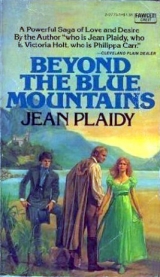

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

He sat, sprawled out in her drawing-room, and the clock ticked on. Inwardly he laughed, and was soothed for the slights he had suffered from Bess and from Kitty. He sat on, drinking elderberry wine until the clock struck ten.

“Good gracious me!” said Harriet.

“Did you hear that, George? Ten of the clock, I do declare, and you with that ride home before you!”

“The ride is nothing to me, Harry.”

“But I was thinking of what you might meet on the road. George. I do declare the roads get worse and worse.”

“Bah! I would like to see the man who would dare ask me for my purse! He would not get away with it and his life.”

She eyed him with a wistful softness.

“Doubtless you would be reckless, George.” she said softly, ‘but that does not ease my mind.”

“By the Lord Harry!” cried the squire.

“Are you going to offer me a bed?”

He could scarcely stop the smile curving his lips. It was such a good joke that; but she did not appear to hear it.

There are beds and to spare in this house,” she said.

“I will tell Emm to prepare a room. Emm!” she called.

“Emm!”

“My good Harriet,” laughed the squire, ‘you’re to put all such thoughts out of your head. A ride in the dark has no terrors for me, I can tell you. I enjoy it!”

“I know, George. I know.”

He felt himself aglow with her admiration. He was glad he had come; he was glad he had stayed. Why let Kitty humiliate him? Why have let Bess? There were women in the world who thought very highly of him.

Emm appeared in answer to the call. Candlelight softened her, hid the grime of her. Her eyes were large and soft like a fawn’s eyes.

Harriet hesitated. The squire roared out: “Get a lanthorn, girl, and light me to the stables!”

Emm said: “Indeed I will, sir!” and went out.

The squire rocked backwards and forwards on his heels, smiling at Harriet, well pleased with himself.

“Good night, Harriet, m’dear.”

“Good night, George. It has been most pleasant.”

“We will repeat the pleasure, Harry. No, no! You shall not venture out into the night air. I’ll not allow it. There is deadliness in the night air, Harry.”

Ah. he thought, laughing, and magic tool Starlight could throw a cloak of beauty even about such as workhouse Emm.

Emm appeared in the hall, holding a lanthorn in her hands.

“Come you on, girl,” he said.

“The hour is growing late.” He did not look at her, but he was aware of every movement of her body as she passed him.

“Goodbye, Harriet.”

Harriet stood in the doorway. The lanthorn, like a will-o’-the-wisp, flickering across the grass on its way to the stables.

“I shall not move till you have shut yourself in from this treacherous night air, Harriet.”

“George, you are too ridiculous!”

“Is it ridiculous then to care for the health of one’s friends?”

She closed the door. She thought how charming he was, under the right influence. What a certain woman could have done for him!

The lanthorn flickered against the darkness of the stables. It was a lovely night. There was no moon, but a wonderful array of stars. They seemed bigger than usual, like jewels laid out for show on a piece of black velvet. He began to hurry across the grass.

“Emm,” he said softly.

“Emm! Wait for me!”

She was beside him, and as he laid a hand on her shoulder, she stepped back a pace. Sly, silly girl, he thought. But he was in no hurry; he preferred a little dalliance.

He said: “Lead the way, girl. Lead the way!”

And she went before him, holding the lanthorn on a level with her youthful head. His eyes were fixed upon her appraisingly; all young creatures were beautiful by starlight.

“You are a nice girl, Emmie,” he said.

“Often have I noticed that.”

She did not speak, and he roared out: “Did you hear me?”

“Yes, sir,” she said, her voice trembling.

“Thank you, sir!”

“You like me, Emmie, don’t you?”

“Oh, yes, sir.”

She had a grace, this girl; the fawn-like quality was very much in evidence. She seemed to him to be poised for a fleet and startled withdrawal.

Damn it! he thought, his veins swelling. She was willing enough. Brown as a berry, and ripe as plums in September. He would have fun with her, right under Harriet’s prim nose.

“Emm!” he said.

“Put that plaguey lanthorn down, and come here.”

She came and stood cautiously before him. He put out his hands and he felt the quiver run through her.

“Now, Emmie, girl, nothing to be afraid of, nothing to be afraid of, eh?”

