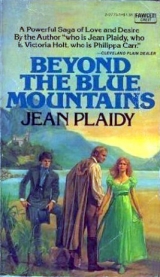

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“I did not faint,” said Carolan proudly, ‘but when I tried to speak my voice would not come.”

“Well,” he said, ‘you are all right now.” She leaped high into the air to show him that she was indeed all right. She was happier than she had been all the afternoon or for many days; she was not sure why, but she was a mercurial little creature, often very sad, often very happy; but rarely had she been as happy as she was now. Perhaps it was because Everard, twelve years old and admired and respected by the others, was being so kind to her.

While they were at the pump, Charles and Margaret came up. There was a cut right across Charles’s forehead and it was bleeding. Charles and Everard glowered at each other, and Margaret looked frightened.

Everard said contemptuously: “You can say you fell over one of the tombstones and cut your forehead. Carolan can say she was with you and she fell first, and you went down after her. That will do.”

He went on bathing Carolan’s eyes, and there was a deep silence. After a while they went into the house.

Mrs. Orland was distressed that the children had come to harm at her house. She bathed Charles’s forehead and looked in dismay at the strange appearance of Carolan. She sat down and wrote a note to Kitty, which when she had summoned Jennifer from Mrs. Privett’s room she gave to her to take to her mistress.

Everard said: “It is nothing much, Mamma!” and Mrs. Orland said: “For shame, Everard! Your guests …!” Then Mr. Orland left his sermon for a little while and came out to say a few words before they left, but he noticed nothing unusual. Mr. Orland would not notice, Margaret had once said, if you walked on all fours. It was altogether a most exciting afternoon for Carolan, until they were riding home in the carriage; then her elation vanished.

Jennifer said: “Now, what was all the fuss about?”

They told her the story they had told Mrs. Orland.

“It was her fault!” said Charles, pointing to Carolan. and Margaret did not defend her. She was disliking Carolan almost as heartily as the others did. The silly baby! Why, Margaret had been looking at Everard’s books and then suddenly he had escaped from her, which had wounded her deeply, for she always tried to pretend that Everard wanted to be with her as much as she did with him; and then when she found him he had been bathing Carolan’s eyes because the silly baby had been crying! He had escaped from her to go to Carolan’s aid. She felt impatient with Carolan, so said nothing when Charles laid on the child’s shoulders the blame for the afternoon’s disturbance.

“I’ll warrant it was I’ said Jennifer, and decided to ask for no more details.

“She shall be punished; she shall be taught that it she is very ill-bred to make trouble in other people’s houses. Ill-bred, indeed! Well, and what else can we expect?”

Carolan’s happiness gave way to despair. She wondered whether Jennifer would whip her when they were back in the nursery. Perhaps she would content herself with a threat that she should be moved from the room she shared with Margaret to a dark one of her own. Suppose that her threat was followed by that action which Carolan dreaded more than anything else in the world. Carolan prayed fervently that it would only be a whipping, but from the way in which Jennifer was smiling, she was filled with fear. She could not bear it if she were sent to bed alone in a dark room. It would be almost as bad as being shut in the dark this afternoon, and it would not end suddenly with the kindness of Everard, but would go on night after night.

She was frantic, thinking of it, and by the time they arrived home she had decided she must go to her mother and beg her to see that her bed was not moved away from Margaret’s room. It was not often that one could talk to grownups of one’s troubles; everyone realized that. Even people like Everard, who was almost grownup, knew that incidents like that of this afternoon must never be communicated to the grownups. But this time she could not help it; she would have to ask her mother to save her from the dark.

As soon as she was in the house she ran to her mother’s room. She knocked. Therese opened the door, and when she saw who it was, lifted her shoulders.

“Ah! The little one. There is no time this hour for the little one.”

