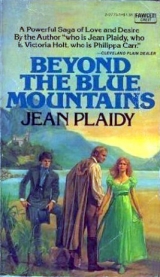

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

Carolan said: “Give me your glass, Esther.” She took it, flashed a warning glance at Esther, smiled at Margery.

“There!” said Margery.

“Drink that up, you sly little cat! And don’t think you deceive me for a minute with your praying to God.”

Carolan wanted to comfort Margery, poor Margery to whom youth meant a good deal because love went with it.

Esther took the glass with trembling fingers. Her nerve had been broken in Newgate; temporarily she was lulled into a certain security, but she could be jerked out of it in a second. Here in the Masterman kitchen she could do the work allotted to her, the convict garb did not hurt her because she was meek of heart and she was innocent; she took on a good deal of Carolan’s work, and enjoyed doing it, for she felt she owed to Carolan a debt which she would never, never repay as long as she lived. She said her prayers each night, before she slept the sleep of a quiet conscience. But embedded in her mind was the memory of the agony she had endured in Newgate, when those women surrounded her, stripped her of her clothes, and did to her what she preferred to forget and never could as long as she lived. Sometimes she would awake in the night, screaming, because she had dreamed that that ring of hideously cruel faces was closing in on her. Then Carolan, strangely gentle, unlike herself, would lean over to her bed, take her hand, waken her.

“It’s all right, Esther. It’s all right. You’re not there now. You’re here … It’s all right here, Esther.” What she owed Carolan she could never repay, and what joy it was to do the hardest tasks for her! In it was the glory of the hair-shirt, of the stony pilgrimage, of hardship and suffering. And now, with Margery’s hard eyes on her, saying “Drink that up!” she caught again that spirit of Newgate, the tyranny of the strong over the weak, the hatred of the impious for the pious. And Carolan, her protector, was urging her with her eyes to sip, to feign to drink. Carolan, her eyes alert, Carolan grown wiser, sensing danger.

“You too, me love!” Margery’s eyes caressed the face of the girl beside her. It was pleasant to turn back to memory. Might be me own young daughter, thought Margery. Like her to be! We’d get on. Only, if she was my daughter I wouldn’t have had her so haughty. Fun it would have been to listen to a daughter’s romances, rather than suffer the uncertain glory of romancing oneself.

“Fill up,” said Carolan.

“Come, Jin! Come on. Poll! Come on, James,” cried Margery. The bottle was empty before she had done. She lay lolling back in her chair.

Carolan twirled the gin in her glass. The effect of it was strange. It made her want to cry, cry for Haredon and its comforts, cry for Everard. For Marcus? She was not sure which. The lamp flickered up suddenly. The oil was running low. Jin folded her hands on the table and glanced at James; James fidgeted and started to talk to Margery, who laughed heartily over nothing and pathetically tried to reassure herself that that slut, Jin, wasn’t there. Poll was crying softly for her baby. Esther had drunk too much gin; it gave her a look of fever; Carolan thought her very beautiful tonight.

Margery said suddenly: “Shut up, snivelling. Poll! Why, what Mr. Masterman would say if he was to come down here I couldn’t think. And what of her bath? Good gracious me, look at the time. She’ll retire at eleven, if the others don’t. Doctor Martin’s orders if you please. And a hot bath she wants, before getting to bed. It’s a wonder to me she don’t catch her death. Jin! What are you thinking of? Get up, you lazy slut! Get her cans of hot water. There’ll be trouble in a minute. Why, it only wants five minutes to eleven!”

Jin drained her glass. From under her sullen brows she watched Margery. She was a little afraid of her. Jin’s stay in prison and again on board the prison ship had taught her the folly of flouting authority. Margery had not used the whip yet, but she might for some offences. Jin did not like the thought of the whip. She had often shuddered at the sight of the triangle in the yard. She had seen one of the men convicts whipped; she had run away, but she had heard the sound of the whip swishing through the air, and the sickening thud of its fall; she had heard the agonized screaming of male voices. No, no. There was not one of them in the basement kitchen who would dare to flout authority completely.

