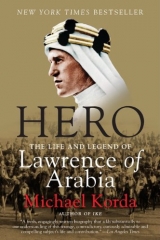

Текст книги "Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia "

Автор книги: Michael Korda

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 44 (всего у книги 55 страниц)

Lawrence was posted to B Flight, as an aircraft hand. His immediate world consisted of a sergeant, a corporal, and fourteen airmen, who shared the same hut. Their job was to look after the six training aircraft used by the fifteen officers and cadets of B Flight. The work interested Lawrence, who loved machinery, and except for an early morning parade he spent most of his day in overalls working around the aircraft. Inevitably, there was a close relationship between the pilots and their ground crew—a pilot’s life depended on the men who serviced his aircraft, so there was none of the distance that existed between officers and men in the army. Nor was any great secret made of the fact that AC2 Shaw was in fact Lawrence of Arabia. A good many of the airmen knew or guessed it, and Biffy Borton and his wife occasionally invited AC2 Shaw to their quarters for the evening, as did Borton’s chief staff officer, Wing Commander Sydney Smith, and his lively and beautiful wife, Clare. The Smiths had known Lawrence in Cairo, and both of them liked and understood him. Clare shared Lawrence’s passionate interest in music, and was able to maintain an easy and unforced relationship with him, in which neither his present rank nor his past glory was an issue. She may have been the only woman who actually flirted with Lawrence, an experience which he seems to have enjoyed.**

As for Lawrence, he himself was discreet, and never took advantage of his friendship with the Bortons and the Smiths, or with the college medical officer, an elderly wing commander who was a former surgeon to the king, and now quietly took on Lawrence as, in effect, a private patient. Normally, an airman who makes friends with officers is distrusted by other airmen, but Lawrence never lorded it over his mates or sought special favors. His own sergeant, Flight Sergeant Pugh, summed up his feelings about AC2 Shaw in words rarely heard from an NCO about any of his men: “He was hero-worshipped by all the flight for his never failing, cheery disposition, ability to get all he could for their benefit, never complaining…. Quarrels ceased and the flight had to pull together for the sheer joy of remaining in his company and being with him for his companionship, help, habits, fun and teaching one and all to play straight.” Something of his old spirit, which he had shown when teasing Auda Abu Tayi, seems to have returned, touching the men who slept in Hut 105 at Cranwell.

Of course a service college is not an ordinary camp, even for the lowliest airman. At Cranwell the focus was on the cadets, not the airmen who looked after their aircraft—and it boasted amenities that included an excellent library (to which Lawrence would add a specially bound copy of the subscribers’ edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom),a weatherproof hut for his latest Brough “Superior” motorcycle, a noncommissioned aristocracy of sergeant pilots and sergeant technicians, and even a swimming pool. Lawrence and some of his mates would run to the pool “at first dawn” on summer mornings, “to dive into the elastic water which fits our bodies as closely as a skin:—and we belong to that too. Everywhere a relationship: no loneliness any more.”

“No loneliness any more,” expresses very precisely what Lawrence sought and found in the RAF; and while the bond between Lawrence and his air force mates was hard for friends like the Hardys, the Shaws, Winston Churchill, Hogarth, and Lionel Curtis to understand, it was vital to him. He was like the kind of schoolboy who goes home on a holiday from boarding school reluctantly, because his closest friends are his schoolmates. Lawrence corresponded with his mates when he was away, sending long, interesting letters, full of what he was doing; he even corresponded with some of the soldiers he had liked at Bovington, such as Corporal Dixon and Posh Palmer, and with those airmen who had been with him in Uxbridge. He made them small loans and did them small favors, and remained genuinely interested in their lives and open about his own life.

However widespread his friendships among the rich, the famous, the talented, and the politically powerful were, it was in the barracks, not the drawing room, that he found an antidote to his loneliness.

