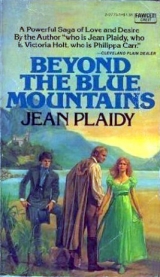

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“I have been blind,” she said.

“Blind!” She cried out: “Do not talk of me! Later I will tell you; but now I would hear of you. What brought you here? You stole nothing! You did no crime!”

“It is good of you to believe that, and even before I have said a word.”

“I am no fool!” said Carolan, and laughed inwardly at herself, for was she not the biggest, the most easily duped of all fools who had ever led themselves and others to destruction!

“I would like to tell you of myself,” said Esther.

“It is an ordinary enough little story, I fear. My father was a curate, and we were very, very poor. There were six of us. But he taught me, and when I was sixteen I was given a post as governess in the family of a squire… and the squire had a son.” She looked down at her hands, and Carolan was aware of the deep shame that beset her.

“He … made advances … which I could not accept, and that made him very angry. I did not know what to do, and I sought the protection of his parents. They did not believe me … and when the squire’s lady lost a valuable ring she accused me … and the ring was found in my room, and I was brought here. But I swear I knew nothing of the ring!”

“But did you not explain?”

The ring was found in my room.”

“She put it there that wicked mother of a wicked son! Oh, how I hate this world!”

“Whom the Lord loveth He chasreneth. We must bear our sufferings with fortitude. That is what my father used to say. They were sent us for a purpose. We must be meek, for it is the meek who inherit the earth.”

“That is a doctrine I will never accept. I will tell you something; I am going to marry a man who is a parson.”

“Oh!” Esther exclaimed with delight.

“I am glad … Carolan.”

“But,” said Carolan, ‘there are matters on which we cannot agree. I do not think we should accept our sufferings and the sufferings of others. Everard and I almost quarrelled about that. He said I was headstrong, illogical. He believes that people should be contented with their lot in life because that lot has fallen to them through God’s will. I do not! I never will!”

“Godliness,” said Esther, ‘is humility!”

“Then I’ll have none of it!” cried Carolan.

“When I think of what has happened to me … and my poor darling Mamma … and Millie there … and what has happened to you, I want to set faggots in this place, and pour oil on them, and I want to see this evil place go up in smoke. And yes … I would throw Jonathan Crew, who betrayed my father, into the flames … and with him your wicked squire’s son and his mother …”

“Ah, Carolan, you must not say such things, for truly it is the will of God that we are here.”

“Since you are obviously a saint, you had better steer clear of me.” said Carolan.

“I love the fire in you. It warms me. And I am so cold, so lonely and so frightened! I am wicked too, for I have had more comfort from your presence than from my prayers. There! That shows how wicked I am, does it not? Are you crying too? We must not cry, Carolan. This is our cross, and we must bear it. You see, I who have been so wretched, Carolan have had my prayers answered. I have now a friend, someone who talks to me, listens to me, who doesn’t laugh at me, who does not pinch me and kick me and scratch me, who gives me clothes to covet me.”

“Why did they take your clothes … all your clothes?” demanded Carolan. The others have some rags to cover them.”

“When I came in,” said Esther, ‘they cried at me, as they do to all, “Garnish!” I had no garnish. I had nothing … nothing but the clothes in which I stood. What could I do, therefore? They tore them from me as they did from your mother. But they left me my shift. And that night I knelt down and prayed, because my father has always said to me, “Never mind where you are, whatever you are doing, you must always kneel down and say your prayers.” I always had; and I did. And as I prayed they crept closer to me. Carolan, I am so feeble; I have no godliness in me, though I try to be good like my father. I knelt over there; you see, near the sill there. Through my closed lids I was aware of the flickering light from the whale oil lamp, and, Carolan, I tried so hard to go on with my prayers and not notice them. But I was afraid; I was more afraid than I had ever been before in the whole of my life. I could feel them creeping up to me; I did not know what they would do to me. I could smell their mingled breaths very close to me, and it was horrible, horrible, Carolan. You who are so brave could have no idea. Closer, they came; they were all round me; then one of them laughed. It was terrible laughter, Carolan. I trembled; I stopped praying; I covered my face with my hands, for I knew that the most terrible moment I had ever known was upon me. There I knelt in my shift, saying under my breath, as my father had taught me, “Courage, O Lord; give me courage!” Then they started.” She stopped, and covered her face with her hands; she began to sob.

“Silence there.” snarled a drunken voice in the darkness.

