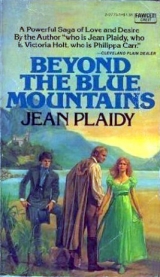

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 29 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“You are talking nonsense.” said Carolan.

“Am I? I do talk nonsense, do I not! I have been so tired; I am waking now. I feel as if I am struggling out of darkness, and that words are a sort of rope I cling to. Oh, you smile, Carolan; you are so strong and practical. You are very like him, Carolan, in a way … in a way. Once he wanted me to get well; he was very eager that I should. But that was not because he cared about me. Oh, no! He wanted me strong and well because he wanted us to have children. Sons he wanted. Big, strong men to go on living when we are dead; to build up this country into a great place, independent of England. I am sure that is how he feels. He is such a strange man. Carolan. You would not know, because you always see him as the master, so careful, so right in .everything he does.”

“Why do you not try to sleep again?”

“Sleep! I have slept and slept. Do you know. Carolan, sometimes I feel the desire to go on sleeping, not to wake up. It is as though, when I lie in the deep sleep, hands are laid upon me, soothing me, bidding me to stay there in the peaceful darkness for ever… not come back, you see…” Carolan’s eyes glittered.

“You took too much of the drug; you must be careful.”

“I must be careful, Carolan. I will. When you are tired, it is so beautiful to sink into that deep sleep.”

“I should not take it so often, if I were you.”

“Oh, Carolan, do not stop me. Please do not stop me!”

“Who am I to stop you?” said Carolan. The glazed eyes were lifted to her face.

“You are so good, so kind, so sympathetic. I do not know what I should do without you. You are strong; I have always been attracted by strong people. He is strong; that was why I was attracted by him, I suppose. I wish I could have been more the sort of wife he wanted. When I was not so ill, I must have pleased him. We entertained a good deal. It was only after our marriage that he was on such good terms at Government House. He owes me a little, Carolan.”

“What would he say, were he to know about the child?”

“You would not tell a soul!”

“Of course I would not; you told me in strictest confidence.” She laughed.

“But he would be very angry, I do declare.”

Lucille was awake now, wide awake; the thought of discovery could make her throw off the last effects of the drug.

“I should be terrified if he knew. He … is ruthless, Carolan. I often wonder what happened to him before he came to Sydney.”

“Did he not tell you?”

“Never!”

“Not even when… when you were lovers?”

“Lovers! What do you mean, Carolan?” Carolan wanted to laugh out loud. They had never been lovers; they had never been anything but a suitable match for each other. That accounted for his happiness now, for his complete simplicity, for the youthfulness of his lovemaking. Carolan felt she ought to have been amused, discussing her lover with her lover’s wife, but she was only ashamed. She had to force herself to go on.

“I mean during the engagement.”

“It was very short; there was no reason why it should not be. I was so sure it would be a successful marriage then.”

“Oh, come,” said Carolan falsely, ‘is it not now?”

“That I do not know.”

“You are thinking of the child.”

“Oh, Carolan, please do not speak of that again.”

“I will not, if you wish it so, but if he were to know … He would consider it a great wrong.”

“Oh, I could not face it, Carolan, you know I am not strong.”

“He would have thought it your duty to face it.”

“I was very wicked, Carolan. That is what you are thinking.” Lucille caught at her hand.

“But now. Carolan, it does not matter. I am sure he is resigned … I am sure of it! He used to come in and look at me, and he would frown and ask me how I was, and I would know that he was thinking of children.

But lately he has ceased to think of them. He has changed. He is a different man. He looks … as though he finds life good, no longer frustrated. He is a man who is always reaching for a goal. Now … perhaps I talk rubbish … but it seems to me as though he is no longer teaching, that he is satisfied with life.”

“You think he his given up hope of children?”

“Carolan, I do. I have been careless of late. The bottle … it was by the side of my bed … on the table here, when he came in.”

“What did he say?”

“He said nothing.”

“He could not have seen it.”

“He is usually observant of such things.”

“But had he seen it, he would surely have said something?”

“He merely looked at it. He said: “How are you today, Lucille?” very gently, almost tenderly. And I felt then that he loved me more than he had ever done.”

“But should he not have been perturbed at the sight of the bottle?”

“Why should he? Perhaps he did not know what it was; perhaps he thought it was some tonic. I was trembling all over. I was terrified that he would take out the cork, that he would discover what it was. that he would forbid me to take any more.”

