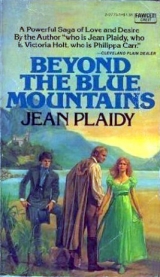

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“You will drink a dish of tea, George? Peg will be bringing it -I told her to, when I knew you were here.”

“You’re too good to me, Harriet!”

“Stuff and nonsense! Because I offer you a dish of tea?” She noticed how thick his legs were; she shivered. He had coarsened since the days of her youth when she had built an ideal and called it George Haredon. She believed the stories about him now; yes, she did, and she would admit it. She was angry;! she was hurt; but the feeling of relief was there all the same. I will send for my niece. Where does the girl get to? A lazier, more good-for-nothing creature I never set eyes on, unless it’s Peg or Dolly. Curling her hair, no doubt Of all the empty-headed girls…”

In a way she was trying to comfort him. She was quite sorry for him almost as sorry for him as she was for herself. It was Kitty she blamed; just as she had blamed Bess. You didn’t blame men for being what they were; you blamed women for helping to make them so.

She left him sitting, and went indoors.

“Tell my niece to come down to the garden,” she instructed Peg.

“Tell her I particularly wish her to come.”

Kitty came. On her lovely hair she wore a hat which shaded her eyes and shielded her face. She greeted the squire coldly. Harriet was amazed to see that there was a certain humility if the manner of his greeting to her; she had never seen George Haredon humble before, except perhaps when he was very young and so much in love with Bess. Kitty was almost haughty ridiculous creature, giving herself airs! How she would like to beat Kitty until the blood ran! Once, before the days of Peg an Dolly, she had almost beaten one of her maids to death; a chili of fifteen, a trollop if ever there was one! Got herself with chili by one of Squire Haredon’s grooms. And Harriet had beaten her and beaten her and when she grew big had turned her out. No one knew what had become of her after she left the Bridewell She was probably leading the life most suited to her nature. Well, that was how Harriet would have liked to beat Kitty … only Kitty was no child of fifteen; she was a strong young woman, and probably would not allow herself to be beaten almost to death.

The squire scarcely touched his tea, and he forgot to compliment her on the excellence of her seedcake. He was discomfited, and all because of his carnal desire for a girl who would be a disgrace to his house; why, she had no idea even how to make raspberry jam.

The squire took his leave. Kitty carried in the tea tray and, in her agitation, broke one of the cups.

Harriet screamed at her: “You lazy, careless creature! I wish I had never clapped eyes on you. A pity you did not stay in London where you belonged. Doubtless you would have found the protection of some fine gentleman, as your mother did so admirably for herself!”

Once Kitty would have laughed at that; the words would not have hurt her at all. But now she was jealous of her virtue; Darrell was involved. Her aunt was suggesting that this love she was so willing, so eager to give to Darrell, could have been any fine gentleman’s in exchange for his protection. She turned on her aunt with fury.

“You wicked woman!” she cried.

“And more wicked because you think you are so good. I will not stay here; I shall go away.”

“And where will you go, Miss?”

Kitty faltered. She was ready to blurt out: “I am going to be married. I shall go with my husband.” But even at that moment, hot tempered as she was, she realized what folly that would be.

“I … shall go one day!”

Harriet laughed. And for one moment she knew that her place in the squire’s bed had occupied her imagination more than her place at the head of his table; and she knew that she was a disappointed woman, and felt an insane desire to go to the still-room and smash every one of those neat bottles. She tried to calm herself; but she could not. In a moment she would be sobbing out her disappointment. Angrily she strode to the wall where hung that whip with which she had beaten the fifteen-year-old trollop who had been so free with one of George’s grooms; she seized it. and her fingers were white with the tension of their grip upon it.

“You … you …” she cried, and there was almost a sob in her voice.

“Do you think … I don’t know … your kind! Do you think I haven’t seen the way you led George Haredon on? I believe you let him into your room at night… perhaps others. I believe …”

The pictures were now forming into words, and she must stop herself for shame she must! But Kitty stopped her. Kitty’s eyes were blazing. She walked straight towards her, raised her hand as though to strike her. then dropped it and said in a cold low voice: “You wicked, foul-minded woman! You and George Haredon would make a good pair, that you would.” And she threw back her head so that the fine white voluptuousness of her throat could be seen to advantage. Then she laughed and went swiftly from the room.

