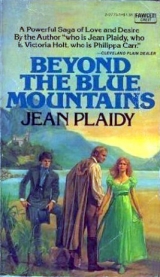

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 35 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

Audrey was romancing. If you had spent horrible weeks in Newgate, you knew it was no place to harbour angels. The poor child had had an hallucination.

“Audrey, finish your work and leave me. I wish to be alone.” She picked up the fragments of Marcus’s letter. What impudence! Of course I shall not meet you. And what would you do if I did? You would flatter; you would tell me you had never forgotten me, doubtless. You would … She tried to still the absurd fluttering of her heart. It was not Marcus of whom she was thinking, she assured herself, but of that absurd flight of fancy of her maid. Newgate did something to you, turned the brain. If you stayed there too long, doubtless you would suffer from hallucinations.

A lady … like an angel. She walked into that den of savages and she picked up one of the babies, naked, with his face half eaten away with some disease. Surely an angel… “Audrey!”

Audrey came over and stood before her.

“Who told you this story of a lady who was an angel?”

“I see it… I see it myself, M’am. He says to her: “Lady, you go in at your own risk,” he says, and she walks in. And her skirt rustled like an angel’s wings, and we was all afraid of her and somehow glad. And she picks up one of the babies…” Did anyone else see this… vision?”

“But M’am, they all see. They was all there … She wasn’t no vision, M’am. She was Mrs. Fry!”

“I have never heard of Mrs. Fry,” said Carolan.

“You will. Ma’am! The lady … another what come … said you will. She come and read to us sometimes … and then there was the needlework, and she said: “One day everybody will know about Mrs. Fry, know what she’s done for you poor souls.” Why should one waste one’s time talking to a crazy maid! She slipped the torn pieces of paper into her pocket. I shall not go. Of course I shall not go.”

Katharine was missing all day. She was with her lover of course. Carolan was tired and weary. She retired early and gave instructions that Miss Katharine was to come to her when she returned.

Katharine was sullen, already defiant, ready to forget the care of years for the sake of Marcus’s son.

“I wonder you’re not ashamed, chasing all over the countryside after that young man!”

“I am not ashamed, and do not chase after him. We met.”

“What do you think Sir Anthony will say if he hears?”

“I do not know, and I do not care!”

“You are a stupid girl, Katharine. Have you thought of what Sir Anthony is offering you?”

“Oh, Mamma. As if I wanted to be offered anything! Do not be so dreadfully behind the times. I suppose, before you married Papa, you decided it was right and proper that you should, and everything was just as it should be. People aren’t like that… so much … nowadays, thank heaven.”

Carolan’s face was hot with shame. It was almost as though Lucille Masterman was in the room, laughing at her. All right and proper! That was funny. If Katharine knew it. And it was all for her I did it! Oh no. Carolan, for yourself as well. No, for my child; I could not have my child born without a name. I did all that for her, and see how she repays me? She deceives me, she flouts my authority! She is threatening to run away with a boy who will never be any good to her, because he is his father’s son.

And Marcus and I will be related in some ridiculous way, and I shall have to see him, and… and… It was for her I did it this ungrateful girl, this wayward daughter. If she marries Henry Jedborough, it is the end of peace. It is Marcus coming back into my life. She must not marry Henry!

“You cannot marry without our consent,” said Carolan coldly, ‘and I assure you you will never have it.”

“Do you imagine you can keep us apart?” How like me she is! How her eyes flash! This is Carolan again, with her first love. Everard.

“We shall refuse our consent, your father and I.”

“My father, would give it if, you would. He would help us, I know.”

“Your father is all in favour of your marriage to Sir Anthony.”

“But you could make him in favour of my marriage with Henry.”

“As if I would! You are a stupid child. You know nothing of the world.”

“Does one need to know the world in order to know whom one wants to marry? You will be telling me next that unless one has been in England one cannot pick one’s mate!”

“Don’t be so stupid, Katharine!”

“It is you who are stupid, Mamma.”

“My head aches. You are grieving me very much. When I think of all I have done for you …!” The old plaint of the defeated mother, she thought, fighting for that place in her child’s affection which is lost to a lover.

“Oh, Mamma, please! I did not ask to come into the world, did I?”

No, she did not. It was I who wanted_her; it was I who used about No, she did not. It was I who wanted, .. ..-her before she was born, to get what I wanted.

“Katharine, you know how deeply your father and I feel; this. Cannot you realize that we know better than you do?”