“You would have obeyed him?”

“I must sleep, Carolan. Doctor Martin says the best thing I can do is to sleep.”

“But he would not give you this! You have to go to your shady convict doctor to get this, to the one who helped out about the baby…”

“I used to think you understood, Carolan.” she said and her voice shook with fear.

“I do understand, but you wronged him deeply. To marry a man is to promise him children. You did not keep your promise. Come. Lie down. Do not distress yourself; you are not strong enough. You should never have married.”

“But. Carolan. I do not think he minds now. He does not worry about my health as he did, and I know he was once waiting lot me to get strong so that we could have children.”

“He does not think of children now, you tell me.”

“Sometimes it seems he does, sometimes not. He told me of that girl. Esther. Is it not good of him, to concern himself with her? He is arranging everything for her, and when he talked of her I saw a gleam of something in his eyes.

“She is going to have a child,” he said.

“I am arranging for her marriage to the man responsible.“I thought he was wonderful then, so good.He wants to make this place a beautiful country; that is what I think. He wants to set it in order; he is like that … he wants to set everything in order. He was envious of that man because he is going to be a father. He still feels it.” She shivered.

“If I could have given him children …”

“Listen,” said Carolan.

“You must not fret. It is bad for you. You must forget that you cheated him, that you killed his child.”

“Killed, Carolan!”

“There! I have hurt you. No, no! That is not murder; it is only when a child is born that killing it is murder. I will put this bottle away. You must not take so many doses. They will cease to be effective if you do, and it would be dangerous to increase the dose. I will cover you up. There is a chilliness in the air. Now try and sleep gently, naturally, and I will go down to the kitchen and order your bath.”

Carolan saw that fear drew down the corners of the woman’s mouth. Murder! She had not seen it like that before. Her hands trembled. They often trembled. It was too much drugging that did that to her. Fool that she was! She deserved her fate surely. She had had everything, and she was afraid to live the easy life that had come her way.

Carolan went downstairs. There was a light in her eyes that might have been the light of battle.

“Poll!” she said.

“Heat water for the mistress’s bath.”

Poll! Who had murdered her baby! A different sort of murder, it was true. For the rich one law; for the poor, another. Poll would never have been able to pay the convict doctor’s price; so she had murdered her baby after it was born … with those skinny hands of hers. Lucille, the lady, had had it done for her.

What was the difference? Poor Poll. Poor Lucille! Not for her to waste her pity on them; she needed all her resources to fight for herself.

Esther was not there; she was with Marcus now. Picture Esther working at some garment in happy preparation; happiness made Esther beautiful, and Marcus was very susceptible to beauty. Margery, at the table, watched her slyly. She had a strange and grudging affection for the lecherous old woman.

Margery’s eyes went all over her. Fear shot through Carolan’s heart. Those sharp eyes would see whatever there was to be seen.

“Ha, ha! Not often we have the honour…”

“You put it very charmingly.”

“Don’t suppose you’d deign to drink a glass of grog with me now. Don’t suppose it for a moment!”

Carolan laughed, showing her sharp white teeth in a rush of friendliness. The woman was more than ready to meet her half way.

“That is an invitation I cannot refuse.”

“Jin. Bring out that bottle.”

Jin came sullenly, and Margery made her pout it out for them.

Margery smacked her lips.

“Good stuff, eh?”

“You know how to get the best out of life, Margery!”

Now what did that mean? Who knew what she would be saying to the master? Queer things women would say to men in bed o’ nights. Margery touched Carolan’s breast with a caressing finger.

“Now don’t you too, me love?”

Carolan laughed falsely. They were suspicious of each other. Sly smiles on Margery’s lips. Admiration, envy, excitement to have the girl sitting so close. You couldn’t help your thoughts, now could you? And for all his funny ways, he was a fine figure of a man. And to think of her ladyship, going with him out of pique for, not being born yesterday, Margery knew, sure as fate, that it was the other one she wanted. To use the master like that! The master! It was the best thing she had heard for years. And here was the girl, sitting right next to her, her lovely body close, the body the master was in love with! It made you feel funny, no mistake!

That slyness, thought Carolan, that knowledgeable slyness. How can she see? What is she thinking? She knows so much. It may be that she sees what I cannot. They were very friendly with each other, almost ingratiatingly so.

“Things ain’t what they was. with you out of me kitchen, dearie.”

