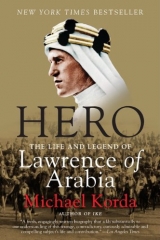

Текст книги "Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia "

Автор книги: Michael Korda

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 41 (всего у книги 55 страниц)

At the beginning of December Lawrence apparently made up his mind to publish the abridgment of Seven Pillars of Wisdom,informing Garnett that he in turn could inform Jonathan Cape of this decision, and selecting the literary agency Curtis Brown to represent him. Their task was obviously complicated by the fact that the idea of abridging the book had first been suggested to him by Frank Doubleday, the American publisher. By the first week in December Lawrence was already deep in negotiation with Cape—like so many authors, not letting the right hand know what the left one was doing, since he should have allowed Curtis Brown to do all this for him.

At this point Shaw’s immense enthusiasm for the book, which he was still reading, was clear enough, to Lawrence’s relief: “I know enough about it now to feel puzzled as to what is to be done with it,” Shaw wrote to him. “One step is clear enough. The Trustees of the British Museum have lots of sealed writings to be opened in a hundred years…. You say you have four or five copies of your magnissimum opus, At least a couple should be sealed and deposited in Bloomsbury and New York.”** Shaw was concerned about several problems of libel (given his own writing, this was a subject he was familiar with), and suggested that an abridgment, leaving out the potentially libelous passages, would be a good idea. Lawrence must have glowed at Shaw’s description of his book as a “magnissimum opus.” And he was pleased that the great man not only took the book seriously, but favored an abridgment, which, between Lawrence and Garnett, was already moving forward quickly.

Between this whirl of correspondence, his motorcycle, his photography course, and the success of his campaign to get Doughty a pension, Lawrence may not have taken notice of the fact that reporters were appearing at RAF Farnborough asking questions about him. Not surprisingly, some were from the Daily Express,but there were also some from the biggest rival of the Express,Lord Northcliffe’s Daily Mail—all the big Fleet Street dailies had spies in each other’s editorial offices. On December 16, Wing Commander Guilfoyle, for whom Lawrence had already developed a strong but possibly undeserved dislike, was already writing to Air Vice-Marshal Swann that reporters had interviewed two of his junior officers, and on learning that “Colonel Lawrence” was unknown in the officers’ mess, had started to wait outside the camp gate to waylay airmen as they came and went. “Do you think,” Guilfoyle wrote stiffly, but not unreasonably, “that all this conjecture and talk is in the best interest of discipline?” Clearly, it was not, and there was worse to come.

Lawrence, in the meantime, found himself in another dilemma, this one at least not of his own making. Filled with enthusiasm for Seven Pillars of Wisdom,and acting with his usual conviction that he knew what was best for everybody, Shaw had brought the subject of the book up with his own publisher, Constable, urging the two senior partners to go after it boldly. Never one for understatement, Shaw, as he wrote to Lawrence, told them, “Why in thunder didn’t you secure it? It’s the greatest book in the world.” Shaw urged Lawrence to open negotiations directly with Constable as soon as possible, with a view to publishing an edited version of the full text first, and an abridged version later (exactly the reverse of what Lawrence wanted to do), and he bullied the two senior partners of Constable into having a talk with Edward Garnett.

This put the fat in the fire, since Garnett had already discussed the book with Cape, whose reader he was, and discussions were already taking place between Cape and Raymond Savage, Lawrence’s literary agent at Curtis Brown. Lawrence, whose intention was to bring out the abridged text first, and who had already authorized Garnett to bring the project to Cape, had to inform Shaw that all this was going on, and Shaw was, predictably, very put out. One reason for Lawrence’s enthusiasm for the firm of Jonathan Cape was that both Cape and his partner G. Wren Howard were intensely interested in producing handsome books. Their ideas about book design, layout, and typography were less extreme than Lawrence’s, but they were more likely than Constable to produce something close to what would please him. Since Cape is now a distinguished institution in British book publishing, not unlike Knopf in New York, it will surprise those who know anything about the publishing business that Shaw thundered back with a warning that Cape and Howard were “a brace of thoroughgoing modern ruffians,” and that they probably lacked the capital to produce the book. He added, for good measure, on the subject of Lawrence’s enlistment in the RAF, that “Nelson, slightly cracked after his whack on the head in the battle of the Nile, coming home and insisting on being placed at the tiller of a canal barge, and on being treated as nobody in particular, would have embarrassed the Navy far less,” a comment that was undoubtedly correct. “You are evidently a very dangerous man,” he wrote to Lawrence, with undisguised approval; “most men who are any good are….1 wonder what I will decide to do with you.”