Carolan whispered: “Don’t cry. Don’t think of it telling it brings it back.”

“But I want to talk to you. I have talked to no one for weeks, and the silence is more than I can bear. I must tell you what I had to suffer here; I must make you understand why I could not be brave. I did not kneel again, after that night. I prayed silently. You see. Carolan. I denied my God. That’s why He had forgotten me.”

Carolan said: “When I was little, my half-sister and I used to go to the curate for Bible lessons; he was the curate to the father of the man I am going to marry. I never listened to those lessons; my cousin Margaret did though.”

“Poor Carolan, then you have been denied the comfort of God.”

“I.” said Carolan, ‘would rather rely on the comfort of my own ability to stand up to these beasts! Tell me more, if it does not distress you too much.”

They jeered at me, Carolan. That was not all; they … took my shift, and when I stood before them in terrible shame, they laughed at me. They touched me, Carolan … they did obscene things to me, Carolan. They said things that were coarse and horrible; I cannot talk of them; I cannot tell you. And next night I… did not kneel and pray. They would not give me any clothes to cover me. I have found pieces of old rag and tied them about me, and worn them for a day or so … perhaps longer … until they notice and remember, and then the rags have been torn off me…”

“If you have been here a month, you cannot surely stay much longer. You will have to stand for trial surely.”

“Some day, I suppose; I do not know when.”

“How can people be so cruel, one to another? Do you know?”

“I do not, Carolan. But I believe that when life gets too bad something happens to help you along. Today I had felt so weary, so tired, so cold, so hungry; and I have thought of the winter coming on, and I have said to myself: “I cannot bear it. If I could find some means of ending my life, how gladly would I take it!” And then, just as I thought these wicked thoughts, the door opened and you came in, and your courage and the way you held your head made me ashamed of myself.”

Carolan said: “There must be some way of getting a message to my friends!”

“You need money. All the time in Newgate you need money. They say that a stay in Newgate is not too unpleasant if you have money. Money will buy you a separate room, food, coals, candles. Without money you get your pennyworth of bread each day, and water from the pump to drink. That is how things are here on the Common Side.”

“Something will be done!” said Carolan.

“I will see to it. Somehow I will get a message out. Why … there is Everard! He will surely come for me. There is the squire; when he hears where I am, he will not tolerate that for a day. He has money; he has influence; and so has Everard. They will come for me. I know they will! And listen, Esther. This I swear. I will not leave this place unless you come with me. You are innocent, more innocent than I, for I was a fool, and folly must be paid for. I shall not let them keep you here…!”

Carolan broke off. Esther was kneeling now, with her eyes tightly shut, and the palms of her hands pressed together. Through her closed lids tears trickled down her cheeks. Her lips were moving.

“I thank thee, O Lord!” And Carolan knew that till the end of her days she would remember that scene, the sleeping bodies around her, the wail of a hungry child, the dismal gloom, the hateful stench … and the kneeling girl, offering thanks to her God.

Carolan could not define her feelings; she was too worn out to cry; she was angry; she was moved; she was full of exaltation, for she was going to help this Esther, as a little while ago she had planned to help her parents; she was, too, full of sorrow and misgivings.

Esther’s hands fell to her sides; her face, in the light from the lamp, looked radiant.

“How old are you, Esther?” asked Carolan.

“Sixteen.”

“My poor child!” said Carolan.

“I am seventeen.”

“We are much of an age then,” said Esther shyly.

“Yes, but I am older. I am going to try to sleep now. Can you?”

“May I stay near you?”

“Of course. You will join us now, Esther, will you not? We are all friends?”

Esther settled down beside them, and both girls lay for a long time, eyes open, staring at the grim walls enclosing them.

“Esther,” said Carolan, ‘you must not cry so much.”

“No. I have not cried so much until tonight.”

“You must not cry! You must not cry!” said Carolan, and silently wept.

Morning came, exposing fresh horrors. Now it was possible to see more clearly, the depraved faces of those about her. Carolan kept thinking: I shall wake up. We went to the play last night. This is a nightmare. I shall wake up in my bed.

But she could not go on indefinitely thinking it was a dream. Soon that other life, the serene, happy, free life would seem the dream, and this horror the reality.

Kitty was sick that morning, and the irons cut into her flesh; she cried with the pain. She was not sure where they were yet, and Carolan was glad of this.

