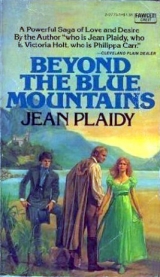

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“I’d like to do it for you, Harriet.”

“Well, George! Well!”

Coy as a schoolgirl, and immensely gratified! He felt suddenly flat.

“I’ll be getting along, Harriet. I’ll send Jennifer in to meet the girl’ She stood at the door, watching him go striding out to his waiting carriage. Why, she wondered, had he not spoken? She had been sure he was going to.

Leave-taking was difficult. They sat side by side in the coach now, their hands touching.

Darrell whispered: “I shall be thinking of you every minute until I see you again.”

“And that will be soon,” she answered.

He knew her aunt’s house. It stood back from the road, and near it was a little wood; if she came out of her aunt’s house and turned right she would see the wood. It would shelter them for their first meeting, and .that should be tomorrow evening at eight o’clock. It would be better to wait for evening. He would come to her on his uncle’s chestnut mare, and wait for her just inside the wood; he would tell her what his Uncle Gregory had said about their marrying, because that was a matter he would discuss with him at the earliest possible moment.

“It is not real parting,” said Kitty, and smiled up at his clear-cut, handsome face and rather delicate features.

The coach rumbled on. The merchant and the matron were discussing Exeter, and every occupant of the coach was excited because they were nearing the end of the long journey. Under cover of such conversation it was possible to exchange vows of eternal affection.

“I thought you were wonderful, when I first saw you. I could just see your mouth; your hat hid the rest of your face.” She laughed softly and pressed closer to him.

“You stared so!”

“How could I help that?” he murmured.

“And Kitty … now I have got to know you I’ve learned that you are more wonderful than I ever thought anyone could be.”

He kissed her ear, and they laughed and laughed round the coach. Had anyone seen? Who cared if they had.

The coach rumbled into Exeter and pulled up in the inn yard. The door was flung open.

“Perhaps,” whispered Kitty, “I had better not introduce you to-my aunt… yet. Perhaps it would be better to wait a while and see…”

There was bustling to and fro whilst the luggage was unloaded. Kitty stood with her bags beside her, looking around her for Aunt Harriet.

A woman was coming towards her a small woman in a dark cloak and hood. She stood before her; she had sharp, darting black eyes.

“Are you Miss Kitty Kennedy, who is on her way to Miss Ramsdale?”

“Why, yes. Are you… my Aunt Harriet?”

Laughter shook the thin shoulders momentarily.

“No. But I have come to meet you. I have a carriage here to take you to your aunt’s house.” She looked round and beckoned; a man came and picked up Kitty’s bags.

Kitty turned and smiled at Darrell who had stood by, watching. His face looked bleak, she thought, but there was no time to ponder on that, for her companion was hurrying her into a carriage.

The door slammed. The woman sat back, studying Kitty, and Kitty studied her.

She had thrown back the hood of her cape and disclosed dark, rather frizzy hair; her brows were dusky, her dark eyes large yet alert. Kitty felt them taking in every detail of her appearance. She wondered if she were a servant of her Aunt Harriet’s; her manner was a little arrogant, hardly that of a servant.

The carriage rolled out of the yard.

“Do tell me your name,” said Kitty.

“Jennifer Jay.”

“And my aunt…”

“I have come to meet you on Squire Haredon’s behalf.” She stopped, watching the colour flood into the girl’s face.

“But,” stammered Kitty, ‘why? I was going to my Aunt Harriet…”

“So you are. But Squire Haredon thought it would be helpful … to your aunt… to send his carriage.”

“I see. He is very friendly with my aunt?”

A scornful smile twisted the woman’s mouth.

“He has known her for a number of years.” Jennifer leaned forward.

“I expect you are very like your mother.”

“I am supposed to be. You knew my mother?”

“Hardly! She left this place years ago, did she not? I am twenty-one. Besides, I did not live here as a child.”

“It was good of Squire Haredon to send his carriage.”

“He is a generous man… at times,” said Jennifer.

Yes, she was thinking, why had he gone to all this trouble for Harriet Ramsdale? She wanted to marry him, the sly old virgin! And she thought no one knew it. She, Jennifer, knew it; even those half-witted sluts, who worked for her, knew it. The squire knew it; there were times when she could almost get him to laugh with her over it. There were times when it was possible to get almost anything out of the squire. But he was hot tempered; the last time she had mentioned Harriet’s name he had shut her up roughly; she had thought he was going to strike her. It wouldn’t have been the first time, brute that he was, Like a great bull sometimes, rushing at you angrily … and then getting amorous. A smile lifted the side of her mouth.

