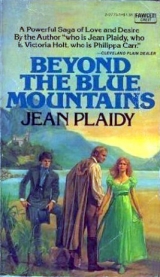

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“How I wish I could feel so pleased with life, and all for a cast-off dress!”

“Shall I give you your pills now?”

“No, I think I will have a draught of the tonic.”

Carolan poured it out, her fingers itching to get to work on the dress. She smoothed the pillows. She picked up the dress and set to work. She let it out a little; she lengthened it. And all the time she talked soothingly to Mrs. Masterman of her grandmother’s illnesses. For an hour she worked on the dress; she slipped out of her own and tried it on. The change was effective. Never again, thought Carolan, shall I wear that hideous convict’s yellow.

Mrs. Masterman began to be nervous.

“What will the master say?”

“Do you think he will notice?” asked Carolan, slyly.

“Perhaps he will not,” said Mrs. Masterman.

“Read to me a little, Carolan.”

She read, but she did not know what she was reading; she was longing to get down to the kitchen, to flaunt her new dress. Margery’s face! Jin’s, Poll’s, Esther’s! She hoped Marcus would look in at the window. She laughed inwardly. Life was turning out to be quite amusing after all. What other woman, arriving on the convict ship, had found such an easy way of life as she had! What others would be wearing a green afternoon frock such as this! Some of those in the brothels perhaps. What a life! She did not need to use her body; she could use her brains.

Mr. Masterman came in while she was reading. He often came in while she was there. He saw her in the green dress, her red hair falling about her face. She smiled at him demurely, yet with a challenge daring him to suggest it was not in order for her to wear it. He said to his wife in his clear, pseudo-cultured voice: “How are you today?”

“Much the same I’m afraid, thank you.”

“The Jenkinsons want us to dine there tomorrow if you are well enough.”

“I rather doubt that I shall be.”

“I thought so.”

He stood by the bed. Carolan busied herself with her sewing, but she was aware of his attention focused on her, and she knew that the words were spoken automatically; he was not thinking of the woman on the bed, because he could not tear his thoughts and eyes away from her.

He went out.

Mrs. Masterman said: “He did not say anything. I do not believe he would notice anything outside business. He is a most unobservant man!” Carolan was silent.

“Although,” went on her mistress, “I did think I saw him looking in your direction rather curiously.” Carolan laughed. That was the supreme moment of. triumph.

She was the real mistress of the house; mistress of them both if she cared to be.

The girl, Margery told herself, was intolerable. What airs! Who ever heard the like? A convict, not three months in the house, and riding rough-shod over all! She had come to giving orders in the kitchen!

“Mrs. Masterman will not like the table laid this way. Mrs. Masterman hates dirty glasses!” Mrs. Masterman this and Mrs. Masterman that! Then Mr. Masterman … “Mr. Masterman is asking some friends tonight. This is the menu.”

Who was in charge of this kitchen? That was the question Margery wanted to ask.

Once it was not Mrs. Masterman nor yet Mr. Masterman, but II “I cannot have these flowers any longer in Mrs. Masterman’s room. The water positively stinks!”

The airs! The graces! Wearing the mistress’s cast-off clothes. Oh, she had bewitched the mistress completely. But what was wrong with the master? Why didn’t he put down the foot of authority?

If you ask me, said Margery into her glass of grog-for whom else had she to talk to, with Jin, the slut, for ever creeping out to the backyard for a word or something more with James, and Poll with her slavering mouth and her doll, little more than an idiot, and Esther walking on air because she was in love? -if you ask me, he’s only too glad to quieten the mistress; he’d put up with anything, even a convict servant, flaunting all over the house.

Oh, but she was lovely! So lovely it did something to your inside to watch her. Made you think of years and years back, and wish you were young again. And what was the -good of getting angry, wouldn’t most women have been the same?

Funny it was to see what love did to people. Herself and James, Jin and James, Poll and her doll, Esther with that Marcus, and Tom Blake with Carolan.

People do funny things when their emotions are aroused -didn’t she know it! She hadn’t known life and known men for nothing. And when you have been young and full of adventure, it comes hard to take a back seat. Fun too to try your hands at working things… not necessarily the way you want them to go, but just poking about here and there … a jerk at this one, a push at that… It gives a feeling of being something more important than just an old woman taking a back seat by the chimney corner, grumbling into her grog.

