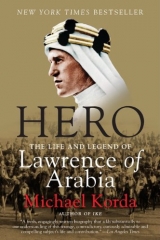

Текст книги "Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia "

Автор книги: Michael Korda

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 36 (всего у книги 55 страниц)

It is possible that the completion of Seven Pillars of Wisdommight have solved many of these problems—he had already written more than 200,000 words—but since at the time Lawrence didn’t expect to publish it, the book remained, in a sense, a perverse blind alley. One of Lawrence’s peculiarities as a writer was that despite his immense gifts, he believed firmly that writing was a skill which could be learned like demolition, and he was constantly on the lookout for people who could teach him the formula for writing poetry or constructing a sentence. More often than not, such suggestions, however sensible, were ignored. Like Charles Doughty, whose Arabia Desertahe so much admired, Lawrence seems to have invented his own prose style, which is at once archaic and lush, and becomes simple only when he is writing directly about the fighting. The descriptions of landscapes are magnificent, but throughout the whole long book—it grew to some 400,000 words at one point, and was eventually cut to about 335,000 for the so-called Oxford text of 1922, which is now regarded as definitive—there is a sense of a man perhaps trying too hard to produce a masterpiece. This need not necessarily be a bad thing—neither Ulyssesnor Finnegans Wakeis an easy book to read, after all; and D. H. Lawrence, whose books T. E. Lawrence admired (although in Lady Chatterley’s LoverD. H. Lawrence made fun of a certain “Colonel C. E. Florence … who preferred to become a private soldier”*), worked hard to produce a prose style distinctly his own. Still, there can hardly be a book in the history of English literature that was ever more thoroughly rewritten, revised, and agonized over line by line than Seven Pillars of Wisdom,and the pity of it is that it shows. It was a labor, not so much of love as of need, duty, and pride, and—more than that—another self-imposed challenge.

Whatever its merits, the first draft of the book, containing all but three of the eleven sections, much of Lawrence’s research material, and many of his photographs, was either lost or stolen from him in Reading Station late in 1919—a catastrophe that can only have added to his depression. Although the full text of Seven Pillars of Wisdomwould never be published in any conventional way in Lawrence’s lifetime (he went to enormous trouble and expense, as we shall see, to produce his own limited subscription edition, and to protect the copyright in Great Britain and the United States), Lawrence had occasionally handed the manuscript to his friends for their suggestions or corrections—at least four people seem to have read it in handwritten form. That explains why he sent or gave his only copy to Lieutenant-Colonel Alan Dawnay, who was then posted to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. Lawrence went down to get his friend’s opinion and corrections, and to go back to Oxford with the manuscript. So many versions of what then happened have been related, some of them fanciful, that it has become part of Lawrence’s legend. These include the possibility that Lawrence may have “lost” the manuscript deliberately, in other words, abandoned it; that it was stolen by an agent of the British or French secret service to ensure it would never be published; and that the incident was totally fabricated by Lawrence, presumably out of morbid vanity or to add a note of drama to the writing of the book. All these theories are unlikely—Lawrence was genuinely distraught, and Hogarth was horrified when he heard of the loss.

The truth is quite simple: Lawrence had neglected to bring a briefcase with him to carry the manuscript, so Dawnay lent him an “official” one. Such a briefcase does not resemble a bank messenger’s bag, as has been suggested, but is made of black leather, with the royal coat of arms stamped on the front flap in gold—quite an impressive-looking object. Obliged to change trains at Reading, Lawrence waited in the station cafй, and when his train was called he boarded it without picking up the briefcase, which he had placed under the table. Despite great efforts, the case was never found or returned.

It may of course be true that Lawrence had a subconscious desire to lose it, though this seems rather far-fetched; and it certainly seems odd that a thief would pick up the briefcase, examine the contents, and not think in terms of returning it for a reward—but then, we have no way of knowing whether the manuscript had Lawrence’s name and address on it. In any event, it vanished. Lawrence’s initial reaction was hysterical laughter, perhaps to avoid tears. Of course it may seem odd today to give the only copy even to so trustworthy a friend as Alan Dawnay, but in those days the only way to copy a handwritten manuscript was by photographing every page. Hence most writers either typed a copy and a “carbon” or hired a typist to do it. Oxford must have been full of such typists, given the number of theses and manuscripts being written there, but Lawrence may not have wanted to be bothered hiring one, or may have felt it was too expensive.