“Carolan, how my back hurts! It’s bruised. This bed is so hard. Carolan, where are we? There is something horrible near me… something dead; I smell it.”

Carolan sent Millie for water, and Millie got it … with Esther’s help. Kitty drank, and Carolan bathed her face and then Kitty fell into a deep but troubled sleep.

“She will recover.” said Esther.

“She is healthy … that much I see. She has had enough to eat; it is those who come in starving, who are quickly starved to death. I wish we could loosen those irons; they are too tight. See how the flesh is swollen…”

“What can I do about that?” demanded Carolan.

“Cannot the irons be taken off? There is no fear of Mamma’s trying to escape.”

“They could be bought off… all save one.” An assistant keeper came in; he was carrying ale and bread which he had bought for a prisoner who had had a little money sent in to her.

Carolan went to him.

“My mother’s irons must be removed. Otherwise I fear there will be trouble.”

Bleary eyes studied her. Her clothes were good.

“One set “as to remain,” said the man, ‘but…”

“Money, I suppose!” said Carolan. Then I have none. You will do this for the sake of decency!”

He chortled.

“Decency, eh?” He scratched his head.

“Now I can’t say as how I’ve heard of irons being struck off for decency. Money’s the only thing that’ll strike off irons, my lady. And then the one must be left. Fair’s fair… that’s what we say in Newgate. One pair has to stay on.”

“I will get money… somewhere!” said Carolan.

But the man was no longer interested; he had passed on.

“I cannot endure this!” cried Carolan, returning to her mother.

“She still sleeps,” said Esther.

“And look. She is smiling in her sleep. That means good dreams.”

Carolan said angrily: “I will not stay here! I will get out! But shall I? How do I know? Everything I have done since I have been in this accursed city has made trouble. I am more likely to lead you into trouble than get you out of it. Millie! Why don’t you reproach me? I brought you into this. You… my mother… my father… myself I It was my folly. I do not think I shall ever get out. I shall stay here for the rest of my days … for I am a fool… a crazy fool who not only brings trouble on herself, but on all those around her!”

Millie stared, open-mouthed. Esther sought to comfort her, and Esther could do that, for when Carolan looked through her tears at the sweet face of the girl, so pale and thin, she wondered how she could speak of her misfortune when before her was the greater one of Esther.

The day began to wear on. Now the door was unlocked, and the prisoners had the use of one of the yards. The scene was more sordid by daylight than it had been by the light of the whale-oil lamps. The faces of the women were more clearly seen, and in consequence more horrible. But already Carolan was not feeling the horror of the place so acutely; her eyes had grown accustomed to the sight of vermin; her, ears to the obscenity of the conversation in which these creatures seemed to find some relief from their misery; she did not feel now that the smell of the place would make net retch. She had learned that the feeling one may have for a fellow being is in some strange way a more precious thing than it would otherwise have been, if that friendship is nurtured in misery shared. She was drawn to Esther more than she had ever been drawn to anyone in so short a time. Esther was so weak, and that pioneer spirit in Carolan, that leadership which was so essentially a part of her character, was stimulated.

Carolan found that she could not eat the bread that was given her. Esther ate hers ravenously; so did Millie. Millie was like an animal, adaptable, accepting the cruelty of life as her natural due.

“You must eat,” said Esther.

“I cannot!” said Carolan.

“It is filthy stuff.”

“It is all we shall get. Only those who have money can eat better food.”

“I would rather starve than eat that.”

“Save it,” said Esther.

“You will be glad of it later.”

“It will be crawling with maggots by that time. You and Millie eat it between you.”

Millie’s eyes glistened hungrily; Esther tried to prevent hers from doing the same; and Carolan broke the loaf in two and gave them half each. She felt rather sick to see the eagerness with which they consumed the mouldy stuff.

Kitty stirred. She murmured, “Carolan, is that you? Don’t draw the curtains … How my head aches! I will have my chocolate now.”

Carolan bent over her.

“Mamma… you are not at home now.”

Kitty opened her eyes very wide. Memory came back. She tried to raise herself.

“Carolan, what is this…? Why, Carolan…”

Kitty had raised her head and was looking about her.

“Oh…” she said.

“I… remember…”

“We are in Newgate, Mamma. You remember what happened last night?”

“Darrell…” said Kitty, and began to cry.

“Mamma, Mamma, you must have courage. We will get out of here. Then we will avenge him! I will get a message out to Everard and … the squire… We shall get out, never fear!”