Pride goeth before a fall, Miss Carolan, and you’re mighty proud; the proudest piece I’ve ever clapped eyes on. Oh, but so lovely to the eyes, soft skin and budding beauty, and eyes of green behind whose haughtiness passion could burn and tenderness glow. It wasn’t surprising that Marcus loved her, and Tom Blake loved her, and the mistress had got interested in her. But she was walking with her head in the clouds, the silly puss, who thought herself so sly, she didn’t watch her steps. You had to watch your step all the time in life. When you were eighteen and so beautiful your head got tilted too high so that you couldn’t see the ground, you didn’t know so much, you weren’t so very wise and the trouble lay in the fact, that you thought yourself the wisest soul on earth. Now Marcus, he wanted her sure enough, for all his goings on with the other, but he was a man who could love halt a dozen women at once, and that sort has to be watched. And Tom Blake, he might be the faithful sort, but he wasn’t her sort; she’d tire of him in a month, that’s if she ever liked him enough at the start. And the graces of a mistress are like a house built on shifting sands … there right enough one minute, and gone the next.

Margery laughed so much that tears fell into her puddings. Her eyes were beady, black and sharp as needles. There were things she had suspected for a long time. She bided her time, waiting; it was good fun waiting. Is it? No, it ain’t. By God, it is! By God, I’m sure it is!

This is funny. It ain’t the things that happen; it’s the people they happen to. It’s people that make the drama and the comedy, not just events. It’s her and him, and her again. Oh, this is funny; this is side-splitting! Serve her right, the proud hussy. Esther the mealy-mouthed, the prayer-maker looked strange these days, peaked and frightened, exalted, queer. Her face beneath that cloud of glorious hair was drawn. She was frightened.

Is it? No, it ain’t. But it is Of course it is!

Oh. Mistress Carolan, Mistress Carolan! Here is a shock for you!

Tell her today No, wait a little. Store your secret. Have fun with it, play with it. How to begin? Not an expression of her face must be lost, not an inflexion of her voice.

She came into the kitchen one late afternoon; she was wearing the green dress the mistress had given her and allowed her to alter. It was tight across her breasts and it made her skin glow and her hair, glossy from the brush, hung about her face. She walked like a lady… and her a convict, a thief I But Margery always softened when she was there, liked to watch her eyelashes sweep up and down, liked to stroke the soft skin of her arms: her hands were whitening, growing soft, and she, unbelievable insolent, used the mistress’s polish on her nails. When she was there, Margery put off telling; there were times when she felt she could not bear to hurt her, when she liked to listen to her all but giving orders, liked to watch the proud tilt of her head.

She said now: “Well ducky, have a cup of tea, will you. love? I’ll tell Poll to make it.”

“I cannot stay,” said Mistress Carolan.

“I have to be upstairs.”

The airs! The graces! Too good to drink a cup of tea at Margery’s table, Margery who had been good to her when she had come from the ship a poor, lousy, shivering creature!

“A word in your ear,” said Margery, a dull flush rising to her cheeks.

“I have not very much time to spare,” she said.

You’ll have time to spare for this, me lady! Margery looked through the window to where Esther and Poll were pumping water in the yard:

“It’s what the master will say that worries me. I always thought Jin would be the one. I didn’t think it would be her.”

“What do you mean?”

“What ain’t you noticed?”

“Noticed what?”

“What’s happened to her!” She nodded through the window at the two girls at the pump.

“Poll?”

“The other one.”

“Why,” said Carolan, ‘what has happened?”

“Can’t you see? You’ve got eyes in your head, ain’t you? Oh, I know what it is, them eyes is too busy upstairs to notice what’s going on down here among us humble folk.”

“Esther…”

“She fainted clean away yesterday. Where’s your eyes, girl? But, deary me, I reckon a lady wouldn’t be noticing such things.”

“Esther…” said Carolan again. ‘… has been up to what ain’t respectable. That’s about the long and the short of it.”

Carolan turned on her.

“You’re a coarse old woman! Esther fainted then she is ill. How can anyone endure this sort of life …?”

“Well, there is them that gets themselves a place upstairs, but it ain’t so good for us ordinary folks, that I will admit. But if ever I see a girl in trouble, I see one now.”

“But Esther… Esther… it isn’t possible! She…”

“Ah! It’s the quiet ones what go wrong: I’ve seen it before. One little slip and down they go, sliding down to perdition. Whereas our kind … you and me …” She nudged Carolan, winking one eye.

“I don’t believe it.”

