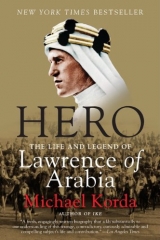

Текст книги "Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia "

Автор книги: Michael Korda

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 35 (всего у книги 55 страниц)

Thomas, who had grown up in the time of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, had a natural tendency to turn Lawrence into a figure like Billy the Kid or Wild Bill Hickok, but wearing an Arab headdress instead of a Stetson and mounted on a camel instead of a horse. Thomas was a pitchman—subtlety (like irony) was unknown to him—but still, the core of it all was the documentary film footage he and Chase shot of the Arab army advancing across the desert, its men mounted on camels and its banners flying. Audiences were fascinated by the glimpses Thomas offered of the apparently shy, slight, modest hero in a white robe—"He had a genius for backing into the limelight,” Thomas would later say of Lawrence, as their relationship cooled, and Lawrence began to feel that he was being exploited and vulgarized, and to resent the fact that he could not appear on the street without being recognized and mobbed.

Lawrence’s charisma (a concept cheapened by overuse today, but apparently only too appropriate for Lawrence) was never in doubt. In London, With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabiawould open, just as Percy Burton had promised Thomas, at the august Royal Opera House, in August 1919. It was later moved, at the suggestion of the king, to the Royal Albert Hall, which could accommodate a much larger audience, and then to the Queen’s Hall—its run in the United Kingdon alone was extended to six months, instead of the two weeks that Percy Burton had planned. Thomas also toured it in the provinces, including such cities as Birmingham, Manchester, Glasgow, and Edinburgh; and everywhere it played to packed houses. Audiences listened breathlessly as Thomas told them, for example, that he had watched while Lawrence blew up a Turkish train, and that “a number of Turkish soldiers who were about attempted to capture Lawrence, but he sat still until they were a few yards from him, then whipped out his Colt revolver, and shot six of them in turn, after which he jumped on his camel and went off across the country.” Lawrence, Thomas revealed to his audience on a lighter note, was now “in hiding, but he had received 27 offers of marriage in all.”

A command performance was held for the king; and the queen saw it twice, the second time with Princess Mary, the duchess of Albany, and the earl and countess of Athlone as her guests. At the end of the performance the queen “summoned Mr. and Mrs. Thomas … to her box … and congratulated Mr. Thomas on his eloquent descriptions and his wonderful pictorial record of the campaign.” The king of Spain saw it and “expressed himself as delighted,” and Prime Minister David Lloyd George saw it twice. Winston Churchill saw it, and sent Thomas a warm letter of congratulations on his “illustrated lecture,” as did General Sir Edmund and Lady Allenby. A handbill for the London production of what eventually came to be called With Lawrence in Arabia and Allenby in Palestineshows a photograph of Lawrence in full Arab regalia brooding over the desert, above the caption: “$250,000 REWARD! DEAD OR ALIVE! FOR THE CAPTURE OF THE MYSTERY MAN OF THE EAST.” Below that is a boldface headline: “THE MOST AMAZING REVELATION OF A PERSONALITY SINCE STANLEY FOUND LIVINGSTONE.” At the bottom of the page is a boxed quote from no less a fan than Prime Minister Lloyd George: “Everything that Mr. Lowell

Thomas tell us about Colonel Lawrence is true. In my opinion, Lawrence is one of the most remarkable and romantic figures of modern times.” Thomas, who compared Lawrence to such legendary heroes as “Achilles, Siegfried, and El Cid,” as well as to a changing list of real ones (depending on which country he was lecturing in), invented the illustrated travelogue. However, this was not a word he thought did justice to his show, which was as much a circus as a documentary—a fact that perhaps explains its enormous success.