Kitty stayed in her room until close on eight o’clock; then silently she left her Aunt Harriet’s house and went to the wood. Darrell was waiting for her in that spot where the trees were thickest. She clung to him, crying.

He said: “My dearest, what has happened?”

She cried out: “I cannot stay here; it is hateful! My aunt thinks hateful things of me. Darrell, she is a cruel woman, for all her piety. How I wish that we were in London and that my mother was alive; she would have helped us.”

He said: “Listen, my lovely one, my darling Kitty, listen! You will not have to stay. Today I have heard from my Uncle Simon.”

Her smile was more brilliant for the tears that still shone in her eyes; her joy the greater for the fear it displaced.

“You have heard… He has said …?”

“He says we must marry. He says we must leave this place and go to London.”

“When… oh, when?”

Darrell hesitated.

“There must be preparations, dear one. In a month, say. Kitty, can you endure this for just one month longer?”

“A month! It is a long time. I have not yet been in my aunt’s house three weeks, and it seems three years. Cannot we go now …this minute?”

He laughed at her impatience. They sat on a bank, and the grass was soft and cool, and the trees made a roof and shut them in in.

“If we could … oh, if we could! But no, dearest, we must do what Uncle Simon says. He is going to make preparations for us. He is going to take me into his business. He is going to find a house for us, and that will take a little time. Then, my darling, we shall take the coach and go to London, and when we get there a priest will marry us and we shall be happy, and all this will seem like a nightmare.”

“Darrell! It is wonderful. How I love your Uncle Simon!”

“You must love no one but me!”

“I should not, of course, except our children, Darrell.”

“Our children!” he said.

How the birds mocked overhead! He thought of their lovemaking on the branches of the trees, building their nests and bringing up their young. It was like a miracle it was the miracle of living. And how much more wonderful to be a man and love a woman, a woman such as Kitty!

She had lain back on the grass now, and her eyes made the sky he could see through the branches look grey. Lovely she was, with her white bosom and fair neck and her hair a little tousled now, and her hands that seemed to be reaching to him.

She was seductive and irresistible: and because she knew it, and because she, Eke the birds, was’ mocking that cautious streak in him, he could no longer bear it. He threw himself down beside her and buried his face in the whiteness of her shoulder.

She said: “What a lovely end to a horrible day! Darrell, that hateful Squire Haredon asked me to marry him today.” Darrell drew himself up and looked at her with horror.

“Yes,” she went on.

“Oh, darling, don’t look so frightened! I told him I hated him. He came upon me when I was in the summerhouse, and tried to keep me there and force his horrible lovemaking on me. What a beast he is, Scarcely a man, I think -and how I hate the noisy way he breathes! You should hear him drink his tea. and it is as bad with coffee or chocolate. Hateful! Hateful! And I told him so.”

He leaned on his elbows. Here in the woods was perfect peace and happiness, but outside terrible things could happen. He would write again to Uncle Simon; he would say a month was too long or perhaps they would go to London without saying anything.

“He is powerful hereabouts,” he said.

“If he knew you loved me, he could rake up some minor charge against me.”

“That would be wrong… that would be cruel…”

“It is a cruel world we live in, Kitty.”

“But how gentle you are, Darrell, Perhaps that is why I love you. All the time you think of me; not what you want, but what is best for me. I see it, Darrell, and I love you for it. You would die for me, I know; I would for you too.”

“I do not want us to die, but to live for each other,” he said.

“You are clever with words and how I love you! Let us not think of Squire Haredon and my Aunt Harriet and your Uncle Gregory, nor of the cruel world we live in. How lovely it is here! How quiet. We might be alone in the world; do you feel that, Darrell?”

Her lips were parted. She was her mother and the blacksmith’s daughter. She loved; she loved passionately and recklessly; she was the perfect lover because love to her was all-important. There was no room in her mind for tomorrow; let others think of that.

He heard her laugh a little mockingly, as he thought the birds laughed invitingly, irresistibly. He felt the blood run hot through his veins. He was aware of the letter he had had from his Uncle Simon, crackling in his pocket when he moved.

He put his mouth on hers; her arms were about him. Only a month, he thought desperately; everything was really settled.

Inside the wood it was heaven. Outside was the cruel world. But did one think of the cruel world when one was in heaven?

