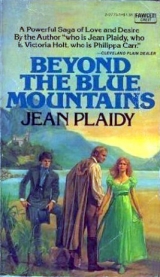

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 33 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“Who is she?”

The one they call Esther.”

“Esther.” said Mamma faintly. And then: “Of course, no man was sent.”

“Oh. but he said …”. “He is a liar,” said Mamma.

“Oh, but Mamma, I’m sure there is a mistake. I know he said I must ask him…”

“He has gone now.”

“I am going there again, Mamma. They asked me. He and Henry said I must go again.”

“You will never see them again,” said Mamma. Katharine was incredulous. She could find nothing to say.

“And,” said Mamma, ‘you will stay here for the rest of the day alone.”

Mamma went out then. She had been pale, but now her face was flushed, her eyes hard as the glittering stones in the pendant she wore round her neck.

Katharine heard the key turn in the lock. She was angry with Mamma, angry with Papa even, poor Papa who had done nothing but be very pleased because she was home again. Still, she was angry with the whole world, for more than anything she wanted to see Marcus and Henry again.

“And I will!” she said. She went over to the Bible on the chest of drawers, the Bible which Miss Kelly had given her last Christmas. She laid her hands on it and swore as she did when she and James played Judge and Prisoners. But there was no jest this; it was a solemn vow.

“With God’s help, so I will,” she said. Her eyes were resolute, her mind made up.

Carolan was dressing for her dinner-party. It was a very important dinner-party, a sort of coming out for Katharine. She was seventeen. Carolan’s thoughts must go back to a similar occasion nearly twenty years ago, when she was going to her first ball. A green dress she had worn; she was wearing a green dress now. How different though, this rather plump and still beautiful woman, poised and confident, the mother of five sons and one daughter, Mrs. Masterman of Sydney. How different from that slender girl who had gone down to the hall at Haredon to dance with Everard.

Audrey, her maid, was ready to do her hair. Audrey’s eyes, meeting hers in the mirror, sparkled with admiration. She had rescued Audrey from the kitchen, much as Lucille had rea her all those years ago, and the girl was her willing slave. _. could hardly remember now what Lucille had looked like, and yet the memory of her was as evergreen as the fir trees which had grown so abundantly in the damp climate of Haredon. There was everything to remind her in this house. Why did they not leave it? Simply because together they never broached the subject; they dared not. If she said to Gunnar: “Let us leave this house,” he would know she was thinking of Lucille. And what they had been trying to do all the time, all through those eighteen years, was to show each other, without mentioning the subject, that neither of them ever thought of Lucille.

It was a ridiculous pretence; she knew he thought of her often. She knew the shadow of his first wife lay heavy across the happiness he might have enjoyed with his second.

Audrey said: “Pearls, Madam?” And she smiled her assent. He: smile was charming as it ever was. She always tried to be charming to the servants, particularly if they had been convicts. Behind each of them she would see a grim shadow of Newgate that could make hideous memories rush back at her, and whatever had been their crime, she would make excuses for them. Of Audrey she knew little except that she was sentenced to transportation for fourteen years, and had, by all accounts, been a desperate creature. And yet here was Audrey, almost gentle, pliable, eager to please. She never asked questions of Audrey; it occurred to her that the girl might not wish to talk, but because there was a daintiness about her which most lacked, she had taken her to be her maid, and Audrey was grateful.

“Audrey clasped the pearls about her neck and stood back to admire.

They are lovely, Madam.”

A gift from Gunnar one of his many gifts. She was fond of him, though at times he irritated her almost beyond endurance. His ideas were so conventional that they bored her; she knew, almost to the phrase, what he would say on almost any subject. His conduct was absolutely what it should have been except on one occasion; and how ironical it was that her tenderness for him should be just because of that lapse.

She smiled faintly at her reflection in the mirror. Ripe womanhood, full sensuous lips, and green eyes that flashed from mood to mood with a speed that could be disastrous. She was her mother’s daughter; she belonged to that procession of women to whom numerous love-affairs were as natural as eating and drinking. But there was a certain strength in her which the others had lacked; perhaps it had grown up in the evil soil of Newgate, because that fetid air had nourished it. A glance from a pair of merry eyes, admiring, passionate and she was as ready for adventure as her mother had been. But she had resisted every time, for she could not forget that her husband had jeopardized not only his soul but and ironical as it might seem, this was of almost as great importance to him his position here in Sydney, for love of her.