There seems to have been no doubt in his mind that he would start from scratch and write it all over again, and Hogarth urged on him the importance of doing just that. By this time, Lawrence seems to have been fed up with All Souls, or more likely with his mother, since he spent more of his nights at Polstead Road than at All Souls, and he accepted the offer of Sir Herbert Baker, a distinguished architect he had met, to lend him the top floor of a building Baker rented in Westminster for an office. Sitting down to reconstruct a whole book would be a grueling and daunting task for anyone, but Lawrence made it an exhausting and physically punishing marathon, perhaps because only by turning it into a physical and mental challenge could he force himself to do it at all. He wrote at an incredible pace, producing “95% of the book in thirty days,” sometimes writing thousands of words at a sitting, and eventually completing more than 400,000 words. At one point he wrote 30,000 words nonstop in twenty-two hours, possibly a world’s record. It is almost impossible to keep straight the number of parts that Lawrence wrote—he called these parts “books,” and their number varies from seven to ten. Some of the books he would revise again and again over the next six years, particularly Book VI, which describes the incident at Deraa.

Probably no part of Seven Pillars of Wisdom,even the pages about Deraa, gave Lawrence more trouble than the dedication of the work, which he went to endless pains to get right. He not only wrote it over and over again, but—unsure whether it was prose or poetry—gave it to his young friend Robert Graves, already an admired war poet, to help him turn it into blank verse, and submitted it to at least one other poet for advice. Despite changes made by Graves, it is what it is, neither fish nor fowl, at once awkward and deeply moving:

To S.A.I loved you, so I drew these tides of men into my hands and wrote my will across the sky in starsTo earn you Freedom, the seven pillared worthy house, that your eyes might be shining for meWhen we came.Death seemed my servant on the road, till we were nearand saw you waiting:When you smiled, and in sorrowful envy he outran meand took you apart:Into his quietness.Love, the way-weary, groped to your body, our brief wageours for the momentBefore earth’s soft hand explored your shape, and the blindworms grew fat upon Your substance.Men prayed me that I set our work, the inviolate house, as a memory of you.But for fit monument I shattered it, unfinished: and nowThe little things creep out to patch themselves hovels in the marred shadow Of your gift. The identity of S.A. has stirred up controversy ever since the book first appeared in print, partly because Lawrence was deliberately mysterious. It has been suggested that the dedication is to Sarah Aaronsohn, a courageous Jewish spy who committed suicide after being captured and tortured by the Turks; or to Fareedeh el Akle, Lawrence’s teacher of Arabic. Since Lawrence never met Sarah Aaronsohn, and since Fareedeh el Akle lived on to great old age denying that Lawrence had dedicated the book to her, neither theory is plausible. Lawrence himself further confused the matter by saying that S.A. represented both a person and a place; but it seems self-evident from the context that the dedication is to

Dahoum, his friend in Carchemish before the war, and that it expresses not only Lawrence’s love for Dahoum but his bitter regret that Dahoum did not live to see the victory.

The first four lines also suggest a very unusual degree of grandiloquence for Lawrence: “I drew these tides of men into my hands” and “wrote my will across the sky in stars” are an usually direct claim to Lawrence’s authorship and leadership of the Arab Revolt, in contrast to his usual practice of giving full credit to other people. If they represent his real feelings—as they may, since the dedication is evidently to Dahoum—this is one of the few places where Lawrence lets his real self and his pride show through, an unexpected moment when the hero appears without apology or disguise.

Like many great works of literature Seven Pillars of Wisdomis a product of an intense obsession, driven first by Lawrence’s need to explore and explain his own role in the Arab Revolt, and second by his need to portray the revolt as an epic, heroic struggle, full of larger-than-life figures (Auda Abu Tayi, for instance) and noble motives (those of Feisal particularly). Also as with many of the world’s great books, the author was unwilling to give it up, or stop changing and revising it. Seven Pillars of Wisdomremained a work in progress until 1927, and even today is still available in two different versions. Although Lawrence was scrupulously accurate about himself, in this book he approached the Arabs in much the same spirit as Shakespeare approached the English in Henry V,determined to make his readers see them as he did—as glorious figures, inspired by a great ideal. When parts of the story did not reflect this, he played them down as much as possible.