Meetings in the wood took on a new joy. Kitty lived for them, scarcely aware of the days. Harriet watched her slyly, watched the rapture in her eyes, and thought, I believe she will marry the squire after all. I believe all that talk of hating him was coquetry. Was that how Bess did it?

And because the greatest terror of her life was that it might be discovered that she herself had contemplated marriage with the squire, she talked to him of Kitty.

“I felt, George, that right from the time you set eyes on her she reminded you so much of Bess that you had quite an affection for her.”

What a keen glance he had shot at her from under those bushy eyebrows of his!

“You’re a fanciful woman, Harry!”

“I’m a woman with my eyes open. Why, sometimes I could almost feel it was Bess herself smirking before her mirror, curling her hair and making herself a hindrance rather than a help about the house!”

He laughed at that.

“So that’s how it is, Harriet.”

“Mind you, if that is what was in your mind, and she was to know it and make a pretence of flouting you, I wouldn’t take her seriously. She’s a coquette; a born one, and made one by that mother of hers. She’s the sort who would want to lead a man a dance…”

There! That had him. He was puzzled. He was beginning to think that Harriet had turned matchmaker. And how excited those words of hers made him! He was ready to grasp any shred of hope, so badly did he desire the girl.

His visits to the house did not diminish. Kitty, though, hardly =seemed aware of him. She passed through the days like a person in a dream, the passion in her making her long for the evenings. Meetings took place earlier now, for the days were getting shorter; so they had longer together. What good allies she had in Peg and Dolly! Sometimes she stayed in the wood until close on midnight, but Peg and Dolly never failed to watch for her return and creep down from the attic to let her in. The days passed. Darrell heard from his Uncle Simon again. Uncle Simon was enthusiastic; he longed to see the beautiful girl whom Darrell described so eulogistically; he longed to score off old Gregory. He was getting ready for them; he would be ready for them very soon.

“Next Monday,” said Darrell, ‘we will take the coach. We will meet here at midnight on Sunday: we shall have to walk into Exeter. We shall catch the very first coach, and we must take care not to be seen.”

“Monday!” cried Kitty gaily.

“Oh … in no time it will be Monday!”

Darrell was excited, making plans.

“One day this week I shall go to Exeter for my uncle; then I shall book our places on the Monday coach.”

“It’s wonderful! Wonderful!”

“And,” cautioned Darrell, ‘a great secret, to be told to no one.”

“You can trust me for that, though I should have liked to say goodbye to Peg and Dolly.”

“You must say goodbye to no one. If this went wrong, Kitty She laughed at him.

“How could it go wrong?”

She was so full of joy that she wanted everyone to share it. She worked hard in the garden; she tried to please Aunt Harriet; she even had a brief smile for the squire. She gave Peg a scarf and Dolly a petticoat. She just wanted everyone around her to be happy.

She met Darrell as usual on Wednesday evening. What a glorious evening it was! The air soft and balmy, and no breeze to stir the branches of the trees.

Darrell said: “I shall be thinking,of this all the way to Exeter tomorrow. When our places are booked it will seem as though we are already there. Kitty! You must not go back looking as happy as you look, or someone will guess!”

And she laughed, and they embraced; and then they lay there, ” talking of London and the future.

It was past midnight when Kitty returned to her aunt’s house, but Peg, wearing her scarf, let her in.

All next day she was absent-minded. Harriet noticed.

“What has come over you, girl?” she demanded.

“You are not even as bright as usual!”

Kitty smiled very sweetly; she could afford to be patient with Aunt Harriet. Her thoughts were all with Darrel, riding to Exeter on his uncle’s chestnut mare.

She went to the wood that evening. He did not come. She returned home a little subdued. Why, of course he had not got home from Exeter; that was the reason he had not come. He had said he might have to stay the night if he could not conclude his uncle’s business, but would certainly be home on Saturday.

On Saturday she was waiting for him. How quiet was the wood! She had never noticed that so much before. There were few birds now and the leaves were thick, some already beginning to turn brown at the edges. A gloomy place, the wood, when you waited for a love who did not come.

She was anxious now: she was frightened. What could have happened to detain him? Business? Suppose he did not return by Monday; they had made no plans for such an occurrence. What should she do? Go to Exeter alone? But how could she take the London coach alone? She would not know where to go when she arrived. She had not the money to pay her fare.

She ran through the trees; she gazed up and down the road. Once she heard the clop, clop, of horses’ hoofs, and when the sound died away, the disappointment was intense. Lonely and desolate, she returned to the meeting place; he was not there. It grew dark.