“I shall often come down for a chat like this.”

“And how do you like sleeping in a nice feather bed?” .Hot colour ran up under the girl’s cheeks. Margery had a vision of her going in to the master. No, of the master’s going in to her; she would see to that! Margery could have rocked with laughter.

“It is very comfortable, of course.”

Margery nudged her.

‘ “Course it’s comfortable!”

Poll came in eventually with the water.

“Carry it up,” said Carolan.

There she was. giving orders in Margery’s kitchen! Carry it up yourself, me lady, is what she ought to be told. But how can you say such things to a girl what’s got the master where she wants him? And that in a house where the mistress goes foe nothing!

Poll went up with the cans; Carolan followed. Margery stood at the bottom of the stairs, watching.

“Knock at the door,” said Carolan, ‘and tell the mistress her bath is ready.”

“What!” said Poll.

“Knock at the door, I said.”

“What, me!”

Carolan went across the toilet-room. She knocked at the door, listened for Lucille’s sleepy “Come in,” then opened the door and pushed Poll in.

Lucille looked up. Poll stared at the woman in the bed; at the luxury around her.

If… yes?” said Lucille.

“Bath’s ready!” said Poll, and fled.

A few minutes later Carolan went in.

“Your bath is ready.”

“Yes. A… that girl told me.”

“Poor Poll! She’s a sad wretch, do you not think so?”

“Dreadful.”

“More than a little crazy.” Carolan smoothed the silk coverlet angrily.

“Newgate! Transportation! They can be terrible experiences; none knows how terrible unless experienced.”

“Carolan, my wrap please.”

“She was sentenced for murder. She murdered her baby. Foot Poll!” Carolan arranged the wrap round Lucille’s shoulders.

“Why, you are shivering! It has turned quite chilly. Come now … while the water is hot.”

Her room was just above Lucille’s – a small room with a feather bed. If Lucille needed her in the night, she could knock on the ceiling with a long stick. She never did.

He came some nights. Carolan would lie listening for his step. He would knock lightly, and she would be at the door, opening it swiftly and letting him in. Sometimes this stealth amused her; sometimes it disgusted her. She seemed to be full of inconsistencies these days. Sometimes she saw herself as a scheming woman, a woman who has suffered much and is determined to lie on a feather bed for the rest of her days. Wild thoughts came into her head when she was in that mood plans and schemes. But there were other times when she saw herself differently. She had gone to Masterman, she believed then because she had known Marcus must marry Esther, and only when she had taken her determined steps away from Marcus could she bear to give him up. Perhaps she did scheme; perhaps she had made a great sacrifice; she was not entirely sure. But whatever had been that primary motive, her feet were now firmly set upon the road she must take. That was why, if he stayed away for more than two nights, she grew frightened. Once he was with her, he was completely hers, and she could do with him as she wished. But when he left her she was afraid; she, who had made so many false steps, was afraid of making more. Love between them was to her intensely exciting, and his very shame in their relationship added a piquancy for her. But she was afraid always that one day he would say he was going away, perhaps to work on one of the stations for awhile, where he could avoid her attraction. It was exciting to know that he had meant to talk of ending their relationship, and to lure him into complete surrender, to make him admit that he would face anything rather than miss this happiness. There was power; in all but his desire for her, he was the strong man; that made his downfall more gratifying, that in itself made her enjoy these months, made her hold her head high, made her heart glad even when she heard of the birth of Esther’s son.

He would lie in her arms, this master of men. and talk a little. She was sure he had never talked to anyone else as he talked to her. He wanted her, not only as bedfellow, but as companion to hear about his ambitions, to listen to the stories of early struggles. She was determined to be everything to him, to strengthen the bonds about him.

He was a strange man cold and passionate: sometimes she felt she hardly knew him; at others he seemed as simple as a child; and ambition and idealism were the keystones of his character. He spoke shyly of his dreams. Himself and his family a big family, a family of boys to cultivate this land which he loved with a passion that, until he had met Carolan, he had bestowed on nothing else; girls to breed more men to cultivate the glorious land. That was what he had wanted. Himself a man of importance in the town, Governor perhaps; though it was hardly likely that the government at home would approve of that.

He grew excited, talking of his adopted country. He liked to think of the arrival of the first fleet.

“Eleven ships, Carolan! Only that … to start a new world! What a glorious moment it must have been when they sighted land!”