Jin stood up. She clutched the table. She swayed. Margery was beside her, gripping her shoulders, breathing gin fumes over her dark face.

“Ye’re drunk, me lady! Drunk!” She caught the girl’s ear and pinched it hard. She laughed almost with relief. If Jin was drunk, that would account for her boldness. Drink and love! she reasoned. If you were under the influence of either you couldn’t be taken too much to task for what you did. She pushed Jin back into her chair.

Carolan said: “Shall I take up the cans of hot water?”

Margery nodded, and fell into the chair next to James.

“Let me do it,” said Esther.

“They are heavy, Carolan. And you know how you hate carrying things!”

“No!” said Carolan.

“You have had too much gin. I can see you have, Esther, so it is no use saying you have not!”

“Ha ha!” cried Margery.

“These praying people! Just show them a gin bottle, and they are as bad as the rest. Look sharp with the cans, me Jove. I don’t want complaints.”

A queer excitement filled Carolan. She had seized on the opportunity of getting upstairs. She wanted to be caught up in the excitement of the party. She longed to go to a party, to wear a beautiful dress. But first of all it would be necessary to have a bath. She grimaced at her hands; they were grimy and beneath the nails were black rims that it was impossible to eliminate.

She filled the cans. Esther came to her.

“Are you sure, Carolan?”

“Oh, go to bed, Esther! I am absolutely sure.”

When she carried the cans through the kitchen, Jin and Esther and Poll had already gone into the bedroom. Cautiously, for the cans were heavy, Carolan mounted the back staircase.

On the first floor of the house was the suite occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Masterman. She had seen it once when she went to help Jin clean up. This was the first time she had been allowed to roam about the house by herself, for newly acquired convicts were rarely allowed upstairs alone. It was the unwritten law of the establishment, and was a sensible enough rule, she had to remind herself. A Sydney servant would very likely be a desperate creature. She smiled, thinking of Mr. Masterman. She supposed he had a dossier of them all. They would all be neatly labelled; for example, “Carolan Haredon, thief.

Outside the suite of rooms she paused. Mrs. Masterman’s room was at the end of the corridor, and between it and Mr. Masterman’s there was a smaller room where they made their toilets. The house had been planned with care. There were doors connecting the two larger rooms with the toilet-room, and that itself had yet another, opening on to the corridor. Mr. Masterman had planned the house, Margery said. One had to admire his methods.

Carolan set down the cans outside the door of this toilet-room, and knocked. There was no answer, so she went in. It was a fairly large room, for all the rooms in the house were large. There was a hip-bath in the corner, and a long mirror. There were several cupboards. On a table near the mirror were cosmetics and bottles of perfume. It was pleasant merely to be in such a place.

But she must not stand about, letting the water get cold, or she would not be allowed to come up here again. She went across to Mrs. Masterman’s door, and knocked.

She heard a sigh, then a very weary voice said: “Come in.”

Mrs. Masterman was in bed. The blue frock lay on the floor, and beside it the silver slippers. Mrs. Masterman’s thin fair hair was spread out on the pillows. She looked very tired.

She said, without turning her head: “Oh, is it my bath? I’m too tired now …”

“I will take the water away,” said Carolan.

The sound of her voice, cultured, unlike the husky tones of Jin, made Mrs. Masterman turn her head slowly.

“Oh…” she said.

“Oh…” And then: Take my frock and put it away, will you? It goes in the cupboard in the toilet room’ Weary eyes watched the yellow-clad figure walk across the room and stoop to pick up the dress.

“Have I seen you before?” asked Mrs. Masterman.

“I do not know,” said Carolan.

“I have seen you.”

It was not like a conversation between mistress and convict servant. It was like one lady paying a call on another.

“I think I should have remembered if I had,” said Mrs. Masterman.