This is not to say that Lawrence could not switch from one world to the other. He would ride his Brough motorcycle (he had christened the first one Boanerges, “Sons of Thunder,” and would continue naming the others Boanerges II, Boanarges III, etc.) down to London, or off to country houses when he could get leave, always turning up in the uniform of an airman, to the astonishment of butlers and hall porters. He paid a visit to Feisal, now king of Iraq, in London, and they both went off for lunch at Lord Winterton’s house in Surrey. Winterton, now undersecretary of state for India, had served with Lawrence in the advance on Damascus, but Lawrence tried to resist being drawn into nostalgic talk about the war. He “found Feisal lively, happy to see me, friendly, curious,” as well he might be at the sight of “Aurens” in a simple airman’s uniform—as much of a disguise, of course, as the Arab robes and headdress had ever been. Even in Lawrence’s letter to Charlotte Shaw describing this visit, his ferocious self-renunciation is replayed with frightening intensity: “So long as there is breath in my body my strength will be exerted to keep my soul in prison, since nowhere else can it exist in safety. The terror of being run away with, in the liberty of power, lies at the back of these many renunciations of my later life. I am afraid of myself. Is this madness?”

Lawrence takes delivery of a Brough Superior Motorcycle. George Brough is on the left.

Seldom has anybody stated more clearly his determination never again to be placed in a position of power over others. With all his formidable willpower Lawrence was determined to shackle the part of himself that had sought fame, glory, and greatness, and never allow it to rise again except in the pages of his book. Nobody knew better than Lawrence what he was capable of. He had executed a man in cold blood, suffered torture, killed people he loved, witnessed the ruthless murder of prisoners in the aftermath of battle. Nor was anybody more anxious to do penance. It was as if one of the great heroes of medieval times, one of those figures whose castles and tombs Lawrence had spent so much of his boyhood studying, had put aside his honors and retired in midlife to a monastery, tending to his herb garden and performing his humble chores, a simple brother, hoping not to evoke curiosity, pity, or interest. Yet, with the contradictory impulse that was so much a part of his nature, Lawrence was hard at work on two projects that were bound to stir up renewed interest in him: the completion of the thirty-guinea subscribers’ edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom(now planned to consist of 150 copies) and the abridged, popular version of the book, to be called Revolt in the Desert.Also, he had allowed Robert Graves, who desperately needed money, to convert a proposed children’s book about him into a full-scale biography.

Sometimes stormy, sometimes mundane, Lawrence’s correspondence with Charlotte Shaw continued, while she and G.B.S. involved themselves in the formidable task of proofreading the subscribers’ edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom,which Manning Pike was struggling to set as Lawrence (and the Shaws) wanted it. Some hint of how demanding the job was can be gleaned from Lawrence’s instructions to Charlotte about making insertions in the text.

This bundle of proofs is sent, with an envelope, on its way to Pike. You were not satisfied with galley 18: so I have had it re-set, or its middle part, and the new piece is pinned on…. The rules are simple:i. Page always thirty-seven lines.ii. Each page begins with a new paragraph, and a small capital extending over three lines. Spaces for these are left in the new proof.iii. The last line of each page is solid, i.e. extends to the right hand margin.iv. No word is divided.v. Paragraphs end always after the half-way across the line. Even in our own age of computerized typesetting, any one of these rules would present problems, particularly iii and iv, so it is hardly surprising that the work absorbed a huge amount of time and effort on the part of Lawrence and Charlotte and nearly drove Manning Pike crazy. It does not seem to have occurred to Lawrence that the completion of either of these two projects would bring the national press back to the gates of Cranwell in pursuit of the “uncrowned king of Arabia.” But then, with Lawrence, one never knows. He does not seem to have been able to go for more than a year or two without bringing down on his head exactly the kind of attention he claimed to fear most. As Charlotte had once told her husband, “Something extraordinary always happens to that man.”

Perhaps to alleviate Lawrence’s depression, Charlotte kept up a stream of presents. Hardly any airman at Cranwell can ever have received more frequent packages: a novel by Joseph Conrad; a bundle of magazines, followed a few weeks later by two more books, and a few days later by more magazines, newspapers, and a copy of Liam O’Flaherty’s The Informer;a week later, another novel; and shortly afterward a box of four books from an antiquarian bookseller and a gift basket of chocolates and cakes from Gunter’s, the fashionable Mayfair tea shop. The gift basket from Gunter’s arrived without a card, but Lawrence was in no doubt about who had sent it. This was a mutual though sexless seduction. Lawrence responded with long letters, sometimes gently teasing (a contrast to Bernard Shaw’s cruel teasing), sometimes self-mocking (as when Lawrence likened the sumptuously illustrated and bound subscribers’ edition to “a scrofulous peacock”); he also sent her further proofs from Pike, to be read over for misprints. Since poor Charlotte had weak eyes, her constant attention to the proofs of Seven Pillars of Wisdomis a further demonstration of her devotion to Lawrence, and his growing dependence on her. It would not be exaggerating to say that she mothered Lawrence—this was easier to do now that his mother and his eldest brother, Bob, had left to take up their own adventure as missionaries in China. For his part, he accepted being mothered by Charlotte, but there was more to it than this: they were also kindred souls, who could share with each other emotions and experiences that they could not have shared with anyone else—his reaction to the rape at Deraa, her fear of sex and childbirth—and that in Charlotte’s case would have been brushed off or explained to her in Fabian or Freudian terms by her husband. It was as close to a love affair as either of them—two people who scrupulously avoided even the mildest terms of endearment in their thirteen years of correspondence—could ever have approached.