Carolan thought of the convicts, battened down under the hatches, and she was silent.

“And Phillip… that great man… I like to think of his sailing into Botany Bay that great wide-open bay and turning from it into our own Sydney Cove.

“The finest harbour in the world, in which a thousand sail of the line may ride in the most perfect security.” It is the finest harbour in the world. Why should not this be the finest country? In years to come people will remember that it was men such as I who made this new world. Pioneers who left the home country to start a new life. Men like Phillip, that great genius, men who with small worldly goods, but great courage, set out to open up this great new world of the South.”

He was lyrical about the place. When his enthusiasms were roused they were prodigious. His love for her, his desire for children, his love of his adopted country all were the enthusiasms of a strong man.

And below lay that useless woman, that selfish woman who had denied him his dearest wishes.

Carolan was waiting for him now. Tonight she must be seductive, cautious and wise, for much was at stake. Tonight she was fighting not for herself alone.

The mirror told her she was beautiful. There was a new softness in her eyes, and a new fierceness too. A tigress at bay, preparing her lair.

She was trembling with fear. What would he say… this puritan? What would he do now? Did she really know him very well? Could she be sure of his reactions? She was terrified that he would not come. All day she had rehearsed her speeches.

Her heart felt as if it had leaped into her throat when she heard his footsteps on the stairs. She opened the door, and she was in his arms.

They would make love, and then he would very tenderly tell her that he was a monster and that he must think of some plan which would help them both. But before he could talk in that way she said: “Gunnar. I am frightened, terribly frightened!”

“Why?” he said.

“What has happened?”

“Can you not guess?”

He was silent, but she knew by the hammer strokes of his heartbeats that he was deeply affected. So much depended on the way he felt about it whether his joy would overcome his conventions.

She released herself from his embrace and sat up; she drew her knees up to her chin and put her arms round them; her bait fell about her face. She was aware of her own beauty; she could see herself in the mirror; she could see him too.

“It is a strangeness that has come over me. Gunnar. I cannot help but be happy… frightened as I am!”

He got up; he put his arm round ‘her.

“Carolan …” he said brokenly.

“Carolan … I .. have done this… I…”

“It is my concern as much as yours, Gunnar dear. I will not have you take all the blame.”

He worshipped her; she could see it in his eyes. He could forget the difficulties in his contemplation of die miracle of childbirth! His child, his and Carolan’s!

He said falteringly: “My dear… my very dear…”

She turned and kissed him on the lips with a quiet confidence.

She said: “Life has always been difficult for me, darling. You must not be disturbed by this.”

“My … dearest, everything must be done. I am bewildered. Your child, Carolan … and mine! We must get you away from here. But where? Where can I send you? You must not go out of Sydney. It would not be safe…”

She put her arms round his neck then; she was filled with triumph. Her safety! The safety of the baby! That was what concerned him; not the safety of his reputation. She had not been mistaken in him. He was the strong man. the idealist, the master. Crazy ideas began to whirl round and round in her head; wicked ideas. She was so excited that she could scarcely play the part she had set herself to play.

“Gunnar, I have thought of a plan. You shall not be worried at all. I would not have the most wonderful experience of my life spoiled in the smallest way.”

“You are wonderful. Carolan. There is no one like you. So brave… so sensible… so… everything that I could desire in my wife!”

She buried her face in her hands; hot colour had flooded it;

she thought for a moment that he had read her wicked thoughts.

She said coldly, and her voice was muffled coming to him through her fingers: “There is a man who would gladly marry me. His name is Tom Blake. He is a man who has come here to breed sheep. He was taken with me, and I know he wishes to marry me.”

She felt him to be in the grip of cold horror.

“Carolan!”

“Do not look at me,” she cried.

“How do you think I can bear it!”

“I thought you loved me,” he said.

“Ah!” Her eyes flashed as she raised her head.

“You say that, you say it coldly! You thought I loved you! You had good reason to think so, had you not? I loved you … I did not think of the consequences to myself, did I? You know that. You know that I was virtuous before I fell so much in love that I… I…”

That was enough. He was embracing her, murmuring endearments. Did she not know that the thought of her marriage to someone else was unbearable to him? That was why he had said cruel things. But if it was unbearable to him, how much more so was it to her who would have to live it!

“Dearest, do not think of this marriage!”

