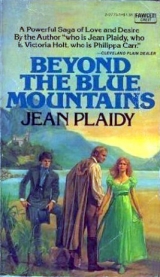

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“Carolan! Carolan! Oh, my sweet Carolan!”

“Here!” he cried.

“Wine to wash it down! We will both drink. Here, Carolan. To the future! To our future!”

The wine did strange things to her; made her light-headed. The room swam round and Marcus … Marcus, only was the one steady thing in a topsy-turvy world. She clutched his arm, half laughing, half crying.

“Marcus!” she said.

“Oh… Marcus!”

The door opened. There were Kitty and Millie and behind them, Esther. Carolan was ashamed that they should see her eating, with the glass of wine in her hand. She put down the glass unsteadily, and went to them.

“Why …” cried Kitty.

“It’s Marcus!”

Millie and Esther could only stare at the food.

“Come along!” cried Marcus.

“Sit down. We won’t waste time on formal greetings; we’ll talk as we eat.”

There he sat at the head of the table, watching them all… smiling queerly.

Kitty recovered herself almost as soon as she had drunk her first glass of wine. The striking off of all save one set of irons had brought great relief to her; she began to see daylight after the long dark night of torment. Marcus was delightfully familiar. To sit here, eating and drinking, the guest of a charming man, was stimulating. She was still in Newgate, she was still a prisoner, but things had changed.

Esther felt she was in a dream which had begun with the coming of Carolan into her life. Anything that was wonderful might happen now she was sure of it. She tried to suppress the unsuppressible desire to eat too quickly and too much.

Millie settled down at the table more naturally than any of the others; Millie was an animal who had suddenly come upon a patch of fertile land where grew the food she needed to keep her alive.

“What I want to know,” said Kitty, ‘is why you, a prisoner, can entertain guests in this manner and with such food and wine in Newgate?”

That is what I have been explaining to Carolan. It is the power of money. I merely send out for the food, and the turnkeys are paid well for their trouble in bringing it in.”

“I always thought you were a wonderful man, Marcus. I always I knew you weren’t what you said. You were always too distinguished to be an inhabitant of Grape Street!”

Too distinguished to be anything but a thief in fact.” he said.

Tell me,” said Carolan.

“Did you set my father up as a receiver of stolen goods?”

“I did. I must tell you both that he was very reluctant to enter into such a life. It was only starvation that drove him to it… not starvation for himself, but for his wife.”

Kitty began to cry softly. Marcus leaned over and filled her glass.

“Do not cry. Mamma.” said Carolan.

“I cannot bear it. Let us forget the past.”

“I am to blame for bringing it up,” said Marcus.

“I am a fool as well as a rogue!”

“I could not bear it,” said Kitty, ‘that he should be dishonest. He had always seemed to me so … noble. And then to know that he … even though he did it for me, which I do not doubt…”

“He was noble,” said Marcus. There are two kinds of roguery -his and mine. He becomes what the law calls a criminal, for the sake of his family; I, for the sake of___myself! Always remember that. This is a cruel world in which we live. For some it is impossible to live, impossible to eat. Those men have a right to have a family, but what can they do? What can they do? There is stealing and stealing. There are criminals and criminals. A society which is indifferent to so many of its members should not feel outraged if those of its members are indifferent to it. That is my law of life. It is wrong. I am wicked. But that is what I think. So, I cheat, I steal. And when I come to Newgate I see to it that I enjoy as much comfort as it is possible to enjoy; and I see that I entertain my friends.”

Carolan said: “I agree, I think. I am not quite sure, but I think I do.”

Esther spoke then for the first time. She lifted her head, and her blue eyes were brilliantly beautiful in her poor emaciated face.

“It is written “Thou shall not steal.” Therefore, whatever the provocation, it is wrong to steal.”

Marcus looked at her, and the colour rushed into her cheeks, and showed momentarily the beauty which health would have put into her face.

“Ah! You are an idealist, Miss Esther; I am but common clay. I adjust myself to the world in which I live; you dream of a society which could never be… at any rate not in our time.”

“It might be, were we all of the same mind,” said Esther.

“Esther,” said Carolan, ‘is a saint. Not all of us have her way of thinking. No, Esther, Marcus is right in a way. I did not think so until I came here, but here I have learned to think differently. A society which can tolerate this vile place…”

“People know little of it.” protested Esther.

“Did we know before we came?”