But Carolan ran past Therese, for she had seen her mother sitting by the mirror. She wore a satin petticoat, and her hair was hanging about her shoulders. Carolan took a deep breath at the sight of so much beauty, and was very proud of having such a lovely mother. Now she would turn and say, “Hello, darling, tell me all about this afternoon.” Then she would notice that Carolan’s eyes were red-rimmed, and she would put her arms round her and kiss her and say: “What happened to my little Carolan?” Then, without saying anything about the afternoon’s adventure which was too horrible to be discussed with anyone, Carolan would ask that her bed should never, never be moved from Margaret’s room. That was how she planned it.

But it did not happen like that. Kitty saw her own lovely face vividly reflected in the mirror; Carolan was vague as a shadow standing beside her.

“Hello, darling,” she said. Then: “Therese, I will have the mauve ribbons in my hair, I think.”

She held the ribbons up to her hair.

“Do you like them, Carolan?”

Carolan nodded.

“They match my dress, darling, you see; there it is on the bed. You may go and look at it. You can feel how soft and silky it is … Are your hands clean, darling? Show. Yes, you go and feel it.”

Carolan felt the stuff of the dress. It was very soft and lovely, and would match the mauve ribbons beautifully. Carolan forgot to be frightened. Dark rooms and Jennifer’s anger seemed nonexistent when you were in this room, so full of bustle, the bustle of Therese and her mother; and Carolan, quick to catch a mood and share it, listened to the discussion as to whether it should be mauve or pale pink ribbons for Kitty’s hair, and it seemed as breathlessly important to her as the request she had come to make.

“And now,” said Therese, ‘the little one must fly away. There is much to be done, and so little time to do it in!”

“Did you hear that, Carolan? Therese is mistress here!”

Therese smiled; so did Kitty; so Carolan smiled too, and it was only when she was outside the door that she remembered she had not asked that which she had come to ask. She went back to the nursery and hid herself in a quiet corner, but nobody spoke to her, so she went over the adventure with Everard again and again, beginning at that part where Everard put the key in the door and let in the sunshine. Everard was her special friend, she kept reminding herself; he had talked to her as though she were older than five; and he liked her, she believed, better than he liked Margaret and Charles-which was a triumph.

She went to bed, and her bed was still in the room which she shared with Margaret; and when the candle was out and Margaret was sleeping and it really was rather frightening even though she could hear Margaret’s breathing in the next bed, it was not with her mother that she, after her usual fashion, held a whispered conversation, but with Everard.

The year that Carolan was nine was one of the most eventful of the century. France declared war on England, and Charlotte Corday assassinated Marat in his bath; Louis XVI was executed that January and his queen followed him in October; that year saw the beginning of the Reign of Terror in France and the wave of uneasiness which swept over England because of it. But Carolan was unconcerned with events outside her nursery. She awoke on the morning of her birthday in great excitement. She now had her own room, but she had lost much of her childish fear of the dark. Sometimes, of course, when she had heard an eerie story she had nightmares, but that was not often; then she would dream she was locked up with the dead, and that dream persisted. But it was a dream with a happy ending, and when she awoke, perhaps screaming, trying to fight off queer dark shapes, she would think of Everard’s coming through the door, picking her up and talking to her so kindly. Then she would have a long imaginary conversation with Everard, and picture his face so clearly and hear his voice so distinctly that all fear would leave her. They were friends, she and Everard, and it was extremely exciting to have a friend who was so much older than oneself. It did not matter about being ugly. Her hair had kept its reddish tinge; her eyes had stayed green. Jennifer was for ever saying: “Green eyes for greedy guts! I do declare you grow uglier every day.” Charles took up the refrain: “Greedy guts! Greedy guts!” It was not a very pleasant name. But when she said to Everard: “Everard, how ugly am I? As ugly as old witch Hethers?” Everard had laughed.

“Silly! You are not ugly at all; you are all right as good as most.”

“As good as Margaret?”

“Oh, better than Margaret!” and Margaret, fair-haired, blue-eyed Margaret was the prettiest person Carolan had ever known except Mamma, of course, who was lovely as a picture. But then Everard hated Margaret because she would try to talk to him and be with him; so that was why he thought her ugly, just as Jennifer thought Carolan was ugly, because she did not like her.