The truth was that Lawrence felt himself already committed to Cape, and his agent was already in discussion with Cape and Howard about the contract, so Shaw’s unexpected charge into the middle of these negotiations put Lawrence in an embarrassing position with Cape, while Shaw, of course, felt foolish at having urged his own publishers to go after a book that was already as good as sold to somebody else. Over the years, this would become a pattern in the relationship between Lawrence and Shaw, yet Shaw, after an initial outburst, always forgave the younger man. From the outset, Shaw adopted the attitude of an exasperated and indulgent parent toward a wayward, difficult child. As if to demonstrate this, Shaw not only read all 300,000-plus words of the manuscript (Shaw estimated its length at 460,000 words, but this seems excessive); he also made copious, detailed notes, suggestions, and corrections, including a “virtuoso” essay on the use of the colon, semicolon, and dash, and the proposal that Lawrence drop the first chapter of the book and start with the second, which Lawrence eventually accepted, though he sensibly ignored most of the rest.

By the time Lawrence received this letter, however, his presence at RAF Farnborough had made the front page of the Daily Expressin big headlines:

“UNCROWNED KING” AS PRIVATE SOLDIER LAWRENCE OF ARABIAFamous War Hero Becomes a PrivateSEEKING PEACE OPPORTUNITY TO WRITE A BOOK The article inside was fairly innocuous by the standards of the Express,though written in its inimitable hyperbolic style—"Colonel Lawrence, archaeologist, Fellow of All Souls, and king-maker, has lived a more romantic existence than any man of the time. Now he is a private soldier.” The next day a long and more detailed follow-up piece named him as AC2 Ross, placed him at RAF Farnborough, and gave details of his daily schedule, a sure sign that somebody had been talking to the Express’sreporter. Lawrence would afterward put the blame on the junior officers, rather than his fellow airmen, and say that one of them sold the story to the Expressfor Ј30 (more than $2,000 in contemporary terms), but this number sounds suspiciously like Judas’s thirty pieces of silver, and in any case Blumenfeld was already onto the story. To put this in perspective: by 1923 Lawrence was Britain’s most famous war hero, and a media celebrity on a scale that until then had been unimagined. It was as if Princess Diana had vanished from her home and had been discovered by the press enlisted in the ranks of the RAF as Aircraftwoman Spencer, doing drill, washing her own undies, and living in a hut with a dozen or more other airwomen. Every newspaper now, from the most serious to the most sensational, rushed to catch up with the Express,briefly turning the area outside the camp gates into a mob scene of reporters and photographers.

Trenchard and Swann were appalled, but since Trenchard did not want to show that the clamor of the press could move him, he stuck to his guns for the moment. Lawrence’s “mates” took turns fooling the photographers by hiding their faces with their caps while entering or leaving the camp; and Guilfoyle repeatedly pressed Swann to remove Lawrence, earning Lawrence’s disapproval. Despite that, Lawrence became friendly enough with the adjutant, Flight Lieutenant Findlay, who was more sympathetic to his plight than the commanding officer. Findlay noted that Lawrence was genuinely “keen” on photography, and eager to get on with his course, but was “unreasonably” resentful at having to perform menial duties and camp routine—an indication that Lawrence had not yet fully understood what life was like at the bottom of the ranks. Findlay asked him “why he had recorded ‘Nil’ on his Service papers in respect of the item ‘Previous Service,’ “ to which Lawrence replied jesuitically that John Hume Ross had no “previous service.” Much later—indeed, not until June 1958—Findlay recorded his impression of Lawrence. “Participating in the life of the Royal Air Force was only a partial solution to his problem at that time, and he appeared to be still trying to shake off something. For what it is worth, a note I made at the time reads: ‘I am convinced that some quality departed from Lawrence before he became an RAF recruit. Lawrence of Arabia had died.’ The man with whom I conversed seemed but the shadow of the Lawrence who was picked up by this whirlwind of events to become the driving force of Arab intervention in the war…. It was difficult to believe Ross was the same man. The only satisfactory explanation must be that he was suffering from some form of exhaustion, that the hypersensitive man had partially succumbed to the rough and tumble of war … that he was … for the time being at least … a personality less intense.”