And now this niece. Disdainful beauty! He would surely be impressed, but he wasn’t the sort to press where he wasn’t wanted. And who was the young man with the girl when she had got out of the coach, looking at her with those dove’s eyes? This was going to be exciting, if a little dangerous.

It might be a good idea to find out all she could. Knowledge usually came in useful. She had a sharp tongue it was one of the things which amused the squire. It was an easy matter to get into his bed; any kitchenmaid could do that; the art lay in staying there.

“You had a pleasant journey?” she asked conversationally.

“Good companions?”

“Very.”

“I thought one of the young men who got out of the coach looked as if he might be a charming travelling companion.” How easy it was to make her blush.

Did you?”

“Yes. I thought he had specially friendly glances for you.”

“I think,” said Kitty slowly, ‘that you must be referring to Mt. Grey. His uncle, he was telling us, lives in Exeter.”

“Mr. Grey … I do not know him. You see, I came here only four years ago. I don’t know Mr. Grey, but as I said, he is a personable young man and, I should think, a pleasant travelling companion.”

She would garnish the story of this journey she would tell the squire with a description of the flushing young woman who had perhaps been a little indiscreet with a handsome Mr. Grey. She could always make Haredon laugh, and when she made him laugh she was the mistress of the situation … always. She even thought at such times that he really was imagining her at his table, entertaining his guests; after all, it would soon be forgotten that she had come to his house as governess to his children and had been his mistress before she became Ms wife.

Kitty said quickly, to turn the conversation from Darrell: “And you… you are a friend of Squire Haredon’s?”

Jennifer’s head tilted proudly.

“I am in charge of his children.”

“That must be interesting. Tell me about the children.”

“There are two of them. Margaret is nearly two years old; Charles is five.”

Kitty smiled encouragingly. It was more pleasant to think of the squire as a family man.

“I am fond of children; and you must be too. since you have chosen the task of taking care of them.”

“I did not choose it it was thrust upon me. I was at a school for young ladies when my father died suddenly. It was a shock to me to learn that I was penniless. There was nothing to do but earn my living it had not been intended that I should so I acquired this post! Margaret was not born then.” Her eyes were sly, Kitty thought, and wondered what made them so. Jennifer was thinking of her arrival at Haredon, and of the interest she had aroused in the squire right from the beginning; hotly pursuing in those days; quite gallant; now he blew hot and cold. She had been sorry for poor Amelia, but that had not stopped her from thinking of Amelia’s husband. Amusing! Great fun. keeping him at bay! He could be so angry when frustrated; he had no finesse, the great bull! But when Amelia had died that had seemed like fate. Good God, she needed luck. He would marry again. Weakly, but with an element of cunning, she gave in to him; she had thought that was the way. Perhaps it was; she wasn’t sure. She had that in her which could enslave a man … up to a point. She looked at the girl opposite with faint contempt. She was too sure of her beauty, that girl, to think of much else, and beauty was not all-sufficient; wit came into it; the power to make a man laugh, to find the vulnerable spot. Cleverness was every bit as important as beauty. When she thought of that she was stimulated.

“Oh…” said Kitty, ‘the squire’s wife…”

“She is dead.”

Now why did her eyes cloud suddenly like that, as though she were sorry Amelia had died? Soft, this girl! But those eyes, that skin and that mouth, He must be interested, if only momentarily. I “It was after the birth of Margaret; she went to be churched. It was in November, and November can be a damp, unhealthy month in this part of the world.”

“Poor lady!” said Kitty.

“And poor little children!”

“They are well looked after,” said Jennifer almost tartly, and then the secret smile twisted her lips. And so is the squire, she said to herself. I “You know my aunt?” asked Kitty.

Jennifer tossed her head.

“I have not visited her,” she said with scorn.

“A governess does not visit the gentry.”

The carriage rolled on. Kitty closed her eyes: she was not looking at the immediate future; she was looking beyond, to marriage with Darrell.

“You are doubtless tired,” said Jennifer.

“Close your eyes and doze a little.”

Kitty smiled and kept her eyes closed: it removed the necessity of talking to Jennifer, for which she was rather pleased. There was something about the little woman, strange and unfathomable, that was almost anger, and Kitty never had any real desire to fathom. She thought of Darrell, of the fine down on his cheeks and the sudden hard pressure of his mouth on hers.