The top floor of Baker’s building was unheated, so Lawrence worked through the nights in a “flying suit,” believing that cold, hunger, and lack of sleep would concentrate his mind. The room had neither a kitchen nor running water, so he lived off sandwiches and mugs of tea bought at street stands, and he washed at public baths, a London institution that has pretty much vanished.

In his authorized biography, Jeremy Wilson points out, correctly, that Lawrence got a head start by incorporating into his manuscript all the reports of his actions he had written for the Arab Bulletin,and that he decided to alleviate the comparative dryness of these reports by inserting long and sometimes lyrical descriptions of the landscape. This explains the curious shifts of tone in the finished book, from reportorial to lyrical. Wilson suggests that the second version—the version Lawrence wrote under such intense, self-imposed pressure—was deliberately intended to underplay the British role in the Arab Revolt, so as to build up Feisal’s claim to Syria. When he wrote the lost first draft, in Paris and on the way to Egypt and back, Lawrence may still have had some hope that the French would relent, or that the British (and perhaps the Americans) would force them to, but by the winter of 1919-1920 he can have had no such illusion, so the second draft may have been written more as a propaganda document than the first. As Wilson puts it, “the book had now assumed a strongly political role"—though what use it would have been to the Arab cause if it was not going to be published remains unclear. In any case, from the beginning, Lawrence had tried carefully to put the spotlight on the Arabs, without in any way diminishing the enormous contribution made by British money, arms, specialists, officers, and men, and by the Royal Navy. We cannot examine the first draft of Seven Pillars of Wisdom,but in every subsequent version of the book Lawrence seems notably fair-minded toward the Indian machine gunners, the British armored car personnel and drivers, and above all Allenby and his staff, though they are overshadowed by the greater glamour of the Bedouin tribesmen. Still, the book was Lawrence’s story, and his story was among and about the Arabs.

Lawrence was awash with contradictory impulses. He wanted the book to be read by those whose judgment, experience, and suggestions for changes he respected, but not to be published and reviewed in the normal way. It was as if he hoped to protect himself against criticism, allegations that he was wrong, or arguments that he had changed the emphasis of events in the Middle East to put himself in the limelight and show the Arabs in a better light than they deserved. He toyed with the idea of publishing what he called a “boy-scout” version of the book in the United States, sharply condensed, and with all the controversial material left out. He even went so far as to start negotiations for it with F. N. Doubleday, the Anglophile American book publisher, whom he had met in London—indeed his correspondence with Frank Doubleday (whose nickname, coincidentally, was “Effendi”) should be sufficient to dispel any notions that Lawrence was indifferent to money, or had no head for business. Among the dozen or so alternative ideas he had for the book, once it was completed, he considered printing one copy only and placing it in the Library of Congress to ensure copyright, or offering one copy for a sale at a price nobody would pay, $200,000 or more. The idea of an abridged edition would eventually be realized with Revolt in the Desert,in 1927, but overall the curious history of Seven Pillars of Wisdomis one of the more tangled and complicated episodes in book publishing.

The immediate reason for the negotiations with Frank Doubleday was that Lawrence needed the money to build a house on his land in Epping and to open the private press with Vyvyan Richards. The rest of Lawrence’s ideas represent imaginative ways to protect the copyright and prevent the text from being pirated without enabling people to actually buy and read the book. Throughout his life, Lawrence did his best to prevent people from reading the unexpurgated text, either because he shrewdly grasped that nothing creates more interest than a famous book readers can’t buy, or because he disliked the whole business of publication and the reviews that accompany it. Despite a reputation for innocence and eccentricity in business matters, which he was careful to maintain, the curious thing is that in the end Lawrence by and large managed to get his own way.

Had Lawrence been willing to allow Seven Pillars of Wisdomto be published in the normal way, perhaps accompanied by a numbered deluxe edition, there is no doubt that it would have been a huge best seller, and would have made him a fortune. But money was always secondary to Lawrence, whose attitude toward the whole subject was a curious blend of his father’s and his mother’s. His father, he knew, had “lived on a large scale,” on his estate in Ireland, and although Lawrence says that his father never so much as wrote out a check, Thomas Lawrence’s correspondence shows that he not only had a sound head for business but made sensible provision for his sons. Whatever mysteries may still have surrounded Thomas Lawrence, his death must have dispelled most of them. Indeed one subject over which Lawrence revealed a certain amount of bitterness was the fact that the Chapman family did not reach out to him once he became famous, and that his fame did not persuade them to accept him as one of their own.