“Ignorance is no excuse. And come, can we say we had never heard of Newgate? We had, and we chose not to think of it; it was unpleasant. So we went on living our pleasant lives, and it is because of out indifference and the indifference of thousands like us that it exists. And so… innocent people, such as you and Mamma and Millie and I, can be forced to come here, to starve here, to freeze here, and perhaps to die here. We, the innocent, must suffer because we are poor and friendless, while the real criminal…”

Marcus bowed his head ironically.

“I’ll finish, Carolan. A real criminal can buy the best Newgate has to offer. That’s true! Life is a wicked old strumpet; she’s devishly sly and mercenary; but laugh with her and she’ll laugh with you. Even in Newgate, laugh at her and she likes it!”

“Your words hurt Esther,” said Carolan.

“I am sorry, Esther.” His eyes, Carolan noted, were almost caressing as they rested on the girl.

“But it is necessary always to face facts. Where shall we be if we do not? The answer is obvious… in Newgate most likely without a penny piece to buy a bit of extra bread. Carolan agrees with me. Carolan. I think you and I are of the same mind on lots of subjects. The thought warms me. You and I…”

Carolan broke in impatiently: “We are certainly not of the same mind! Do you think I admired your way of life? You are a thief You are … It is that people should be sent to this vile place before they have been found guilty …” She broke off angrily.

“Oh How I hate that creature, Crew.”

“Do not hate him. Carolan. He was following his trade. He probably relies on what he gets by these activities of his. I doubt whether he enjoyed the whole of the forty pounds he got for betraying an escaped convict; or even what he picked up on account of you and your mother and Millie. And he worked very hard for his reward and his Tyburn ticket.”

“You would make excuses for him!”

“For him and for us all.” said Marcus.

“Absurd!”

“Doubtless.”

“You wish. I think to be contrary. You excuse a man who has brought Mamma… to that!”

Tears filled her eyes; all the blazing indignation had left her; there was only hopelessness in her now.

“Carolan!” he said tenderly.

“Carolan…” The door was pushed open slowly, and a tousled head appeared. It belonged to a black-haired, black-eyed young woman with large gilt earrings swinging in her ears, and a red silk blouse stretched tightly across her full bosom. She raised heavy black brows, and surveyed them.

“Hello. Will.” she said in a drawling voice.

“Is it company then?”

“Rather an unnecessary question, Lucy, since I have always been led to believe you have a very sharp pair of eyes!”

His voice,was silky with suppressed anger; hers was rough with it. Instinctively Carolan guessed at the relationship between them.

“Well,” said Lucy, “I was never one to intrude. I will say goodnight!”

“Goodnight, Lucy.”

The door slammed.

Carolan met Marcus’s eyes; he smiled briefly.

“A friend of mine,” he said.

“In for passing counterfeit coin.”

“Obviously a monied friend,” said Carolan.

“Like you, she seems to enjoy her freedom!”

“She seemed angry with us,” said Esther.

“She seemed as if she knew we came from the Common Side.”

Carolan smiled tenderly at Esther. How innocent she was. It would not occur to her that this Marcus, who had been so kind to them, was a rake, a philanderer, a libertine. Poor Esther! Her upbringing had been such that the bad and the good were divided into two distinct lots all bad and all good. Esther had much to learn.

“I do not think I liked her very much,” said Kitty. Kitty had drunk a little too freely of the wine; she felt pleasantly drowsy. She leaned her head on her hands and closed her eyes. Esther had drunk but little of the wine, but she too was sleepy. Carolan felt wide-awake, excited by the change in her circumstances, by the presence of Marcus who now. more than ever he had. aroused in her mixed emotions.

He twirled the wine in his glass and leaned towards her suddenly.

He said: “Come, Carolan! Out with it! You are thinking with great disapproval of my friend, Lucy, are you not?”

“Why should I?”

“I do not know why. Carolan; I only know you do.”

“I cannot see why I should concern myself with your friends.”

“Darling Carolan,” he whispered, ‘you were so angry; you flew to such conclusion that you made hope soar in my wicked breast.”

“You talk in riddles.”

He caught her wrist; his fingers were warm. She looked down at them; his hands had always attracted her, the hands that picked pockets so deftly, that were his stock in trade.

“No, Carolan. We understand each other well enough. We might understand each other better. Carolan, it will grieve me very much to think of you and your mother and friend Esther, and poor Millie, going back to the foul felons’ side.”

She shuddered.

“Do not let us think of it. It has been a great treat for us to taste real food again, to eat it in comfort.”

“Were you very angry about Lucy?”

“Angry?”