Like so many of Lawrence’s friends, the Shaws learned to accept his appearance at their doorstep on his motorcycle, much as they disliked the machine. Lawrence had already survived two serious accidents while he was at Bovington, either one of which could easily have killed him. As the saying goes, “There is no such thing as a minor motorcycle accident.” It was not so much that Lawrence was a bad or dangerous rider—George Brough, the designer and manufacturer of his motorcycles, would argue that on the contrary, he was a skillful and careful one—but he used his motorcycle as everyday transportation, often over long distances and poor roads in bad weather. Fallen leaves, puddles, and patches of ice can all cause a skid even at less than daredevil speeds; and in the 1920s and 1930s a motorcycle headlight was, by modern standards, dim and unreliable. (It was not for nothing that Joseph Lucas, founder of the major British manufacturer of automotive electrical equipment, was known to owners of motorcycles as the “prince of darkness.”) Moreover, though Brough was something of a genius, his motorcycles were, for their day, large, heavy, and very powerful machines, a lot to handle for a slight man in his late thirties with a history of broken bones.

At an earlier stage of his life, Lawrence had traveled to far-off foreign places and had written to his family at home. Now, it was Lawrence who was in England while his mother and Bob were far away in China, which was impoverished, turbulent, dangerous, swept by competing warlords and by revolution, and at every level of society deeply hostile to European missionaries. It was now Lawrence who arranged for parcels to be sent abroad. He went to W. H. Smith’s, the British chain of newsagents, where his uniform was greeted with suspicion, to take out subscriptions to the Timesand the New Statesmanto be sent to his mother in China; he also mailed packages containing items she had requested: Scott’s journals, salts of lemon, and padlocks for her trunks. Lawrence’s youngest brother, Arnold, and his wife were living temporarily at Clouds Hill—tight quarters for a married couple—while Lawrence spent Christmas Eve of 1925 alone in Hut 105 at Cranwell, correcting the proofs of his book and reading T. S. Eliot’s collected poems, apparently content. On Christmas Day, he wrote to his mother, who had asked if he needed money, summing up his plans and his financial state:

No thanks: no money. I am quite right that way just now. How I’ll stand a year or so hence, when all the bills of the reprint of my book come in, I don’t know. The subscribers (about 100) have paid Ј15 each, to date. That is Ј1,500 more due from them. The expenses to date are Ј4,500. The Bank has loaned me the rest, against security from me. To meet the deficit I have sold Cape (for Ј3,000 cash + a royalty) the right to publish 1/3 of the book after January 1, 1927. And there will be American serial & other receipts, too. Probably I’ll come out of it well enough off. For his mother’s benefit, Lawrence oversimplified the immense task of printing the subscribers’ edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom.He also significantly underplayed the many difficulties he had imposed on Cape and his American publisher Doran over Revolt in the Desert,particularly by setting a limit to the number of copies of the abridgment that could be printed during his lifetime and thus eliminating for all practical purposes the possibility of a runaway best seller. In any case, he was determined not to benefit personally from either version of his memoir. This was high-minded but shortsighted—the two books would have made him a rich man, had he been willing to become rich. In this, as in other matters, Lawrence clung to his policy of renunciation. He very much wished to be recognized as a great writer, but—perhaps unlike all other authors—he did not want to profit from writing, or to endure (or encourage) the publicity that would inevitably accompany success.