Gunnar was really a man after Lachlan Macquarie’s own heart, and but for that eighteen-year-old scandal, what position might not Gunnar have held under the greatest governor New South Wales had ever known! Macquarie and his saintly Elizabeth had not been ruling when it happened, but there were those only too ready to tell him the story which they had preserved, as though it was something precious, through the reign of turbulent Bligh and the period of usurpation that followed before the coming of Macquarie. Gunnar admired the governor almost to idolatry; and the governor admired Gunnar; but that was that ancient scandal that had attached itself to poor Gunnar and dragged him down from the heights which, but for it, he would certainly have attained. It was not the fact that he had married a convict; it was the circumstances in which he had married her. There were many convicts, and once they were free it should not be remembered against them that they had suffered transportation. Everyone knew that the laws of the old Country, and its conditions, were such as to breed convicts. A convict can become a respectable man in a new country many of them had for that reckless daring which may have driven them to crime, turned to good effect, can be the very quality needed to found a new nation. No, the fact that Mrs. Masterman had begun her life in Sydney as a convict was not really as important as that clinging scandal about Masterman’s first wife.

And here I am, back at it, thought Carolan. Eighteen years ago it happened, and I still think of it as though it were yesterday.

Tonight was Katharine’s party, a joyous occasion. Katharine! Sweet daughter. Anything was surely worth while to have had Katharine. Five sons she had borne Gunnar, willingly doing her duty one pregnancy following close on another accepting the discomfort, the pain and the danger; and all because she was determined to do her duty, to give him those sons he had wanted. He had got them; he had paid dearly for them, and he should not be disappointed. Queer, that it should be Katharine whom they loved best of all. The daughter; and every time he looked at her, did he think as she did of those months immediately previous to her birth? Was it that that made her specially dear? No, not It was the charm of Katharine; the sweetness of her. Carolan’s daughter. Her eyes had lost that tinge of green, and were blue as speedwells you found in the lanes of the Old Country; her hair was a deeper shade of red; her chin determined as Carolan’s had been twenty years ago, so that one was fearful for Katherine. The boys were like their father calmer, assured; they possessed humour, though Gunnar had none, but that would not hinder their way of life. She could see them, years ahead, important men in the town, of perhaps in other towns, perhaps back in England. Martin and Edward both had a yearning for England. James would most likely take over his father’s activities; and it was too soon to see what little Joseph and Stephen were going to do. The boys were safe, but Katharine she was not so sure. Gunnar had wanted her educated in England; he had advanced ideas on education for such an unimaginative man. James was soon to leave for England, but Katharine she would not allow to go.

“But, my dear,” said Gunnar. ‘she needs more than Sydney can give her. There are things she must learn, which she can only acquire at home… the way to behave manners are necessarily a little rough here…”

“No,” she said, ‘no I should not have a moment’s peace. How do we know what would happen to her?”

She had had a frightful vision of life’s catching up reckless Katharine as it had caught up innocent Carolan. Newgate. The prison ship. But why should she be so caught, a young lady of substance? But how can you know what evil fate is in store!

She had her way. She remembered lying in the dark with him.

holding him in her arms.

“Gunnar, I could not bear it! What happened to me…” And he had soothed her and comforted her. Katharine should not leave her. It was for moments like that she almost loved him.

And now Katharine had grown secretive, her blue eyes full of dreams, her thoughts far away. You spoke to her and she did not answer; and she made no confidences in her mother. Sometimes Carolan thought she knew. Had it begun years ago when the child was only ten years old, and had disappeared one day and come back the next morning with Marcus ?

The thought of Marcus angered her, and comforted her and hurt her. So insolent he had looked, standing there in the yard. She knew he had kept the child purposely to hurt her, Carolan, that he wanted to hurt her as she had hurt him. Insolently he had looked at her, hating her and loving her as she hated and loved him. Gunnar had stood there, exasperatingly unobservant.

seeing in this man a kind friend who had looked after his daughter and brought her safely home.