Unaware of the approaching tidal wave of publicity, Lawrence himself had been on his way to Cairo to collect his war diaries when the Handley-Page bomber he was in crashed on landing at Rome. The pilot had committed the grievous (and elementary) error of landing withthe wind, rather than against it. Unsure whether he could stop before the end of the runway, he attempted to take off again for another try. The wing clipped a tree and the aircraft crashed, killing the pilot and copilot. Lawrence and two air force mechanics survived, though Lawrence fractured either a collarbone or a shoulder blade—the British air attachй reported first the one, then the other. He was kept in a hospital for a few days, then moved to the British embassy. The ambassador, Lord Rennell (one of whose sons would marry Nancy Mitford and appear gloriously caricatured in several of Evelyn Waugh’s novels as the scapegrace “Basil Seal”), tried but failed to keep Lawrence in Rome for a few weeks of recuperation. This attempt was, of course, a waste of time. A few days later Lawrence resumed his journey to Cairo in another Handley-Page bomber. The journey amply demonstrated the limitations of air travel in 1919, as well as the dashing, cheerful amateurishness of the infant Royal Air Force. The aircraft made emergency landings in Taranto, Valona (Albania), Athens, Crete, and Libya because of various mechanical and navigational failures. Lawrence did not reach Cairo until late in June. The crew members were awed by Lawrence’s sangfroid as they crossed the Mediterranean—a first for the Royal Air Force—and given the primitive navigational aids and undependable engines of the time, this awe was well deserved. Once they were out of sight of land, Lawrence slipped a note in the pilot’s hand: “Wouldn’t it be fun if we came down? I don’t think so!”

He managed to keep writing his manuscript even in flight—later he would claim that one chapter of Seven Pillars of Wisdomwas written while he was flying to Marseille, and that the rhythm of the prose was set by the beat of the Rolls-Royce engines. The frequent landings at primitive airfields put him out of touch with anybody who wanted to reach him, so it was not until he reached Crete that St. John Philby told him open warfare had broken out between ibn Saud and King Hussein. “Jack” Philby (who was, as noted earlier, the father of Kim Philby, the notorious Soviet double agent at the heart of MI6) played much the same role relative to ibn Saud that Lawrence played relative to Feisal, though for a longer time. Indeed Philby, who had attended Trinity College, Cambridge, with Jawaharlal Nehru and was a cousin of Field Marshal Montgomery, eventually converted to Islam and took an Arab woman as his second wife. He was also the man chiefly responsible for opening up Saudi Arabia to the American oil companies. It was a singular embarrassment to Philby that Britain was financing both sides of the war—the government of India was backing ibn Saud, while the British Foreign Office was backing Hussein. In fact the Foreign Office had been trying to reach Lawrence to ask him to mediate between Hussein and ibn Saud, but by the time he arrived in Cairo it was too late. Ibn Saud’s tribes, fanatical followers of the puritanical Wahhabi sect, had caught Hussein’s army (literally) sleeping, still in their tents, and had all but destroyed them.

Among Hussein’s mistakes was giving command of his army, such as it was, to his second son, Abdulla, a skillful diplomat but not much of a soldier. It is interesting to speculate how different the future of Arabia might have been had Feisal and Lawrence been in command of the sharifian forces—but the immediate effect was to increase the British sense of obligation toward Feisal. After all, the Hashemites would shortly become a royal family without a country or a capital, in part because the Indian government’s candidate for control of the peninsula had defeated London’s. Lawrence, when he learned about Abdulla’s defeat, did not appear to be all that surprised or upset. King Hussein had always seemed to him vain and obdurate, and Hussein had never tried hard to conceal his dislike of Lawrence; also, Abdulla had always seemed to Lawrence a reluctant, ineffective warrior. In any case Lawrence’s interest was in a modern Arab state in Syria and Lebanon, not a feudal state in the Hejaz, still less a Wahhabi state in Riyadh. Let ibn Saud rule over the vast, empty space of Arabia, so long as Feisal ruled in Damascus—this was Lawrence’s point of view. That wealth beyond any calculation lay buried beneath the sand had not yet occurred to anyone. Ibn Saud still kept the gold sovereigns he received from Delhi via Philby in an ironbound wooden chest closed with a big padlock, in his tent, guarded by one of his slaves. The notion that only twenty-six years later President Franklin D. Roosevelt would interrupt his journey home from Yalta solely to pay his respects to ibn Saud would have seemed far-fetched in 1919.

By the time Lawrence returned to Paris, the Inter-Allied Commission of Inquiry on Syria had already fizzled out. The French refused to join it, and announced in advance that they would pay no attention to its recommendations. In deference to the French, the British refused to join it, and as a consequence it consisted only of two Americans: Dr. H. C. King, a theologian and the president of Oberlin College; and C. R. Crane, “a prominent Democratic Party contributor.” Neither of them was particularly well suited to decide the fate of Syria. King and Crane spent ten hot, weary days in Damascus, and came to the conclusion that the Arabs “were not ready” for independence, but that French or British colonial rule would be morally unjust. On their return to Paris they recommended that the United States occupy Syria and guide it toward independence and democracy. By that time nobody was listening, least of all President Wilson.