“Give me one of those pills on the table, will you? A glass of water is what I have with the pill.”

Carolan was aware of Lucille Masterman’s very white hands lying on the counterpane.

Thank you. I have very bad health.”

“I am sorry,” said Carolan.

“Sometimes I scarcely sleep a wink all night.”

That must be very unpleasant.”

“It is. Thank you. Doctor Martin says these pills are wonderful.”

“I trust you find them effective?”

“I do. Although of course one gets accustomed to taking anything. Good night. Hang the dress up in the cupboard, please.”

“I will,” said Carolan.

“Good night.”

Lucille called her back when she reached the door.

“Lock it, please. And when you have locked it, will you push the key under the door?”

“Yes,” said Carolan, and went out and did so. It was rather an extraordinary experience. She felt intoxicated with success. It was the gin perhaps: it was such heady stuff. It made her excited because for the first time since she had been thrust into Newgate someone had treated her as she used to be treated in the Haredon days; and this the mistress of the house!

She opened a cupboard door. It was filled with dresses. Velvets and brocades, soft wools and silks. She rubbed her hands over some of them, and shuddered at the rasping sound they made as they caught in her rough skin. It was like a protest.

She held the blue and silver dress against her, and looked at herself in the long mirror. Carolan Haredon of Haredon! All that suffering, all that misery, had scarcely changed her at all. To wear that dress … only for an instant! To recapture the joy of going to one’s first ball!

Colour burned in her face. She tiptoed over to the door of Mr. Masterman’s room. Very cautiously she tried it. It was locked. This was safe. Mrs. Masterman was in bed. Mr. Masterman was still with some of his guests. It would only take ten minutes. Ten minutes of joy, and no fear of discovery… or very little, and she was reckless … reckless for the feel of warm water on her body and the caress of silk against her skin. She went to the hip-bath; she would be quick. She slipped off her clothes. She turned to the mirror so that she could see herself, tall and shapely, youthful, graceful. What joy it was to be free of the convict garb!

She scrubbed herself gleefully. She kept her eyes on the two doors. She could not help it, but the fear of discovery gave her an added sense of excitement.

When she stood before the mirror, clean, she felt she had washed off all the grime of Newgate and the prison ship. Perhaps some other time, when the coast was clear, she would bring the cans of water for Mrs. Masterman and use them herself.

Now just a glimpse of herself in the blue frock, and then back to the yellow.

She took it up; she slipped it over her head. She had forgotten that Mrs. Masterman was a smaller woman than she was. She struggled, and as she stood there, the frock over her head, she heard a footstep quite close. She was not sure which room it came from, Mr. Masterman’s or his wife’s. Panic seized her, she struggled. She must get into her yellow frock quickly; she was sobered suddenly; she realized what discovery would mean. Punishment… and what was punishment for a convict servant? The whip? She began to shiver, and as she stood there, with the dress half over her head, the door opened. Frantically she pulled at the dress; it fell about her bare feet, and through the mirror, for she dared not face him, she saw Mr. Masterman standing in the doorway of his room. He stood very still, like a great idol carved out of stone, awful, terrible.

He said: “What is this?” And his voice was harsh. It had a trace of the London streets in it; a hint of studied culture.

She had no words; she was dumb with terror. She could only think of the sound the whip made as it descended through the air.

“Who are you?” he demanded, and took a step towards her.

“I

don’t recognize you.”

Still she could not speak. Her mouth was dry, her throat parched.

She noted clearly the fairness of the hair about his face; the pale skin beneath it; the eyes that were grey-green like the sea on dreary days. Now those cold eyes had seen the garments lying by the hip-bath, had taken in the significance of it all.

“You’re from the kitchen,” he said.

“Yes.” Now her voice had come back she felt better. To hear it gave her courage; she felt herself once more. If she were going to be punished, she would accept punishment, and she would not let him see how frightened she was.

“And why did you do this?” he asked.