Harriet heard the carriage draw up, and went out to receive her niece.

She gasped at the sight of Kitty. A young woman, a sophisticated London young woman with clothes that were much too fine for the country, who appeared so startlingly like Bess that she felt the resentment she had always felt towards her pretty sister surging up in her. And with her, that creature from Haredon, looking demure enough in her sober cape; but whenever Harriet saw her she could not shut out of her mind the stories she had heard; imagination could be a mocking enemy ill forced pictures into your mind, and though you tried to ignore them and make your mind a blank, the pictures remained.

Kitty stepped out of the carriage, and the coachman brought in her baggage.

Most definitely, decided Harriet, that creature should not be asked in to drink a glass of cowslip wine. It was really very thoughtless of George to send her to meet a niece of Harriet Ramsdale. If the stories one heard of this woman were true, it was a wicked thing for George to have sent her. Unchastity in George himself was forgivable, because God had made men unchaste creatures; but the women, without whom of course the unchastity of men could not have been, were pariahs, to be despised, to be turned from, to be left to suffer the results of unbridled sin and wickedness. She hated to think of it; she would rather think of her cool still-room or garden laid out with her own hands. But when she was near women such as this one. pictures forced themselves into her mind and would not be ousted.

“Kitty!” she said, and took the girl’s hand. Bess’s eyes and Bess’s mouth! Her skin was flushed and her dress was too low-cut and revealing. Harriet thought uneasily: Is this going to be Bess all over again?

She said: “I have a meal waiting for you.” Then she looked through the carriage window.

“I shall convey my thanks to the squire.” Jennifer’s head was tilted higher and her eyes were really insolent. The first thing Harriet would do, if she married the squire, would be to dismiss that girl.

As Harriet led her through the door to the cool hall, Kitty heard a movement on the stairs, and saw two young excited faces peering down at her. She took off her hat and put it on the oak chest there. Harriet looked at it could not stop looking at it. It was such a ridiculous hat and, lying there, it spoiled the order of the orderly house.

“I do not like litter, my dear. Take up your hat; you can hang it in a cupboard I have cleared in your room.”

Kitty felt chilled by the neatness all around her. Tears suddenly stung her eyelids, and she thought of her mother’s apartment with the cosmetics arrayed before her mirror, and the trail of powder across her dressing-table, and the fluffy garments flung down anywhere. Oh, to be back there! But then she would not have met Darrell, and loving and being loved by Darrell was going to be glorious. She smiled dazzlingly. Harriet was a little shocked by the smile; it expressed such confidence in life, and she, a good and virtuous woman whose future was secure, had never felt that confidence. Bess had had it though; here was Bess all over again.

“Come and eat,” she said.

Everything was spotlessly clean. There was cold mutton on the table and fruit pie. Kitty put her hat on her head, since there seemed nowhere else to put it, and sat down at the table.

“Peg.” called Harriet.

“Bring a glass of ale.”

“Peg?” said Kitty.

“Who is Peg?”

“My maid. A lazy, good-for-nothing piece if ever there was one. And the same applies to Dolly, my other maid. I hope you have brought some recipes from London.”

“Recipes?” Kitty found that so funny that she began to laugh, and because tears had been so neat it wasn’t possible to stop laughing. Peg came in and stared at the newcomer, then she began to laugh.

“Please, please!” cried Harriet.

“I do not… I will not…” But they went on laughing, and Dolly came and peeped round the door.

Harriet’s face was full of anger. Kitty saw this, and stopped.

“I am sorry. It was just the thought of my mother jam-making. She never did, you know; she never thought of things like that. If she wanted jam she just got it out of a pot; she would never think of how it got there.”

Peg and Dolly were staring in frank amazement at this young lady from another world. Dolly was even so bold as to come close and touch the stuff of her dress.

“Dolly. Peg! Leave this room at once,” ordered Harriet, ‘and don’t dare enter it until I send for you, unless you wish to feel the whip about your shoulders.”

When they had gone, Kitty said: “I am sorry. I expect that was my fault only the thought of my mother making jam was so runny.”

“You are evidently amused very easily!”