Lawrence should have been comparatively well off. His “gratuity” on leaving the army was apparently difficult to calculate, given the many changes in his rank, and the fact that the paperwork followed far behind his travels even to EEF headquarters in Cairo, let alone back to the War Office in London. Thus, in 1919, a puzzled War Office official, wrestling with underpayments and overpayments, came to the tentative conclusion that if Lawrence had been a temporary major and “Class X staff officer,” he was owed Ј344, minus overpayments of Ј266, which would have given him a gratuity of Ј68 on relinquishing his commission. If he had been paid as a lieutenant-colonel, the gratuity should be Ј213; if he was being paid as a lieutenant-colonel anda Class X staff officer, his gratuity should be Ј464. A further calculation by a higher authority lowers this figure to Ј334. Some of this confusion is due to the exigencies of wartime service, some to the traditional inefficiency of the Paymaster Corps, and some no doubt to Lawrence’s own lack of interest in such details. A note in the file points out, for example, that there is no record that Lawrence was ever commissioned in the first place. Lawrence himself remembered receiving a gratuity of Ј110, which seems on the low side, but in any case he had accumulated almost Ј3,000 in back pay. His scholarship from All Souls was worth about Ј200 a year, and he had a set of rooms at the college, and meals, had he cared to make use of them.

Thomas Lawrence had left Ј15,000 to be divided among his sons, with the expectation that more would be coming in, in the form of a legacy from his sister, and also provided comfortably for Sarah Lawrence. After the death of Will and Frank, this legacy would have given Lawrence Ј5,000, plus the Ј3,000 in back pay. If Lawrence had put the entire Ј8,000 away in some tidy investment, it would have been the equivalent of about $600,000 in terms of today’s purchasing power, and should have produced an income equivalent to about $20,000 a year. When added to his scholarship from All Souls, this would have given him the equivalent of about $35,000 a year today—not bad for a man with abstemious habits, no dependents, and virtually no living expenses.

Perhaps because he had overestimated how much he would receive from his father’s estate, Lawrence spent a good deal of his accumulated back pay buying land at Pole Hill for the house and printing press he intended to build there. Investing in farmland was not the wisest thing to do, since the land was primarily of interest only to Lawrence himself. As for the money his father had left him, Lawrence soon found himself in what would have been for anyone else a difficult moral position. Neither Will nor Frank had lived to inherit a share of the Ј15,000 Thomas Lawrence had left his sons, so when Lawrence discovered that Janet Laurie was in desperate need of money, he gave her the Ј3,000 that would have been Will’s share. This was apparently in accord with Will’s wishes. Lawrence later wrote that Will had left “a tangle behind” with respect to Janet, without making it clear exactly what kind of tangle it was. Lawrence should have been in a position to know, since Will had made him his executor, and it certainly seems possible that although Janet became engaged to another man after Will went to war, he may still have believed she would marry him eventually, despite Sarah’s opposition. That Sarah’s opposition survived Will’s death is at any rate clear enough—as late as 1923 Lawrence was unwilling to admit even to his friend Hogarth what he had done with the money.

It is to Lawrence’s credit that he respected Will’s wishes, despite the fact that shortly after the war Janet married Guthrie Hall-Smith, who was a war hero and then an impecunious artist. She asked Lawrence to give her away at the wedding, but after agreeing, he backed out, feeling that the difference in height between them would make him look “silly,” or, perhaps more important, concerned that word of it would get back to his mother. His generosity toward Janet thus left him with virtually no capital, and drastically reduced his income.

This did not prevent him from buying rare, hand-printed books and paintings, including one of Augustus John’s portraits of Feisal (which Jeremy Wilson estimates may have cost him Ј600, roughly the equivalent of $45,000 today). Nor did it prevent him from commissioning artists to draw and paint the portraits and illustrations for Seven Pillars of Wisdom,an extended effort that took years and cost far more than he could afford. It resulted in Lawrence’s becoming one of the most important patrons of British artists in his day, a kind of modern Maecenas, but without the requisite fortune.