She answered simply: “She did not want her bath. I did. She told me to put that dress away; I wanted to see myself in it, so I … put it on.”

“You are a pert young woman,” he said.

“And very disrespectful.”

“You asked me,” she flashed, ‘and I answered.”

His eyes went over her, slowly, from her flushed face and tousled hair to her bare feet. It was the coldness of him that exasperated her, that aroused her fury; and when that was aroused, she could never give a thought to the consequences. A lump was in her throat; she was choking with anger and self-pity.

“I suppose you will have me whipped for this,” she said.

“I don’t care!”

“Oh? You do not mind the lash? You have experienced it? No? Is it not rather rash then to speak so lightly of it? Perhaps when you know something of it you will not be so contemptuous!”

“It is well for you to be so calm. You have not been dragged away from your home. You have not seen your father murdered, nor your mother die of neglect and cruelty. You have not lain in stinking Newgate and nearly died on a foul prison ship! You have not been taken into … into someone’s house as a slave…”

Her voice broke; tears began to stream down her face. He walked away and stood with his back to her.

“Doubtless,” he said, “You are quite innocent of any crime.”

“I am innocent!”

“Of course! So is every convict I have ever met. They only rob and murder; that is perfect innocence. Now perhaps you will be good enough to get out of your mistress’s clothes and into your own. Perhaps you will be good enough to keep to your own quarters.”

If only he had shown a little anger, she would have liked him better. It was that coldness in him which exasperated her beyond endurance.

He turned his head slightly and gave her a swift look as though he found the sight of her too loathsome to be endured for more than the briefest second.

“Please wait,” he said, ‘until I have gone. I notice you have the charming modesty of our Newgate friends!”

The door closed; she heard the key turned in the lock. She looked at herself in the mirror. Her cheeks were scarlet; her eyes brilliant with tears. How long had he stood there, watching her struggle into the frock? She put her hands to her cheeks, and a burning shame was in her eyes. The beast! The coldblooded beast! How she hated him! There were none quite as loathsome as the coldblooded. Anger one could forgive, but that cold, calculated sarcasm… She took off the dress quickly. She was terrified he would come back. She got into her own clothes; she could not help noticing, even in her distress, how different she looked. She tried to stifle her sobs. He would hear; he would smile with satisfaction, the loathsome brute! She imagined his coming to the yard to witness her punishment. It made weals on your back, Marcus said, weals that left their mark for ever, that branded you.

She poured the water back into the cans, spilling a little on the floor, and hung up the dress, terrified all the time that he would return.

When she got back to the kitchen, she found the others had gone to bed. She emptied the water away and went into the communal bedroom.

There was a candle burning. She saw James and Margery clasped in each other’s arms; Poll was crooning over her. doll; Jin was snoring slightly.

Esther was awake though. She whispered: “What a long time you’ve been!”

Carolan answered quite steadily: “I had to put her clothes away.”

“I’m glad you’ve come back; I was frightened.”

“You are too easily frightened.”

“I know, Carolan, I know! I wish I were brave like you.”

“Well, get to sleep now. Good night.”

Brave! That was funny. She was trembling all over. She could feel the lash cutting into her flesh.

How I would love to put it about his shoulders! she thought, and hated him afresh. Cold eyes that betrayed no emotion. How I should love to make him suffer!

She thought suddenly of Marcus, of warm, friendly, passionate eyes.

Oh, Marcus! Marcus! I want you. Of course it’s you I want.

“Carolan, what is wrong?” Esther was anxious. This morning when Margery had called to them to get up, Carolan had been so fast asleep that Esther had had to shake her to awaken her, and when Carolan did wake, her eyes were dark-ringed with sleeplessness.

“Wrong?” cried Carolan irritably.

“What should be wrong? Just everything… that is all! Do you enjoy this life of slavery?”

“But Carolan, today there is something more wrong than usual. Will you not confide in me?”