Kitty said: “My darling, of course we shall get out. But … your father … Oh; Carolan, I cannot bear it! I cannot bear it! That man … that vile beast… and I thought … it was my folly…”

“Listen, Mamma! We were foolish, all of us. We are paving for our folly now. Let us not look back. My father would not have wanted us to do that.”

There was no comforting Kitty. She wept bitterly and her sorrow was great, for she did not even notice that her clothes were torn and her body bruised, though now and then her hand as though unconsciously, strayed down to where the irons cut into her flesh.

Esther whispered: “Poor, lovely lady! How unhappy she is! And you see, her sorrow for her husband wipes out all other pain. She does not feel her own sickness; she does not feel the pain that iron is giving her; she only feels one sorrow, and that is the loss of her husband. That is proof of the goodness of God.”

Carolan, sick with grief like a wounded animal, spoke sharply to the girl.

“Do not talk to me of God. What have any one of us done that we should suffer in this way! That is what I should like to know!”

“Hush!” said Esther.

“Oh, hush!” And she looked so calm, so serene, that it was Carolan’s turn to be comforted. Carolan had physical strength; Esther had spiritual strength. They could lean on each other; they had much to give, and much to take.

With the passing of the day their spirits rose a little. Kitty’s natural optimism was fighting its way to the surface. This, she said, was not the sort of thing that could happen to people like them. What had they done to deserve it? The thing to do was to get a message through to Squire Haredon and Everard Orland. She tried to walk out into the yard with the young people, but she walked painfully and each step made the irons cut more severely into her leg. She was horrified at the discoloration which was already beginning to show itself.

“They must be removed at once,” she said.

“As soon as we can get some money they shall be,” Carolan assured her.

Kitty pointed out her grievance to one of the guards, showing him her swollen ankle. Queer, thought Carolan, how naturally the role of coquette came to Kitty; she would play it even in her moments of direst misery. But the man was dour; he shook his head. Irons could be bought off; he had never heard of them coming off for any other reason. Kitty was shocked at the refusal of her request, but the man’s indifference acted like a douche of cold water in her face. She brightened. Of course, she was looking frightful! Carolan seemed to see her reasoning to herself… Her cloak was torn, her skin scratched, her hair .. oh, her beautiful hair! These things could be remedied… and when had Kitty ever failed to get what she wanted from mankind? Carolan’s heart was filled with pity for this poor foolish Mamma.

During the second day a turnkey came into the prison room and called: “Haredon! Who is Haredon here?”

Carolan started to her feet.

“Carolan Haredon,” he said.

“Are you the one?”

“I am,” said Carolan.

“Then you had better come with me.”

“Why?” said Carolan.

The turnkey shrugged his shoulders.

“Orders was to bring you; not to tell what you’re wanted for.”

“Suppose I refuse to go!” cried Carolan, incensed by the cruel eyes of the man, and of all these men who found amusement in the torture, both mental and physical, of their fellow beings.

Esther caught at Carolan’s hand; Esther’s eyes were pleading with her. Never would she make this hot-headed, courageous, magnificent friend of hers understand that when you are helpless arrogance is a mistake.

The turnkey scratched his head.

“Orders has to be obeyed,” he said.

“Come on!”

Kitty began to cry softly. Millie stared open-mouthed; Esther’s lips were moving in silent prayer, Carolan turned to look at them; they thought something more fearful than what had gone before was about to happen to her. A flogging perhaps. Carolan’s courage began to quail.

“Who gave these orders?” she demanded in a loud, blustering voice, hoping that she was hiding her terror from her friends.

“Come along with you!” said the turnkey roughly, and would have laid hands on her, but she said, suddenly subdued: “Very well. Lead the way.”

Eyes followed her as she went through the room, watchful, speculative, excited eyes.

She was led through corridors, up steps and down again. She would never forget the mental suffering she endured on that walk! She could feel the lash about her shoulders. She had heard the prisoners say that blood sometimes came at the third lash … and that as the lashes went on, the victims fainted, and often when they did, the lashes were suspended until consciousness was regained.

The turnkey paused before a door. He hesitated; his little eyes looked full into her face; the corners of his lecherous mouth twitched as though he found it difficult to control his laughter; he was enjoying himself; he knew something of what her thoughts had been as he led her slowly through those dark corridors.