“No, Mamma, you do not know better. It is for each person to manage his own life, surely. Because you made a good job of yours, it doesn’t follow that you can make a good job of mine. Mamma, I do not want to go on deceiving you.”

“Oh no? You did that very successfully, for how many years?”

“Only because it was necessary. Please give your consent to our marriage, Mamma … darling Mamma! We have loved each other so much, you and Papa and all of us. I am going to marry Henry; let us be happy about it.”

“My dear child, you talk romantic nonsense. It is your happiness we think of. You know how that boy has been brought up. You know what his father is a convict!”

“Mamma!”

“I was different, I tell you. It was a mistake. Good gracious, child, do you believe your own mother to be a felon?”

“No, no. Mammal Dearest Mamma…”

“It is very different with him. He was a thief. He was here before. He escaped and was sent back again. I know his record.”

“His record, Mamma, is his affair. It is Henry I propose to marry.”

“But he is Henry’s father!”

“Mamma, if you had done something terrible, you would not expect people to blame me!”

What did she mean? What did she know? It was that wicked old Margery. Did she feel ghosts in this house?

“Oh, Mamma, I know you will be reasonable. You won’t blame Henry because of what his father did?”

“I will never give my consent to your marriage with that boy.”

“You must know that we shall never give each other up.”

“I should advise you not to do anything rash. You are our daughter; you are seventeen years old; your father could have him sent to prison for abducting you.”

“Oh, Mamma, you could not be so cruel, so… so wicked!”

“There are many things I would do if I were driven to them …”

“Mamma, you frighten me.”

“Ridiculous child! Why should I frighten you?”

“You must not be cruel to Henry, Mamma!”

“I hope you will be sensible, darling. You have no notion of how exciting life in London can be, if you have money and position. Suppose your father insisted on your marriage to Sir Anthony! You would be grateful to him to the end of your days.”

“If Papa knew how unhappy I should be, married to Sit Anthony, he would never force me to it… unless you insisted.”

“My dear child, do not stare at me like that.”

‘you look different…”

“Stupid! Well, leave me now. It is for your father to decide.”

“No. Mamma, it is you who decide. You could persuade him, and I know he would want me to be happy. You could tell him how there is one way of making me happy.”

You ate stubborn, Katharine. Go to your room. My head aches. Think of what I have said to you. Think of what will be best for us all.”

Katharine went to the door. She looked dazed, as though she were seeing Henry dragged from her. Van Diemen’s Land! It’s hell on earth, and hell on earth is surely as bad as hell in belli “Audrey!” Carolan called, when Katharine had gone.

“My head aches. Sprinkle a little perfume on a handkerchief, and lay it across my forehead.” Audrey gently did so. Thank you, Audrey.”

Sleepily she smiled, and thought of Gunnar, the cold man whom it was so easy to rouse to sudden passion, even now. Queer faithful Gunnar. She had chosen him and the house with its comforts. She had turned away from the station, back of beyond, and quick hates and quicker love. And she did not know now whether she had chosen the right way. No way is right -perhaps that is the answer. Here she was, a beauty at thirty-six; she did not eat recklessly of the sweets of life, as poor Kitty had done; she was plump, bat not over-fat. How would she have grown in the station? A slattern? That wild life would make demands on a woman, take toll of her beauty. And Marcus ever had a roving eye. He would never have been true, and she would have hated him for that, and perhaps she would not have been true either, for she was hot-tempered and impulsive, and would have wanted to pay him back in his own coin.

How should you know which was the right road for you and no road was sunshine all the way I But she wanted so desperately to have done something fine with her life. She was full of memories tonight. There was something Esther once said about her being a pioneer; and she had answered that she would have liked to have been the Good Samaritan, but she greatly feared that she would have passed by on the other side of the road. It was only when she fell among thieves that she cared about other victims. And yet a woman had walked into that den of savages, and she had smiled, and her smile was the smile of an angel, and her dress rustled like the wings of an angel, and she picked up a naked child, suffering from some hideous disease. Without feat she had done these things, and only a saint could go among those caged beasts and be without fear. What power had she?

“Audrey! Audrey! Come here.”

Audrey came and stood by the bed.

“Bring a chair, Audrey, and sit down. I would hear more of this Mrs. Fry.”