“Sparks flew from your eyes.”

“Ridiculous! How could they?”

“A figure of speech, of course. But I saw all sorts of things in your eyes. I myself was angry with her for coming in like that; and then I was glad she did.”

“You are very imaginative.”

“No … merely observant. See how your mother sleeps. And poor little Esther, she is nodding too. What a difference one meal has made to them! Perhaps, too, it is the quiet of this room. What say you?”

“I am frightened for my mother; she is brighter now, but there is a terrible change in her.”

“I will be frank with you, Carolan, because, although I am a fool and a rogue, I have enough sense to know that one must always be frank with you. Lucy was my friend … a great friend. She is a generous soul, and life has dealt cruelly with her as it has with us. We helped to give each other a few home comforts here in Newgate… do you understand?”

“Of course. But is it necessary to explain this to me?”

“It is very necessary. Carolan, from the moment I first saw you I knew there was something different about you.”

“So you stole my handkerchief! There was not much else since I had already lost my purse. You must have been very disappointed.”

“How you fly into a passion, my dear! Look!” He put his hand inside his jacket and produced the handkerchief.

“I carry it always.”

“Why?”

“Surely you know.”

“Sentiment? You should never let sentiment stand in the way of common sense, and does it not show a lack of common sense to carry a worthless handkerchief about with you?”

“You are quick! Do you hate me, Carolan?”

“How absurd! Of course not.”

“Then since you cannot hate me, perhaps you could love me.”

“I think this is an absurd conversation which does not lead us anywhere. Look at that poor child Esther!”

“Poor child Esther! She is not strong, and yet doubtless before she came to this place she was well enough. Newgate gnaws the strength out of a man or woman.”

“Unless he knows how to live there!”

“Wise Carolan. Do you know?”

“I do not understand you.”

His grip on her wrist tightened.

“Stay with me,” he said.

“Stay with me here. No! Do not fly into another passion. Listen! Be wise. I will strike a bargain with you. Stay here with me, live in as much comfort as money will buy in Newgate. Your mother, your friend Esther and poor Millie shall have a room like this one; food shall be sent in to them. And you… share this with me.”

She leaped to her feet, her cheeks flaming red.

“Do you think I am one of your Lucys?.”

“No! Assuredly I do not.”

“Have you forgotten that I am to be married in a short while?”

“You will not marry your parson, Carolan.”

“I think it is time we left you. I .think it is a pity we ever accepted your hospitality.”

“Listen! How will he know what is happening to you? If it were possible to get a message to him, then he might know, but whether he came for you would be another matter. Money would send that message, Carolan. Suppose I held that out as a further inducement?”

“You are vile!”

“I am, alas. And you are very desirable, which makes me my vile self.”

“Mamma!” cried Carolan.

“Esther! It is time we went.” She nodded towards Millie, who had been watching them with bright, unintelligent eyes.

“Wake them,” said Carolan.

“We must go now.”

“Remember the misery of the felons’ side. Carolan,” whispered Marcus.

“Remember it! I shall never forget it as long as I live.”

“And you will go back to it!”

“Assuredly I will go back to it.”

“And allow them to go back to it?”

“They would not wish it otherwise that I know.”

“And do you hate me very much, Carolan?”

“Hate! That is too strong an emotion to waste upon such as you. Let us say that I despise you… that I never wish to see you again … And I heartily wish that I had never eaten your food!”

“It is easy to say that after the feast, Carolan. Would you have said it when you stood at my side and I fed you over my shoulder?”

“Oh, let me go!”

“You disappoint me. Carolan. You prefer that foul place and that foul company to this room and mine.”

“Yes,” she replied, “I do prefer it! Mammal Esther!” She shook them.

“It is time we went. Come along!”

Kitty opened her eyes.

“I dreamed,” she said, ‘that we were in a beautiful house in the country… Darrell and I, and you, Carolan …”

“Wake up now,” said Carolan.

“It is time we were back.”

“Carolan, must we go back to that frightful place? They won’t put those dreadful irons back, will they? This one pair is bad enough. They cut my skin. It frightens me, Carolan. You know how white my skin used to be …”

“Esther,” said Carolan, ‘help me with Mamma.”

Kitty got slowly to her feet; on either side of her stood Carolan and Esther. Millie kept to the background.

Kitty said, with sudden graciousness: Thank you, dear boy! It was a wonderful feast. I hope that some day we shall be in a position to invite you to dine with us.”

“You must come again,” said Marcus.