It had seemed to her that Marcus’s eyes had said something else too, that they pleaded for a moment alone with her; they seemed to say: “Carolan, Carolan, we must meet again. Where, Carolan, where?” And her heart had beaten faster with excitement, and her need of him then was as great as her love for her children. He had seen that, and hope had leaped into his eyes. But Gunnar had been there, seeing nothing, his voice calm, his manner slightly pompous as he thanked Marcus with the charm and courtesy a successful man can afford to give to one who is not so successful.

“My dear sir, we are deeply indebted to you. We shall never forget…” And because he was such a good man, because he had always striven so hard to lead the right sort of life … no, not because of that. Because of that one lapse when for her sake … She let her thoughts swerve. Not that again! Not that. But it was the reason why she had turned from Marcus and ever since not known whether she was glad or sorry. All she knew was that her life was full of regrets … regrets for … she was not sure what. Life was a compromise, when for people like herself and Marcus who knew how to live recklessly, it should have been glorious. Up in the heights, and perhaps occasionally for Marcus could never be faithful to one woman even if she was Carolan down in the depths. But never, never this unexciting, boring level.

And that day when Marcus had come into the yard with Katharine was a bitter day, for it had lost her something of Katharine. She had been too harsh with the child, blaming her because she had stupidly wanted to blame someone for that for which she herself was entirely to blame.

“You shall never go there again!” she had said, and Katharine had answered with stubborn silence. If your daughter was so like you that the resemblance frightened you, you could often guess her thoughts. She had gone there, of course she had gone. She had felt the irresistible charm of Marcus. There was a boy, Henry … Esther’s child. He would doubtless be as like his father as Katharine was like her mother.

The child often absented herself all day. She would ride off in the morning and not return until sundown. Where had she been? She would come back, flushed with sunshine and laughter, and happiness looked out of her eyes. And when there had been that talk of going to England, how stubbornly she had set her heart against it!

“I do not want to go to England! I will not go to England!” Why? Because, if she went, she would miss those long days when she absented herself from her own home and went to that of Marcus.

Carolan had seen the boy, Henry. He had inherited that subtle attractiveness from his father. He was young and crude of course, but it was there, and Katharine possibly did not look for polish. Dark he was, dark as Marcus, with that quickness of eye; she had heard him call to someone in the town, and his voice had that lilting quality which belonged to Marcus’s.

Katharine was young, only just seventeen. It might be that she thought she loved the boy, because it was the first time anyone had talked of love to her. So she had contrived to arrange parties for her, gatherings where she could meet charming people. That was not difficult, for Sydney was no longer a mere settlement, Macquarie had vowed it should take its place among the cities of the world, and surely he was keeping his word. From the Cove it looked magnificent nowadays, unrecognizable as that notch potch of buildings it had been on her arrival. It was gracious and stately; large houses of hewn stone had taken the place of the smaller ones, and the number of warehouses had grown on the waterside to keep pace with the growing population and prosperity. Sydney would soon grow into a great town, busy and beautiful. There were young men of substance in the town who had shown signs of becoming very interested in the fresh young charms of Masterman’s daughter; and not least among these was Sir Anthony Greymore, recently out from England, a young man, sophisticated and charming, wealthy and serious-minded enough to make a good husband. He surely, if anyone, could wean Katharine from Henry.

I will not let her marry Marcus’s son! thought Carolan. I will not! Even though, for a time, she thinks her heart is broken. He will be like his father. I see it in him.

Audrey was looking at her oddly, comb poised.

“I am sorry, Audrey. I am fidgeting.” Audrey’s eyes in the mirror worshipped her. Where else could a convict find such a kind mistress?

Gunnar came in. He had just ridden home. He looked tanned and healthy. He was in a hurry for he was late, but he would be ready at precisely the right moment when he must descend to greet his guests. He would never be late. His dressing-room would be in perfect order and he would know just where to find everything. How wrong it was to get exasperated over someone’s virtues!

Audrey had finished her hair and the result was most attractive.

“You don’t look much older than Miss Katharine, M’am. You might be her older sister. People could easy take you for that.” What flattery! She looked years older than Katharine and most definitely she looked Katharine’s mother.