Audrey kept telling the story of her coming. It was like a miracle. Dead silence, and her standing there. An angel. And she picked up the little child. And he was naked and his face was half eaten away … Only those who had lived in Newgate could understand that that was a miracle. Carolan, her face pressed against her pillow, saw it clearly, as though she had been there when it happened.

Audrey stumbled over her words, but she gave a picture of a changing Newgate. People who were taken in now did not suffer quite so intensely, as Carolan had suffered. Change had been worked by an angel in a Quaker gown. Audrey talked of the readings, of the sewing; how it was possible to earn money while you were in Newgate. There had been the visitation of this angel, and she had spread her wings over the prison and given her loving care to those sad people.

Tell me about her! Tell me about her! What does she look like?”

“I couldn’t say … She’s different … M’am. That’s all you know…”

“Different? Different from me? Different from you?”

“She makes you feel you ain’t all bad, M’am. She makes you feel you might have a chance.” A chance? A chance?

that’s how she makes you feel.

“What sort of chance?”

“I dunno. Just a chance She’s different.”

“Is she beautiful?”

“Not like you, M’am. Not that sort of beautiful. She’s different … I dunno. She makes you feel you’ve got a chance.”

“Why did you not tell me about her before?”

“I dunno, M’am. You didn’t ask. She come to us, Ma’m, when we was waiting on the ship, to sail, and she talked to us … she talked lovely.”

“What did she say?”

“I dunno. She made you feel you wasn’t all bad. She made you feel you’d got a chance … And it was ‘cos of her we’d come down closed, they said. She wanted us closed in. She said it ought to be …” Carolan said: “Leave me now, Audrey. I want to sleep. I have a headache.” And Audrey went.

It was all coming back vividly. The arrival in Newgate, the fight, the talk, the smell, the ride to Portsmouth. Mamma, Millie, Esther so young and pure, praying in that foul place and the whale-oil lamp flickering in the opening high in the wall. The ship. The deck. Hot morning, and coloured birds of brilliant plumage, and the horrible man with the eyeglass, and Gunnar… What was the good of having lived I wanted to be a saint. I wanted to be like Mrs. Fry. I would have gone there; I would have been unafraid. I would have picked up the little child. I… I… I could have made them feel there was still a chance. But what have I done with my life? What indeed!

She began to shiver.

“You should have been a pioneer. You could have been, Carolan!” No, Esther, no! I should have passed by on the other side of the road.

But I wasn’t all bad. I should have been a good wife to Everard. I should have cared for the poor and I should have understood their troubles and helped them. Perhaps if I had married Everard I should have been different. I might have been good -not wicked. I might even have been like you, Mrs. Fry.

“Marcus!” she cried.

He leaped from his saddle and tied his horse to the tree. She noticed his hands; they were brown with the weather.

He said: “I knew you would come!” with all the old confidence, and as though years had not passed since their last meeting.

“Carolan! Carolan! Why, you have scarcely changed at all!”

“Rubbish!” she said.

“I am years older. I am the mother of six children.”

“Well, Carolan, Carolan!”

She remembered his old habit of repeating her name; it still had power to move her.

This is a great day in my life!”

The old flattery that meant nothing. He would flatter old Margery just because he could not help flattering women.

“Are you glad to see me, Carolan? Do you find me changed?” He had come forward; he had taken her hands; his eyes were older, with experience, with weather; but the charm persisted.

“Naturally! Since I have come a fair ride to see you. But we did not come to talk of ourselves.”

“Did we not?” He was still holding her hands.

“Not such an uninteresting subject! Carolan, how has life been treating you, Carolan?”

“Very well, thanks. You too, I think.”

Very badly, Carolan, since I lost you.”

“Oh, Marcus, you are too old for that sort of talk, and I am too wise to listen to it. It is of our children that we must talk.”

“My Henry,” he said, ‘and your Katharine. What a sly old joker life is, Carolan! Would you have believed eighteen years ago, when we looked forward to our happiness, that one day we should meet in this wild spot to discuss the marriage of my son to your daughter?”

She was determined not to fall into that reckless mood which he was trying to draw round her like a web. She felt strong in her pride and her dignity and her knowledge that she was Mrs. Masterman of Sydney.

“It certainly does seem ironical, but as it happens to be a fact, shall we say what we came to say? Why did you want to see me?”

To beg you to put no obstacles in our children’s way, Carolan. They are so young, and the young are so lovely, so helpless. It would be unbearable if they too were to lose their happiness. Could history repeat itself so cruelly? We must prevent that happening.”