“It’s true as I stand here. I got her round all right. I had a good look at her. I wasn’t born yesterday. I know a pregnant girl when I see one, and I saw one yesterday. I sent the others out, then I made her tell me. All she could say was that she loved him and there didn’t seem nothing wrong in it at the time. That’s what they all say”?

“Marcus!” whispered Carolan.

That’s about the ticket. Been hanging round here a lot, he has. He’s artful as a monkey, he is. It wouldn’t be easy for a girl like her to say no to him. You see, he knows just how to get round her, him … going all religious-like just to make her feel everything’s all right, and talking about love being beautiful and sacred. I reckon; and then she gives way… that’s how trouble starts.”

Margery watched her. She had to admire her. Her face was blank and white, so that you wouldn’t know what was going on behind her eyes. They were hard and bright like precious stones. And how they glittered.

That’s got you, my fine lady! That’s pricked your pride. Thought he was all for you, didn’t you? Thought he couldn’t look at anyone else. You’ve got a lot to learn, my pretty. Men is men all the world over.

Carolan went past Margery right out into the yard. She went to Esther, and the way she dragged her from the pump showed what she was feeling. She could have murdered the girl, it was clear. She was wishing she had never met her.

That would teach her to give herself airs. Oh, but so lovely she was, lovelier in her rage than she was when she was soft. And just because she held her head so high, it made you want to cry for her, made your inside go all funny. It seemed there was some evil blight on her lovemaking. First that parson who didn’t move a hand’s turn to save her. Then Marcus, who was mad for her, and yet couldn’t keep himself straight for her. There’s men for you! Not worth a penny piece, the whole boiling of them. Ruining a girl’s life like that. Oh, she was wild! Oh, she was angry! She was sad too. She was flaying the girl with her tongue. pouring contempt on her. Sly thing, all that praying, and then to go behind her dear friend’s back… Margery wiped a tear away from her eyes. It was something that couldn’t be helped. Margery had seen it coming. The girl’s blossoming, washing her hair under the pump till it was all shining and made little curls all round her forehead; watching the window for a sight of him, listening for his step. A woman can’t have such goings on in her kitchen and not get a bit of a kick out of it herself.

That evening, that was the beginning. Her ladyship flouncing down for something or other and seeing Marcus there at the table drinking a glass of ale, and her looking at him like he was a bit of dirt beneath her feet, when all the time she was jealous because he was sitting so close to Esther. She didn’t stay in the kitchen; she went upstairs again. And the way his eyes followed her, started making your own water. She was just a child really. Seventeen. It ain’t so easy to remember what you was at seventeen. Pretty silly… making a fool of yourself. Well, that was what Mistress Carolan had done … made a fool of herself and Esther and Marcus too for that matter. Him and her! What a pair! They rushed at life; there wasn’t any sense in rushing at life; you came a cropper sure as you were born. There was her ladyship wanting him, and there was him wanting her. But no, she has to be all pride and dignity just because he let a woman keep him to get started on his way of life; and he has to show his anger with her by pretending to be interested in someone else. If you’ve been young and in love yourself, you know. Silly children! Want a good smacking, both of them.

She had made Esther drink gin that night, a lot of it. It was easy enough to keep filling her glass. And he had drunk too, and got reckless, and that was the beginning. Esther was pretty enough when she was lively, when she wasn’t saving her prayers, when she was wanting a bit of life like other girls wanted. He was never the man to miss his opportunities; it was as natural and easy as eating and drinking to him. He was made that way. That was how it happened … and give young people a taste for that sort of thing, and there you are. They don’t stop at once… not if she knew anything about it! And there was her ladyship, tripping about upstairs, getting dresses out of the mistress, altering them, like some queen’s favourite, making her lover wait a while to show her displeasure. Ha! Ha! It was funny, whatever way you looked at it.

Carolan came in from the yard. She looked like a sleepwalker, with all the life taken out of her.

“Now, lovey,” said Margery, ‘it don’t do to take these things to heart, and all this keeping a man waiting never did pay, to my mind.”

But she had walked through the kitchen as though Margery was not there.

“Draw the curtains, Carolan. I think I will have a rest for a while.”

“I will leave you, M’am; you will rest better without me.” Her voice was hard, determined. She could not stay in this room; she could not bear it. She would scream, be rude to the woman, would cry out: “Oh, stop talking of your silly ailments! What do you think I am suffering … I have lost Marcus! First Everard Then Marcus!”