Since there was nothing for Lawrence to do in Paris except go through the files of the British delegation reading unflattering comments about himself, toward the end of the summer he returned to Oxford, where his old mentor David Hogarth, and Geoffrey Dawson, the editor of the Times,had arranged a research fellowship for him at All Souls College. This entitled him to a set of rooms and Ј200 a year while he worked on his book and returned to work on “the antiquities and ethnology, and the history (ancient and modern) of the Near East.” All Souls, a college that has no undergraduates, was and remains a kind of worldly sanctuary for Oxonians who have retired from public life to pursue their studies or write their memoirs. Election to a fellowship of the college is considered a great honor. With his usual efficiency and command of the Oxford establishment, Hogarth had provided Lawrence with a way to get on with his life and write his book.

In the meantime, the Foreign Office and the War Office disputed over which of them was responsible for Lawrence, and whether he was now a Foreign Office official dressed in the uniform of a lieutenant-colonel, or a lieutenant-colonel temporarily assigned to the Foreign Office as part of the British delegation to the Peace Conference, or possibly only an adviser to Prince Feisal. He was blamed by many for “our troubles with the French over Syria,” and one official, Sir Arthur Hirtzel, at the India Office, expressed the vehement hope “that Lawrence will never be employed in the Middle East again in any capacity.” Correspondence about whether Lawrence had been or should be “demobilized” went back and forth. An exasperated officer in the Department of Military Intelligence in Paris cabled to the War Office, “Colonel Lawrence has no Military status in Paris he is however a member of British delegation under foreign office [sic] section it is also believed he is a plenipotentiary from King of Hedjaz but has not yet presented his credentials his status in Army not known here but he continues to wear uniform with badges of rank varying from full Colonel to Major.” A handwritten note on yet another attempt to clear up the matter reads: “I have tried again and again to get the F.O. to say whether Col. Lawrence is their man or not,” and bounces the question on to Allenby. Finally, an abrupt letter from Egypt addressed to Major T. E. Lawrence, CB, DSO, clears the matter up once and for all: “I am directed to inform you that having ceased to be employed on the 31st July 1919, you will relinquish your commission and be granted the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, a notification of which will appear in an early gazette.” Much correspondence and many handwritten calculations ensue in Lawrence’s army file about the size of his “gratuity” on being demobilized, which seems to work out at Ј213. Some of the correspondence is marked “Submit to King,” which suggests that King George V was not so offended by Lawrence’s refusal to accept his decorations that he was indifferent to the way Lawrence was treated on being demobilized. As for Lawrence, it is uncertain to what degree he cared or even knew—he was in the habit of tearing up, returning, or ignoring letters addressed to him with his rank and decorations.

Lawrence, thanks to his friendship with Geoffrey Dawson, was able to get his point of view printed frequently in the Times,to the embarrassment of the Foreign Office and the anger of the French. Lawrence argued that the Sykes-Picot agreement needed to be revised in the light of present realities, that this revision should be done with the inclusion of the Arabs, and that the various pledges the British government had made to the Arabs should be spelled out in detail. In the meantime, Syria continued to be occupied by British troops; this gave the British government some leverage over the situation, since what the French wanted was to replace them with a French occupation force as soon as possible. Moreover, the French wanted it done with appropriate ceremony, in order to impress on the Syrians the fact that their well-being now depended on France. The Union Jack must be pulled down in Damascus and Beirut, with “God Save the King” played for the last time, with pipers, and with all the panoply of British military ceremony, followed by the raising of the French flag and the playing of the “Marseillaise.” To this, after much correspondence, Lloyd George eventually agreed, and by the end of the year, France would be firmly in control of Lebanon, and rather less firmly in control of Syria. Feisal, who, on Lawrence’s recommendation, had stayed in Damascus rather than returning to Paris to endure further humiliation at the hands of the French,* now journeyed to Britain, where he was told that he should make the best deal he could with France, and that the British government could take no further responsibility for events in Syria and Lebanon.

Feisal does not appear to have met with Lawrence while they were both in Britain, and Lawrence’s letter to Curzon offering to “use his influence with Feisal” was ignored.