He enjoyed sitting for portraits, and was constantly invited to do so. He was amused and delighted when the portrait Augustus John painted of him in his white Arab robes and camel-hair cloak was sold at auction to the duke of Westminster for Ј1,000, a record price. Lawrence called it “the wrathful portrait,” presumably because of the red cheeks John had given him, for his expression in the painting is in fact straightforward and benign.

He returned to Oxford in April with much of the book in hand, and set about cutting the text for the “boy-scout” edition he had discussed with Doubleday. He eventually put this to one side, since he was adamantly opposed to publishing the book in Britain, where it could of course be expected to sell the most copies. In any case, he was soon occupied again with events in the Middle East, which were deteriorating just as he had predicted. Since nothing had been settled in Paris, discussion of the “mandates” was moved to a new conference at San Remo, a small Italian seaside resort. In comparative obscurity, now that the Americans had made it clear that they would take on no responsibilities in the Middle East, the British and French divided the whole area even more drastically than the Sykes-Picot agreement had proposed. Apart from the vast Arabian wasteland, which was left for ibn Saud and King Hussein to dispute between themselves, the British were awarded the mandates for Palestine and Mesopotamia, and the French the mandates for Lebanon and Syria.

No provision was made for an inland, independent Arab state of any kind, although a large area had been set aside for just that purpose by Sykes and Picot. Lawrence worked hard to arouse opposition to this brutal carving up, and he had a good deal of support, in the newspapers and among politicians on both sides of the House. Lawrence, despite his claim to dislike publicity, had a positive genius for getting it. Much as he would suffer, over the next fifteen years of his life, from constant speculation and headlines in the press about him, he was as adept at running a press campaign as he had been at leading the guerrillas. He was even willing to be referred to as “Colonel Lawrence,” in order to get published. He managed to get his opinions about the Middle East into almost every newspaper, from the Timesand The Observerto The Daily Mailand The Daily Express.At one point Lawrence, in a bitter outburst, compared British rule in Mesopotamia unfavorably with Ottoman rule. At another, imitating Swift’s A Modest Proposal,he suggested that if the British were determined to kill Arabs, Mesopotamia, where “we have killed about ten thousand Arabs this summer,” was the wrong place to start, since the area was “too sparsely peopled” to maintain such an average over any long period of time. He also remarked sarcastically that fighting the Arabs would offer valuable “learning opportunities” for thousands of British troops, thus adding the War Office to the list of British bureaucracies he had offended. In both Syria and Mesopotamia local uprisings rapidly got out of control, just as he had predicted, and were put down with brutal force. By the summer of 1920 Feisal had fought and lost a pitched battle against the French army in Syria, with heavy losses to the Arabs, and had been obliged to leave the country. He had been placed forcibly, but with formal politesse,on board a special train at the orders of the French government, and dispatched to Alexandria, in Egypt, together with his entourage, consisting of an armed bodyguard of seventeen men, five motorcars, seventy-two of his followers, twenty-five women, and twenty-five horses, rather to the dismay of his British hosts, who complained that “one never knows how many meals are required for lunch or dinner.” At the same time the British found themselves attacked on all sides in Mesopotamia, and threatened with growing unrest in Egypt.

Lawrence’s views were straightforward: that responsibility for affairs in the Middle East should not be divided between the Foreign Office, the War Office, the Colonial Office, and the India Office, because such a division was a recipe for disaster; that attacking the Arabs merely for attempting to get what the British had promised them was a fatal mistake; and that keeping more than 50,000 British troops in what was now coming to be referred to as “Iraq” to hold down a country that would have been peaceful and prosperous if given a reasonable degree self-government was morally wrong and financially suicidal.

Far from being extreme, Lawrence’s was the voice of reason and common sense, and his fame added a certain weight to his advice, as did the support of people like Charles Doughty, the author of Arabia Deserta;Wilfred Scawen Blunt, the Arabian traveler and poet; George Lloyd; David Hogarth; Arnold Toynbee; Lionel Curtis; and many others. Lawrence even won over St. John Philby and Gertrude Bell, despite the fact that they supported ibn Saud rather than King Hussein and the Hashemite family in the contest for power over Arabia and the Hejaz. Indeed Lawrence made a forceful case in the newspapers against the idiocy of supporting both sides in the struggle, with the India Office financing ibn Saud and the Foreign Office King Hussein. Objections were raised in the Foreign Office, particularly by Lord Curzon, about these “calculated indiscretions” by someone who had been part of the British delegation to the Peace Conference, and might still be under some obligation to the Foreign Office, but Lawrence’s campaign in favor of Feisal and an independent Arab state seems to have struck most people as moderate, sensible, and, as Curzon clearly feared, very well-informed.