She felt an acute desire to be Katharine’s age, to be going to her first ball where she would be told by Everard that he loved her. Had she known what was waiting for her. how she would have pleaded with him to let nothing stand in the way of marriage! Had she never come to London she would never am known Marcus. She could not wish that. No, perhaps if she could live her life again, she would go back to that day when Margery had told her that Clementine Smith and Marcus were lovers.

She shrugged her shoulders impatiently. Had she not been fortunate? The life she had shared with Gunnar had dignity, security; and life with Marcus would never have given her either.

Gunnar came in from his dressing-room; he wanted to talk to her, she could tell by his manner, so she dismissed Audrey.

“Well,” she said, playing with her fan of green tinged ostrich feathers.

He smiled at her, admiring her beauty which never failed to stir him, admiring her adroitness in dismissing Audrey without his having to tell her that he had something to say.

“I was late,” he said, ‘because I met young Greymore. He asked .. for permission to approach Katharine.”

“And most willingly you gave it!”

She laughed, and he laughed too, though he was never sure of her laughter. To him this seemed a matter of the deepest gravity; the betrothal of their daughter was surely no matter for laughter.

“I gave it, of course,” he said.

“I hope she will accept him,” said Carolan pensively.

“I should hate it if she were reluctant.”

“I was wondering if we should warn her, and tell her what our wishes are.”

Dear Gunnar! Did he know his daughter so little that he thought they had only to tell her Their wishes and they would immediately become hers?

“She may be difficult,” she warned him tenderly.

“She is very sensible,” he said.

“And it is a good match.”

She stood up then. He was sitting on her bed. She took his head and held it against her breast. He was always moved by these sudden displays of affection; they were so unexpected. Why should she embrace him now, while they were discussing this very important matter of their daughter’s marriage?

She said: “You think everybody can be as sensible as you, my dear.”

“Oh, I think Katharine has her share of common sense.” Oh, no! she wanted to say. There is no great common sense in our Katharine, because she has little of you in her; she is all mine. Reckless, adventuring. And yet there was a time when you… “Gunnar,” she said, ‘if she refuses him, what then?”

He said confidently: “We will talk to her. He is very eager. He seems to me the sort who’ll not take no for an answer.”

“She worries me, Gunnar. Sometimes I wonder whether she has not formed some attachment.”

“But, Carolan, with whom?”

“How should I know.”

“But surely there would have been some evidence…”

He did not see the evidence of bright eyes, of that absent manner, of that shine of happiness. He would never see that. Blind Gunnar. How did he ever love blindly himself?

“I am determined,” said Carolan fiercely, ‘that she shall make the right sort of marriage. I think she needs that sort of marriage. The boys will choose wisely… one feels that instinctively. Or if they do not, it will not be so important. But Katharine …”

She saw his face in the glass, and she knew he was thinking of the coming of Katharine; how she, Carolan, had talked of marrying Tom Blake; he was remembering it all vividly, for it lay across his life as darkly as it lay across hers.

She turned to him then, clinging to him in sudden tenderness.

“Oh, Gunnar, you have done so much for us all. You have made me so happy.”

“My dear!” he said in a husky voice. But the shadow was still in his eyes. Lucille was there.

Margery knocked at Katharine’s door and tiptoed into the room. Katharine was standing before her mirror, admiring herself in her blue ball dress with its masses of yellow lace. Audrey, before starting on Carolan’s hair, had dressed Katharine’s and it hung in curls about her shoulders. Margery clasped her hands together and rocked herself with delight.

“My little love! My little dear. The men will be at your beck and call tonight!”

“How your thoughts run on men!” said Katharine, and Margery cackled with glee.

She was more outspoken, this Katharine, than her mother had been. Not quite the same brand of haughtiness. Ready to enjoy a little joke. And up to mischief, if Margery knew anything!

“Pity Ac isn’t going to be here tonight!” Margery nudged her.

“Who?” said Katharine defiantly.

“You know who! Him who you sneak out to meet, me darling. Tell old Margery.”

“You know too much.”

“Well, what’s an old woman to do? The gentlemen don’t come calling on me now, you know.”

“You must not tell, Margery. You haven’t told?”

“I’d cut me tongue out rather.”

“Only sometimes I’ve thought that Mamma seemed to know. Margery, if you told I’d never speak to you again!”