*Wigram eventually became the first baron Wigram, GCB, GCVo, CSi, PC, private secretary to the sovereign from 1931 to 1936.

*Later the rt. hon. the Viscount Cecil of Chelwood, Ch, PC, QC.

* She was then married to Sir Oswald Mosley, Bt., still a rising young politician and not yet the founder and leader of the British Union of Fascists.

*Lawrence had what appears to have been a streak of what the French call l’esprit delescalier, that is coming up with the clever last word too late, when one is already on the staircase after having left the room, and then incorporating it into later accounts of the conversation

*it would include a remarkable number of intellectually brilliant figures, from President Wilson’s powerful adviser and eminence grise Colonel edward house to such future foreign policy heavyweights as John Foster Dulles and Walter Lippmann

*Although Lawrence’s plan may have been overgenerous to hussein and his sons, it nevertheless recognized the difference between northern and southern Mesopotamia,and would have resulted in an independent Kurdish state and solved at least one of the fundamental divisive issues that plague modern iraq.

*readers may find an echo of the kind of thinking expressed by members of the committee in scene iV of G. B. Shaw’s Saint Joan, in which the (english) chaplain exclaims to the (French) bishop of Beauvais, how can what an englishman believes be heresy? it is a contradiction in terms

*This is remarkable, since King George V, like his father, was a notorious stickler for correct dress, both military and civilian, and had an eagle eye for the slightest impropriety or flaw, as well as a very short fuse in this regard.

* This is certainly a slip of Lawrence’s fountain pen, since Feisal’s memorandum to Balfour was written on January 1.

*Lawrence was not the only one to float this idea with Wilson; another was Dr. howard S. Bliss, president of the Syrian Protestant College (later the American University of Beirut). But it was shrewd of Lawrence to suggest a plan that would appeal to the democratic ideals of Wilson and would be sure to infuriate the French and alarm the British. if the Syrians, after all, why not next the egyptians, or the inhabitants of Mesopotamia,or worse yet, from the British point of view the indians?

*The United States ambassador in Constantinople was henry J. Morgenthau, Franklin Delano roosevelt’s neighbor in hyde Park, New York, and eventually his secretary of the treasury. Morgenthau reported the massacres in full detail to the State Department, as well as the matter of fact admission of the turkish leaders that the liquidation of the Armenians was taking place

*For reasons best known to themselves the French regarded the late Major General Charles Gordon, CB, “Gordon Pasha,” who was killed by the Dervishes at Khartoum in 1885, as the ultimate anti French British imperialist hero adventurer

*Demand was so great that Lowell Thomas was forced to hire an “understudy” to give some of the lectures in his place. he chose for the job a gifted young speaker named Dale Carnegie, who would himself go on to world fame and fortune as the author of How to Win Friends and Influence People, and founder of the Dale Carnegie instit

*This may not have been the best advice. Feisal might have done better to return to Paris and negotiate with the French, rather than stay in Damascus, where he came more and more under the influence of Syrian nationalist hotheads preaching resistance to France

CHAPTER TEN

“Backing into the Limelight”: 1920-1922

Any soldier’s return home after a long war is bound to be traumatic, and Lawrence’s was no exception. It was perhaps no accident, but more in the nature of a Freudian slip, that his last major written work would be a translation of the Odyssey.Neither he nor Hogarth could have believed that he would settle cozily into life at All Souls, dining at the “high table” in evening dress and black academic gown, chatting with dons and other fellows in the Common Room over a glass of port, and pursuing the research he had dropped in 1914, on the antiquities of the Near East. Hogarth could slip seamlessly back into the life of a scholar, but Lawrence’s war years had been too tumultuous for that, and his devotion to scholarship, or at any rate to the academic life, had been only skin deep to begin with. The war had not taken him away unwillingly from what he loved, but instead offered him a much more intense and dramatic life, as well as a chance to play a significant role in grand events. He was not going back to a desk at the Ashmolean Museum, with a sigh of relief, to study potsherds, and as for archaeological research in the field, neither the British nor the French government would tolerate the presence of “Colonel Lawrence,” a magnet for Arab nationalism and discontent, digging among the ruins of Carchemish, or anywhere else in the Middle East.