What exciting days birthdays were. She imagined what they would all give her; a dress of lace and ribbons from Mamma, because one always thought of lace and ribbons when one thought of Mamma. From Everard a riding whip to be used when she rode Margaret’s pony. From Margaret a saddle of heavenly-smelling leather. She could not lie abed when so many beautiful gifts were awaiting her. She sprang out and danced to the window. What a lovely morning, with an April sun that was so beautiful because it had remained hidden so long, and an April freshness in the air, and the blossom just beginning on the fruit trees, and the daffodils under the oaks, and the birds wild with excitement because it was Carolan’s birthday!

She stood, her head on one side, listening.

“Carolan.” sang the birds.

“Car-o-lan!”

“Here I ami’ she cried.

“Did you know it was my birthday?”

She pressed her nose against the glass, laughing. Then she danced to the cold water jug, poured out some water into the basin, and washed.

When she was dressed, she opened the door and looked out into the corridor. There was no sound from either Margaret’s or Jennifer’s room. She stood uncertainly in the corridor. If Jennifer heard her about so early, there would be trouble. She grimaced at Jennifer’s door and tiptoed past it. Down the flights of stairs she went, to Mamma’s room. How rich it seemed down here, compared with the shabby nursery quarters. Here was her mother’s door, with Therese’s next to it. She turned the handle and stood on the threshold, looking in. Mamma was sleeping, her fair hair in disorder on the pillow. Carolan tiptoed into the room and stood by the bed, watching. Mamma’s lashes were long and gold coloured, and her full lips were parted. Carolan stood for some minutes, watching; then she whispered: “Mamma, I am here.”

Kitty opened her eyes. She had not altered very much in four years; she preserved her beauty with the greatest care, and Therese, with her skin lotions and tonics, was a wonder. True, she had put on flesh, but as Therese assured her, it was in the places where it was well to put it.

“Carolan,” said Kitty drowsily.

Carolan leaped onto the bed and knelt there.

“Mamma, do you know what today is?”

“Tell me, darling.”

“Oh, Mamma, do you not know?”

“I am so sleepy yet, Carolan. Kick off your shoes, darling, and come in.”

So Carolan kicked off her shoes and came in; she snuggled close to her mother.

“Shall I tell you then?”

Yes, tell me.”

“It is my birthday. I am nine years old today.”

Kitty held the small body closer. Nine years ago that she had suffered so deeply. Nine years of humiliations from George Haredon. She put her lips against Carolan’s cheek, and Carolan lay still, contented. Kitty lay still too, thinking of the wonder of her first love. Had I married Darrell, thought Kitty lazily, I would have been a true and faithful wife to him. I have always been searching for someone like Darrell that is it. Now she was wishing she had been a better mother to the little girl lying beside her. She would see more of the child from now on; she would look more closely into the nursery life of Carolan. Was Jennifer Jay cruel to her? She had never asked Carolan that question, for if Carolan said Yes, what could she, Kitty, do about it? George paid his children’s governess; he would be the one to decide whether she should go or stay. How she hated George Haredon.

Ah! If only Darrell had not gone to Exeter! If they had gone to London together and married, there would still be this dear little Carolan and how they would have loved her, both of them!

Am I to blame ? Kitty asked herself.

Carolan’s little body was quivering with excitement. Her birthday, of course, Kitty thought in panic, and I forgot. She will be expecting me to have remembered. Peg always used to remind her of Carolan’s birthday, but Peg had married one of the farm labourers two years ago, and left Haredon. Then Dolly had taken it upon herself to remind her, but six months back Dolly had run away with a gipsy whose band had made their camp nearby. And how could she tell this little daughter that she, her mother, had relied upon two of the lower servants to remind her of this great and important day.

Kitty resorted to subterfuge, for subterfuge came easily to her.

“Carolan, I am very unhappy about your present. It is not ready, darling. They have disappointed me.”