This was a sympathetic but entirely incorrect reading of Lawrence’s character, though it was not out of line with what Lawrence himself professed to believe—that he was no longer “Lawrence of Arabia,” and was in the process of becoming someone else. One of his reasons for writing Seven Pillars of Wisdomhad been precisely to put that whole experience behind him once and for all. Findlay refers to Lawrence’s “assumption of mental leadership” as unsettling, as was his occasional resumption of the commanding role, which is probably what prompted Shaw to call him “a dangerous man.” Findlay, even thirty-five years after the event, underrated his man.

Lawrence often made people uneasy, as if there were two separate personalities—the meek airman and the daring colonel—contending for control within him. Beatrice Webb, the astute and redoubtable Fabian social reformer, who together with her husband Sidney was among Shaw’s closest friends, described Lawrence disapprovingly after meeting him as “an accomplished poseur with glittering eyes.” Several people felt that Lawrence was a bad influence over Shaw, rather than vice versa (the majority view). “Already by the beginning of 1923,” Michael Holroyd wrote in his magisterial four-volume biography of Shaw, “Shaw was advising Lawrence to ‘get used to the limelight,’ as he himself had done. Later he came to realize that Lawrence was one of the most paradoxically conspicuous men of the century. The function of both their public personalities was to lose an old self and discover a new. Lawrence had been illegitimate; Shaw had doubted his legitimacy. Both were the sons of dominant mothers and experienced difficulties in establishing their masculinity. The Arab Revolt, which gave Lawrence an ideal theatre of action, turned him into Luruns Bey, Prince of Damascus and most famously Lawrence of Arabia. ‘There is no end to your Protean tricks …,’ “ Shaw wrote to him. “ ‘What is your game really?’ “ This was a question Lawrence was careful not to answer, then or later.

It is revealing that Holroyd refers to Arabia as “an ideal theatre of action” for Lawrence, because Shaw himself, the supreme man of the theater of the twentieth century, seemed to believe that Lawrence’s wartime self was a role that he could drop as quickly as he had picked it up, not recognizing that with Lawrence, as with himself, the role had taken over the man. “Bernard Shaw” (he disliked the name George, which reminded him of his drunken father) was an equally brilliant role, but it was not one Shaw could take off when he went home and resume the next day for the entertainment of his admirers. Neither he nor Lawrence was an actor who could change roles every night and twice on matinee days; like it or not, Shaw had over time becomethe role he had created for himself: the unorthodox, testy, argumentative agent provocateur and gadfly of British life and conventions, an amazing presence who combined some of the attributes of Shakespeare with those of Monty Python’s Flying Circus.Only his death—in 1950 at the age of ninety-four—would release him from this role.

So it was with Lawrence. He could struggle against the role he had invented; hide in the ranks of the RAF or the army to escape from it; and attempt to sublimate it into meekness, modesty, and silence—but the powerful chin, the “glittering” bright blue eyes, and the hands, at once beautiful and very strong (as Findlay shrewdly noticed), gave him away even in the drabbest of uniforms. He was nota different man after the war, “a personality less intense,” to quote Findlay. His personality, on the contrary, was remarkably consistent. His whole life had been, in a sense, a training program for heroism on the grand scale; the war had merely provided an opportunity for Lawrence to fulfill his destiny. His intense will and his determination to have things his own way were always remarkable. He had methodically pushed himself beyond his physical limits, as a child and as a youth long before the war. He had carefully honed his strength and his courage, forced himself to a lifelong repression of his own sexuality, punished himself for every temptation toward what other men would have regarded as normal impulses. Since boyhood his life had been a triumph of repression, a deliberate, calculated assault on his own senses. He would always remain, however reluctantly, a combination of hero and genius: “a dangerous man,” indeed.

Only a day after the follow-up story in the Express,the rival Daily Mailpublished a story about Cape’s negotiations to buy the rights to Seven Pillars of Wisdom,hardly a surprising leak, given the porous nature of book publishing. This news further alarmed the Air Ministry and the secretary of state for air, Sir Samuel Hoare, who had not been enthusiastic about having Lawrence join the RAF under an assumed name in the first place, and whose reservations now were vindicated, putting Trenchard in an awkward position. As for the commanding officer and the junior officers at RAF Farnborough, they now faced the difficulties of giving orders to a celebrity who was also the author of what would surely be a best-selling and widely debated book, a literary event of the first order.