Why had he not come? Here was Saturday, and he had not come.

Sunday was like a bad dream from which she was trying desperately to escape. Perhaps he would send a message; he would know how frightened she must be, and he had ever been mindful of her comfort and her peace of mind.

On Sunday evening she went to the wood, and still he did not come.

Peg and Dolly crept into her room and found her sobbing on the bed. They eyed each other sadly. Perhaps they thought it was unwise to trust a lover too far. They cried with her. It was a cruel world, they said.

Monday, which was to have been a day of great joy, set in with teeming rain, and Kitty’s heart was mote leaden than the skies.

It was Peg who got the news. She kept it to herself for a while: then she told Dolly. They cried together: they did not know what to do. But if they did not tell her she would discover in some other way. So in the evening of that black Monday they told her. They tapped at her door and went in to find her sitting at her window, her lovely face distorted by grief, her beautiful hair in disorder.

“A terrible thing has happened.” said Peg.

“… to Lawyer Grey’s nephew who went to Exeter,” added Dolly. Though.” put in Peg quickly, ‘it may be a story. Such stories are.”

Dolly shook her head sadly.

“He was seen to be took!”

Kitty stared in bewilderment from one to the other.

“And his horse was left there for hours, pawing the ground,” said Peg sadly.

‘ Twas in a tavern… in broad daylight. The wicked devils, to take a man!”

Kitty looked at them wildly. The unreality of the day had faded, and stark tragedy was all that was left.

“What!” she cried.

“What is it you are saying?”

“He went in for a glass of ale and maybe a sandwich.”

“He was not the only one that was took.”

“Tell me … tell me everything you know,” pleaded Kitty, suddenly calm with a deadly calm.

“Such news gets round,” said Peg wretchedly, shaking the tears out of her eyes.

“There were them that saw it. The villains burst in… he was not the only one that was took.”

Kitty stood up and gripped the rail of her chair.

“Peg …” she said.

“Dolly …” And her mouth quivered like a child’s.

Dolly threw herself down on the floor and put her arms round Kitty’s knees, burying her face, in her gown.

“It was the devils as folks call the press gang. Lurking everywhere, they be, to take our men to the ships.”

Kitty stared blankly before her.

Peg said again, and then again, as though there was a grain of comfort in the words: “He were not the only one they took.”

Kitty was numb with misery; listless, without spirit.

Harriet said: “Are you sickening for the pox, girl?” And she examined her body for some sign.

She went about the house, doing just what she was told. Harriet thought, I’m shaping her: she’s improving. And when she knelt on the coconut matting beside her bed at night, she offered thanks for the change which had come over her wayward niece.

The squire was a more frequent visitor than ever. Kitty did not move away when he sat beside her on the garden seat. She listened to what he had to say, and gave him a listless yes or no.

The squire said: “It is quiet for you here, Kitty. Day after day going about the house and the gardens with your aunt it is no life for a young girl. Now look here, we do a bit of entertaining now and then up at Haredon; why, sometimes I’ve got a houseful. Would you come, some time like that, eh, Kitty?”

She said: “I am all right here, thanks. I do not wish for a lot of people round me.”

“Then a small party. Just you and your aunt… I’d like you to get to know my children.”

She smiled.

They are very charming,” she said.

“I have seen them driving with their governess.”

From under his bushy eyebrows he looked shrewdly at her. What did she mean by that? Was she telling him she knew about his relationship with Jennifer? She was clever of course, this girl; clever as Bess had been. And he had never been sure what Bess might be thinking; why right up to the end he had believed she was going to marry him, and all the time she must have had it in her head to run away with that actor fellow.

Women knew a lot about each other though. Harriet had said the girl was coquetting with him, leading him on. He liked to think that. He liked being led on. Cool and virtuous, holding him off, telling him she couldn’t bear him, just to get him hot enough to offer marriage. He had offered marriage; and she was still holding him off. She had been brought up in London Town where they were devilishly sly, and clever too and, by God, he liked them for it! There were plenty of country wenches ready to fall into his lap; but Kitty was apart from that. Kitty was Bess, and Bess had haunted his life. Now here was compensation he couldn’t have Bess so he would have Kitty.

Sitting beside her, it was all he could do to hold himself in check. She had changed now; not the spitfire any more; calm, sad. wistful… womanly, you might say. She appealed now to something sentimental in him, as well as to his senses.