He threw open the door. Beyond him was a small room, and in it was a table, and on the table food was laid out; there was wine and cold roast chicken. That much she saw, and the sight of food made her dizzy. But a man had risen from the table; he was coming towards her. He took her hands, and said: “Carolan, my darling! What have they done to you?”

The turnkey snickered as he closed the door. She was alone with Marcus.

Marcus had not changed in the least; he kissed her hands.

“I heard, only an hour ago, that you were here,” he said.

“I hear the news, you know! And when I heard I sent out for this, and I sent for you to be my guest.”

“Marcus!” she said.

“Marcus!”

“No,” he said, ‘not Marcus now. William Henry Jedborough, who was sent to Botany Bay for fourteen years, and came back Marcus Markham after three. And now here is William Henry again… your friend who hopes to make your stay in Newgate a little more agreeable than it has hitherto been.”

“Marcus… who are you?”

“Not Marcus, darling. I always hated the name. William William Henry, a thief and a rogue, an escaped convict. Here I am … awaiting the death penalty.”

“The death penalty!”

“Ah! You grow pale at the thought. It is worth being sentenced to death to know you care so much.”

“You are the same. Such foolish, extravagant words!

“And you are the same. So quick to anger, and no attempt made to hide it… even from a poor man who is to be condemned to the gallows!”

“You joke about it.”

“Is it not a matter for joking? Let me whisper to you, Carolan the gallows are not going to get me!”

“How will you prevent it? You seem to have much power, Marcus.”

“William, darling… William Henry.

“I have thought of you as Marcus.”

“Then call me Marcus. It will always remind me that when I went abruptly from your life you thought of me.”

“Do you imagine one forgets one’s Wends and never thinks of them when they have gone out of one’s life ?”

“My sweet Carolan!”

“Please tell me what happened to you.”

“What is there to tell, my sweet? I came to meet you, as we arranged, and the man Crew met me at the corner of the street. He had his van and his accomplices waiting for me.”

“Did you think I had betrayed you?”

“I knew you had betrayed me.”

“How you must hate me.”

“On the contrary, my sweet Carolan, I love you.

“How foolish I have been! I brought it on us all.”

“You have never been anything but adorable.”

“Do not talk so foolishly. I brought him to the shop the very first day I came home. I betrayed my father and you… and now my father is dead, and you are about to die …”

She covered her face with her hands, and he lifted her in his arms and carried her to the table. He sat down on one of the wooden chairs, still holding her. He wiped her eyes tenderly.

“He would have got us, darling, sooner or later. He was waiting, you see. He knew I was a thief, but he wanted the highest ransom for me. He was waiting till I “weighed my 40”. As for your father, he would have got him too. No! It is you, my sweet Carolan, who have been so wronged; you who do not belong here. Look, Carolan, we must discuss what is to be done. First of all let us eat, for I hear you have been in this filthy place for two long days, and I know you must be hungry. See! I sent out for this chicken, it is tasty. And the wine is good. Now, child, we will eat together and we will talk.”

“I am bewildered,” she said.

“You have such power … you, a condemned man!”

“Certainly I have power. I have my business associates outside Newgate. I have money! Money is power: it buys me this room; it buys me this food. It buys me your company … There is not so much to fear from law and order when you have money, Carolan.”

“I cannot sit here and eat with you,” she said, her eyes on the chicken. How good it looked! Golden brown! How hungry she was … faint and sick with hunger!

“Did you not hear that my mother is in Newgate with me ?”

“I did hear. We will send for her.”

“She could not walk here… the irons …”

“They shall be struck off, my dear. Yours too. All but the one pair, and that is not so hard to bear when you have had to drag three about with you. Your mother shall come and share our meal.”

“I don’t know how to thank you. It is noble of you, when it was I who

…”

“Hush! There is nothing noble about me. Did you not know that? I will see to it that your mother’s irons are struck off. and that she is brought here at once.”

There is Millie too. And Esther… They must all come, or you must give me that chicken and I will take it back and eat it with them.”

“Hal You would be torn to pieces if you went back with that chicken!”

“II Indeed I should not! I can defend myself.”

“That you can, I swear! Oh, Carolan, Carolan, how I love you, Carolan!”

“This is not the time to talk of love! Nor do I admire your light treatment of the subject.”

“How like you! I offer you release from discomfort or comparative release from it and all you offer me in exchange are harshness and cold words.”

“I do not mean to be cold, Marcus … but your flippancy seems out of place.”