“I wish to turn out one of the cupboards in the toilet-room. If you need me, you can knock on the wall.”

Docilely Lucille Masterman nodded, and Carolan went out.

She looked at herself in the long mirror. How strange she looked! If that selfish woman in there had been the least bit interested in anything but herself and her silly medicines she would have noticed. There was no one to condole with Carolan. Margery was laughing up her sleeve. Esther could weep till she could not see, but she was weeping for herself and her predicament. Esther! The virtuous Esther whom she had looked upon as something near a saint, creeping out to him like a servant girl. Esther! Her friend no longer. She wished she had never seen her, never listened to her whining voice. Esther and Marcus. Marcus and Esther. Together. Making love.

“I hope you said your prayers, Esther, before you began!” The words had made the girl flinch, and serve her right. Sly, deceitful little hypocrite! And Marcus, the beast! She was well rid of him. Had she married him, what would her life have been? He would not have been true to her for a week. I hate them both. I hate them. She had said: “Mr. Masterman will be furious when he hears. He will want to know how it happened, who the man is. He will want to know how you came to be entertaining convicts in his house. I would not be in your shoes, Esther.” She had had the satisfaction of hearing Esther’s strangled words “I wish I were .dead.”

Weak, snivelling Esther. What will become of her now? What will Mr. Masterman say? Momentarily she tore herself away from her sorrow to visualize the man. Cold profile, eyes that could glow warm enough for her; but his sort, when they knew what it meant to feel desire, were harsher to those who gave way to it.

I would not be in your shoes, Esther! But she would, of course. She, who loved Marcus, would have given a good deal to be in Esther’s shoes, bearing Marcus’s child, having been loved by Marcus.

Why does everything go wrong with me? she asked her, reflection. First Everard, now Marcus. Why, why?

The answer was there in the headstrong line of her jaw, in the tilt of her head, in the shine of her eyes. She herself was the answer, and the losing of Marcus was more her own fault than anything that had happened to her.

She wanted Marcus, She loved Marcus. Only now did she know how much. Only now when it was too late; for it was too late. She must face that. She could never marry Marcus now. How could she? When Esther was to have his child.

Let Esther have the child; what did it matter? Queer thoughts darted into her mind. There was a doctor, an ex-convict; he had helped Mrs. Masterman why should he not help Esther?

No! Let Esther find her own way out of her difficulties. She would not help her. She imagined Esther, standing before Mr. Masterman, explaining her guilt What would happen to Esther! Who cared what happened to Esther! Esther had acted without thought of the morrow. Let the morrow take care of itself. All right, let it!

And meanwhile, what of herself? Lonely and sad, loving Marcus who did not love her whatever he might say. she sank down on a pile of clothes she had turned out of one of the cupboards. All her pride left her. and she sobbed brokenheartedly.

Quite suddenly she was aware of not being alone. She turned slowly, saw first his shapely legs in well-cut riding breeches, his good though sober coat, his fair face pale like a statue she had seen carved in stone at Vauxhall Gardens.

He did not move; he was embarrassed. He said: “I am afraid you are very unhappy. If there is anything I can do to help…” She smiled sadly and shook her head.

“There is nothing, thank you.”

“Oh, but surely there is?”

He knelt down on the pile of clothes beside her.

“You are very kind.” she said, and she thought, for seven years I shall stay here working in this house, for him and the woman in there. There will be no hope of escape now. And she realized how, even while she tossed her head and refused to be friends with him she had been longing for reunion with Marcus, for the life he had talked of, on the station. The thought of her blind folly set the tears gushing out of her eyes again.

“Oh, come,” he said, “you must not be so upset. Will you not tell me your trouble?”

She saw the pulse hammer in his temple, and she knew that his general serenity was disturbed by close contact with her.

“It is nothing…”

He was still kneeling. He put out a hand to touch her shoulder.

“My poor child,” he said.

“How old are you?”

“Seventeen!”

“It is very young.”

“It feels old,” she told him, and her mouth quivered.

“Just over a year ago I was young. Now I am old.”

“You must tell me about it. Oh … not now, when you are feeling better. It is a momentary depression, I believe. Yesterday I thought you were the gayest person I had ever seen in my life.”

There was great satisfaction in such solicitude. She began comparing him with Marcus. There was the same eager burning light in his pale eyes as there had been in Marcus’s blue ones, but there any resemblance between them ended. Here was an upright man, kindly though cold. He seemed very youthful in his eagerness, although he was probably older than Marcus, but not old in experience; in experience, just a boy.