“You are still the same,” she said, angry without quite knowing why.

“You talk, and your words must not be taken seriously. You are suggesting, of course, that we lost our happiness; we did not. We are both well pleased with ourselves.”

“You found perfect happiness, Carolan?”

“Oh, let us stop this absurd, sentimental talk! Who ever found perfect happiness yet?”

“But if you cannot find it, Carolan, it is something to think you see it in your future. I thought that, Carolan, eighteen years ago in old Margery’s kitchen.”

“When you decided to marry Esther? How is Esther?”

Real pain seemed to come into his eyes, but of course he was an adept at endowing each mood with a semblance of truth.

“No,” he said, ‘not then! It was when I thought I should marry you. Oh, Carolan, Carolan, what a witch you were. You bewitched me. I had to obey you. I dreamed of you all day and all night. I believe I never stopped dreaming of you.”

She looked beyond him to the mountains. She thought of them as Katharine’s mountains, because Katharine had loved to talk of them when she was a little girl.

“Listen, Marcus,” she said.

“I love my daughter, more than anyone in the world, I love her, and I am very unhappy because she is angry with me. She is going away from me. If she were your daughter, would you not want the best possible for her?”

“Indeed I would, Carolan.”

“Well, understand this. There is a man who would marry her. He has everything money, position. He is kind and tolerant, and, I think, very much in love with her. He can take her to England; he can make her happy. But she is obsessed, and it is your son who has obsessed her. She sees no happiness but with him, and I will not have my daughter spoil her life!”

“Spoil her life, Carolan!” he said earnestly.

“Why should she spoil her life?”

“You know the life as well as I do. What is it, for a woman? She would have to live in the wilds; she would meet scarcely anyone. I can see her in London, sparkling for she is only budding and will bloom gloriously. London is her proper setting. Money… Position… that is what I want for my daughter. How do we know what will happen here? This is a new country, heard stories of the terrible things that can happen on lonely stations. Men are more desperate here; laws are less rigid. No no! She would very soon forget your son. Oh, I imagine he is very like you were once; I imagine he knows how to charm a young girl. He will hurt her, I know he will… as you hurt me, as you must have hurt Esther and your Lucy and Clementine Smith and God knows who else. I want her to have security. Who knows better than I what can happen to a woman who is unprotected and …”

“Carolan, Carolan, where is your good sense? She will be secure enough with Henry. He will love her, I promise you. He will look after her.”

She was emotional: it was not so much of Katharine that she was thinking, but of herself and Marcus, and tears of self-pity welled into her eyes, for his charm was potent as ever. And she thought of the years immediately behind her, and the ghost that had haunted her for eighteen years and of what wild, free happiness might have been hers for the taking.

He came to her and slipped his arm about her. He had seen the tears in her eyes.

“Carolan,” he said, ‘we are still young.” She spun round to look at him, and he threw back his head and laughed.

“Carolan. Carolan! I am just past forty. Is that so very old? You are thirty-six surely in your prime. Carolan, look at those mountains! Are they not beautiful? Do you feel them beckoning you? They are wild, they promise adventure; there is a new country beyond them. Carolan, Carolan, why should you go back to Sydney? Why should you, why should you, my darling? This is linking up, my dear, linking up with eighteen years ago. You are mine, and I am yours… that was how it was then; that is how it is now. That cannot change.”

“Marcus!” she said.

“Marcus!”

He caught her to him and kissed her; she kissed him wonderingly.

“It is strange,” she said, ‘to feel young again. It is years since I felt young.” She had lost control for a moment, but she was resolved it should be for no more than a moment. She wanted to capture that feeling of recklessness, she wanted to know again what it meant to love without thinking … just to love. She had jail that moment; she would remember now.

That is all,” she said.

He shook his head.

“Carolan, come away with me. Why should we not? You would have come with me… once.”

“Once!” she said.

“But so much has happened since then.”

“A moment ago,” he said, “I thought you were still my sweet and beautiful Carolan whom I loved in your father’s shop, and in Newgate, and on the ship and in Margery’s kitchen. You broke my heart when you went to him.”

“And you mine when you went to her!”

“It was nothing, Carolan. Did you love him?”

“I am fond of him,” she said.

He kissed her angrily.

“Why did you spoil our lives?”

“It was you who spoiled our lives, Marcus.”

“No, it was you… you with your conventional ideas.”