Kitty began to eat. Poor old Aunt Harriet, she thought; she didn’t look as if she had a very happy time. It must be wearying living in this place, with only recipes and clean floors to think of. How gloomy the prospect, if she had not met Darrell. But, of course, meeting Darrell had changed everything. Perhaps, if she hadn’t met him, she wouldn’t be saying poor Aunt Harriet, but would just be disliking her. You couldn’t dislike anyone when you were in love; you were only sorry for people like Aunt Harriet.

She ate the fruit pie and drank the ale. and all the time Aunt Harriet talked. She talked of what she would expect Kitty to do; there was the garden; there was the house, so many tasks to be performed, as Kitty could imagine, and it was Aunt Harriet’s pride and joy to keep her house clean and shining, and her garden beautiful. Was Kitty fond of fine needlework? No? That could be improved. Did she play the spinet? Dear! Dear! Her education had been neglected. Aunt Harriet confessed that she had been prepared for that, and she added, almost indulgently, she was not sure that she would not rather work on virgin soil.

Kitty watched a harassed bee buzzing and banging himself ineffectually against the windowpane. Her thoughts were on the bee, not on what Aunt Harriet was saying. And from the bee they went to Darrell… A whole day to be lived through before she saw him. She wondered how she would slip out of the house; she had an idea that Aunt Harriet would be a watchful person, not easy to deceive. The thought stimulated her rather than anything else. Perhaps she would run away with Darrell. She was sure Aunt Harriet was the sort of person who would never approve of their marriage.

“If you would care to see your room,” Aunt Harriet was saying, “I will show it to you. You could unpack your things and then come down and take a walk in the garden. I could show you what I hope you will make your duties there. What a lovely thing is a garden! Do you not think so? I always consider it a privilege to be allowed to work in my garden…”

They went up the stairs: everything smelt of soap.

“Your room!” said Aunt Harriet. It was a pleasant enough room, rather bare it seemed after her room in her mother’s apartment, but good since it was to be hers, and she would enjoy privacy in it.

“I shall expect you to keep it clean yourself. I cannot lay extra burdens on the shoulders of those two stupid girls. Heaven knows they drive me to distraction now with their follies.”

Kitty unlocked her trunk. Aunt Harriet was kneeling beside it, thrusting her hands into the folds of gowns and mantles.

“What elegance!” She was both grim and prim.

“You will not have need of it here in the country. We can alter these things though; are you handy with your needle?” She made a little clicking noise with her tongue.

“Your mother was most unsuited for motherhood; it seems she neglected you badly.”

“She never did!” cried Kitty in revolt.

“I loved being with her. She was a lovely person. She was the best mother in the world!” Her hands were buried beneath silk and fine merino. She took out the miniature and looked into the lovely, laughing face portrayed there. Harriet, full of curiosity she could not understand, peered over her shoulder and gazed at the magnificent bosom and the bare white shoulders.

“It was done,” said Kitty, ‘by an artist who loved her.” Harriet drew a sharp breath, and the jealousy she had felt for Bess was there in that room as strong as it had been twenty years before.

“It is … immodest! A man who … loved her! Oh! I can well imagine the life she led, I can imagine it. She was born wicked. A wanton creature!” Pictures crowded into Harriet’s mind. The squire and the hard-faced woman who looked after his children, Bess and men … vague men. She put her hands to her face, covered her eyes, but the pictures remained. And when she uncovered them, a girl with blazing eyes faced her.

“How dare you!” cried Kitty, and tears spilled from her wonderful eyes and ran down her cheeks.

“How dare you say those things about my mother! She was good … good … better than anyone else in the world, and I loved her…”

Kitty threw herself on to the bed and began to sob now as she I had been unable to sob since her mother’s death. Harriet stared in dismay, first at the girl’s shaking shoulders, then at her feet on the clean counterpane. She wanted to protest; she wanted to whip the girl; but she did neither; she just turned on her heel and hurried out of the room. In the corridor she paused. What a handful! Bess all over again! She would subdue the girl, though. She would force the wickedness out of her. just as she would have forced it out of Bess had she been old enough.

Kitty was stifled in that house. It seemed that everything she did was contrary to her aunt’s wishes. At first she tried hard to please; she sat stitching with Harriet in the drawing-room until her head ached; she bent over the garden beds until her back ached; she worked in the still-room but hated the stains of fruit juice on her fingers, and she had no aptitude for the work.

How can she be so stupid! thought Harriet.

How can she care so much for all these things that do not matter, wondered Kitty. And she dreamed of Darrell, and thought of meetings in the wood, and of the day they would go to London together, for his Uncle Gregory had said he was too young to marry, and Darrell was hoping for support from his Uncle Simon in London.