“Oh, Esther, how foolish you are! Nothing is any worse today than it was before. How could it be, when before it was as bad as possible?”

They stood at the sink, peeling potatoes. The dirty water ran up Carolan’s arms. Every time the kitchen door opened, she trembled with fear.

He would spring suddenly, she was sure. He would not come into the kitchen himself. Perhaps one of the roughest of his men would be sent to take her to the yard. They would tie her hands and feet to the triangle. He would not be there; he would not even bother to look on. There was no fire in him: he would coldly, calculatingly mete out what he considered justice. Crime Using mistress’s bath water, dressing up in mistress’s clothes. Punishment Fifty lashes. She imagined his keeping a little notebook, and writing such things in it. I would rather Jonathan Crew, she thought, than this cold, inhuman creature.

The morning wore on.

Margery said: “Are you in love, me lady? You’re as droopy as a sleep walker.”

“In love!” said Carolan, hatred shining in her eyes.

“Ha! Ha! In hate, eh?” said Margery, observant, shrewd.

“Not in love? Has one of the men been disrespectful to your little ladyship? Is that what makes you look so fierce?”

“I am not looking fierce. Why cannot you let me be!”

“Tut-tut! Give yourself airs with the men if you must, but not with Margery. Don’t forget there’s the whip over the mantel, put into me hands by Mr. Masterman himself.”

The whip! Mr. Masterman! Try as she might, she could not keep her lips from trembling.

“Come over here and watch the meat. Jin’ll finish them taties. Go on, Jin! And don’t you give me none of your sullen looks, me girl, or it will be the whip for you as sure as I’m Margery Green.”

Real sparks of anger were in her eyes now. She would show the girl that she could not cast those eyes of hers on Margery’s men. James had been mealy-mouthed enough last night.

“Why, look ye, Margy, d’ye think I want to take up with silly bits of gipsies! Not when I can get a bit of all right like you, girl!” Ready as you like, it came, and when a man’s tongue was so ready, could you trust him?

Margery’s fingers itched for the whip. She would have liked to lay it across the girl’s face. Very pretty she would look with a weal across her gipsy face! But Mr. Masterman would want to know what had happened, if Jin served at table with a face like that. Margery was afraid of Mr. Masterman. Queer, cold man, he was, so that you all but forgot he was a man. Funny how the very thought of him kept them in order down here. Jin was afraid of him; she would not like him to know she carried that knife around with her. Jin had cast glances in his direction, but he wore a thick mask through which the arrows of desire could not penetrate.

“Bah!” muttered Margery, contemptuous yet with a certain awe, ‘he’s only half a man!”

She let her hand rest on Carolan’s shoulder as the girl watched the spit. Lovely skin, like peaches warmed and touched with the sun. She had been washing her hair under the pump this morning, and the sun played about it, loving it you might say, making it more beautiful because it loved it so much.

In love? With which one? James, Tom, Charley? No! Don’t make me laugh; her haughty nose would go up in the air at the thought of any of them.

The kitchen door opened. Margery saw the girl’s face whiten. This was very strange; something was afoot… what? She sat very still her eyes downcast. Margery had never seen her so pale. Her eyelashes were incredibly long, and her pallor, oddly enough, make them look longer. They were tipped with reddish-brown. She was a beauty!

It was James at the door.

“Hot coffee at once! With biscuits. The lady has a visitor.”

Margery got up, grumbling.

“Morning visitors, I hates ‘em. Why does people have visitors in the mornings! All right, all right! Come on, you. You can help me. Not you, Jin … you get on with them taties, and keep your eye on the spit at the same time, will you?”

James went out. Margery touched Carolan’s arm.

“Look here, me girl. You can take their coffee up to ‘em. It ain’t often servants is allowed the run of the house, but you ain’t like the rest, see? It’s funny, but I don’t believe you had nothing to do with that thieving they sent you out for.”

“Oh … Margery …” Carolan caught the woman’s arm. She had great difficulty in keeping the teats back.

