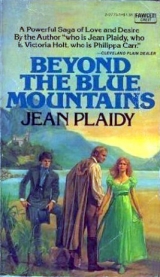

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

He approached.

“By gad!” he drawled.

“By gad…”

Flash Jane tittered. One of the women began to sing in order to call attention to herself.

“Silence, you old whore!” cried the Marine.

Carolan watched the eyeglass turn on one woman, then on another. It was getting nearer to her and to Esther. She gripped Esther’s hand; Esther cowered close. The indignity of it! The humiliation! Hot colour flamed into Carolan’s face; the eyeglass was approaching her; instinctively she knew that when it reached her it would pause.

Another man had appeared. He was very fair and very large, with big, irregular features. The captain was with him, and from the respectful attention the captain was giving him it appeared that he was a person of some importance. His mouth was a straight line; he looked as if he could be excessively cruel, coldly cruel. Carolan was alert now. Neither she nor Esther must fall into the hands of the man with the eyeglass.In her panic, Carolan told herself that anything would be preferable to that. She began to bargain, which was the only way of prayer she knew: “Please let the other one see us. Do not let that eyeglass find us. If You will only not let that happen, I will… I will… try to believe in You: I will try…”

This way, Mr. Masterman,” the captain was saying. This way, sir. They freshen up, sir. Soap and water will work wonders, sir. A cargo always looks very frowsy on arrival; it’s the conditions aboard.”

“Frowsy is a very mild way of expressing it,” said the man who had been addressed as Mr. Masterman. His tone was cold; his words clipped. The eyeglass was very neat now.

“Hello, ladies.”

The little girl began to scream suddenly.

“I won’t go up a chimley! I won’t! I won’t! I’ll jump in the sea. I won’t be burned to death!”

Mr. Masterman and the captain had paused. They stared at the child who had thrown herself down on the deck and was sobbing wildly.

The Marine kicked her.

“Get up, you baggage! You ugly imp, get up!”

She did not move and he kicked her again.

“Get up, I say! Get up!”

“What is it that the child says?” inquired Mr. Masterman.

“It is giving themselves airs, sir, to call attention to themselves. A taste of the lash will do her good.”

The man with the eyeglass stared down at the child.

“Ugly little devil. Cripple, ain’t she?”

Carolan stepped forward unthinkingly.

“She has been badly frightened. She was nearly burned to death.”

They were all looking at Carolan now. The man with the eyeglass quizzed her with insolent interest.The captain’s face was scarlet; so was that of the Marine.

“Get back into your place. Speak when you are spoken to.” He turned to Masterman. These convicts have no shame, sir. They push themselves forward to get attention.”

“Bless me!” said the man with the eyeglass. He rocked backwards and forwards on his heels.

“I believe it is a redhead. And Dammed, I do declare a little soap and water would make a beauty of the gal!”

Carolan was limp with terror. Impulsively, foolishly, she had done that which she had most longed to avoid; she had called attention to herself. She remembered some of the stories she had heard of prisoners who were taken into households; she guessed the fate of anyone taken into the household of a man such as this one.

It was one of the important moments of her life, and she knew it. She was aware of everything about her, the rocking ship, the changing sea and sky, the bright plumage of birds, the green lush land before her. Perhaps she forgot her cynicism and prayed then, humbly: she did not know; all she was aware of afterwards was that some instinct made her turn her head towards Mr. Masterman, to hold him with her burning eyes, to beg, to plead.

“Save me!” said her eyes. And then as though from a long way off she heard his voice.

“My wife wants a couple to work in the kitchen. She looks a strong girl, that one.”

Carolan thought she was going to faint. The smell of filthy bodies in that fresh air enveloped her. Desperately she fought her faintness. She took an almost imperceptible step forward, and she was dragging Esther with her.

Those queer grey eyes withdrew their gaze. It seemed like minutes before he spoke, but actually it was only a second or two. He said: “Those two look all right. Those are the two I will take.”

The man with the eyeglass dropped it. Carolan heard his exclamation “Gad, sir! I saw the girl first. By gad, Mr. Masterman …” But there was defeat in his voice, which told her that Mr. Masterman was an important person in the new land for which they were bound.