All Souls was a refuge of sorts from the outside world, but it was no great distance from there to Polstead Road, where Lawrence’s mother continued to try to dominate his life. For five years Lawrence had been spared his mother’s intense interest and, as he saw it, her unreasonable emotional demands, as well as the hothouse atmosphere of life in the Lawrence household. Sarah Lawrence had not only very high and unforgiving standards of behavior, but an elephant’s memory for slights, or occasions when her will had been flouted. It would be easy to suppose that Lawrence exaggerated his mother’s controlling personality, but those of his friends who met her, including Charlotte Shaw and Lady Astor—the former married to one of the more difficult personalities of late nineteenth-century and mid-twentieth-century Britain, and the latter no shrinking violet herself—seem to have been terrified of this tiny, and by then elderly, woman. Evidently, Sarah Lawrence always said exactlywhat was on her mind, without any attempt to sugarcoat it. By the early autumn of 1919 she had accumulated enough tragedy in her life to expect some emotional support from her second son, who was, of course, either unwilling or unable to provide it. Polstead Road cannot have been a place Lawrence wanted to visit, but now he was only a few minutes’ bicycle ride away, and without the tempering influence of his father.

Without Thomas Lawrence present, his widow was free to explore many of the animosities and old complaints that Ned had been spared over the years. An example was her fierce quarrel with Janet Laurie, who had fallen in love with Ned’s taller and more handsome brother Will. When the war broke out, it seems that Will, who clearly intended to marry Janet despite his mother’s opposition, wrote to ask Janet if she thought he should come home and join up, and she, after much hesitation, wrote back and told him that “it might trouble him later if he did not.” This was true, given Will’s honorable nature, but once he had been listed as missing, and then declared dead, his mother either heard about or read Janet’s letter (more likely, the latter), and blamed Janet for his death. There was a terrible “row,” and the two women did not speak again until 1932. To do Sarah justice, as a devout Christian she finally sought Janet’s forgiveness, and received it, but in 1919 Sarah’s bitterness over Will’s death was still raw.

Hearing in detail about such issues was exactly why Lawrence had left home in the first place. He was the least judgmental of men, and besides, he was still fond of Janet and would have been reluctant to take his mother’s side or even to hear it. Also, his own attitude toward the death of two of his younger brothers was modeled on Roman fortitude. When Frank was killed, Lawrence had written to his mother urging her to “bear a brave face to the world about Frank….[His] last letter is a very fine one & leaves no regret behind it….1 didn’t say good-bye to Frank because he would rather I didn’t, & I knew there was little chance of seeing him again; in which case we were better without a parting.” This was stoic, but not exactly sympathetic or consoling. Lawrence would doubtless have felt the same about Will.

Lawrence’s depression may be gauged by his mother’s recollection that he sometimes sat for hours at home, staring into space; he did the same at All Souls, to the consternation of the other fellows. At times he broke out of his depression to play undergraduate pranks, or so the poet Robert Graves, a returning officer turned undergraduate, remembered. According to Graves, Lawrence climbed a tower at All Souls to hang the Hejaz flag from its peak, kidnapped a deer from the Magdalen College deer park, and rang the station bell he had captured from Tell Shahm from his window at night. These incidents would not have been out of the ordinary for an undergraduate, but Lawrence was at the time a thirty-one-year-old retired officer, and All Souls was not a place that looked with fond amusement on high jinks by its fellows. The pranks may be seen, not so much as cheerful rebellion against authority, but more likely as an attempt to revert to the happier, easier undergraduate state of mind that Lawrence had known at Oxford from 1907 to 1910. But that world had vanished forever. Oxford in 1919 was a place where the undergraduates were for the most part ex-officers, many of them old before their time. In every college dons were busy putting up a plaque with a long list of those who had been killed from 1914 to 1918. It was as if a whole generation had simply disappeared. Lawrence did not fit in at All Souls any more easily than he did at home.

He was still working on his manuscript, but without any conviction that it should ever be published. It was a giant, self-imposed task; and whereas most people write in the expectation of seeing their books published and reviewed, Lawrence seemed to be writing to get the war, and his role in it, out of his system. Perhaps for that reason, he included material that might be judged libelous or even obscene, by the strict standards of the time.