The excellence of Lawrence’s relationship with the airmen of his flight can be guessed by the fact that he hired a bus to take them all, including Pugh, to the annual air show at Hendon, just outside London. As the deadline—March 1926—approached, he also got two of his hut mates to help him in the laborious task of cutting the text of Seven Pillars of Wisdomfor the abridgment, “as with a brush and India ink, [he] boldly obliterated whole slabs of text,” at night in Hut 105, and cutting the first seven chapters entirely, thus deftly turning the account into a very superior adventure story. His cuts were not only bold but painstaking and supremely confident; he made almost no insertions, or “bridges,” to link the text together, yet it reads so smoothly and seamlessly that one would never imagine it had been cut out of a much larger whole. No doubt Lawrence was guided to some degree by Edward Garnett’s previous abridgment,but his own version differed in some crucial ways. In particular, he eliminated the death of Farraj (which Garnett was reluctant to give up), partly because it required too many pages to explain and partly, one guesses, because the tone of Revolt in the Desertwas considerably more upbeat than that of Seven Pillars of Wisdom.Lawrence’s shooting the wounded Farraj to keep him from falling into the hands of the Turks was exactly the kind of moral ambiguity that he wanted to keep out of the abridged book.

In truth, Revolt in the Desert,though it is dwarfed by Seven Pillars of Wisdom,is a far more readable book. It opens with a bang at Lawrence’s arrival in Jidda—the first line is, “When at last we anchored in Jeddah’s outer harbour … then the heat of Arabia came out like a drawn sword and struck us speechless,” a very effective beginning—and it is by no means an insubstantial volume. The 1927 Doran edition is 335 pages long, or about 120,000 words. Interestingly, the author is identified on the jacket, binding, and title page as ‘T. E. Lawrence': the British-style single quotation marks are Lawrence’s way of suggesting that this person was mythical rather than real. Lawrence had many misgivings about putting his name on the subscribers’ edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom,and at one point decided to use the initials T.E.S.; but in the end, he opted to eliminate any mention that he was the author at all. Since all the copies are signed to the subscriber or to the person to whom he was giving the book, putting his name on the title page seemed to him unnecessary. This is perhaps the only case in literary history in which a major work has appeared with no indication of who the author was. Although he was still as opposed to bibliophiles as ever, Lawrence and his airmen aides went to considerable trouble to make every copy of the subscribers’ edition different, so that in some small way no two copies would be identical, thus keeping collectors busy for the next nine decades trying to spot and identify the differences. Some, of course, were easy—Lawrence had Trenchard’s “partial” copy (it was missing a few illustrations) bound in RAF blue leather, or as close as the bookbinder could get to that elusive color. He wrote to Trenchard: “It is not the right blue of course: but then what is the right blue? No two airmen are alike: indeed it is a miracle if the top and bottom halves of one airman are the same colour…. I told the binder (ex-R.A.F.) who it is for. ‘Then,’ said he, ‘it must be quite plain and very well done.’ ”

It was fortunate that Lawrence finished his labors when he did. In the spring of 1926, coming to the aid of a man whose car had been involved in an accident, he offered to start the engine and the man neglected to retard the ignition. The starting handle flew back sharply, breaking Lawrence’s right arm and dislocating his wrist. Showing no sign of pain or shock, he calmly asked the driver to adjust the ignition, cranked the engine again with his left hand, then drove his motorcycle back to Cranwell. In Flight Sergeant Pugh’s words, “with his right arm dangling and shifting gears with his foot, [he] got his bus** home, and parked without a word to a soul of the pain he was suffering.” The medical officer was away, and it was the next day before he could see Lawrence, who still did not complain. “That is a man!” Pugh commented admiringly. Although Lawrence recovered from this injury, later photographs often show him clearly nursing his left arm and wrist, and it seems safe to say that it gave him pain for the rest of his life.

By 1926 it was clear that Lawrence’s posting to Cranwell would soon have to end. One reason for this was RAF policy, which required that an airman must eventually be posted overseas—to India or Egypt for a period of five years, or to Iraq for two years (because of its vile climate). It would be impossible to send Lawrence to Egypt, where his presence would surely have a political effect—after all, he had been offered the post of British high commissioner in Cairo to succeed Allenby, and he was known to be in favor of greater independence for Egypt. Posting him to Iraq would be even more difficult; his friend Feisal was its king, and Lawrence’s presence there would cause consternation, besides stimulating the Sunni tribesmen to who knew what dreams of war and plunder. Nobody had forgotten how the tribes had ridden in from the desert crying “Aurens, Aurens” and firing off their rifles to greet him in Amman in 1921. That left only India, which was not an attractive proposition for Lawrence: he had done the government of India out of its ambition to occupy and control Iraq, and for that and other reasons was disliked by Indian officials, some of whom still bitterly resented the opinions he had expressed about them during his visit to Baghdad in 1916.