“But I must, Gunnar, I must! How can I help it? This child of mine, it must have a father. Oh, I know it has … the dearest, best father in the world… but how can I tell the world that you are its father! Gunnar, you do not understand this. To you it is just a vague child. To me it is already living. I am its mother. Gunnar, I tell you this now, and I mean it as I never meant anything else in my life I will not allow my child to be born nameless into a world which takes count of these things. I am wild; I am rebellious. I came to you without thought of what I might do to myself, what hardship I might suffer. I am not sorry I am to have your child; I am glad, gloriously glad! You wanted children, you said. So do I. Madly! Recklessly! That is how I want this child. It means so much to me that I will marry a man I do not love, in order to give it a name.” She watched him in the mirror.

“My child must have a name, Gunnar, no matter what its mother suffers to get it!”

He was heartbroken, crazy with the fear of losing her… and they were both thinking of the woman who lay below.

“Carolan, Carolan, if only it were possible .. if only I could make you my wife …”

“Gunnar, my dearest, you are talking foolishly. You talk of making a convict your wife!”

“If they had sent you over for life even, I would have found a means of marrying you… if only …”

“If only… what Gunnar?”

“There is only one thing that stops our marrying. What else could there be but that I am married already!”

“Oh … were it but possible! But think of your position here in the town, Gunnar. Gunnar Masterman marries a convict. It would ruin you. Why, even were it possible, I would not accept such sacrifice.”

He pulled her down, so that they lay side by side. He said, kissing her fiercely: “Do you think that my position here in the town means anything beside us? Do you think that I would not get to any position I wanted, whatever the handicap?”

“You would, darling. You would! You would do anything, you are so wonderful. Anything you want you could do … Nothing would ever stand in the way… of the things you wanted… you only have to want them badly enough.”

He kissed her again, holding her fast to him. She knew he was thinking that never, never should she go to Tom Blake. She knew that he was thinking of their life together Mr. and Mrs. Masterman of Sydney. No more creeping up the stairs. No more of that furtiveness which he hated. Nothing but the indulgence in that love which had become necessary to him, nothing but growing prosperous, procreating children, which was what the Prayer Book said marriage was for. She let him go on dreaming sensuously for some time before she mentioned the woman downstairs.

Then she said: “Life is ironical. She who could have had a child, would not. Oh, Gunnar, is it not cruel. To think of her… your wife… and not… and not…” She had spoken softly, and he was still in the dream. She said again: “I would not do what she did, Gunnar. Even I, in my position, would not do that! I think it is little short of murder…”

“Murder!” he said, aghast.

“You were not listening. Never mind. I was talking rubbish.”

But he wanted to know.

The baby,” she said, ‘yours and your wife’s.”

There has never been a baby.”

“I mean the one… the one that wasn’t born. Oh… I should not have reminded you. How stupid of me!”

“Where did you hear such a tale, Carolan?”

“It was she who told me. Really, Gunnar, I must say no more … No, no, please do not press me. It was just that it made me feel bitter. She … who is your wife … and deliberately …. Oh, but I will say no more.”

“You must tell me,” he said.

“I know nothing of this.”

“Oh, what have I done! She told me … but it was when she was under the influence of that stuff… she did not mean to tell perhaps… Oh. how stupid I ami Please, Gunnar, do not ask me more.”

“I do ask you, Carolan.” She sensed his growing hatred of the woman who stood between him and his dreams.

“You must tell me.”

“I think she told me not to tell. I did not think she meant you, of course. I thought you would have known. But you see, she takes laudanum; it frightens me sometimes; it would be so easy to take an overdose. Sometimes I think she will, by mistake; it would kill her … she was frightened … frightened of having a baby here; she says it is so uncivilized. She said she would have been frightened in London, but here she was terrified, simply terrified. So she went to that doctor … that ticket of leave man who sells medicines which other doctors will not sell… and he did it for her. She was ill; she nearly died, she said. Do you not see what I mean? She could have had her baby happily … whereas I…”

He did see. There was a cold glint in his eyes now. He hated Lucille, and in his hatred there were no regrets for the child of which he had been deprived; he wanted nothing of Lucille now. He wanted Carolan and his child, which was chiefly Carolan’s child. He was powerless; he did not know how he must act. He was a practical man who had never before been so foolish as to want something beyond his reach.

“It was frightful,” said Carolan, and she shivered.

“When she told me, it seemed to me that what she had done was little else I but murder.” She drew close to him.