He was looking at Carolan, but she would not meet his eyes. He strode to the door; a turnkey came and conducted them back.

How dingy, how gloomy, how foul the place seemed after that brief respite! Bright eyes peered at them as they returned. What had happened to them? There was no sign of lashes received. Here they were, back again.

Kitty, refreshed and with new hope springing up, became a pale shadow of her talkative self. A group gathered round her;

she talked to them.

“We dined with a friend … a wealthy man. It was a wonderful meal… We shall go again, of course. It will not be long, I assure you, before we are out of here. We have friends, you know … it was all a mistake, our coming here …”

Carolan listened to her mother, and she was filled with fury against Marcus.

Esther said: “He was a charming man, a good man although he spoke so wildly. It is hard to be in such a place and refrain from bitter feelings. But he is a kind man. Do you know, I think it grieved him that he could not afford to take us all out of here and give us a room to ourselves.”

“You think that he wanted to do that?” said Carolan.

“Indeed I do!”

“Then if he wanted to, why did he not do so, do you think?”

“It was doubtless because he had not enough money to buy luxuries for us all.”

Millie was fast asleep. Kitty was still talking excitedly.

Esther’s voice was dreamy.

“I think I have never experienced such joy as when I took my first mouthful,” she said.

“I feel I would have given my life, if it had been asked, for one mouthful of roast chicken. And there was never such a roast chicken as that one! Did you note how brown and crisp was the outside, and the flesh melted in your mouth like rich butter!”

“You talk of your God,” said Carolan.

“It seems to me your belly is your God!”

Tears filled Esther’s eyes; Carolan turned away. Ought I, she was thinking, to have given them that room, food … real food … to eat every day? Do I set too high a value on myself? It is not too late perhaps … Her heart began to beat more rapidly, she put her hand over it; it seemed to be leaping up into her throat. He touched something in her, that man, rogue though she knew him to be. She loved Everard; she would wait all her life for Everard. But there was something in the man, Marcus, that moved her, that fascinated her, that tempted her now to say: “I will do it for their sakes.” and made her wonder whether, after all, she might not be doing it for her own.

It was a wicked passion, this racing of the pulses; something purely of the senses. When he had laid his hands on her she had liked that; she had been angry at the sight of Lucy and the knowledge of what her relationship was to Marcus. When he said her name over and over again “Carolan! Carolan!” with the vibrating note in his voice, she felt weak and wanton and very wicked, yet revelling in her wickedness. Everard had been shocked a little by her displays of affection.

“My dear Carolan… my dear… how fierce you are!” He had liked it and tried not to like it. Marcus would never try not to like any affection she had to give him; he would offer passion for passion.

I am really very wicked I thought Carolan, and remembered her mother’s procession of lovers. But she was different from her mother; her mother would have so willingly made the sacrifice for the sake of others just now … and would have been able to believe it was a sacrifice. Carolan must see the truth. She tried not to. She thought-How can I let them suffer here in this hell when there is escape for them! How can II And she fell to shivering.

Esther leaned over her.

“Are you well? Have you the ague… or fever? Why, you are hot and yet you are shivering!”

“I am all right!” snapped Carolan.

One of the turnkeys came in; he was jangling a bunch of keys, and grinning.

He said: “This way… the four of you. This way Carolan leaped to her feet.

“What do you mean? Where are you taking us?”

“Orders is orders,” said the turnkey, and there was a hint of respect in his voice, which was not lost on the listeners. Carolan saw looks of envy leap up in several faces. It was true, they were thinking; all that Kitty had told them was true; they were of the quality, these people! But most of all their envy was of Esther who had been chosen as their friend and was now sharing their good fortune. One woman sat down in a corner and wailed in her anguished jealousy like an animal in distress.

“Come on,” said the turnkey, still respectful.

“This way!”

They went along corridors and up staircases. They were shown into a room like the one where they had dined with Marcus. There was a bed in it … and rushes on the floor. It looked luxurious after the Common Side.

“Here you stay,” said the turnkey.

“Gentleman’s orders!”

He took a piece of paper from his pocket.

“Gentleman says I was to give you this,” he said, and handed it to Carolan.

She took it and read:

Of course I hoped you would submit to temptation. But you did not imagine that I would let you all stay in that place, did you? Come and dine with me tomorrow. Now you shall see what a good heart beats under my villainous exterior. Ask the turnkey for writing materials and write a note to your parson. He will see that it is dispatched.

William Henry.

Kitty said: “That is from Marcus?”