When Carolan and Esther went to Sydney it was little more than a settlement, for several years were to elapse before Lachlan Macquarie with the help of a transported architect, was to replace its wood, wattle and daub with stone and brick, and straighten out in some measure the confused crookedness of its streets. The house into which Carolan and Esther were taken was one of the grandest in Sydney, standing on the corner of an up-hill road that branched out of Sergeant-Major’s Row, now George Street, and which was little more than a track which drivers of carts had followed among the low hills. From the upper part of the house it was possible to get a perfect view of what has been called the most beautiful harbour in the world, with its sand and gravel beaches, and its many indentations fringed with green foliage. When Carolan had first seen it, having been sent to clean the attics, she was lost in admiration for so much that was beautiful; and then in one of the narrow, winding, up-hill roads she saw the bent backs and manacled limbs of a chain gang returning from work, and went quickly from the window, wondering if it were possible that one of those scarcely human creatures was Marcus. She had been lucky, she and Esther. So much that was horrible might have happened to them, but they had had the good fortune to be taken into Gunnar Masterman’s house; this man was a leading citizen with his eye on big rewards for the services he rendered the youthful town; a cold and calculating man by all accounts, but a wise and good man who went to church every Sunday. Upright, commanding, excessively virtuous, he was friendly with Governor Philip Gidley King; he had married the daughter of Major Gregory, a man of wealth and power in the town, and it was a worthy marriage, for everything Gunnar Masterman did was apparently worthy.

Being confined to the basement, it was only rarely that Carolan saw the upper part of the house. The servants were kept to the basement as much as possible, for they were convicts, all except Margery the cook, and she was on ticket of leave. Their bedroom a huge room which every one of them shared was in the basement. Its floor was of earth, and one of its walls was the side of the hill against which the house had been built. There was a small grating high in one wall; and this place was considered adequate, even luxurious, accommodation for convicts.

It was at the end of January when they arrived, and in the next weeks the summer weather grew intolerable. The mosquitoes were a plague to torture English skins, and there were no sleeping nets available in the basement. The moist heat was intense and oppressive; there was no respite. It was too hot to work by day; it was too hot to sleep at night.

Esther, who was adaptable, was almost happy, but Carolan rebelled against this new life, and as the memory of Newgate and the convict ship became more and more remote, her dissatisfaction grew greater.

But Margery, the priestess of the kitchen, the ticket of leave woman, was drawn more towards Carolan than towards Esther. Margery had been sentenced to seven years transportation for bigamy, and had served four years of her sentence in Mr. Masterman’s establishment when she had been given a ticket of leave and put in charge of the convict servants. Having just come into freedom she was ostentatiously aware of it. She flaunted that freedom; she boasted of it; and she was witheringly contemptuous of those who had not yet attained it. She wore blue merino, and when she worked in the kitchen, a white apron over it; she smoothed it happily, contrasting it with the yellow garments the others wore. She was not unkind, but lazy and selfish, sensual and mischievous. Her most precious possessions were her memories and the bunch of keys she wore at her waist, these latter the symbols of freedom. She talked incessantly of her past, and Carolan soon learned that she had begun by being the wife of a small tradesman; he was a good man, but he did not satisfy her for long, and she ran away with a travelling actor who deserted her after three months, when she took up with a pedlar. She loved all men; she couldn’t help it, she told them; there was something about men that appealed to her. They were so strong, and yet such babies. She loved them all. from Mr. Masterman to James who did odd jobs about the house. And the pedlar had been a proper man with whom life had had its ups and downs but had managed to be excellent fun. She had travelled everywhere with him; he had said she was a wonderful woman at getting the men and girls to buy their goods, and so she was. She could sell anything … particularly to men. But the pedlar was a jealous man, and once he had seen her trying to sell a book to a farmer behind a water-butt, and he had been so angry, poor, sweet man, that he had walked off and left her. The farmer had a wife, and would have none of her either; so she had wandered on and on until she came to a cottage, and in this cottage lived a curate all alone, and she had stayed with him; and the poor soul had had but one bed which he had wanted to give up to her, but she would not have that; so they shared the bed, and he, poor religious man, had wanted to marry her after that, fearing he might be damned if he did not. She had had to soothe his poor worried mind, and that was how she committed bigamy and came at last to be a ticket of leave woman in Mr. Masterman’s kitchen. She had taken James, the odd-job man, for her friend now. He used to lean on the kitchen-sill and she would feed him with tit-bits. She was proud of her friendship with James, for he was a free man… free enough in this town of convicts, that was on ticket of leave like herself. Mr. Masterman trusted James. He went about the place as he liked; sometimes he rode out to one of Me Masternan’s stations and worked there for a week or two. At midnight he used to knock at the basement bedroom door, and Margery would let him in; they would whisper together, keeping up a pretence that the others did not hear, nor even guess at these midnight visits of James’s.