“Mamma, when will it be ready? Tomorrow?”

“I hope so, darling.”

Carolan squealed: “Then it will be like another birthday tomorrow, Mamma!”

What a sweet child she was! Kitty’s eyes filled with tears. She stroked the unruly hair with the red in it; she kissed the smooth childish brow.

“I was so afraid you would be disappointed, darling; that it would be spoiled for you.”

Carolan’s hands round her neck were suffocating.

“No, Mamma, not spoiled … not spoiled at all. Tell me, is it blue … or pink?”

“Ah!” said Kitty.

“That would be telling.”

“It is pink. I know it is pink!” Carolan’s eyes were dark with hope.

“It might be green though! Mamma, is it green?”

So she wanted green, did she?

“Well,” said Kitty, suffused with mother-love, ‘as a matter of fact… it is… well, I ought not to tell you, ought I?”

Carolan was laughing hilariously now; she put her ear close to her mother’s mouth. Beautiful a child’s ear was, soft and pink like a sea shell.

“Whisper, Mamma!”

“It is green,” whispered Kitty.

“Is it silk or satin?”

So she wanted a dress. She was growing up, to want a dress. A dress she should have. Kitty must … simply must remind Therese to go out and buy one this morning. A white dress it should be, with green ribbons.

“I shall tell no more!” said Kitty, and Carolan knelt on the bed and rocked backwards and forwards in ecstasy.

Perhaps, thought Kitty, she would not send Therese; perhaps she would go herself to buy the dress.

“My little daughter!” she said.

“My dearest little daughter.”

And Carolan, overflowing with love for her, flung her arms once more round her neck.

Soon, thought Kitty, there will be another birthday, and another and another. Soon she will be fifteen, sixteen, seventeen. I was seventeen when I met Darrell.

Kitty held her child to her sharply. What had Carolan heard about her birth? Anything? Was it possible that there had been no hint, no whisper of what had happened? It was hardly likely. Wicked Jennifer Jay might have said something. Aunt Harriet’s thin-lipped disapproval? George’s ribaldry? Had any of these been noticed by the child?

Kitty raised herself and looked down into the face of her daughter. A sensitive face, very like Kitty’s own; very attractive it was going to be one day it was now with a slightly different attractiveness from Kitty’s, less obvious perhaps; but then it was not easy to tell. There was a look of Darrell in the child’s eyes, Kitty thought. She must hear it first from me! And impulsive as Kitty always would be, she decided there and then to tell her something.

“Carolan, lie still beside me. I want to talk to you. Has anyone ever said anything to you about about me … and … the way you were born?”

Carolan said quickly: “Yes, Charles says I am a bastard and not the squire’s bastard at that. He said it is well enough for a squire to have as many bastards as he likes, but I am not even a squire’s bastard.”

Kitty cried out to stop her.

“Oh, the wicked boy! I hate him! He is like his father.”

“I hate him too,” said Carolan happily.

“But I want to tell you, darling, about how you were born. It will not be easy for you to understand, but will you try?”

Carolan nodded. How lovely it was in her mother’s bed! There were sweet smells of powder and ointments in the room and the ornate posts of the bed enchanted her. She would have liked to draw the curtains tightly and be shut in with her mother.

“Darling, please listen very, very carefully. Years ago I loved your father.”

“Not the squire!” said Carolan.

“He is not my father, is he, Mamma?”

“No, not the squire. You see, I loved your father very dearly, and we were going to London to be married, and we were going on the coach. He went to Exeter to see about our going, but he went into a tavern there, and while he was in that tavern, the press gang took him.”

Kitty was crying at the memory, for she cried as easily at twenty-seven as she had at seventeen.

“Mamma, who is the press gang?”

Kitty clenched her hands and answered vehemently: “A wicked gang of cruel men who take men wherever they may be and force them into the Navy.”

“But why, Mamma?”

“Because they need men for the Navy.”

“And would they take any man at any time? Perhaps they will take Charles.”