“William Henry, he calls himself now,” said Carolan. She added petulantly: “How can we be expected to get used to this continual change of names!”

“My dear, you sound quite cross; what has come over you? This is luxury. A bed! I declare I long to lie on it and rest my poor leg.”

“He says if I write a note it will be delivered … I am going to write to Everard.” She said to the turnkey: “Will you please bring me pen and paper?” The turnkey nodded and disappeared immediately.

“What a wonderful man he is!” said Kitty. She lay back on the bed.

“This is heaven! This is comfort! My poor leg… it is throbbing dreadfully.”

“I will ask for water to bathe it. and a bandage, Mamma. It seems that nothing is too much for these people to do for Marcus’s money!”

Esther looked at her strangely.

“You talk as though you hate him.”

“What! Hate our benefactor. Lie down on the bed, Esther. Enjoy the luxury; I shall when I have written my letter. Look Millie, if you lie along the foot, the rest of us can lie the other way. A bit of a tight squeeze, but what luck … a real bed. Esther, why do you not lie down? Why do you not try our new bed?”

“You look strange. Did you drink too much of your friend’s wine? There is a flush about your face. Carolan, are you all right?”

“I am quite all right. I am not tipsy either! Ah! Here come my pen and paper. Now hear me ask for water and a bandage. I can give orders now because I have a friend named William Henry … and he has money…”

It was some time before Carolan joined them on the bed. She had written to Everard; she and Esther had bathed and bandaged Kitty’s leg; Esther had knelt down by the bed and thanked her God for this newly acquired luxury. Carolan lay very still; she was cramped, and it was impossible to move without disturbing the others. Millie was snoring; Kitty was breathing deeply; Esther, Carolan believed, was awake.

“Esther!” she breathed.

“You do not sleep.”

Esther’s voice came to her in the darkness.

“It is the unaccustomed comfort. The bed is so soft… I am so used to hard planks.”

“Why do you cry, Esther?”

“Because it is so wonderful. Because I have prayed for something like this to happen.”

There was a silence, then Esther said: “He is very kind, your friend. He is a good man, though he tries so hard to pretend he is not.”

“He is a thief!” said Carolan.

“He is a rogue… Do not forget that. He was not brought to this place wrongfully.”

“But Carolan, you have said that no one should be brought to a place like this whatever their crime. You said it. Then he has been brought here wrongfully.”

“Hush!” said Carolan.

“You will wake the others.” She tried to sleep, but she could not. She lay there, cramped.

uneasy, thinking of Marcus.

It was stiflingly hot in the women’s quarters. When Carolan had stood at the top of the ladder and peered down into the darkness below, she had felt sick with hopelessness and terror. The women’s quarters consisted of double tiers of bunks roughly divided into berths; and sharing Carolan’s was her mother, Esther, a crippled girl of twelve and a middle-aged woman. The little girl had cried intermittently ever since they had come aboard; she refused to talk to anyone, and would hide her face in her hands, peering through her fingers, if spoken to, suspicious and defiant. The woman had been drunk all the time the ship lay at anchor; gin had been smuggled in for her; now the ship had set sail and she no longer had her gin, she was either quarrelsome or over-friendly. She sang lewd songs for hours at a stretch; and in close confinement with this woman, Carolan knew that she, her mother and Esther must spend the next months. Millie they had not seen since leaving Newgate. Her sentence had been the same as Carolan’s seven years transportation but she had been sent to another ship. Poor Millie! It was to be hoped she would not suffer too deeply. Carolan thought of her often, hating herself, for it seemed to her that never would she be able to forget that she had been the chief instrument in bringing trouble to these people.

But even in the depth of misery there is some comfort to be had. They were all together she, her mother and Esther and it might so easily have happened that they would be parted. She believed, though she was not altogether sure, that Marcus was aboard this ship. Marcus she had told him that never, never could she think of him as anyone but Marcus, to which he had replied characteristically: “What’s in a name? As long as you continue to think of me, what matters the label?” Marcus had been sentenced to transportation for life, Kitty for fourteen years, and Esther, like herself, to seven.

She would clench her hands and think of the mockery of the trial, the weariness of the court, its automatic and careless sentences. It is so much easier to say “Guilty!” than “Not Guilty!” And who is to care, save a poor prisoner of no significance whatever?

Always there would stand out in her memory the ride to Portsmouth. Chained, dirty not Carolan Haredon surely, this creature, whose red hair, once so sleek and shining, was matted and filthy! Carolan, who had danced in a green dress at her first ball, now a grotesque scarecrow, her thin body hung about with rags. The van had been open and crowds in the street had watched its progress. They laughed; they pointed; they jeered at the van’s most miserable cargo.