Until this point, Lawrence’s writing had not been a concern. The existence of Seven Pillars of Wisdomwas known only within the limited circle of his friends. The public knew nothing about it, or about his intention to write a book describing the RAF “from the inside.” Now both books were news, and big news at that. The heart of the problem Sir Samuel Hoare and Air Chief Marshal Trenchard faced was not just that Lawrence had made news but that he now wasnews. He no longer had to doanything to produce headlines.

Unfortunately, Hoare and Trenchard were not the only people this news story took by surprise. Lawrence’s letter to Bernard Shaw explaining that he had decided to take his book to Jonathan Cape had not arrived by the time Shaw read the story in the Mail,and he was predictably outraged and baffled. Despite this initial reaction, however, he had calmed down by the time he responded to Lawrence (enclosing the clipping from the Mail):“The cat being now let out of the bag, presumably by Jonathan Cape with your approval, I cannot wait to finish the book before giving you my opinion and giving it strong. IT MUST BE PUBLISHED IN ITS ENTIRETY UNABRIDGED ….I REPEAT THE WHOLE WORK MUST BE PUBLISHED. If Cape is not prepared to undertake that, he is not your man, whatever your engagements to him may be. If he has advanced you any money give it back to him (borrowing it from me if necessary), unless he has undertaken to proceed in the grand manner.”

Shaw had completely reversed himself on the subject of the abridgment, and now thought Seven Pillars of Wisdomshould be published complete, perhaps in several volumes. He renewed his criticism of Cape in vehement terms, and had Lawrence cared to parse his letter carefully, revealed that he still had not finished reading the book, and was relying at least in good part on Charlotte’s enthusiasm. Referring to the ten years he had spent on “the managing committee of the Society of Authors,” Shaw pointed out that “there is no bottom to the folly and business incompetence of authors or to the unscrupulousness of publishers.” As if all this were not alarming, Charlotte wrote an impassioned letter, the first of many: “How is it conceivable, imaginablethat a man who could write the Seven Pillarscan have any doubts about it? If you don’t know it is ‘a great book’ what is the use of anyone telling you so ….1 devoured the book from cover to cover….1 could not stop. I drove G.B.S. almost mad by insisting on reading him special bits when he was deep in something else. I am an old woman, old enough at any rate to be your mother…. But I have never read anything like this: I don’t believe anything really like it has been written before…. Your book must be published as a whole. Don’t you see that?”

Shaw himself wrote again a few days later, blending, as was his way, advice with abuse: “Like all heroes, and I must add, all idiots, you greatly exaggerate your power of moulding the universe to your personal convictions…. It is useless to protest that Lawrence is not your real name. That will not save you…. You masqueraded as Lawrence and didn’t keep quiet: and now Lawrence you will be to the end of your days…. Lawrence may be as great a nuisance to you sometimes as G.B.S. is to me, or as Frankenstein found the man he manufactured; but you created him, and must now put up with him as best you can.” He urged Lawrence to “get used to the limelight,” and, so far as the book was concerned, reminded him that Constable was not only “keen” on it, but had “perhaps more capital than Cape,” adding forcefully that it was a duty to publish the book unabridged.

Even before this barrage of correspondence reached Lawrence he had decided to give up on the abridgment of Seven Pillars of Wisdom,and to renege on his understanding with Cape—a decision reinforced when the chief of the air staff himself made an unprecedented visit to the camp, to warn Lawrence “that his position in the RAF was becoming untenable.” Trenchard tried to soften the blow, telling Lawrence that he was “an unusual sort of person, inevitably embarrassing to a CO,” but Lawrence disagreed, and felt that if Guilfoyle were a bigger man, he could ignore Lawrence’s “lurid past,” and treat him as an average airman. One result of all the publicity was that Lawrence tended to be treated in camp as if he were an exotic exhibit in a zoo, rather than an ordinary airman learning a trade, or so he felt.

Lawrence took Trenchard’s visit to mean that he could not publish anything so long as he remained in the RAF, and he wrote to inform Cape of this. By now he had too much at stake to risk being discharged from the RAF: friendships; work that interested him; his powerful, glittering Brough “Superior” motorcycle, the Rolls-Royce or Bentley of motorcycles, with which he had replaced the more modest Triumph, handmade, idiosyncratic, powerful, precision-engineered, and very fast; even his blue uniform, sharply altered by the camp tailor to fit tightly like that of an “old sweat” or an NCO. Lawrence, it must be remembered, at the age of thirty-four had no home of his own, no family of his own, no lover, and almost no possessions; his only abode was a borrowed attic room in London, so to an extraordinary degree the RAF had become his life. The barracks, the parade ground, and the mess were all the home he had, or expected to have. The relationship between Lawrence and the RAF was neither reasonable nor explicable to civilians like Shaw—it was a love affair, albeit one-sided. He was desperate not to give all that up, and therefore decided to forgo publishing the book in any form for the time being.