She put out her hand and he took it.

She said: “I cannot think why you are so good to me.” Which was untrue, for she knew full well.

He gripped her hand more tightly, and said: “It grieves me very much that you should be unhappy here. You are homesick perhaps.”

“Nor she said.

“No!” Defiance returned to her eyes; they glittered behind the tears.

“I do not feel homesick.” do not care if I never see England again. Why should I want to? What are trees and grass? Are they England? There are trees and grass here. No. England is Newgate, cruelty, injustice. I do not care if I never see it again.”

“How badly they have hurt you.” he said.

She nodded. He drew her towards him.

“I am so sorry. I have wanted to tell you so before.”

She lifted her, face to his, until their lips were very close. She thought, Marcus is finished now; I will remember nothing of him except his rogue’s philosophy. I will never love anyone again as long as I live.

He was staring at her. In a moment he would kiss her unless she moved away. She only had to repulse him once, and he would keep right out of her way for evermore; he was that sort of man. Now he was fighting with himself; he was thinking, I must not; I must get rid of this mad infatuation for one of out servants, a convict of whom I know nothing except that she is beautiful and more than beautiful.

Let him escape, and he would disappear for days; he would go to church and hold his head high and thank his God to have been delivered from temptation. Like Esther! Waves of anger swept over her. The cowards! They wanted what others wanted, and hadn’t the courage to take it. They did not do these things naturally, gloriously; they did them because the temptation had been too strong for them to resist. Weaklings, all of them!

She moved nearer to him; he put his arms round her suddenly and kissed her. She kissed him triumphantly and angrily. Oh, you good man! she thought. Oh, you good, good man! How amusing to think of you here, kissing your wife’s convict maid while she sleeps in the next room!

She struggled free. She saw that his face was pale pink; he looked comical kneeling there, with those arms, from which she had just escaped, hanging at his sides.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

“You must forgive me.”

She regarded his downcast head. Mt. Masterman, the master! And she thought then of how he had come aboard, and how she had tried to will him to look at her, and how she had appealed to him with her eyes. The master! He was no longer that.

“It does not matter,” she said.

“It is of no importance.”

“It is of the greatest importance,” he insisted.

“I am afraid that you will think I wished to insult you.”

Inwardly she laughed. He was not grownup at all. He might be Mr. Masterman, a power in the colony, but he was also a young man embarking on his first passionate love affair.

She shrugged her shoulders and stood up.

“One gets used to that… insults, I mean. You are sorry. I know.”

He was standing beside her. and Madam’s blue velvet dinner gown was a carpet beneath their feet.

“I must explain.” he said.

“You have disturbed me for a long time.”

She opened her eyes very wide.

“I… disturbed you?”

“You do not understand. The fault is entirely mine. It is nothing you have done, except to be so beautiful and so young and so different from other people.”

In spite of herself she felt a tenderness for him.

He went on: “Many times I have wanted to do that… many times before.”

“Oh, but…”

“It is wrong of course, very wrong. But I have told you now. and in future…” She watched him closely now; he was uneasy. There is so much unpleasantness here in this place. I would not wish anyone who comes under my authority to suffer from that.”

He walked over to the mirror; he stood there, facing it, looking into it but not seeing himself. Seeing her perhaps, with his wife’s dress half over her head.

Therefore,” he said, in the judicial voice with which he must surely address his committee meetings, “I want you to accept my apology. I must make you believe it will not happen again.”

He walked slowly to the door.

She folded the dresses and put them back. The pain of her discovery about Esther and Marcus was less acute. She went back to the kitchen, and she tried to think of Mr. Masterman, that cold, stern man, who, kneeling on his wife’s blue dinner dress, had humbly asked her to forgive him. She was cold to Margery, she was distant to Esther.

Esther tried to catch her hand once, but she made her own go limp, and she saw the look of pain and fear cross Esther’s face.

James came in. Carolan was wanted in the mistress’s room.

“Oh, Carolan. I have such a headache! Give me one of my powders. The master has been in; he is going away for some days, he says. To one of the stations. He says it is time he looked in on the men.”

Carolan thought. Days of it, days of monotony; and it will go on like this for years … seven perhaps. Men grew out of desire. Marcus had. Everard had. I am so tired of being a servant and listening to her wearying talk.