Margery, who liked to talk of her own life, had a curiosity about the lives of others.

“What brought you here?” she demanded of Carolan and Esther.

Carolan told her.

“H’m!” said Margery.

“I don’t know as I like thieves in me kitchen.”

“We were wrongly accused,” protested Carolan.

“We are not thieves!”

Margery and Jin, the parlourmaid, rocked with laughter.

“All convicts are accused wrong … according to them,” explained Margery.

“I can’t think what Mr. Masterman can be thinking of to bring thieves into me kitchen!”

“Look here!” Carolan said hotly.

“I never stole anything. If you think I did, if you think I’m not good enough to mix with you… I… I… I’ll ask to be moved right away.”

Margery put her hands on fat hips and rolled about in delight.

“Hark to her! Hark to her! Now who do you think you are, my dear? The Queen of England? The Princess of Wales? Just hark at her. She will ask to be moved. And listen to her, Jin; just listen, girl! The way she talks… all haughty, eh?” She turned to Esther.

“And what about you?”

“I know it is of no use to say so,” said Esther, ‘but I am innocent too.”

Margery seemed overcome with merriment and at length gasped out: “I ain’t laughed so much since my curate put his I spectacles on his nose and said “Well, if you really think I ought to come in with you … I will. Perhaps if we pray for great strength of mind…” No, I ain’t laughed so much since then!”

It was Carolan she liked though. Not Esther. Mealy mouthed, that was Esther. Carolan, she fondly supposed, was something of what she herself had been at that age.

“Thieving was something I never could abide,” she said.

“I

wouldn’t have thought you would have been sent out for thieving; you don’t look the kind. Still, you are here now and I don’t mind telling you you are the dead spit of what I was at your age. I was married then though; we had our little shop. There I was. ladling out the sugar; we used to make love behind the sacks of flour. Funny it was when customers come in. I can laugh at it now. Look here, you see that whip hanging over the mantel? That’s for them that can’t do as I say, do you see? Do you see?” she asked Esther.

She looked with disfavour on Esther. Thin! Lovely hair though. Not one for the men. and the men wouldn’t be for her either, because men were for those who liked them, and she didn’t blame them for that!

Jin, the parlourmaid, was a good-looking girl of the gipsy type. She had flashing black eyes and vital, black, curling hair; in her ears she wore brass earrings, and she had tied a piece of string about the waist of her yellow frock to accentuate the smallness of her waist and the line of the bosom above.

“Now Jin here,” said Margery, and her voice took on a note almost of reverence as she spoke, “Jin was transported for attempted murder. She stabbed her lover. Mind you, I wouldn’t say but what he deserved it; he was carrying on with somebody else right under her very nose, so she stabbed him. Now I was never a one for violence myself and a good deal I had to put up with particularly from my pedlar! He would go take his pack into a house, and, given half a chance, he’d take advantage of the lady of the house in the twinkling of an eye and scarce say thank you. There was a man to take up with, and mad he could make me, but I trust I’m a woman who can control herself. Still. I understand Jin.”

Jin eyed both Carolan and Esther from under lowered brows. She was sullen, not inclined to be friendly.

“Jin’s got a mighty temper, she has!” chuckled Margery.

“Show ‘em what you carries around with you, Jin!”

Jin did not answer, and Margery pulled at her skirt and chuckled throatily.

“Where do you keep it today, Jin? In your pocket, eh? There it is; take a look at it. She carries that knife around with her. and she’d as like bring it out as look at you. That’s what gipsy blood does for you. I know. I knew a gipsy once; he come to out door, a fine-looking man, flash as they made “em. Baskets he had for sale, and he asked me to cross his hand with silver.

“Lady,” he says, “there’s a dark man coming into your life. You are going to be glad of this dark man, lady!” And believe me, I was … curate’s being a bit tame now and then. Talk about temper, he’d got one. They was encamped near the cottage for days. I saw a lot of him. And his wife carried a knife around, just like Jin. You’ve got to keep clear of people what carries knives. I’m not so sure of what Mr. Masterman mightn’t say if he was to know you carried that knife around.”

“I ain’t hurting no one,” muttered Jin.

“It’s my knife, ain’t it?”

“No!” said Margery.

