him, and called out: “Dogs! Do you not know Auda?”

In Liddell Hart’s words, “The defences of Tafila* collapsed before his trumpeting voice as those of Jericho had once collapsed before Joshua.” Holding on to the place was harder, however, since the Arabs immediately began quarreling among themselves, and the majority of the townspeople who were Arab were divided in their loyalty to different clans. Lawrence arrived, and began to spread around gold sovereigns to induce peace, but he had hardly even begun to restore order when news reached him that a sizable Turkish force was marching from Amman to retake Tafileh, consisting of “three … battalions of infantry, a hundred cavalry, two mountain howitzers and twenty-seven machineguns … led by Hamid Fakhri Bey, the commander of the 48th Division.” By late afternoon, the Turks had brushed aside the Arab mounted pickets guarding Wadi Hesa, “a gorge of great width and depth and difficulty” ten miles north of Tafileh, which, like almost every place in Palestine and western Syria, was part of biblical geography, cutting off the land of Moab from that of Edom. Lawrence had been elated by the capture of Jurf, Shobek, and Tafileh, but he was dismayed by the swift response of the Turks; he had assumed they would be too busy defending Amman to worry about retaking Tafileh.

In ordinary circumstances, the right thing for the Arabs to do in the face of a powerful Turkish advance would have been to withdraw, first destroying whatever they could in Tafileh, and carrying away as much booty as they could load on their camels. Instead Lawrence decided to fight a conventional battle, marking a new stage in the development of theArab army. He was moved in part by the plight of the residents of Tafileh, whom the Turks would certainly punish severely for surrendering the town, and in part by a desire to prove to Allenby that the Arabs could fight and win a conventional battle.

Until now, Lawrence had been following his own maxim: “To make war upon rebellion is messy and slow, like eating soup with a knife,” and his aim was to keep the Turks trying to eat soup with a knife for as long as possible. His model was Marshal de Saxe, who had written, “I am not in favor of giving battle, especially at the outset of a war—I am even convinced that an able general can wage war his whole life without being compelled to do so.” Now, Lawrence, a convinced admirer of de Saxe, was following instead the formula of Napoleon: “There is nothing I desire so much as a great battle.” He had not changed his opinion about de Saxe, whose maxims would remain the essential basis for all guerrilla wars on into the present, but he recognized the political reality, which was that the British, and especially the French, were unlikely to take the Arabs’ claims to territory seriously until the Arabs had demonstrated an ability to hold their ground and beat the Turks in a conventional battle of positions. It was not that Lawrence’s philosophy of war had changed; it was that politics, and its by-product, public relations—Lawrence had already learned something from Lowell Thomas—required something more than blowing up bridges and looting trains if the Arabs were to get Damascus. Since Lawrence considered it his job to get them Damascus, he made up his mind to fight the Turks at Tafileh.