He talked soothingly as he talked to his horses.

“Come on, Emmie girl; come on, now!”

Then he seized her and kissed her, and felt his blood run hot through him. She was not too clean, and she smelt of the dinner she had cooked the dinner he had eaten with Harriet.

He was exultant, laughing at Bess and Kitty really, getting the better of them in some queer, subtle way.

But Emm was panting; she wrenched herself from his grasp suddenly; she was as agile as a young monkey.

Damn her! he thought. Wanted chasing, did she? These workhouse girls were giving themselves airs indeed! By God, did she forget he was the squire, about to confer an honour upon her! Had she been listening to that other one, that Janet who was saving up her virtue for some blundering farm labourer? No, no! She wanted a chase some of them did; liked to lead a man a dance. But that was the ladies. The workhouse girls were giving themselves the airs of ladies these days! She would lead him a dance, make him chase her over the garden, taking good care not to escape from him, and be caught conveniently when they had both had enough of the chase; and laughing and panting, and perhaps biting and scratching, she would give way. Well, well, he was in a good humour and the night was before him. He set out after her across the lawn. She was fleet though. She was in the house. She had shut the door on him. And what could he do, confound the girl, but tap timidly for fear of Harriet’s hearing, and then when she said from the other side of the door, “Please go away!” he had to plead: “Emm! Emmie, girl. What is wrong with you? Come out, I say! Come out, I tell you!” But she did not come. And how could the squire stand pleading at the back door with a girl from the workhouse!

Wild fury possessed him. It was all he could do to restrain himself from breaking down the door. That would be sheer folly, of course. He had to do better than that. By God, did the girl not know that he could have her brought before him, could have her whipped in public, could have her sent off to a convict ship … and, yes, could no doubt have her hanged if he cared to! He was the squire, was he not? A magistrate! A Justice! He felt the veins in his head would burst: his eyes burned with his anger. Doubtless the slut had committed many a crime which only had to be discovered. By God, he would show her! But there was nothing he could do this night. He forced himself to walk slowly back to the stables, trying to quell the angry beating of his heart. He did not want to be bled again… he must not work himself into such a fury over a mere workhouse slut. But it was not the workhouse slut well he knew that it was Bess again, jeering at him … Bess and Kitty, confound them! a, It was good to feel the horse between his knees, responding to every pressure a noble creature who knew his master. He had no wish to go home; he rode for miles, galloping and cantering across the fields, through the country lanes; and when he had had enough it was past midnight, and when he reached home it was nearly one o’clock.

He himself rubbed down his horse, for though he was a stern master he was a good one. Then he went into the house and poured himself a glass of whisky.

“I will get the taste of Harriet’s plaguey concoctions out of my mouth!” he said, and he laughed afresh at Harriet’s feeling for him, and drank more whisky, for there was nothing like whisky for keeping a man’s spirit up and he was going to Kitty. He had stood off long enough, and, damn it, he had to get the taste of that bit of foolery with the workhouse chit out of his mouth as surely as he had to get rid of the taste of Harriet’s wine.

He went upstairs. The door of her room was not locked as he had half expected it to be, but if it had been he would have had it down; he was in that mood.

“Kitty!” he called.

“Kitty!”

There was no answer.

“Ha! No use pretending to be asleep, girl.” He sat down on the chair by her dressing-table.

“Curse this plaguey darkness!” he said.

“Where do you keep your candles, girl? Get out of that bed and light one. I have had enough of your lady ways__Tonight I am going to show you that I have had enough. From now on things are going to change in this house…”

His voice was a little shaky. The mood of sentimentality was creeping in on him. In a moment he would be saying: “Kitty, let us start again … Could we, girl? I will forget what you have been, and you forget what I have been …”

He wanted Kitty. Damn it, he was getting on in years. He had done with the chasing; he wanted to settle. A man felt like that -settle and look after the children. And perhaps have more children. Three was no family for a man. More children like little Carolan. Kitty’s children that was what he wanted Kitty’s and his this time.

“Kitty!” he said, his voice soft and pleading.

“Kitty, girl.”

He groped his way to the bed and felt for her. It took him some seconds to realize that the bed was empty.

He was shouting, rousing the household.

“Here! Everybody! Where the hell is everybody! Come here at once, I say!”