“Gunnar, you must not ‘, worry, my darling. Who knows, it may come right.”

He said: “Carolan, you must promise me you will not many that man.”

“How I love you!” she answered.

“I would not have it. I would do anything to stop it.”

“You will not let it be. Gunnar,” she whispered.

“You will stop it… I know you will. You are so clever… so wonderful…”

Something was wrong with the master. Margery knew it! He had a dazed look; his eyes burned; he wasn’t eating his food. Something was wrong with Mistress Carolan; she was paler; her eyes were brilliant. When you spoke to her sometimes she did not answer, and it wasn’t because she was playing the haughty lady either. She wore a black dress nearly all the time a dress with a voluminous skirt, a concealing sort of dress that gave you a clue.

Quite sorry she was for the little ladyship. No snivelling about her. Her lovely head was carried a sure degree higher these days; but there was a pinched look about her mouth. Was she frightened? She wouldn’t admit it! She wasn’t that sort. Now, if only she would confide in old Margery!

She came into the kitchen for the mistress’s bath water. She always made Poll carry it up and take it in. A nice spectacle, Poll, to go into a lady’s bedroom! Why didn’t she let Jin take it? Jin was a strong enough girl. One of these fine days Poll would be upsetting the water all over the stairs, and then there’d be a nice how-doyou-do!

“Get the bath water. Poll.”

“Hello, me love! And how are you today?”

“Very well, thank you. Are you?”

“Now that surprises me, for you’re looking a bit peaky.”

She flinched a little. Suspicious? Come on, tell old Margery.

How long do you think you can keep that sort of thing secret from a pair of knowing old eyes?

“I’m quite worried about you, lovey. You ain’t looking yourself.”

“Please do not worry then, for I am quite well. Poll can take up the water when it is ready. Tell her not to forget to knock on Mrs. Masterman’s door before entering.”

“Not so fast, me darling. I am worried about you. Have a glass of grog. There’s nothing like grog at such times!”

“What times?”

Times when you’re feeling peaky.”

Margery grinned. Not an atom of doubt either; it wasn’t the girl’s looks so much as her manner that gave her away. The master! What would happen now? Men were funny… could be funny… tunes like these. And when a man was as successful as the master, there were always those who were only too ready to pull him down.

Carolan hesitated. Obviously she suspected Margery of knowing. She sat down at the table.

“Jin!”

Jin came with the bottle, sullen as ever. Margery hoped Jin had noticed nothing. Didn’t want her snickering. Not that Jin ever noticed much except men. She was born a harlot, that gipsy.

“There, dearie, drink up. It’ll do you good. You know Margery’s your old friend.”

“Of course I do.” Sharp, acid that was her voice. Keep off! it said. I managed my own affairs. No doubt you do, me lady, but girls in trouble ain’t so beautiful as girls out of trouble, and even men like the master is only human. They don’t like trouble, though God knows they like what leads up to it well enough!

There!” Margery smacked her lips.

“Good, ain’t it? The master is a good master; not another like him in Sydney. We was lucky to get taken into his house.”

There was a chance for her! Margery could have loved her, if she had fallen on her neck and burst into tears. But she didn’t. She was hard as nails and cold as stone.

Anger surged up in Margery. All right, me beauty! All right… She laid a hand on the swelling bosom beneath the black folds.

“You’re filling out, me lovely. You are filling out. Good living agrees with you, ducky. So that’s what a feather bed does for you, eh?”

The girl had whitened.

She said, calmly enough: “Yes, I think I have put on a little weight.” She drained her glass unhurriedly. You had to admire her. What a change, eh, from that snivelling little wretch!

Funny, the two of them, almost together too. But not so funny, for if Margery knew anything of human nature, which she did quite a lot, she would be saying that it was the one that grew out of the other.

Carolan sat there till Poll came through with the water. Then she led the way upstairs.

Carolan said: “Gunnar, I must talk to you. I must talk to you now.”

They were in the hall together. He had just come in from riding. He looked tall and powerful.

He said: “In my room. You go now.”

She went, and in a few moments he was with her.

They know,” she said.

“It is getting obvious. Margery hinted …”

“You must go away from here at once, Carolan.”

“Yes,“she said. “I win.”

“You must see that my plan is the only plan.”

“You must see that mine is.”

“You cannot marry this man.”

“I can, Gunnar, and I will. I will tell him everything. I do not think he will refuse. He will do anything for me.”