Kitty whimpered: “How different my life would have been but for the press gang! We should have been together, your father and I. How you would have loved your father, darling!”

Carolan’s eyes were wide and dark; she could not grasp this very clearly. Her father not the squire in a tavern and a mysterious group of men called the press gang; they had cruel faces and they dragged him away while he screamed to be released.

“Oh, Carolan,” cried Kitty, ‘do not blame me, darling. Do not listen to evil tales of me. Remember only that I loved your father; I loved him too well.”

“Mamma, is there still the press gang?”

“There is still the press gang!” She added wildly: “There always has been; there always will be! Oh, my darling, the wickedness … the wickedness. And when you were born, my precious child, you would have had no father, so I married the squire in order to give you one.”

“But how could you give me one if I had none, Mamma?”

“Carolan, my own daughter, try not to blame me!” Carolan, whose nursery days were full of taking blame for real and imaginary sins, did not understand for what she should blame her mother. But it was pleasant in bed, and she was indeed sorry when Therese came bustling in to lift her hands and murmur: “What is here! What is here!” in her funny accents.

“It is a birthday little girl!” said Kitty, all tears gone, full of smiles.

“A wicked one,” said Therese, ‘to spoil her mamma’s beauty sleep!”

“Ah, but it was sweet of her to come, Carolan, my darling, come again, and we will talk often of … you know what. It is our secret, and we will talk together of it.”

Carolan nodded. What a wonderful birthday morning! She had come, hoping for a present, and had discovered a secret. But then, were not secrets as amusing and exciting as presents?

“I will come,” she said.

“And now.” said Therese, lifting her from the bed, ‘you will go, yes?”

She ran to the door, looking back once to smile at her mother, and the look that passed between them was an acknowledgement of a secret shared.

She ran along to the nursery, where Margaret and Charles were already having their bread and milk. Charles stared down into his plate, eating hurriedly. He always ate hurriedly in the nursery. He was fifteen, and going away to school shortly; he thought eating in the nursery was beneath his dignity. Margaret was looking excitedly at the parcel she had put by Carolan’s place. Jennifer sat at the head of the table.

“Ah!” said Jennifer.

“And where have you been, Miss? I have been to your room once for you!”

That,” said Carolan, ‘is no business of yours, Jennifer!”

“Come here!” said Jennifer.

Carolan tossed her head and went to her place at the table.

“I’ll tan the hide off you after breakfast!” said Jennifer. She always felt ill in the morning too tired to put any energy into whipping the child.

“Perhaps!” said Carolan.

“No perhaps about it. Miss!”

Charles looked up, interested, as though he hoped Jennifer would begin now.

Carolan said boldly: “You could not tan the hide off anybody, Jennifer Jay. You are not much good at tanning; you are getting old!”

Jennifer stood up. Charles put out his foot, so that if Carolan tried to run she would have difficulty in getting past it. Carolan, feeling concerned, shouted in bravado: “You are getting old, Jennifer Jay! In the kitchen they say you are getting too old. Jennifer Jay!”

It was worth any whipping, to see the colour run out of Jennifer’s face.

“Yes!” said Jennifer.

“It is to be expected; you would talk to those sluts in the kitchen, you! That is your place down there with them. I can tell you what will happen to you, Miss Carolan.”

“What?” said Carolan. who really wanted to know.

“You will end up on a gibbet, or in Botany Bay!”

Margaret was looking at Carolan in shocked wonder. Charles was laughing his agreement. Carolan quailed; there were those who said that Jennifer Jay was almost a witch.

“No!” cried Carolan, feeling rather frightened.

“It is you who will end up on a gibbet, Jennifer Jay!”

Charles put his face close to Carolan’s.

“Do not forget it is a birthday, young Carolan!”

“I do not forget. I am nine today! Yesterday I was eight. Today I am nine!”

“Nine is not much to be!” said Margaret.

“But here is a present for you, Carolan. From me to you. A happy birthday! See. I have written it on the paper there.

“A happy birthday from Margaret to Carolan”.”