“Here! Here!” said Margery, herself moved unaccountably. She wished she was a man so that she could love the girl physically; Margery played with the idea while she made the coffee. It fascinated her.

“Now up you goes with it! Mrs. Masterman and her lady friend in the drawing-room. Steady, girl! For God’s sake don’t drop the tray, or it’ll be the last one you’ll carry into Mrs. Masterman’s drawing-room, I’m warning you. Now don’t be shy. Wouldn’t be surprised if Mrs. Masterman asked for you to wait at table. You’re a lot nicer to look at than that saucy Jin … Gipsies is dirty things, no mistake! Go on with you. Here’s the biscuit barrel. I’ll come up with you and knock. Ready?”

They mounted the stairs. Would he be there? wondered Carolan.

Margery knocked at the door of the drawing-room.

“Come in!” said Mrs. Masterman.

Margery pushed open the door, and Carolan went in. Mrs. Masterman was lying back in her chair, looking wan. She wore a fleecy jacket that made her look like an invalid.

Margery said from the door in a hoarse whisper: “Better pour it out for ‘em.”

Carolan, relieved that Mr. Masterman was not present, put down the tray and started to pour out.

“Bring it over here,” said Mrs. Masterman, and Carolan, her hands steady, carried over the tray. They helped themselves to brown sugar. There seemed to Carolan something slightly familiar about the dark-haired visitor.

The visitor said: “You seem to be well served, Mrs. Masterman. I must say I have the most shocking trouble with my servants.”

“Gunnar is so careful,” said Mrs. Masterman.

“Ah… yes. That is it. When you have a man to arrange your affairs …” Dark eyes studied Carolan appraisingly.

“I always think it is such a pity, when I see these young criminals.”

Carolan went out, wondering where she had heard that voice before. But that seemed a trivial matter. The main thing was where was the master, and what was he going to do about a rebellious and disrespectful convict servant who had behaved shamefully in his toilet-room? Had he forgotten? Was that possible? Wild hope soared up. A very busy man, was he not, with so much to attend to? Could it be that he had forgotten?

Something was happening in the kitchen. She heard Esther laugh. She had never noticed before that Esther had such joyous laughter. It came floating through the open door. Perhaps people’s voices were different when you dissociated them from their faces. If Newgate had left its stamp on Esther’s face, it had not been able to touch her voice. Margery spoke, excited, giggly. And then … another voice, a voice that made the blood rush into her head and beat like the tattooing of a jungle drum in her ears. The voice of Marcus.

She almost fell down the last steps to the kitchen. There he was, jaunty as ever, debonair, wearing riding breeches and leggings of leather, leaning in at the kitchen window.

She stood on the threshold of the room; he looked up and saw her, and she forgot the awful fear of punishment that was hanging over her, because the look in Marcus’s eyes dispelled all that.

He said: “Carolan!” and his voice was husky with emotion.

“Marcus!”

He held out his arms and she ran to him. He kissed her, first on one cheek, then on the other, then on the lips.

“My sweet, sweet Carolan.”

“Marcus … all this time … what has happened? Where have you been? You are free … Surely you are free? Oh, what happened? What happened, Marcus? Have you come to take me away?”

He laughed and held her from him.

“So much you want to know,” he said.

“So much I want to know. Why, your eyes are wet, my darling. Does the return of the wanderer mean so much to you then?”

Margery was laughing, holding her sides, while the tears ran out of her eyes.

“Come in! Come in! Mr. Masterman would be the first person in the world to want to show hospitality to the servant of his lady’s friend. Come in!”

“Servant… Marcus, you?”

He leaped over the window-sill. And Carolan was laughing now; they were all laughing.

“And you too, my haughty Carolan.”

“Poll!” cried Margery.

“Don’t stand there gaping, girl! Bring out glasses. A little drop of ale would go down well here, I’m thinking.”

Marcus put his arm lightly round Margery’s shoulder, and planted a light kiss on her hair.