“I’ll get rid of the woman!” he said, just in case she was jealous of Jennifer.

“She was never much good as a governess.”

“Oh! She looks capable enough.”

Disdainful! It is nothing to me if she is your mistress! That was what she meant, confound her! He wanted to slap his thighs with delight. He knew the signs; he was like a small boy looking up at luscious fruit just out of reach, with the knowledge that sooner or later its very ripeness would make it fall right down into his hands.

“Capable__oh, yes. But why bother ourselves with servants on an afternoon like this!”

“Now, Kitty …” His arm slid along the seat, but immediately she stiffened. He let his arm drop. No sense in rushing things; after all, he was not wholly sure that Harriet was right.

“Well, what about this visit of yours to Haredon?”

“You would have to arrange that with my aunt, would you not?”

“Why, of course, Kitty, of course!” His face was screwed up with delight.

Harriet came across the lawn. Her lips were pursed; they were always like that in repose. Peg followed her with the tea tray.

“A lovely day, George!”

“A perfect day,” said George.

Daintily Harriet poured the tea. George took his and pressed his back against the seat. He was amused at himself, sitting here drinking tea with two women. He could have done with a pint of good ale. Still, here he was, doing the polite, and pretending to like it. He looked at the stiff figure of Harriet poor woman! From her his gaze turned to Kitty and his eyes were glazed with desire. But soon the fruit would fall into his hands; so much of the rebellion had gone out of her that it seemed as though the branch was already bending down to him. But he must go cautiously; he would say nothing now about this visit she would pay to Haredon. She was full of whims and fancies; she might refuse yet!

He sought for a topic of conversation.

“Lawyer Grey is in a fine to-do about that nephew of his!”

Kitty sat up straighter, but neither Harriet nor the squire noticed that.

“So I heard,” said Harriet.

“A few years at sea will do the boy good. Roughing it never hurt anyone.”

“I do agree,” said she; ‘but will not Lawyer, Grey try to do something about it?”

The squire laughed.

“What can he do? Fight the press gang? No! Mark my words, the young man’s well out at sea by this time.”

“He’ll come back a man,” said Harriet.

“If he comes back at all,” said the squire.

“There are dangers enough to be met with on the high seas.”

Kitty lay in her bed and stared helplessly up at the ceiling. She was not thinking of Barrel] now; she could think of nothing but the girl whom Aunt Harriet had whipped almost to death.

This could not be… not in addition to everything else! When she had heard them talking so callously down there in the garden, she had said to herself: I will wait for him! I will wait! And she had meant that if there were to be years and years of waiting, still she would wait. But those years had to be lived through, and how could she live through them, penniless, with a baby to care for?

How cruel was life! Darrell had been so anxious that no harm should befall her and it was only because they both believed so fervently that they would ride to London together that he had released his passion; and once he had done that he had been unable to stem it. She was shivering, but when Peg and Dolly peeped in to see how she was, they found her unnaturally flushed.

“Why, bless you, Miss Kitty, you have a fever.” said Peg. She cried in panic: “Do not mention to my aunt that I am not well.”

She got up and bathed her face. It was a good thing that Harriet, who had never been ill in her life, did not believe in illness. Unless it was a leg that was broken or a wound that she could see, she thought it was sham.

Kitty went about her tasks outwardly calm, inwardly in a tumult. She was forgetting her love for Darrell in her fear for herself. A terrible thing had happened to Darrell; but a still more terrible thing had happened to her.

If only her mother were here, she would know what to do. Nothing would ever turn her mother from her. She talked to her mother in her thoughts. You see, Mother, we loved each other so much, and we were going to London to be married. If only he hadn’t gone to Exeter! If only he had stayed here, I should be married to him; we should be with his Uncle Simon in London, and we should be so happy because we should be going to have a child. But now there is no one to help me, Mother. Aunt Harriet is cold and distant, just as you said. She would never have done this thing which I have done; therefore she would think me wicked to have done it. There was a poor little girl from the workhouse, and she almost beat her to death. But what happened to her afterwards … when Aunt Harriet turned her out! That is what I think, Mother; that is what I cannot stop thinking.

And the very thought of her mother’s face, lovely though ageing, and full of lazy kindness, soothed her. She would have understood; but she would have been practical too. She would surely have said: “We must find a husband for you, darling.”