Given the fact that Lawrence was merely one person whose only resources were his pen and his name, he made amazing headway in changing the British government’s ideas about the Middle East. The idea of Lawrence as a shy or reclusive neurotic is sharply contradicted by his energetic and largely successful attempt to redefine British policy in 1920. He seems to have known, met with, and written to almost everybody of consequence, including the prime minister and the editors of the leading newspapers.* Some idea of the aura of celebrity that clung to Lawrence can be gained from the introduction to his perfectly sensible piece in The Daily Express:he is described once again, in the unmistakable, gushing prose style of Lord Copper’s Daily Beast,as the “daring,” “almost legendary” “Prince of Mecca” and “the uncrowned king of Arabia,” a “slight and boyish figure … with mind and character oozing through his eyes … and an unquestionable force of implacable authority.”

Lawrence succeeded in marshaling behind his ideas a wide variety of influential figures, enough certainly to outweigh the objections of Curzon, whom he thought of, perhaps unfairly, as his bкte noire, and the Foreign Office. That was in part because the attempt to rule Iraq as if it were an extension of India was so clearly a failure, and in part because there was no appetite in Britain for the wholesale slaughter of Iraqi civilians by British troops, or for the large amounts of money needed to police Palestine and Iraq, and to suppress the Arabs’ desire for a national identity. The British had been obliged, thanks to the Sykes-Picot agreement and Lloyd George’s impulsive bargain with Clemenceau, to let the French rule and garrison Lebanon and Syria, but they were not under any obligation to follow the French example.

Although 1920 was a difficult year for Lawrence—he had lost his manuscript and had seen his hopes for Feisal and for a fair settlement in the Middle East crushed—his achievements had been nevertheless remarkable. He had rewritten Seven Pillars of Wisdomfrom scratch, and was now revising it in painstaking detail, as well as working hard on a pet project of his: to find a publisher for Doughty’s Arabia Deserta,which had long been out of print. He wrote a long introduction to the new edition of Arabia Deserta,which would be his clearest and most eloquent description of Bedouin life and Arab culture. In addition to all this, he had widened his circle of friends, not only among artists but among writers, poets, politicians, and journalists, to a degree that was to play a very important role in his life; for just as Lawrence was a prolific writer of enormously interesting letters—his correspondence represents a vast and varied literary masterpiece in some ways even more impressive and interesting than his books—he had a particular genius for friendship. When he was a loner, as he would be for the rest of his life, his friends played much the same central emotional role in his private life that family, marriage, and children play in the lives of most people. There is a tendency to write about Lawrence as if he had been a lonely man living the secular equivalent of life in a monastery—but none of this is remotely true of the real Lawrence, whose friendships were enduring and important and cut across the lines of class and rank in a very un-English way. In none of his letters does Lawrence “talk down” to his friends in the ranks, or flaunt his superior education or heroic reputation. The tone of his letters is nearly always the same—he is highly personal, at ease, solicitous, frank about himself, and eager to hear the other person’s news. His critics have taken exception to some of his letters as inappropriate or impertinent—such as those he wrote to Air Vice-Marshal Oliver Swann on entering the RAF as a recruit—but this is to ignore the fact that at heart Lawrence was indifferent to rank, and wrote in the same easy, natural style to everyone. The list of people whom he met in 1919 and 1920 and who remained his friends for life is enormous, and includes (among many others) Augustus John, Sir William Rothenstein, Robert Graves, Lionel Curtis, Eric Kennington, and Edward Marsh. For Lawrence there was no such thing as casual friendship —allhis friendships were important to him, and all those who became his friends felt in some way permanently connected to him, whatever role he chose to play in the complicated drama of his life as Lawrence afterArabia. For in many ways, the best and most productive years of Lawrence’s life were still to come. He adamantly refused to shape himself as “Colonel Lawrence” or to allow his life to be defined only by the two years he had spent fighting in the desert.