“It was you with your philandering, your lies, your cheating … How do I know that even now you are not cheating! You may be laughing “Oh, this is funny! I am amusing myself with Mrs. Masterman of Sydney!”

“Do not speak his name.”

“It is my name I speak.”

“You are Carolan, nothing but Carolan! Why do I love your daughter? Because she is so like you! Why was my life brighter when she came and sat on the veranda and talked to my boy, Henry? Because she is so like her mother.”

“Why do you always say the things I most want to hear?”

“Because I love you.”

“Oh, Marcus, it is too late to talk of love.”

“It is never too late to talk of love. Carolan, never go back to Sydney! We will go to England … to London. It will be a different London from that wicked city in which we met. We will conquer it this time, Carolan.”

“It is too late. Do you think I would leave my children and my husband?”

“If I had twenty children I would leave them for you!”

“Please, Marcus, do not talk of it any more.”

“If I talk enough you will understand how it is we cannot throw away this chance of happiness.”

“There is no chance, Marcus. We lost our chance eighteen years ago.”

“My darling, while there are boats to carry us away from this place, there is still a chance.”

“I would never leave my family.”

“I am your family. I am your home. You are mine and I am yours. You must understand that.”

“But Marcus, people change in eighteen years. I have changed.”

He kissed her; he held her against him and he laughed with joy.

“You have not changed; you are my own sweet Carolan. You will never go back. Always I have vowed that if I could talk to you, if I could but hold you like this, I would never, never let you go again. I am no longer young, Carolan, I am old in wisdom. Never shall I let you go again, my darling. I will keep you by my side always. You are my comfort, my love, my darling!”

“I should not have come,” she said sadly.

“I am only making you unhappy, and myself unhappy. I was resigned. I will never, never leave my husband. I have sworn that, Marcus.”

“What oaths you have sworn go for nothing, darling. You are mine you cannot deny that.”

“These oaths I have sworn in the dead of night, when I wake up trembling, or when I have been unable to sleep. I have sworn, Marcus. He lies there beside me; sometimes he is sleepless too, and I wonder what he is thinking. I have said “I will never leave you, Gunnar. I will do all I can to make you happy.” It is because of that… because of what happened, Marcus, I have never told anyone, but I will tell you now because I owe it to you, Marcus. I must tell you why I cannot go away with you. How I long to. I cannot pretend any more; I have always loved you. I could have killed you and Esther … but there is no one but myself to blame; how well I know that now! Listen. Marcus. I am a murderess. That is why I cannot go. Did you ever hear talk in Sydney? Did you hear how Lucille Masterman died? I was to have Ms child, Marcus, and I was alone and afraid, and I was brutalized; Newgate did that to me or so I tell myself! Perhaps it is just an excuse; perhaps if you are strong, nothing can maim you.

“She used to take a drug, Marcus. I knew about it; so did Gunnar. I used to think it would be so easy for her to take an overdose. She did not want to live; I did … desperately. I wanted a good life for my child. How do we know what motives prompt our actions– I tell myself I did it for my child; but did I? Did I do it for myself? He was so kind to me; he said I should go away to discreet and sympathetic people, but I laughed at that; I laughed it to scorn. No! I said, you must marry me; we must have a real home for my child, or I shall marry someone else. You remember Tom Blake would have married me then. Gunnar loved me; he loved me as you would not believe he could love anybody; he wanted children, and she had cheated him. Marcus, do not look at me like that! Put your arms around me, hold me tight. She has haunted me since; she will go on haunting me. Sometimes I feel she will drive me mad. She was so weak, Marcus, and she did not greatly want to live. You see, the bottle was there; it should have been so easy. She had bought the stuff from an ex-convict who dealt in illicit medicines. She used to drug herself to get some sleep. She always imagined herself ill. And I think she knew how it was with me; I did my best to tell her … without doing it in so many words. I put the idea in her head that it would be so easy… just an extra dose, and then she would sink into that deep peaceful sleep of which she had talked to me.”

Marcus took her by the shoulders, and looked into her eyes.

“Carolan, you… you killed her!”

She threw back her head.

“Yes,” she cried, “I killed her! I killed her! No, no! I did not pour it out into the glass and give it to her; I did not kill her like that. I do not know who did that. Perhaps she took that overdose herself perhaps he gave it to her. Sometimes I picture his going into her room.

“You look tired, Lucille!” I can hear him saying it.