“Mother! Mother!” prayed Kitty.

“Do something for me. Help me! Give me some sign that you know what has happened to me, and tell me what I can do.”

She asked Peg and Dolly about the girl who had loved a groom. They had not known her but they had heard of her.

“Tis a terrible thing to happen to a girl,” said Peg; and she and Dolly were silent for a long time thinking what a terrible thing it was to happen to a girl.

Kitty wanted to shout: “It has happened to me!” Something restrained her; she thought it was her mother, watching over her, restraining her. No one must know__yet… no one at all.

She and her aunt went to Haredon for a few days; the squire had sent the carriage for them.

A lovely house, Haredon; it had been built by a Haredon in the reign of Queen Anne. Harriet sat, lips pursed, as the carriage turned in at the drive. The gracious elms, the grey walls of the house had always filled her with pleasure. She thought of the land round Haredon, and especially the orchards; she thought of the staff of servants and the joy of running the place.

The squire came out to meet them, and from a window Jennifer Jay watched them.

Colour burned in Kitty’s cheeks; her eyes were brilliant. Never, thought Squire Haredon, had she looked as beautiful as she did here in the setting which would soon be hers. She liked the house; perhaps she liked it so much that she was ready to take him, since he went with the house.

You wait! he thought. You wait, my beauty! And his fingers itched to seize her; and as they walked into the house he put his hand on her shoulder and gripped it hard; she turned her head and smiled at him, with her lips parted and a look of promise in her eyes. His hand slipped to her waist and touched the warmth of her bosom. She did not move away from him, and as they entered the house she was still smiling.

Dolman, the butler, brought drinks into the library. The squire touched her glass with his; she could see the veins standing out on his forehead knotted they were, and blue, as if ready to burst. She felt more comforted than she had since she had lost Darrell, and it seemed to her then that this visit was her mother’s answer to her prayers.

“I want to show Kitty round the place,” said the squire, smiling into his glass.

“I am proud of Haredon, Kitty.”

“And rightly so, George,” said Harriet with no trace in her voice of the wistfulness she felt; ‘it is a place to be proud of.”

“Thank you, Harry. Now, Kitty!” He smacked his lips and licked the wine from them, and his eyes never left her.

“Come now.”

They left Harriet in the library with the squire’s eldest cousin who had come to play hostess, and went over the house alone. It was indeed a beautiful place, so big that Kitty felt it would be easy to lose oneself in it. There were tall windows, ornate ceilings and deep window seats. Now and then Kitty heard the sound of footsteps hastily scurrying away; once a mob-capped serving maid, unable to escape in time, blushed hotly and dropped a deep curtsy; and in his free and easy way the squire made her stand before them, and he introduced Kitty as though she had already agreed to share his home. He seemed younger then, and she liked him better than she had ever liked him before. This was his castle and he was the king; he was a showman watching the effect on her of his treasures.

“Do you like it, Kitty?”

“It is very grand!”

“Big though. Big for one man to live in… all alone.”

She could laugh at that.

“As far as I can see, you are far from alone … here.”

“You pick me up sharp, Kitty!” And he looked as if he liked being picked up sharp.

They were in the galleries, looking at portraits of the Haredon family.

“Do you think I take after them, Kitty?” he wanted to know, thrusting his face close to hers.

“I can see you better, not so close,” she said, and he laughed and drew back. Wasn’t that just the sort of thing Bess would have said! It was like having Bess here again. He thought of gripping the girl’s shoulders and kissing her, and hurting her hurting her for all the years he had been unable to forget Bess.

“Yes,” she went on, ‘there is a resemblance.”

“Ah!” he said.

“That’s how it is with families; you are the spit of your mother, Kitty. There was a time, you know, when I was very fond of your mother.”

“Most people were fond of her!”

That was the trouble, Kitty! That was the trouble.” He narrowed his eyes. He thought, by God, if you try any tricks with me, I’ll well nigh kill you! Bess fooled me I’ll not stand for that treatment twice in a lifetime.

She said: “I want to see the children.”

Jennifer stood up as they entered. She had been by the window, stitching something. He could see how violently her heart was beating under her tight bodice: she must learn to behave; more tantrums and out she would go; she gave herself airs because once he had found her amusing.

“Where are the children?” he asked curtly, and he wanted to give her a slap on the side of her face for her insolence.