“It ain’t. It’s Mr. Masterman’s. Everything here is Mr. Masterman’s. You and Poll and these two here. Why, if he liked…”

“I did not know,” said Carolan, ‘that he had bought us body and soul.”

Margery rocked backwards and forwards, laughing.

“Don’t it make you laugh, Jin? The way she talks, eh? Body and soul! Tell you who she reminds me of? The mistress. Talks just like that, the mistress does. And every time I looks at the -poor lady I says to myself: “Poor Mr. Masterman!” You would think … but there you are, men is funny creatures, no mistake. Well Miss, do you think we’re going to suit your ladyship here? Speak up, lady. We’ve got to suit you, haven’t we; now whether you was to suit us, that ain’t no importance at all, it ain’t!”

“Well,” said Carolan, ‘you asked for my opinion; I have given it.”

“I say, Jin, I do like to hear her talk. You’d think she was out for politics, not thieving. Here, you! Why don’t you say something?”

“What do you want me to say?” asked Esther.

“How do you like us?”

“I… I think I am going to like it here.”

“This is good, this is! A pair of “em! Now my curate, he spoke soft and gentle just like her… but soft and gentle, rough as you like, they’re all the same between the sheets. That’s men for you! Women’s the same, I bet! Where’s Poll? Poll! Polly! Come here and meet your new friends.”

Poll came from the sink, wiping her hands. She was very thin and pale and ugly; her nose was large, her eyes small, and her mouth was crooked; her teeth were uneven and brown.

“Poor Poll,” said Margery.

“She come from the workhouse and was took advantage of. She murdered her baby; that’s why she’s here.”

Poll started to cry.

“Now, don’t snivel, Poll,” said Margery sharply.

“And it was your own fault for getting took advantage of. Come here and meet her ladyship. What do we call your ladyship, eh?”

“My name is Carolan Haredon.”

“Really now! Are you sure it ain’t Lady Carolan Haredon?”

“Quite sure.”

“A pity. I’d have liked to have a ladyship in my kitchen.”

When Margery heard Esther’s story, she was a little more pleased with her.

“But you shouldn’t have been cruel to the young gent, my love! That’s why you got to Newgate … being cruel. Why, if you’d done what the young man wanted, you might have been ladying it in London Town instead of working in a Sydney basement.”

So much for life in the basement. It was not so easy to know what went on in the upper part of the house. Mr. Masterman was engaged in much business. He owned several stations, but that strip of country shut in on one side by the Blue Mountains and on the other by a great ocean had not proved such rich and fertile land as the first settlers had hoped it would. While the mountains remained an impenetrable barrier, the activities of pioneers on land must necessarily be restricted, and Mr. Masterman was not the sort to endure restrictions. At one time he had taken a schooner to the Bass Strait Islands and done very well out of the venture, returning with many sealskins and tons of oil; but these did not attract him as the land did. He kept an interest in the sealing business, but did not himself go again to sea. He arranged for the putting up of houses and other buildings; he dabbled in the politics of the town, and was a friend and supporter of the influential John MacArthur. though he managed to keep clear of the man’s quarrels with Governor King. He was clever and alert, a pioneer who had come to this country, not in the grip of the law, but in that of his own relentless and dynamic ambition. A new country had been discovered; he wanted to write his name boldly at the head of its history, side by side with that of Phillip, that man of genius and such patience who was the real founder of the colony and had brought out the first fleet; he wanted to write it beside that of MacArthur, him whom they called Kingmaker. There was little cruelty in his house; the lash was hardly ever used. But to him, Carolan was sure, the convicts were not people; they were merely a cheap and convenient form of getting labour. He had convicts on his sheep farms, convicts building roads and houses. Cheap convict labour was one of those stepping stones which were helping Gunnar Masterman to glory. But much of this was conjecture on Carolan’s part, built up from scraps of conversation chiefly with Margery, the talkative, who saw all men through amorous eyes.

“Poor man,” said Margery, ‘with that sickly wife of his! And not a son, nor yet a daughter to call his own. And him not the man to go around whoring. And her. with her room all to herself … Poor Mr. Masterman!”

“I do not believe he minds that she has a room to herself,” said Carolan.

“He does not mind that he has no son or daughter. He is cold as ice. You feel it.”

“So your ladyship feels it, does she! So your ladyship has been looking at Mr. Masterman, eh? Now Tom and Harry, riding in from the stations with the smell of cattle in their clothes, now they wouldn’t be the ones to attract your lovely ladyship! Of course not! Why, your ladyship’s eyes are all for Mr. Masterman!”