“Not me, lovey. Not me! And if she was to know, what of it? Do you think she’s never …”

She could silence with a look, the little beauty, and her with a secret on her conscience too! Old Margery had seen him. He was forever hanging about the yard, he was. And there was no mistaking where he’d come from; the look of him told you that. And his father all over again! He knew how to get round a woman, no mistake, and he’d got round her little ladyship till she was yearning for him. The things you could find out, if you kept your eyes open!

Margery finished lamely: “A pity he can’t come here tonight! Pity he can’t be introduced to your Ma and the master, and we can’t hear the wedding bells ring out! That’s how I’d like this to end.”

“Parents,” said Katharine, ‘have such ridiculous ideas!”

“Parents was young once, me lady!” Ah! That they was! And well I remember the two of them. Madam Carolan. flaunting herself in her mistress’s clothes, and you, me lady, well on the way before you should have been. And that… what I don’t like thinking of… and me having a hand in it, so’s I’m frightened to show me face on that first floor. I wish we’d get out of. this house. But ghosts don’t mind where you go; they follow. And they don’t need a-carriage, nor a stage… not they! And as sure as I’m Margery Green there’s a ghost in this house, though I ain’t and God forbid I ever should clapped eyes on it!

“Yes, Margery, but they’ve got this Sir Anthony in mind.”

“Ah! Marry him, me pretty dear, and you’ll be a real live ladyship. There’s some who.wouldn’t say no to that, I’ll be bound!”

“I thought you’d talk sense, Margery!” Sweet balm, that was. Madam and the master, they didn’t talk sense, but old Margery did, according to this lovely bit of flesh and blood. Margery put her hand on the bare shoulder, though it was risking her ladyship’s displeasure, for she was never one for being touched … except by some most likely … I never saw a child take after her mother more. And why not, and who are they to say her nay? What of them, eh? With the mistress lying in her bed, poor sickly lady. No, no, don’t think of that, Margery; it ain’t nice to think of. I wish we’d leave this house, but would that be any good? Ghosts don’t need the stage.

“Look here, my dearie, love’s a game for them that plays it. It’s not for them outside to give a hand. That’s Margery’s motto.”

“I agree, Margery!”

How her eyes flashed! Trouble coming, dear as daylight. Mrs. Carolan born again. Imagine telling her all those years ago who she was to love! Funny how people forget what they were lite when they were young! Now Margery Green, she remembered all too well!

Katharine had dreams in her eyes; she was thinking of long days in the sunshine, riding out to the station; he came to meet her. At first he had pretended to think her just a foolish girl when together they had listened to Marcus. But when the Blue Mountains had been crossed, they both seemed to grow up suddenly. Marcus, deeply regretting that he had not been one of the gallant band that first crossed the mountains, told them the story in his inimitable way, and it was as exciting as though they themselves had found the road.

“No matter how difficult a project may seem,” said Marcus, ‘stick to it, and you’ll get across as sure as men got across the Blue Mountains!”

She had ridden out to them, and kept her secret; she had planned and contrived, and it had been worth it. How she loved the sunny veranda and the talk of the two of them! Marcus smoking his Negrohead, drinking his grog, watching them, loving them, talking to them, welcoming her into his home. Sometimes he called her Carolan.

“That’s my mother, you know. I’m Katharine.”

“Of course! Of course! I forgot. I used to know your mother once.” And she had felt resentful towards Mamma, who, for no reason at all, had taken such a dislike to him, doubtless thinking him lacking in culture because he was not dabbling in politics, and did not attend the local functions, and was as different from Papa as it was possible for any man to be. Was Mamma perhaps a little snobbish? Her values were wrong surely since she tried to prevent her daughter’s friendship with a man like Marcus. She knew that Mamma had come out on the transport ship; she could not help knowing. One of the girls at school told her; it was a great shock. It made her look upon convicts in a different way; at one time, she feared, she had thought them sub-human.