“Oh, thank you, thank you!” Carolan hunched her shoulders with delight.

Margaret said impatiently: “Open it! Open it!” And, fingers trembling with excitement, Carolan opened it. Inside the packet was a book-mark in silk, with flowers embroidered on it, and “Carolan Haredon, April 19, 1793’ worked in red and blue. One of Carolan’s great gifts was to be able to disperse elaborate expectation and find complete joy in the reality. She forgot the saddle she had dreamed that Margaret would give her; now she was completely absorbed in the beauty of the book-mark.

“Margaret, it is lovely!”

“You do like it?” cried Margaret eagerly.

“I did those flowers my self I’ “They are beautiful.”

“There are a few bad stitches in the red ones,” said Margaret modestly.

“I cannot see them!” Carolan warmly assured her, and they smiled shyly at each other.

Charles said: “Here! Margaret’s not the only one who’s got a present for you, baby.” Carolan stared incredulously at Charles, for from his pocket he took a brown paper packet.

“Oh … Charles! Thank you.”

“Happy birthday!” said Charles.

“Thank you! Thank you!” Carolan smiled at him very sweetly. She felt ashamed that she hated him when she came into the room. She took the package; it was soft. There was no sound in the nursery but the crackling of paper. Beneath the first wrapping was a second one.

“Go on!” said Charles.

“You are slow.”

“I wonder what it is,” said Margaret.

“Charles, you did not tell me… though I told you the book-mark was for Carolan!”

“Oh,” cried Charles, ‘she will love this better than your silly book-mark. She will take it to bed; she will keep it under her pillow; she will carry it wherever she goes. She will love it so much.”

“Margaret,” said Carolan, ‘the book-mark is lovely.” And she thought: What would I take to bed with me? What would I keep under my pillow? What would I carry wherever I went?

What a successful birthday, with even Charles remembering it!

The parcel was open. Carolan squealed, and dropped it; her face was ashen. Lying in the paper was a tiny shrew mouse which had been dead some days.

Jennifer began to laugh shrilly.

“She will take it to bed with her! She will keep it under her pillow! She will carry it wherever she goes!”

Carolan raised her eyes and looked at Charles looked at him with such utter loathing that momentarily his laughter was quelled.

Margaret said: “That was beastly … to pretend it was a present!”

“Be silent!” said Charles.

“Bah!” said Jennifer.

“You cannot see a joke. Look at the little Greedy Guts! Ready to burst into tears, I do declare.”

Carolan hated death; she ran from death. If she saw a funeral in the village, with all its black trappings and the mourners all covered in black, she could not sleep that night, and when she did, her sleep was disturbed by frightful dreams. Birds, animals, people … when they were dead they changed subtly; they were not birds, animals, people any more. She could never be happy, thinking of death. And here, on her birthday, was death presented to her in the shape of the small limp body of a shrew mouse.

But the fun had only just begun for Charles.

“So you would throw my present on the floor, would you? You ungrateful little beast! Pick it up… Pick it up, I say! Do you not love its soft silky body? Stroke it, baby. Its name is Carrie -named after its new mistress, you see. Pick it up, I say. Kiss it!”

“I will not touch it,” said Carolan.

He caught Carolan in his strong arms; she began to kick.

“Nine years old, she is!” he said, looking at her derisively.

“One would think it was nine months!” He narrowed his eyes.

“Carolan, are you going to pick up my nice present? Are you going to carry it in your pocket, take it to bed with you, my child?”

“No,” cried Carolan.

“No!”

Margaret looked unhappy. She hated to see Carolan tormented; but what could she do about it? She was not yet thirteen herself, so what could she do against Charles and Jennifer?

Charles gravely put Carolan down; his brown eyes that were flecked with yellow were the cruellest eyes in the world, thought Carolan, and when they blazed in anger they were not so cruel as they were when they laughed in this quiet way.

He picked up the mouse by its tail; then he caught Carolan.

Carolan shut her eyes tightly that she might not look into Ms face.