“What angels have you fallen amongst, my darlings?”

“Go on with you!” Margery pushed him away.

“You keep your kisses for them as asks for them, young man!”

And she was laughing as she had not laughed for a long time. That was the charm of Marcus. His warm eyes embraced them all; Carolan first, Carolan his woman, then Esther, nice sweet Esther, and amorous old Margery, sullen Jin and even Poll standing there plucking her dress. Every one of them could feel the charm of Marcus.

The glasses were on the table. They sat round it. Esther was on one side of him, Carolan on the other. He put an arm round them both.

“Marcus,” said Carolan, ‘you must have been very lucky. Why … you seem not like a convict at all. You seem…”

“… A thorough gentleman! My luck held, my dears. I was taken into the service of a Miss Clementine Smith. She discovered I could manage a horse, so I drive her buggy; it is now standing in your yard.”

“You knew we were here, Marcus ?”

“Do you imagine I would not make it my business to find out where you were?”

“Marcus! I am so happy. If only I could go away with you! If only Esther and I. “If only! Do not forget we earn our rewards by good conduct.

One day …” She said: “I can wait now. I can bear anything. Esther, can you?”

“Yes,” said Esther, eyes shining.

“Yes, I can bear anything.”

“You are a pair of angels!”

“Drink up,” said Margery.

“It ain’t often I has guests in my kitchen, it ain’t!”

“That’s a pity, Ma’am, for it is right welcome you make them.”

Margery simpered and wriggled in her chair. Her eyes glistened. What a man! And he loved the girl. How he loved the girl! He was right for her. What had brought them out together? Imagine them … imagine them loving … And bless him, he had more smiles to give to Margery than to the dark-skinned gipsy. Dark-skinned gipsies were not to everybody’s taste!

Marcus told them what had happened to him.

“I went into the service of Miss Clementine Smith almost immediately. She had only just arrived in Sydney, and wanted a manservant. She said I was just the man for the job. I was lucky. I have been treated well.”

“Like a human being, I trust,” said Carolan, thinking of a pair of bleak, grey-green eyes.

like a human being exactly.”

“You are living near us?”

“In Sydney.”

“Oh, Marcus, it is over a month since we came here.”

“I know, I know. Do not forget I am not a man of leisure. I must wait on the pleasure of her who has taken me into her service. So when she arranges a visit to Mrs. Masterman, I can scarcely contain myself.”

“Oh, Marcus! Marcus! This is wonderful.”

“How much more wonderful it is to me! You look better Carolan, than when I last saw you.”

Old Margery said: “She had luck to be brought into this house. Mr. Masterman’s is the best house in Sydney, though I say it myself.”

“I am glad, Carolan,” said Marcus.

“I am glad, Esther. I don’t know how to thank the gods for placing my dear friends in such excellent hands, Ma’am.”

“What a caution!” giggled Margery.

“I don’t know what the Old Country’s coming to, when it starts transporting the gentry.”

“Your, smiles warm the cockles of my heart, Ma’am. May I come often to your kitchen?”

“What do you think this is, might I ask, a convicts’ club?”

“Just now it seems something like paradise to me!” Margery twirled the drink in her glass. The voice of him! The words of him! Never, in the course of a man-haunted life, had she known anyone like him. And the girl loved him too, and if she was not mistaken, so did Miss mealy-mouthed Esther! But what chance would she have, beside Carolan, bless the girl! That white skin, that red hair, those lashes tipped with reddish-brown. Margery shivered with ecstasy, which the mere thought of love between them could give her. If ever two was made for one another, she mused, it’s them! Come to her kitchen? He should come whenever he could; and they should have the basement bedroom to themselves any time of the day. And she herself would prepare a bit of something to eat and drink for them, for there was no denying that lovemaking could be hungry business… thirsty too! She chuckled, musing on memories that seemed suddenly touched with more romance, more beauty, in the presence of Marcus.