“Are convicts real men and women?” Martin had once asked. She had been rather like Martin. But Mamma had been a convict, and Marcus and Esther. Convicts were ordinary people, and two of them Marcus and Mamma were among those she loved the best in the world. So Mamma should not have been snobbish about Marcus. She felt a slight estrangement between herself and Mamma then, but afterwards when she drew from Margery the story of the First Wife, she warmed to Mamma again. Poor Mamma, a servant in this house where now she was mistress, and Papa unhappy with his first wife! What a different picture from the house as it was today, and how proud Mamma must have suffered! It was really a good thing when the First Wife died, and Papa discovered that he loved Mamma. Vaguely from a long way back she remembered a certain fear about the First Wife. What an inquisitive and imaginative little creature she must have been in those days! Probing; scenting mystery; drawing out Margery and Mamma and anyone who would respond in the smallest way! Then she had discovered Henry and Marcus, and the house with the veranda and they filled her thoughts. She did not remember thinking very much about the first floor after that.

What would Mamma say if she knew she had been present at their musters! Papa too! But what a thrill to ride beside Henry!

“You’d better keep close, young Katharine.” That was Henry before he knew he loved her.

“A bullock on the run can be pretty savage. Keep near me!” That moment when the bull dashed into the plain with the cattle at his heels hundreds of them; she longed to join with them, with Marcus and Henry and Mr. Blake. She would one day. They would not let her at first; they said it was dangerous. She loved to hear the crack of the stock-whip, to see the skill with which they guided the cattle in the direction they must go. She was enormously proud of Henry. And then one day they let her join in, and it was after that that Henry gave her his first present, a stock-whip with a myall handle that smelt like violets.

She longed to stay at the station with them, to sit on the veranda with them till darkness came; to listen to the singing of the sheep-washers when their day’s work was done, and to heat the talk of the knockabout men who came for the shearings of to do odd fencing jobs. She would have loved to come in after dark with Henry, just the two of them alone, and cook their own meals … beef steak or bacon, or perhaps, after a muster, a fat calf.

Marcus had promised them their own station when they were married. They could go to it now … if they were married. Marcus would put no objection in the way. It was possible to discuss all one’s plans before Marcus. He never attempted to foil you; his suggestions were helpful, not destructive.

He said: “You’ll be my daughter, Katharine. Fancy that. I wished you were my daughter right from the very first moment I saw you!”

He was a darling. If it would not have been so utterly disloyal to Papa who really was the best father in the world she would have told him she would have loved to have him for a father. A father-in-law was almost a father anyway. She flung her arms round his neck and kissed him when he told them about the station. He liked that … and yet, oddly enough it embarrassed him. He said: “Katharine, Katharine! My sweet little Katharine, I’d have given twenty stations for that.” One didn’t always believe all he said. That about giving twenty stations for a hug was just his way of telling you how pleased he was. Perhaps all of his stories weren’t exactly true, but that didn’t matter; he made them more exciting because he knew you liked them that way. He spoke her name oddly, slurring it, making it a mixture of Carolan and Katharine; there was a similarity between the two, and he had a curious way of rolling them into one. She loved him next to Henry and Mamma and Papa, and there really was no one like Marcus in the whole world.

Henry’s mother she could never like, and she believed Henry’s mother did not like her and did not really want Henry to marry her; Katharine believed she protested to both Henry and Marcus.

Not that anything would stop them. She and Henry were meant for each other; Henry was as sure of that as she was. When she had lain with her ear to the ground; when she had coo-eed over the bush, she had been on the threshold of a new LIFE. Well, she knew that now I His eyes burned when he looked at her. He was eighteen. Papa would say: “Good gracious! How very young!” But Papa just did not understand.

She could recall indeed she could never forget the wonder of that day when Henry ceased to think of her as a little girl, and thought of her as Katharine. It was the day he had given her the stock-whip, and that gift represented more than the mere adventure of a muster shared; it was the adventure of finding each other. She was fourteen then. He was fifteen, but he seemed a good deal older; he had seemed a man when she first met him, and he had been little more than eleven then. They were shy at first, and Marcus knew why! He watched them with amused tenderness, and encouraged them to love each other.

She was sixteen when Henry said he loved her. It was there in that spot where he had first found her, and how deeply she had been touched by that sentiment which had led him to tell her there! They had lain on the harsh grass, and she had heard his heart beating, where once she had listened to the thud of his horse’s hooves.

He talked of their life together, and she saw the station they would share; she loved the life he lived; it was the only life for such as they were. Fresh air, sunshine, and a new life beyond the Blue Mountains where the town of Bathurst was beginning to grow, and where the land was good, with grazing for millions of sheep.