“Open your eyes,” said Charles.

“I will not.”

“You will,” said Charles.

“Do you think I bring you presents that you may haughtily shut your eyes and not look at them?”

“I hate you!” sobbed Carolan.

“Stop this,” interrupted Margaret.

“It is so silly.” Jennifer said nothing; she just sat there, leaning her arms on the table.

“Carolan,” said Charles, ‘must learn not to be a silly baby.” With a mighty effort Carolan, taking Charles off his guard, wrenched herself free. She ran towards the door.

“Mamma!” she screamed.

“Mammal’ But Charles dashed at her; she fell, Charles sprawled on top of her. Carolan beat at him with her fists; Charles was helpless with laughter, and Carolan’s sobs and Charles’s laughter mingled oddly together. George Haredon, opening the door, stared at the scene in amazement.

“What is this?” he demanded, and there was sudden quiet in the nursery.

Charles and Carolan got to their feet. The squire did not look at Jennifer; he was heartily sick of looking at Jennifer. He looked from Charles to Carolan.

“What is this display?” he said, and he put a heavy hand on Carolan’s shoulder and turned her face up to his.

“Tears?”

“She is such a baby, master,” said Jennifer. Carolan stamped her foot.

“I am not a baby!” she faced the squire furiously.

“I do not cry because I am a baby. I cry because I hate him.”

“Nice words! Nice words!” said the squire, and sat down heavily on one of the chairs at the breakfast table. It creaked under his weight. Jennifer cursed her ill-luck. There was grease on her gown which she had not bothered to remove; her halt was limp and in need of a combing. How was she to have known that the squire would visit the nursery so early! Could it be because of the brat’s birthday? Had he come to the nursery early for Charles’s birthday… for Margaret’s?

“Now,” said the squire.

“I will hear why there is all this kicking and screaming at this hour of the morning.”

“Miss Carolan is a silly little baby.” began Jennifer.

“She wants a good whipping…”

George Haredon said, without looking at her: “I am not addressing you.”

Ugly colour flooded Jennifer’s face. He could talk to her like that, after… everything?

“Charles,” said the squire, ‘tell me why you think it so amusing to make a little girl cry.”

Charles said: “She is such a baby. It was a joke. That was all, and she could not take it.”

“I will hear the joke,” said George.

“Oh, it’s a silly joke really, sir,” said Charles.

“I have no doubt of that. But when I say I will hear it, I mean it. And listen, boy. I will be judge of whether it is silly or not. Carolan, come here. Margaret too.”

They stood before him, all three of them, Carolan in the middle. The squire looked from his own two children to Kitty’s child. Why. he thought angrily, do I have to have those two, and why shouldn’t she be mine! He had tried to dislike her, God knew; he had tried to ignore her. But she would not be disliked, nor ignored; she intruded into his mind at odd moments. Her skin was like the bowls of rich cream that were served at his table cream with the bloom of peaches in her cheeks; now there was angry red there, like roses. And the eyes that glittered with tears were decidedly green. The red in her hair delighted him. What was it that she had, and Kitty had, and Bess had had, and no one else in the world seemed to have? Why was she not his child, instead of these other two? Unnatural father that he was! But then, he felt himself to be unnatural in a good many ways. When a man got older he was more given to self-analysis than in his younger days. There were days when he did not feel like hunting not the fox, nor the otter, nor women could make him want to hunt; then he sat in the sun or by a fire and thought about himself … not what he wanted to do, nor what he wanted to eat, but what he was. Searching, searching for something that was George Haredon, and the tragedy of it was or perhaps it wasn’t a tragedy, merely an irritation that he did not know for what he searched. First he had sought it in Bess. Ah! If only he had married Bess! But Bess had run off with an actor. Then he had sought it in Kitty, but Kitty was a wanton. And now he sought it in the child. Little Carolan as near his daughter as made little difference really. Little Carolan, green-eyed, red-haired, with that elusive and mysterious quality which had been Bess’s, which still was Kitty’s.