“How dare you!” cried Carolan. I… hate the man!”

“Hate your master, eh? Don’t forget the whip over the mantel.

“Margery,” he says to me.

“I trust you to use it judicial.”

“You can trust me, Mr. Masterman,” I says. And so he can. And listen, my lady, if I hear another word against your master, I uses it. It’s mutiny, nothing less!”

Margery would never use the whip, though she talked so often of doing so. Carolan laughed at her.

“Suppose I tell you about my lover how would that be?”

There now. me love, I knew you’d got one. You tell Margery. I understand. You don’t want this other scum to hear.”

It was so easy to please Margery; she loved the story of the squire.

“His rage, me love, when he found the bird flown! You was a sly one!” Carolan told of Everard.

“Parsons, me lovely, they’re men too. I can tell that. I said to him: “Now there ain’t no sense in staying out there shivering. There’s room in here for the both.” And what if he does mutter a prayer afore he gets in! Why, bless us all, it makes a change, now don’t it?”

But Carolan never said a word about Marcus; yet she thought of him often.

Esther was almost happy. Each night she knelt by her bed to say her prayers. Margery chuckled at the proceedings; Jin looked on with cold distaste, and Poll watched with vacant eyes; but none molested her.

“If only,” said Esther, ‘we could hear news of Marcus, how happy we could be!”

“You might be,” said Carolan.

“I could never be happy again.. You forget I have lost Everard, and my mother is dead.”

Esther was full of contrition.

“I am selfish! I think only of myself. Poor, poor Carolan!”

Carolan spent a lot of time talking to Margery, who loved to hear her talk. She told of the passion of the squire, who was not really her father; she told of Charles who had been cruel and had tried to kiss her; she told the story of how she had been locked in the tomb. “Ah!” sighed Margery, rocking with glee.

“You and me, me love, is as like as peas in a pod. You’ll be the spit of me when you grows up to be my age. And one word in your ear, lovely keep clear of pedlars!”

Carolan thought, Shall I be like her?

Her hands were rough with housework. She was an indifferent worker, and but for the fact that she was a favourite with Margery, the woman might have been tempted to get down the whip from above the mantel. Crockery seemed to slip out of Carolan’s hands.” Tis a mighty good thing that poor lady’s so sickly. Now if it was some ladies who took a pride in their homes, it would be the triangle for you, lovey, and the lash about your white skin.” Margery liked to pull the yellow dress off Carolan’s shoulder and stroke her.

“Lovely white skin it is, lovey. Dead spit of what mine was when I was twenty, and it ain’t so long ago neither.”

Carolan, restive in the basement, hating the dirty water into which it was necessary to plunge her hands, washing dishes, peeling potatoes, hating the smell of cooking, was bored. She longed for the fields and lanes round Haredon, and the feel of a horse beneath her. She asked a good many questions about what went on above stairs.

“There used to be a good deal of entertaining,” Margery told her, ‘but the mistress don’t often feel up to it nowadays. Her health’s bad, and getting worse. I can’t think that it’s what you might call a happy marriage. There she is, spending half of her time on the bed in her room with one of her headaches. Now if I had a nice upstanding man like Mr. Masterman for me husband …”

“Do you think she is really ill?” asked Carolan.

“Illness is a funny thing. There’s people who thinks they has it, and if they thinks hard enough they’ve got it. That’s illness just as the smallpox or anything else is. Well, that’s the sort of illness she’s got. Why, I remember a year or so back there was an epidemic of fever and people was afraid of its spreading; bless me. if she didn’t take to her bed and was burning hot, and the doctor coming. It wasn’t fever she’d got, but it was something well nigh as bad, and if it hadn’t been for Doctor Martin …” Margery smiled affectionately as she said the doctor’s name’… if it hadn’t been for him, she’d have had fever all right. That’s her for you.”

They sat round the table, Esther, Jin, Polly. Margery, James and Carolan. eating supper of bread and cheese, which they washed down with ale. It was lax in Margery’s kitchen. It might have been a servants’ hall back in England. Where else in Sydney were convict servants treated like this! Margery was responsible of course. She sat at the head of the table with James on her right hand and Carolan on hex left. She was well pleased, for the presence of James meant that she was still attractive enough to bring him round to the basement every night, though he had his own quarters with the other men in some outbuildings near the house. And there was Carolan, with her smouldering eyes and her lovely budding body to remind Margery of what she was a mere twenty years ago.