“Wool gathering!” Harriet would snap.

“Head in the clouds! I do declare I’ve got an idiot for a niece.”

Kitty would merely smile and hug her secret to herself.

Insolent! Harriet would tell herself. Not a bit contrite! I believe she’s laughing at me! But Kitty was not laughing at Aunt Harriet; she was only sorry for her. because she had no lover to meet in the wood and must spend all her enthusiasm on preserves and her kitchen garden.

Every evening at dusk she slipped out of the house. Darrell would be waiting for her in the wood. He would kiss her and fondle her. and she would look up into his face and think how good to look upon he was and how much older he seemed than the very young man she had first seen in the coach.

“Why!” he cried impatiently, ‘do they put obstacles before us?

“Wait!” says my Uncle Gregory. How can we wait! Kitty, how can we?”

It was difficult. There she was before him. very young, desirable and desirous, Bess’s daughter. Very soft and so ready to yield; he dreamed of the way she quivered when he put his hands on her shoulders. He loved her tenderly as well as passionately. He had written to his Uncle Simon in London, and Uncle Simon was more human, more understanding than Uncle Gregory. A large, red-faced man, Uncle Simon, whereas Uncle Gregory was tall and thin. Uncle Simon was a free thinker; he Meed to foregather with his cronies in coffee and chocolate I houses, and listen to the talk; he liked a carousal in a tavern; he liked women. Besides, he was ready to approve of anything of which Uncle Gregory did not. So Darrell had written a letter to Uncle Simon.

“She is beautiful,” he had written, ‘and we want to marry. Uncle Simon, we must marry At the moment we meet in a wood. She has a strict old aunt, and I have Uncle Gregory …” He had tried to word it so as to make Uncle Simon laugh as well as to arouse his sympathy. He had great hopes of Uncle Simon.” Still, he did not let his hands rest too long upon her shoulders, nor look too much at her red, soft lips; he tried not to notice how green was the grass and how soft and beautiful the bank, with the violets growing there. It seemed to him too that the birds were urging him to love, mocking him a little. There was a song of Shakespeare’s that kept running through his head:

And therefore take the present time.

With a hey, and a ho, and a hey nonino… For himself he would take all the present had to offer, but he! loved her very tenderly, and outside the wood with its soft; carpet of grass, its sheltering trees and mocking birds, the world! was a cruel place. ;

The two girls, Peg and Dolly, knew of the meetings with Darrell, but there was nothing to fear from this. Kitty had given Peg a girdle of silk and Dolly a lace handkerchief, and no one had ever given them anything but advice and blows before. The clothes they had worn in the workhouse were payment for hard work; their board and lodging with Harriet were payment foil more hard work. But the girdle and the handkerchief were simply gifts, for she had given them, asking nothing in return. But even without the gifts they would have been on her side. She was beautiful and she was kind; they had no learning, but they did know it was natural to love. So they would carry messages for her. and whisper together about her, and try to be a little like her. They had made constant use of the pump in the yard since the arrival of Kitty; they washed their garments. Peg wore the girdle on her quilted petticoat of flannel; Dolly carried the handkerchief tucked inside her bodice.

Two weeks passed in this way. The squire was a frequent caller. He sat in the garden and complimented Harriet on her flowers, and he studied her vegetables with what seemed like real interest. It could mean only one thing, thought Harriet, and she lay awake at night thinking of it.

She thought it was a pity that Bess had had to die just at this time and force on her the duty of looking after her daughter. For she did not understand Bess’s daughter; she was almost rude to the squire, and he never seemed resentful, never even seemed to notice it. Sometimes he would look at her from under his bushy brows as though he were puzzled and interested but then, if you planned to marry a lady, you would be interested in her relations I Now and then, when Kitty was offhand with the squire and made Harriet cold with indignation and humiliation, he would turn to her, Harriet, and be so charming, almost like an accepted lover, as though he would teach the girl a lesson in good manners. It was gratifying, intensely so. Once she said to Kitty: “I do not understand you; you are positively unmannerly towards Squire Haredon!” And Kitty turned on her with flashing eyes, and cried out: “I hate that man!” Hate! What a word for a lady to use! And what had the squire ever been towards Kitty but indulgent, ready to overlook her rudeness?