Trenchard offered Lawrence a chance to stay in Britain, but Lawrence was more realistic; the publication of Revolt in the Desert,of which 40,000 words would first be serialized in the Daily Telegraph(which had paid Ј2,000, or about the equivalent of $160,000 in today’s money), and the release of Seven Pillars of Wisdomto the subscribers would make him headline news again, all the more so because Revolt in the Desertwould be published in America at the same time. “It is good of you to give me the option of going overseas or staying at home,” Lawrence wrote to Trenchard, “but I volunteered to go, deliberately, for the reason that I am publishing a book (about myself in Arabia) on March 3, 1927: and experience taught me in Farnborough in 1922 that neither good-will on the part of those above me, nor correct behaviour on my part can prevent my being a nuisance in any camp where the daily press can get at me…. Overseas they will be harmless, and therefore I must go overseas for a while and dodge them.”

It was already clear that Seven Pillars of Wisdomwould be oversubscribed: the list of subscribers included, among writers alone, Compton Mackenzie, H. G. Wells, Bernard Shaw, Thomas Hardy, and Hugh Walpole; and among other notable figures it included King George V (Lawrence contrived to return the check for the king’s copy and make him a present of the book).** Lawrence declined to give the usual two copies to the Bodleian Library in Oxford and the British Museum Library, as was required for copyright purposes, having already donated the original manuscript to the Bodleian. This was an infringement of the U.K. Copyright Act, but being Lawrence he got away with it.

His last weeks in England were spoiled by another serious motorcycle accident, in which his latest Brough was badly damaged, but Lawrence sustained only a cut on his knee. He had to rent out his cottage, collect the books he wanted to take with him, and make his good-byes to the Shaws and the Hardys. The farewell to Hardy was a sad moment for them both. Hardy was eighty-six, and neither of them expected he would live to see Lawrence’s return. They stood on the porch at Max Gate in the cold weather, talking, and Lawrence finally sent Hardy into the house to get a shawl to wrap around his neck and chest. While Hardy was inside, Lawrence pushed his motorcycle quietly down to the road, started it up, and drove away, to spare Hardy the pain of saying farewell, and to spare his own feelings too, for he loved Hardy deeply. He sent his mother’s copy of Seven Pillars of Wisdomto his brother Arnold, to look after it until she returned to England; and he wrote to her in China, chiding her gently for staying there despite the danger, and warning her and Bob of the futility of “endeavours to influence the national life of another people by one’s own,” a reflection not only of his dislike of Christian missionaries, but of his own experience with the Bedouin.

He sailed for India on December 7, 1926, on board the Derbyshire,an antiquated, squalid troopship, packed with 1,200 officers and men, as well as a number of their wives and children, in conditions that shocked him. “I have been surprised at the badness of our accommodation,” he wrote to Charlotte, “and the clotted misery … on board.” Conditions were so bad that Lawrence wrote a letter of complaint about them to his friend Eddie Marsh, Winston Churchill’s private secretary, knowing that Marsh would pass it on. This became something of a habit with Lawrence—throughout his life in the RAF he made behind-the-scenes efforts to improve the lives of servicemen by bringing problems to the attention of those with the power to change things for the better. He persuaded Trenchard to drop many of the small regulations that plagued airmen’s lives unnecessarily—reducing the number of kit inspections to one a month, for example, as well as allowing airmen to unbutton the top two buttons of their greatcoat (unlike soldiers), removing the silly “swagger sticks” they were supposed to carry when in walking-out uniform, and abolishing the requirement to wear a polished bayonet for church parades. Lawrence wrote detailed letters about anything that seemed to him unfair, antiquated, or just plain silly, and in a surprising number of cases won his point, substantially improving the life of “other ranks.” Churchill was serving at the time as chancellor of the exchequer, and had already made the disastrous decision to return the pound to the gold standard, which many economists would later decide was the starting point of the great worldwide Depression; but at Lawrence’s behest he paused long enough to inquire into the conditions of shipping British service personnel and their families. Lawrence had an uncanny knack for bringing to the attention of those in high office conditions about which they would not normally have been informed, and getting them to do something. This was perhaps the only aspect of his fame that he found useful. His correspondence is full of injustices he wants corrected, or idiotic regulations he wants abolished. He served as a discreet and entirely unofficial equivalent of what is now called an ombudsman, and was responsible for a surprising number of commonsense reforms, including the abolition of puttees for airmen and their replacement with trousers, and the replacement of the tunic with a high collar clasped tightly around the neck by a more comfortable tunic with lapels, worn over a shirt and tie. These interventions were seldom, if ever, for his own benefit; nor did he mention them to his fellow airmen. He was always a master of the skillfully handled suggestion that allowed other people to take the credit, just as Bernard Shaw re-created him in the role of the omniscient, omnipotent Private Meek in Too True to Be Good.