She had prayed then she who had vowed never to pray again.

“Let me die. This I cannot endure.” Then someone had thrown a rotten apple at her and she had stopped praying, for furious anger had surged up within her. She had seized the apple and flung it back into the crowd, which action had been greeted with roars of ribald laughter; and then rotten fruit, mud, dung came thick and fast.

“I’ll never forget it, she thought; and indeed the very memory of it set her heart pounding with fury.

In Portsmouth jail with its Gentlemen’s Side and its Common Side in fair imitation of its big sister, Newgate they had dined with Marcus. His eyes had glittered with excitement because the last days of prison life had been lived through. There was the weary waiting before they set sail, there was the dreaded journey across the sea to the other side of the world, but the filthy Newgate days were over, and that in itself was a matter for rejoicing.

Marcus had said: “My darling, how it grieved me that you should travel down as you did! Believe me, I tried to move heaven and earth to get you with me in a closed carriage. There are some things that money cannot achieve please understand that that was one of them.”

She tried to tell him of that journey, but the words choked her, and she spoke only one sentence to sum the whole thing up: “I wished I was dead.”

“Carolan, my sweet,” he said, ‘never wish that. That is an admission that life has defeated you. Why long for death when you know not what it brings! Eternal sleep? Do you want it, Carolan? That sort of death is not for us, Carolan, and the only sort of life we know is the hard life and would such as we are want it soft? Would it not lose its zest?”

“Esther has beautiful ideas of death,” she said. And they had both looked at her. There was an unearthly beauty about the girl; her spiritual strength shone in her eyes for her belief was invulnerable.

“But Esther, how can you be sure?” demanded Carolan, irritated.

“How can you be not sure,” asked Esther, ‘when you know?”

“You do not know!” said Carolan, impatient.

“Who has ever told you? Your father? Your mother? But what did they know?”

“They knew.” said Esther.

“I could not bear not to believe.”

“It is comforting, doubtless,” said Carolan. Marcus put his hands on her shoulders.

“But Carolan, do we want comfort? I do not think so: not unless we know it to be truth. We cannot accept things because they are comfortable. Why, Dammed, our forefathers doubtless thought it was comfortable enough living in their uncivilized way. It is the uncomfortable things which make the world progress.”

Esther shook her head.

“I wish I could make you see it as I do.”

“Ah, Esther!” said Marcus.

“We are neither of us saints, Carolan and II” “No,” said Carolan, ‘we are sinners … angry sinners. We cannot accept cruelty because God decided that we should. No, we will fight against God; we will fight for ourselves!”

Marcus laughed. How his eyes glittered! She thought. He is already contemplating escape when he gets to Botany Bay. And she warmed towards him; they were much of a kind, he and she. Everard was of a kind with Esther. Everard was ever constant in her mind. Everard who had not come for her, who had accepted cruelty as God’s will. Perhaps he had wanted to come; she imagined his mother’s begging him not to … and Everard’s fighting with himself. Everard the parson. Everard the lover. She had always suspected the parson of being the stronger of the two. Perhaps that was why she had suffered so deeply in the van which had taken her to Portsmouth, for then she had known that Everard was not coming; that was why. in the open van on the Portsmouth Road, she had despaired.

And when she had thrown that rotten apple back into the crowd, she had been throwing it at Everard and Everard’s mother. Had she been unshackled, she would have leapt from the van and fought them with her hands. She was not the sort to suffer in silence, to pine away and die; she was the sort to fight, to hurt herself, to hate… “I wish I were dead.” she said again, remembering.

And then there had been the comfort of seeing Marcus in the Portsmouth jail. That jauntiness of him, that glitter in his eyes! Rogue, thief, philanderer that he was he was more her sort than gentle Everard.

One pain will subdue another. There was poor Mamma getting weaker and weaker, and thinking of Mamma it was possible to forget Everard a little.

The last weeks had changed Kitty beyond recognition. She was like a flower that has been cherished in a hothouse, and is thrown onto a dung heap. No flower could be expected to last long in that condition. When they had come on board and had stayed on deck while farewells were said, Kitty had sat propped up against the rail unable to move. Her face was a greenish colour, her eyes bloodshot, her tongue thickly coated, and her lips twice their usual size. She was, Carolan knew, unaware of her situation, which was perhaps not a matter for regret in itself.