“Have you not some medicine that will make you sleep? Sleep a little; it will do you good. I will get it for you…”

You see. if he did that, I drove him to it. I taunted him with pictures of myself married to Tom Blake. I carried his child, and I threatened to cut him off from it. He is a strange strong man; I do not know whether he would do that; I have never known. Often I have thought it possible. It has been between us all our life together. Did he? I ask myself, but I have never dared ask him; I am afraid of the answer. But Marcus, listen. Whichever it was, whether she took that overdose herself, or whether he gave it to her, I am the murderess, for I created that situation which made it the only way out. For my daughter, I said! But it was not for my daughter it was for myself.”

She was sobbing wildly in his arms. She was laughing; she was crying.

“You see me, Marcus. I am wicked. There is no goodness in me. And I so wanted to be good, Marcus. Audrey baa told me of a woman, a wonderful woman. Marcus, she is changing Newgate. Were we to go there now perhaps we should not recognize the place. That is what I like to think … We should not recognize it. She is a saint, this woman. How I envy her. I say to myself “That is what I might have been. And what am I… a murderess!”

He said: “Carolan, Carolan! How wild you are! What absurd things you say. You are not changed at all. You are still the same Carolan, the same sweet Carolan.”

“Please do not say my name like that. I cannot bear it. Do you not see that I will never leave him? You see what I have done. You have haunted my life; you will continue to do so. Oh, yes. I have thought of you constantly, longed for you … No, no, please do not! It is useless. I cannot be happy with him because of you. I couldn’t be happy with you, for always I would remember what he had done … or perhaps he did not do… but he is good and has a strong conscience, and he suffers just as though he had done it, because he knows why she died. She died because of what we had done, and he knows and I know it.”

He said: “Carolan, I could make you forget.”

She answered: “Oh, Marcus, I am afraid for my sweet daughter. She is headstrong, as I was. Sometimes I think that the women of my family are doomed to sorrow. There is some story about my grandmother; my great grandmother too. And then my own poor Mamma; she has told me the story of how she lost her lover to the press gang. How different her life might have been had my father not been taken by the press gang!”

Marcus held her against him, stroking her hair.

“The press gang is done with. Carolan. It ended with the wars.”

“My Katharine will never lose her lover to the press gang then!”

“Oh, Carolan, Carolan. do you not see a new world opening before us? We are going on … on to better things. You tell me even our old evil Mother Newgate is changing her manners. Slowly but surely, my Carolan. There is something here. Let us not think of our own little tragedies, darling. Look on… to our children and their children and their children … generations of them… going on and on! The press gang gone, Newgate changing! And what changes will our Katharine and Henry know in their lifetimes!”

“Marcus, you see what I mean … I want to make sure of safety for my daughter…”

“You cannot make sure of safety for anyone, my sweet Carolan.”

“But you can! You can!”

“No, darling. They will work out their own lives. We cannot interfere. People should never interfere; it is only the time in which we live that should influence us, and times are changing. Carolan. What if your mother and father were young in these days? No press gang to rum their lives. Mother Newgate is changing her face! Who knows, some time there may be no Newgate at all, no possibility of the innocent, such as you were, being caught up with the law; no need for the weak, such as I was, to break the law. Carolan, Carolan, do you not see a wonderful world lying ahead of us?”

“You talk wildly. Marcus. You always did. There is much cruelty in the world still. There always will be. How can we overcome all the poverty and cruelty and injustice?”

“Look there, Carolan! Look to our own Blue Mountains. How long ago is it that we thought there was no way across that mighty barrier? Impassable! people said. The natives told absurd stories of demons who had sworn we should never pass over their mountain. But we did, Carolan. We are across; and on the other side is a fertile country, undeveloped yet, undeveloped as the future. But it is there, and it is wonderful, and it is worth the heartbreak and the struggle to get across. That’s how I see it, Carolan, the way across the Blue Mountains to a beautiful future. Our grandchildren, Carolan … Our great great grandchildren … they will have their difficulties, as far removed from us as it is possible to be. There will always be a range of mountains to be crossed perhaps, but the struggle is worth while, Carolan, when you get to the other side.”

“They want to live beyond the Blue Mountains,” she whispered.

“Let them, Carolan! Oh, let them! Perhaps you are right: perhaps she would be wiser to marry her knight and go to London Town. But it is not for us to say. The future does not belong to us, Carolan, but to them. They must have freedom; we must give them that. You understand, Carolan. You do understand?”