Jeremy Wilson points out that the Shaws were partly responsible for this decision. It of course was exactly the opposite of what they had hoped to achieve, but by insisting that the book should be published in full, not as an abridgment, they had increased Lawrence’s doubts on the subject. Certainly Lawrence might have wondered if his newfound friendship with the Shaws had been worth the price he had paid for it so far—but it may be too that for a man in Lawrence’s fragile state of anxiety and emotional exhaustion, the pressure from all sides was simply too much for him to take. Not only was it more advice than Lawrence could cope with, but much of it was contradictory: the Shaws were pushing him to publish the full book, Trenchard was warning him that anybook might bring about his dismissal from the air force, and on the sidelines his agent (Savage), his prospective publisher (Cape), and his editor (Garnett) all urged him to proceed at once with the abridgment. In the circumstances, it was understandable that Lawrence sought some security and peace of mind by giving up the book for the moment, but ironically, this did him no good at all. By the middle of January, Sir Samuel Hoare had reached the decision, as he later put it, that “the position, which had been extremely delicate even when it was shrouded in secrecy, became untenable when it was exposed. The only possible course was to discharge Airman Ross.” Lawrence was abruptly sent on leave, then discharged, though not without protest: it began to dawn on Lawrence that he was losing not only the chance to publish the abridged book, which would have kept him in comfort, but his place in the RAF as well.

Flight Lieutenant Findlay was given the unwelcome task of breaking the bad news to him. Lawrence went to a small country hotel at Fren-sham, near Farnborough, “well-known for its large pond and bird life.” From there, he wrote to Sir Samuel Hoare asking to be given the reason for his discharge. Trenchard replied on Hoare’s behalf with a sympathetic personal letter. “As you know, I always think it is foolish to give reasons,” Trenchard wrote, pointing out that once Lawrence was identified in the air force “as Colonel Lawrence, instead of Air Mechanic Ross,” both he and the officers “were put in a very difficult position.”

Before receiving Trenchard’s letter, Lawrence had written to his friend T. B. Marson, Trenchard’s personal assistant, asking to be given a second chance. He was still sure that he had “played up at Farnborough, and did good, rather than harm, to the fellows in the camp there with me,” but this, of course, was part of the problem. Lawrence was still playing the role, even if unconsciously, of a leader of men, and the last thing that Guilfoyle or any other commanding officer wanted was one airman acting as a role model to his fellow airmen.

Trenchard moved swiftly (and perhaps mercifully) to put an end to whatever hopes Lawrence may still have had of being readmitted to the service, offering him a commission as an armored car officer, a job where his experience with and enthusiasm for armored cars would have been an asset, but Lawrence declined. He did not want a commission, and would not accept one. He returned to his attic above Baker’s office in Barton Street, Westminster, and resumed his frugal life, to look for something to replace the RAF.

He was not short of friends to search out jobs for him. Leo Amery, now first lord of the admiralty, tried without success to find Lawrence a quiet job as a storekeeper at some remote naval station, and failing that as a lighthouse keeper, but the Sea Lords were not happy at the prospect of former Aircraftman Ross in either capacity. One job offer reached Lawrence from the newborn Irish Free State, where his experience with guerrilla warfare, demolitions, and armored cars would no doubt have come in handy. (Lawrence had met Michael Collins, the charismatic Irish revolutionary, military leader, and first president of the Irish Provisional Government, in London in 1920, and the two men seem to have admired each other—not surprisingly, since Collins’s “flying columns” resembled Lawrence’s hit-and-run tactics. By 1923, however, Collins had been murdered.) In the end Lawrence’s friend Lieutenant-Colonel Alan Dawnay, who had served with him in the desert after Aqaba, managed to persuade the adjutant-general to the forces at the War Office, General Sir Philip Chetwode, GCB, OM, GSI, KCMG, DSO, who had commanded the Desert Column of the Egyptian Expeditionary Forces and later XX (Cavalry) Corps under Allenby, to slip Lawrence into the ranks as a soldier in the Royal Tank Corps.