“When does he go, M’am?”

“Early tomorrow morning. He will be up by sunrise; it’s a good day’s ride out to the station. He is so energetic!”

“You look very fatigued, M’am.”

“Fatigued!” She closed her eyes.

“I am worn out.”

“It will be dark at any moment now, M’am,” said Carolan. It was still light, and she had never got over the wonder of the sudden descent of darkness, the absence of the English twilight hour.

“Shall I light the candles?”

“My powder first.”

“Oh, yes… I should rest all day tomorrow, M’am… with the master away. I have rarely seen you look so fatigued.”

“Give me my mirror.”

Carolan sat on the bed and held out the mirror. Oh, to recline on such a soft bed. How she hated the dampness of the basement! How she hated this life of a convict servant! So monotonous, and she should be grateful for its monotony when others, less fortunate, must endure horrors. Nothing to look forward to. She could still feel the imprint of that kiss on her lips. The master! The desire in his eyes had made them like Marcus’s eyes. I am so tired of being a servant; so tired of being unloved. My mother had had lovers when she was my age. My grandmother … It is not natural for the women of our family to go unloved.

Her heart began to hammer inside her; she thought it would burst. She was hardly thinking of Marcus at all now.

“I must get you your medicine,” she said. And she went to the drawer and unlocked it. She took out the bottle and shook it.

Lucille watched her with startled eyes.

“I said the powder.”

“Oh, yes, the powder. I thought, as you looked so tired… But as you say, it is just a headache. The powder.”

“No, no, Carolan. Give me that… I will have that. I never felt so tired in all my life, and what Doctor Martin said was that I needed to sleep more than anything.”

Lucille drained the glass.

“I will wash it; then I will draw the curtains, shall I? And I will leave you to sleep.”

“I do not know what I should do without you, Carolan!”

Carolan locked the bottle in the drawer, washed the glass, smoothed her mistress’s bed, drew the curtains.

“Sleep well, M’am.”

Lucille nodded drowsily.

In the toilet-room Carolan lit a candle. She held it high and looked at her face in the mirror. Her lips were parted, her eyes brilliant, recklessness was in her face.

I am so tired of being a servant!

Deliberately she went across the room and knocked at the door.

“Come in,” he said. She went in. Two candles burned on the mantel shelf. She blew hers out.

“I hear you are going away early tomorrow morning. I thought there might be something I could pack for you.”

She leaned against the door.

He said: “Pack? No. I do not think so. Pack? There is nothing to pack…”

“I see. Goodnight.”

Her voice was a breathless whisper.

He said: “Goodnight!” very steadily, and then: “Carolan!”

He was standing before her, looking down at her.

“You should not have come,” he said breathlessly.

“No,” she answered, “I should not. But tomorrow you are going away… I will leave you now. I thought…”

But he would not let her leave him now. He lifted her up; she put her arms round his neck. She was not sure whether this was her revenge on Marcus, or whether she had been unloved too long.

“Carolan,” he said, as they lay on his bed, ‘what are you thinking?”

“Of you… and of myself.”

“What of us?”

“It was wonderful, was it not?”

“It was wonderful.”

“You look exalted … and damned. Such a queer mixture!”

“You say such things! Adultery is one of the mortal sins.”

“It is a great tragedy, my coming here.” She put her arms round his neck.

“If you could go back, back to where I came in with the candle, would you tell me to go?”

“I believe I would commit any sin rather than not have had that.” She smiled, but he could not see the smile, for her face was pressed against his. She was thinking of Esther in her passion for Marcus, as reckless as this man, denying her God with the ease that he denied his. Esther and Masterman. Herself and Marcus. That was how it should have been. Yet it was as though life had carelessly shuffled them like cards in a pack, and then had turned up herself with this man. Esther and Marcus, in the wrong places.

She stroked the fine hair on his hands. There was the glimmer of a scheme in her mind. She was not sure what it was; she was not even sure that it was a scheme.

It was amusing to see anxiety breaking through his ecstasy.

“What a brute I am! You … so young and innocent … To think that I… I have always wanted to do the honourable thing by the people who came into my house …”

She laid her lips gently against his. Like her mother and her grandmother and her great-grandmother, she had the arts of loving at her fingertips.

“If I tell you something, promise not to despise me… Gunnar.

It is such a queer name!” His arms tightened about her.

“I like to hear you say it. My mother gave it to me. She was Swedish.”