And while he stood there, listening to his own voice he thought: By God, she is paying a midnight visit to a lover! What a fool I am going to look! By God! By God, I’ll make her pay for this!

A fool he was, a fool, to act without thinking. He imagined the tittering of the servants after this. If he heard any tittering, saw any sly glances, he would have them whipped, that he would.

Mrs. West, the housekeeper, came first, her dressing-gown pulled around her, her teeth chattering, her candlestick shaking in her hand.

“Where is your mistress?” he barked at her.

Mrs. West peered at the bed.

“Tis not been slept in, master!”

“I see that. Do you think I am blind!” He looked at her narrowly; she had always been Kitty’s friend, he knew. Was she hiding something?

“Look you, woman, if you have any idea, any idea whatsoever, of where your mistress is, you had better tell me at once or it will be the worse for you. Do you hear me?”

“I have not the faintest idea, master.” He knew that the woman was speaking the truth. Other faces appeared in the doorway, among them Jennifer’s. Jennifer was smiling secretly. She was thinking, as he was thinking, that Kitty had gone out to meet a lover. In a moment he would be slapping that secret smile from Jennifer’s face.

He said: “Call her maid!” and Jennifer went away and brought in Therese. Therese’s black hair hung in two plaits and her black eyes glittered.

“Where is your mistress?” demanded the squire. Therese looked towards the bed and lifted her shoulders in surprise.

“That I do not know. Monsieur.”

“Come,” said the squire, I think you do know.”

“But no. Monsieur!”

“Did you not dress her for an outing?”

“But no, Monsieur! She retired early this night. It was ‘cad-ache!” Therese held her own head and closed her eyes, then opened them and lifted them to the ceiling. Jennifer laughed. The squire said: “Get outside, all of you … Except you!” he added to Therese.

He did not watch them go, but he heard them, shuffling out, and he cursed himself for a fool to have aroused the household like this.

“Now,” he said to Therese, ‘no secrets! It is no use telling me that you did not share your mistress’s secrets and take part in her intrigues.”

“Oh, but no, no, no, Monsieur! Intrigue? What is he?” Plaguey foreigner! She did not understand when she did not wish to. Neat she was too, and cheeky with her flashing black eyes; and not too old. Her gesticulating hands were beautifully shaped.

“Damn it!” he said.

“Get out. I will speak to you in the morning.”

She went out daintily, and he sat alone in the bedroom. He would wait here for Kitty’s return, and when she came in he would take his riding crop to her. He had been soft. It was no way to treat a woman, to be soft with her. He would punish her now, in the way that would hurt her most. He would beat her white skin until the blood ran; then she could show that to her lover, and they would say he was a brute, but they would know he was master. He would beat her for what she had done to him, and what Bess had done to him; he would beat her for a hundred insults, even the one he had received tonight from a workhouse brat.

Jennifer came silently into the room. She stood close to him, thin and tall; the candlelight on her slanting eyes and pointed face made her look like a witch.

“George…” she said humbly.

“Get out!” said the squire.

She knelt beside him and lifted her face.

She said: “I have always been faithful to you … We used to be happy.”

By God, he thought, she has. And I believe we were happy in a way.

“All right, Jenny,” he said.

“All right.”

“George,” she said again, a high note of excitement in her voice, ‘why cannot we try to be happy once more?”

He was so tired; he let his hand touch her hair. She nestled close to him. He thought of past scenes; she was a passionate, strange creature, this Jennifer; he had liked her well enough once; she had been a great contrast to cold Amelia. There had been a time with Jennifer when he had almost ceased to think of Bess.

“All right, Jenny,” he said again.

Closer she came, and he smelt gin on her breath.

He said: “You have been drinking, Jenny!”

“No,” she lied. And he thought: Damn her. I cannot trust even Jennifer!

She nestled close to him. She was fuddled, too fuddled to think clearly. She tried too quickly to press home her advantage.

She said: “Oh, George, if you could know everything that has gone on in this room! If I could tell you!”

“Why the hell did you not tell me?” he demanded.

“How could I … of the mistress? There was not one lover, George. There have been scores!” She tittered. He hated tittering women.

“There are things I might tell you, George, if you were to ask me.”