“I never felt less flippant in my life. Do you know the thought of your being here makes me burn with rage. You believe that, Carolan?”

“Oh, remember my own folly has brought me here. Please will you have the irons struck off my mother … and could you do the same for Millie and for Esther…?”

“Esther?”

“A poor girl who has become a friend of mine.”

“What! Making friends so soon?”

“If you could see her you would like her. She is innocent, and her case is far more to be deplored than my own.”

“How I adore you, Carolan, for your anger and your enthusiasms, for your harshness and your kindness!”

“Then please make haste, for every moment spent in those irons is torment for my poor mother … and Millie and Esther are so hungry! But… can you do these things?”

“You shall witness the power of money, darling. But first we will have those irons off yourself, for it makes me very angry to see you fettered, Carolan.”

He went to the door. The turnkey appeared immediately. He must have been waiting there, thought Carolan, speculating on further opportunities of earning money.

In a short while all but one pair of irons were struck off Carolan.

“There!” said Marcus.

“You see my power, Miss Carolan! I am a magician … the magician of Newgate. I wave my wand ..” in this case it is coin… and it is as I say!”

“But Marcus …”

“Perhaps you had better call me William, for Marcus was a flippant fellow, never very much to you, your thoughts being all of a certain parson. But William is a different kettle of fish. He came into your life when the parson had left it…”

“How foolishly you talk!”

“No, Carolan! Do you think your parson will marry a wife who has been the guest of Newgate?”

“What difference does that make?”

“A hell of a difference, sweet Carolan, to a parson!”

“Rubbish!”

“Sound sense, sweetheart.”

“Please do not call me by those endearing names. I find it excessively irritating. I want to know … is it true that you are condemned to die?”

“The fate of all who escape from Botany Bay to be caught again generally.”

“You joke about it!”

“I can afford to, Carolan. It shall not happen to me, I promise you; or I should be very surprised if it did. You see, I have money, and money can buy almost anything a man can desire. It can buy love; it can buy life.”

“I do not agree with you.”

“Of course you do not. You would not be Carolan, whom I love, if you did. But, bless you my child, one day you will learn I am right. Not, I grant you, that it can buy these things in full measure. I can buy my life, but I doubt if I can buy my liberty. And as for buying love … let us not talk of it though, for I see the subject distresses you.”

“Do you think it will be long before the others can come to us ?”

“It will be done as quickly as money can do it.”

“You talk incessantly of money!” She must keep the conversation going somehow, and she averted her eyes from that table, for there was in her a wild longing to sit down and fall upon the food laid out there.

“Naturally! Money, money, money! One thinks of little else in Newgate. Now on my last visit I had no money. That, I said at the time, shall never again happen to me. Here, darling, eat one of these bread rolls while we await the others.”

She said faintly: “I would rather await Their coming. Will they be much longer?”

His eyes glistened, she saw; they were very tender. She was suddenly aware of what an unkempt spectacle she must present to those eyes. She touched her hair.

“What would I not give for a tub of warm water and a change of clothes!” she sighed.

“I wonder you recognize me.”

“I would recognize you, Carolan, whatever the disguise! But do not think of it. Let us sit down and eat while we await the others.”

“I said I would rather wait. The food would choke me when I thought of them in that foul place.”

“You are too sentimental, Carolan. Sentiment is well enough in its rightful place; but never let it stand in the way of common sense. Come, my child!”

There was a tap at the door which flew open without any response from Marcus. Eagerly she turned, but it was not those for whom she had hoped, but two turnkeys with more food which they set out on the table.

Carolan stared at the table.

“Come!” said Marcus.

“These little rye cakes are appetizing.”

He held one out to her; she could not resist it. She seized it and ate it ravenously. He watched her, well pleased. Then he went to her suddenly and seized her by the shoulders.

“Carolan! Carolan! I don’t despair,” he said.

“What do you mean?” she demanded, her mouth full.

“You are so sweetly human, but you were ever one to set yourself impossible tasks. And how I love you when you fail!”

“You talk the most arrant nonsense.”

“Do II Well, now I shall do something useful. I will carve the chicken.”

She watched. She felt faint with hunger. She ran to his side, and he, the carvers poised, looked over his shoulder and smiled mockingly into her eyes. He cut off a piece of the breast and put it into her mouth. Never had food tasted so good.

“More!” he said, and continued to feed her. And as she ate he laughed and kept murmuring her name.