On August 14, 1919, Lowell Thomas’s “illustrated travelogue” opened at least at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden. Lawrence had not been affected by Thomas’s success in New York—in the days before radio or television, let alone instant telephone communication, New York was far away, and a theatrical success there was merely a curiosity on the opposite side of the Atlantic. But in London Thomas made Lawrence, overnight, by far the most famous and acclaimed British hero of World War I, and what is more, a livehero, who lived only a short train ride from London. Lawrence had cooperated willingly with Thomas and Chase at Aqaba, on what he thought was a “propaganda film” for the American government, made under the orders of Colonel House, President Wilson’s closest adviser. Even so, he gave the two Americans only a few days of his time, and was notably reticent. He saw no harm in pulling Thomas’s leg, or in having a little fun at his expense, and cannot have imagined that the film would ever be made, or indeed that he would live to watch it, still less that it would be enlarged into a kind of three-ring circus. His colleagues at Aqaba had had their fun with Thomas too, telling him tall tales and burnishing Lawrence’s legend. Aqaba was a dull, infernally hot place, and the opportunity of amusing themselves at the expense of two earnest Americans was not to be missed.

None of this is to suggest that Lowell Thomas was taken in—he was anything but credulous—but he was a showman,looking for a great story and, if possible, for a British hero who could be made appealing to an American audience (not an easy task, given the constraints of the British class system). He saw no profit in skepticism, and never hesitated to turn a good story into a better one, and Lawrence was first and foremost a good story, set against a great background. Thomas made the most of it.

Although Lawrence has been criticized for cooperating with Thomas, he could hardly have foreseen that a documentary film would fill London’s biggest halls and theaters to capacity six nights a week and two matinees, let alone that the Metropolitan Police would have to be called out in force night after night to handle the huge crowds. On the night the Allenbys attended the show, Lowell Thomas reported that “Bow Street was jammed all the way from the Strand to Covent Garden … and we turned away more than ten thousand people.” Lowell Thomas’s wife, Fran, wrote to her parents that the show was having “a colossal success,” and she was not exaggerating. Lawrence himself saw it five or seven times (depending on whose account we believe), apparently without being recognized except by Fran Thomas, who noted that “he would blush crimson, laugh in confusion, and hurry away with a stammered word of apology.” That Lawrence was not initially offended at being turned into what he called “a matinйe idol” seems clear enough. He wrote a nice letter to Thomas, adding that he thanked God the lights were out when he saw the show, and invited the Thomases to Oxford for a sightseeing tour.

Thomas had not only put Arabia on the map but made T. E. Lawrence a perennial celebrity. The normally staid Daily Telegraphsummed it up nicely: “Thomas Lawrence, the archaeologist, … went out to Arabia and, practically unaided, raised for the first time almost since history began a great homogeneous Arab army.” The Telegraphpredicted that, thanks to Thomas, “the name Lawrence will go down to remotest posterity besides the names of half a dozen men who dominate history.”

Lawrence would have had to be superhuman not to feel a glow at all this fame and praise. However much he pointed out that he had notbeen unaided, that he was only one of a number of British officers helping the Arabs, his modesty only increased his popularity and fame. Here was no boastful hero, but a shy, modest, unassuming one, willing, even eager, to give credit to others. Lowell Thomas, in fact, stated how difficult it was to interview Lawrence about his own feats, then went on to publish in Strand Magazinea series of hero-worshipping articles about Lawrence, which, together with his lecture, he would soon transform into an internationally best-selling book.

“In the history of the world (cheap edition),” Lawrence complained to his old friend Newcombe about Lowell Thomas, “I’m a sublimated Aladdin, the thousand and second Knight, a Strand-Magazine strummer.”

It is against this background that one must view Lawrence’s life in 1919: as an ex-soldier struggling with a huge and difficult book; as a diplomat whose effort to give Feisal and the Arabs an independent state had failed; as a man who, to quote Kipling, “had walked with kings, nor lost the common touch,” and was now stranded in his rooms in an Oxford college, or at home under the thumb of a demanding mother, all the time besieged by admirers, well-wishers, celebrity hunters, and cranks.

Lawrence tried to take up some of his old interests—he wrote to his friend Vyvyan Richards about resuming their old plan for setting up a printing press together to produce fine, limited editions of great books. It says much for Richards’s affection for Lawrence that he was still open to this pipe dream after an interval of so many years; and it is hard not to believe that at this point Lawrence was simply casting around for some escape from the demands of his book, which was constantly growing in complexity, and from the rapidity with which his real accomplishments were being overshadowed by Thomas’s romantic image.