As it happens, the conditions of life on board the Derbyshirewere shocking, though not unusual, and in describing them Lawrence provided unflinching descriptions of squalor and filth: the account of his experience as “Married Quarters sentry” is so painful as to be almost unreadable. His friend and admirer John Buchan said after reading it that it took “the breath away by its sheer brutality.” Buchan considered Lawrence’s power of depicting squalor uncanny, and said there was nothing in The Mintto equal it.

Swish swishthe water goes against the walls of the ship, sounds nearer. Where on earth is that splashing. I tittup along the alley and peep into the lavatory space, at a moment when no woman is there. It’s awash with a foul drainage. Tactless posting a sentry over the wives’ defaecations, I think. Tactless and useless all our duties aboard.Hullo here’s the Orderly Officer visiting. May as well tell him. The grimy-folded face, the hard jaw, toil-hardened hands, bowed and ungainly figure. An ex-naval warrant, I’ll bet. No gentleman. He strides boldly to the latrine: “Excuse me” unshyly to two shrinking women. “God,” he jerked out, “with shit—where’s the trap?” He pulled off his tunic and threw it at me to hold, and with a plumber’s quick glance strode over to the far side, bent down, and ripped out a grating. Gazed for a moment, while the ordure rippled over his boots. Up his right sleeve, baring a forearm hairy as a mastiff’s grey leg, knotted with veins, and a gnarled hand: thrust it deep in, groped, pulled out a moist white bundle. “Open that port” and out it splashed into the night. “You’d think they’d have had some other place for their sanitary towels. Bloody awful show, not having anything fixed up.” He shook his sleeve down as it was over his slowly-drying arm, and huddled on his tunic, while the released liquid gurgled contentedly down its reopened drain. The voyage from Southampton to Karachi took a month, and was sheer hell—"Wave upon wave of the smell of stabled humanity,” as Lawrence put it, so awful that even India, which he disliked on sight, seemed to be a deliverance. He was sent to the RAF depot on Drigh Road, seven miles outside Karachi, “a dry hole, on the edge of the Sind desert, which desert is a waste of land and sandstone,” a place of endless dust and dust storms, indeed, where dust seemed like a fifth element, covering everything, including the food. He was assigned as a clerk in the Engine Repair Section, where aircraft engines were given their regularly scheduled overhaul—easy work. The tropical workday at that time ran from 7:30 A.M. to 1 p.m., after which he had the rest of the day off. He spent most of his day in overalls; there was no PT; there were few parades; and his greatest problems were the lack of hot water to bathe in, and sheer boredom. Being on the edge of a desert filled him with both loathing and nostalgia—in the evenings, he could hear the noise of camel bells in the distance as a caravan made its way down Drigh Road. He did not leave the depot to go into Karachi; he had no curiosity about India at all. He spent his spare time sitting on his bunk reading the fifth volume of Winston Churchill’s history of the war, The Great Crisis;writing letters; brushing up his Greek; and listening to classical music on the gramophone in his barracks, which he shared with fourteen other airmen.

In February, the pictures he had commissioned at such great expense for the subscribers’ edition of Seven Pillars of Wisdom—oil paintings, watercolors, drawings, pastels, and woodcuts—were collected by Eric Kennington and put on display for the public at the Leicester Gallery, in London. Bernard Shaw contributed the preface to the catalog, declaiming, in his usual no-holds-barred style, “The limelight of history follows the authentic hero as the theatre limelight follows the prima ballerina assoluta.It soon concentrated its whitest radiance on Colonel Lawrence, alias Lurens Bey, alias Prince of Damascus, the mystery man, the wonder man,” and calling Seven Pillars of Wisdom“a masterpiece.” The gallery was packed for the two weeks of the show, with a long line of people waiting each day to get in. Although nobody but the subscribers could read the book, it was already creating a sensation. People eager to read it offered small fortunes in the classified ads of the newspapers for an opportunity to borrow one of the copies.