Chetwode was something less than an uncritical admirer of Lawrence. He was the general who had asked at a staff conference in 1918, during which it was determined that Chetwode’s corps should advance on Salt while Lawrence attacked Maan, “how his men were to distinguish friendly from hostile Arabs.” Lawrence, who was in Arab robes himself, had replied “that skirt-wearers disliked men in uniform,” producing a good deal of laughter, but not really answering Chetwode’s perfectly sensible question. As for Lawrence, he repeated the story in Seven Pillars of Wisdomin a way that could only make Chetwode look pompous or foolish to readers, though elsewhere he praised Chetwode’s professionalism. However, in 1923, Chetwode, who would rise to the rank of field marshal, had of course not read Seven Pillars of Wisdom,and he shared the admiration everyone seems to have felt for Alan Dawnay, so perhaps it was the fact that the request came from Dawnay that moved him to find a place in the army for Lawrence.

When Dawnay had asked Lawrence what he was looking for, he had replied, only half jokingly, “Mind-suicide"—that is, work involving a fixed routine and no responsibility to give orders, or to make plans. Being a lighthouse keeper might have had some appeal for Lawrence had the Sea Lords been more willing to take a risk on him, but failing that, the army seemed the quickest way to vanish back into the ranks. Unlike the RAF, the army was not fussy about its recruits, and was more accustomed to having men enlist under a false name. The Tank Corps would offer Lawrence a chance to tinker with machinery, or so he thought, and he enjoyed that. Dawnay put Lawrence’s case to General Chetwode; Chetwode “sounded out” Colonel Sir Hugh Ellis, commandant of the Tank Corps Center, and reported back to Lawrence that Ellis “sees no very great difficulty about it.” So less than two months after his discharge from the RAF, Lawrence was officially enlisted in the Royal Tank Corps for seven years, plus five years in the reserve.

Before signing up, Lawrence had to find a new name, since “Ross” had been outed. Although he told any number of people, including one of his biographers, the poet Robert Graves, that he chose the first one-syllable name he found in the Army List, the truth seems rather more complicated. He had called on the Shaws, probably to tell them of his intention to join the army, and while there he encountered a visiting clergyman who, supposing him to be a nephew of Shaw’s, remarked on how much like his uncle he looked. According to Shaw’s secretary Blanche Patch, Lawrence said at once, “A good idea! That is the name I shall take!” When he signed on in the Tank Corps he gave his name as Thomas Edward Shaw. This may or may not be true, but it seems very unlikely that Lawrence’s gratitude to and admiration for Shaw did not play some role in his choice of a name. In later years, people sometimes mistook him for Shaw’s illegitimate son, and Lawrence’s use of his surname seems to have amused Shaw himself, who would write, with his usual sharp wit, on the flyleaf of a copy of Saint Joan,“To Pte. Shaw from Public Shaw.”

Private Shaw has been criticized for not denying the rumor that he was “Public Shaw’s” son, but it seems hard to imagine how Lawrence could have announced to the world at large that the rumor was untrue. It would have caused another round of sensational front-page news stories and would also have raised a subject about which both men were sensitive. In any case, Bernard Shaw (who positively gloated over the rumor that Lawrence was his son) took a pleasure that was at once wicked and benign at the use of his name; and Lawrence, having at last found the name he wanted, never changed it again. He entered the army as 7875698 Private T. E. Shaw, “and was posted to A Company of the R.T.C. Depot at Bovington,” as of March 23, 1923.

Unlike Lawrence’s entrance into the RAF, this seems to have been a quick and simple enlistment. Lawrence may have learned the value of not“going to the top,” since General Chetwode does not seem to have bothered consulting the secretary of state for war or the CIGS about the enlistment of the hero of Aqaba.

Lawrence’s enlistment in the Royal Tank Corps (RTC) was a consequence of his misery, his sense of isolation, and his feeling of failure, after his discharge from the RAF. Like his fellow recruits at Bovington, he was there because he had failed, because he had no place to go, because he had fallen so far in his own estimation that he wanted to touch bottom: “mind suicide,” as he called it himself. Nothing about the army changed his initial reaction to it: he loathed everything from the uniform to most of his hut mates. One measure of how much he disliked it is that he made no effort to secure a job he might have enjoyed, such as engine repair, but simply drifted into being a storekeeper after his recruit training.