“You will never find a husband if you persist in those manners, my girl!” she had said severely, for the girl was as vain as a peacock, and she thought that the best way of piercing her armour. And Kitty angrily turned on her with: “Your excellent manners did little to help you in that respect!” And then, just like Bess, all fury one moment and full of ridiculous demonstrations the next: “I’m sorry. Aunt Harriet. I didn’t mean that, of course. I know … there must have been people who would have liked to marry you … if you had wanted them… but… I do hate Squire Haredon. I can’t explain, but I do.” And Harriet had said: “Indeed, you foolish girl, you cannot explain; but I will thank you to be more civil to my guests.”

It went on like that for three weeks, with the squire a constant visitor, until one hot afternoon, a lovely afternoon when the roses were at their best and the lavender was full of fragrance with the bees dancing a wild delight about it.

Harriet, from her sewing-room on the first floor, thought she heard the sound of carriage wheels on the road; she looked from her window, but the trees were too thick with leaves for her to see the road clearly now. She returned to her sewing. At any moment now Peg or Dolly would come to announce the arrivals of the squire, and perhaps this very afternoon he would ask the question which must have been on his lips for weeks now] perhaps for years.

But the expected tap on her door did not come, so, she told!

herself, it must have been someone else’s carriage she had heard on the road. Feeling restive, she remembered how dry the dahlias had looked that morning. Poor things, they got little sun, tucked away near the summerhouse. If she wanted a good crop, when the more spectacular flowers had faded she must give them a little care. She went downstairs and took her watering!

can. ;

She heard voices as she approached the summerhouse.

Kitty’s voice! The squire’s voice! Then it had been the squire’!

carriage she had heard. She hastened forward, for she knew how unmannerly Kitty could be. She hoped … She stopped suddenly and leaned against the laburnum tree, which in spring time showered its yellow blossoms over the roof of the summerhouse. Their voices floated out to her; the squire’s was thick!

Kitty’s shrill. ‘ “Look here,” said the squire, ‘be reasonable, Kitty. God knows I’ve been patient. Why do you think I’ve been coming here life this … nigh on every day? To see you! And you know it, your little she-devil! Think I haven’t seen that look in your eyes? No.

listen, Kitty, I’ll marry you…”

Kitty cried: “Don’t dare touch me! I tell you I hate you!”

Nothing would make me marry you. I think … I think…”

Harriet realized that the rough bark of the tree trunk, pressed against her forehead, was hurting her. She stooped to pick up the watering-can which had fallen from her limp fingers.

“I hated you,” Kitty was saying, That first evening at the inn at Dorchester. I tell you, I hate the way you talk, and I hate the way you eat, and most of all I hate the way you look at me. Don’t dare to touch me! I’ll scream … I’ll call my aunt…”

He laughed, coarsely, horribly; Harriet could bear to hear no more. She sped past the dahlia bed, across the lawn; she shut herself in her bedroom, feeling numb, and as the pictures crowded into her mind she made no attempt to shut them out. He was a beast! Why had she ever thought…? And all the time he had been laughing at her! Letting her believe that he contemplated marriage with her. Thank God she had never betrayed her own thoughts! Thank God her father’s training had taught her restraint!

“Little she-devil…” The slur in his voice when he said that… you could hear frightful things in his voice, lascivious things. Oh, this was relief. She would never sit at his table now; she would never be the squire’s lady; but now she could look straight at the ordeal of sharing his bed and not be afraid, because it would never happen to her. She must suppress anger; she must nourish relief. That evening in Dorchester! Now she knew why he had sent the carriage. And Kitty, the sly creature, was her mother all over again, with wantonness in her eyes. It was a duty now to prevent the girl from following in her mother’s footsteps. She should be guarded with vigilance.

Up and down her room paced Harriet. She took her keys and went to the still-room; here was comfort. So clean, so neat -what joy in regarding those labelled bottles! Here was her life. All thoughts of George Haredon were to be thrust out of it for ever. Never again should she be so deceived!

Someone was knocking on the door.

“Come in!” she said calmly, and Peg came in and told her that the squire had arrived and was downstairs in the garden.

She went out to greet him. How grateful she was to her father! She had inherited no luscious charm from her mother, but she must be grateful for her father’s serene spirit.

“How do you do?”

His face was red and angry; he looked bewildered and younger than he had for a long time, almost as though he could not understand why the world was so unkind to him.

“How good of you to call, George.”

He sprawled on the wooden seat under the chestnut tree, sullen, trying to pretend nothing unusual had happened.