There was a dinner-party going on above stairs, and Jin wore a white apron over her yellow dress; she looked attractive in the lamplight.

Carolan said: Tell us what the table looked like, Jin.”

“It looked all right,” said Jin.

Margery said: “The table looked beautiful. I done it meself. The linen! And the glasses! I took in the pudding meself, pretending it was to see all was well, but really to have a look at them. Now he was at the head of the table, and a handsome man he is, and mighty pleased with himself he was looking too, and do you wonder! Quite some of the best people in Sydney was at his dinner table. And her… well, there she was at the other end of the table… in blue. Her fair hair’s getting thin, I noticed, and she was too pale. Too much lying a-bed, my lady, I says to meself.”

“Lazy old woman!” said Jin.

“Why should we slave like we do ..:

Margery’s eyes flashed.

“Now that’s enough of that. I’ll tell you why. Because you’re nothing more nor less than a murderess, and she… she’s a lady of the land. Another word from you and I ask James to get down the whip for me … aye, and to lay it about you for me. It’s mutiny, that’s what it is!”

Jin lifted a lazy eyelid and surveyed James. It was the first time she had glanced in his direction. There was something fiery and passionate about the gipsy, stormy and fascinating. James stared at her; Margery flushed a dirty pink; her jowls quivered. She looked very old, thought Carolan.

Esther said: “I saw her; she was coming down the stairs and the kitchen door was open. I saw her pass along the upper floor. Her dress was shimmering blue. She looked…”

“I know.” said Margery curtly, ‘like one of them angels you’re always praying to!”

Esther blushed and cast down her head.

“Here, Poll, you go and get me that bottle out of me cupboard,” said Margery.

“Go on. Don’t gape. Look sharp.”

“Tell us about her dress,” said Carolan to Esther.

“It was blue, and there was some silver about it, and she had silver slippers. She looked like a fairy … she is so small.”

“A sickly fairy!” said Margery, still angry.

“And next to him at the table was that Miss Charters. A big, bold girl, she is, and looking for a husband, if you’ll be asking me. There she was, right next to him, and you could see how he would have been the one she would have chosen if it wasn’t for the fact that he had a wife already.”

“Perhaps they’ll get rid of her,” said Poll, dribbling in sudden excitement.

“Perhaps …”

She came to the table and laid the bottle of gin beside Margery’s plate.

Margery caught her by her ear.

“Look here, girl! Don’t you run away with the idea that because you commit murders, other people do. Decent folk don’t, I tell you. There’s something bad about people as takes life, and I always have said it.”

Poll’s lips began to quiver. Her mind was unhinged by the murder of her baby. Carolan had seen her in her bed, holding a roll of dirty towelling against her breast, crooning over it. She had seen her in the light of morning, holding the towelling against her, asleep, with a smile of content about her face; she was dreaming of course that it was her baby she held; she could not go to sleep at night until she had assured herself that her baby was not dead and that she held it in her arms. Poor Poll, she talked incessantly of murder; during the day she tried to pretend that it was a natural thing … people did it as easily as they laughed or sang. It was the only way she could console herself.

Carolan had deftly worked a piece of flannel into the shape of a doll. She had sewn buttons on it for eyes, and had drawn on it a nose and mouth with a piece of charcoal. It had been touching to see the way the girl seized it. She took it to bed every night. How cruel of Margery to speak in that way to the girl. But Margery was put out because Jin was still regarding James from under those heavy lids of hers.

Carolan longed for the comparative peace of the bedroom, with Jin lying on her back, her hair a black cloud on her pillow, and Poll cuddling her doll and thinking it was her baby; and Esther, having said her prayers of thanksgiving, lying sleeping in her bed, while Margery and James groaned and giggled, and sighed and chuckled together in Margery’s creaking bed.

Now here in the kitchen the atmosphere had become sultry with the rumble of coming storm. Margery’s big brown eyes, usually soft with reminiscence, were hard in her red face; she kept looking at the whip over the chimney-piece and she lifted her head proudly, flaunting her freedom.

“Here!” she said.

“Let’s have a drop of gin. There’s no kick in this grog. Now gin’s the stuff. Why, back home you can get rolling blind for twopence. Bring up your glasses.”

“Not for me,” said Esther.

“Oh, not for you, eh? Too good, are you! But not too good to thieve from the lady you works for. I’ll have to keep my eye on you, me lady. You takes from one, you takes from the other.”