Vivid pictures crowded into his mind, and Kitty figured largely in them all. Red mist swam before his eyes. He was so wretched and miserable and lonely, but Jennifer was too foolish to help him; a drunken sot of a woman she was nowadays. He stood up suddenly and sent her sprawling. He laughed at her and touched her with his foot, not violently, but contemptuously.

“Get out, you drunken slut,” he said. Jennifer got up; she stood before him pleadingly.

“Get out!” He put his face close to hers.

“And do not let me see you in this state again. It is bad enough to have a harlot in my nursery. I will not have a drunken harlot, do you hear!”

She crept out of the room.

The candle guttered. The clock ticked on. And as he sat there he knew that Kitty was not coming home.

The dawn was beginning to creep into the sky when he remembered seeing her that afternoon with her daughter. He went suddenly cold. Had she taken Carolan with her? Hastily he went to the child’s room. With great relief he saw that she was still there.

He sat heavily on the bed. He could just see her face in the early dawn light a child’s face with a smudge of lashes against her pale skin, very sweet, very innocent.

He shook her.

“Wake up, girl! Wake up!” She awoke startled.

“Oh …” she said, ‘the squire!”

He frowned. He had told her she must call him Father, had threatened to whip her for not calling him Father; and it was only in unguarded moments that she slipped back into the childhood habit of calling him the squire.

“Carrie,” he said sternly, ‘where is your mother?”

“Mother!” she said, and the events of the day came crowding back to her.

“You heard! Where is your mother? You know, do you not?”

She was too bewildered to deny her knowledge.

He said: “You know then, you know!”

She did not answer.

“By God,” he said, ‘so you are in this conspiracy against me, eh? Where has your mother gone?”

“I… I cannot say,” stammered Carolan.

“You cannot say! And why can you not say? Tell me that.”

She was silent.

“You have been sworn to secrecy, is that it?”

She nodded.

“It would be better if you told me now, you know.”

“I cannot tell.”

He looked down at her, livid with fury; not because Kitty had left him now, but because Carolan was in league with Kitty against him.

He gripped her by the shoulder and tore her nightgown. She was very small, he noticed, such a child.

“Look you here, Carrie, I will have no more disobedience in this house. You will tell me where your mother has gone, or I will whip you myself. Will you tell me ?”

But she knew she must not tell … not yet. They would not have gone far enough yet. She must wait a while, a whole day at least. Then he could never find them and bring them back. Mamma had married the squire because of her, Carolan; she had gathered that much; now it was her painful duty to save Mamma from the squire. So she pressed her lips tightly together and shook her head.

“You admit you know then?” he said, and she had known it, there was a pleading note in his voice: he wanted her to say she did not know; he wanted to put his great face close to hers and kiss her and say: “You are completely my daughter now, little Carrie.” But she knelt on her bed, her hands clasped behind her back, her face white and frightened, but her lips pressed firmly together. She was going to be silent for Kitty, and she would not speak to him.

“Very well,” he said cruelly, ‘we shall see whether you will speak or not. Margaret!” he roared, and Margaret, who had heard the commotion and had been awake for a long time, came in.

“Go to my bedroom, Margaret, and bring my riding crop. I will not have disobedience from my children.”

Margaret hesitated and wished she had pretended to be asleep. But he roared at her again: “Go! Or you will be the next. God Dammed, am I to be thwarted in my own house?” Margaret went, and he pushed Carolan on to the bed.

“Now, Carrie,” he said almost wheedlingly, ‘you tell your father what happened this afternoon. Where did she take you, eh? Eh, Carrie?”

Carolan said nothing. He bent down and gave her a stinging blow about her ear. He lifted her by her hair and pulled her up.

Her lips quivered.

“Are you coming to your senses, Carrie? Are you going to tell me?”

Carolan could only shake her head.

He threw her face downwards on to the bed and began to slap her body with his great hands. Carolan cried out, and he laughed.

“I will teach you, my girl!” he said.

“I will teach you!” Margaret came back and stood trembling on the threshold, the crop in her hand. He snatched it from her, and with it poised in his hand, stood staring down at the quivering body of the child.

“Dammit!” he cried.

“What do I want with this? I have strength enough in my hands to deal with the brat.” And he picked her up and shook her, and he saw that her eyes were tightly shut and that tears were squeezing themselves through her closed lids. Emotions mingled in his mind.

Then he saw Jennifer. She was looking in at the door, and her mouth was working. She had been at the gin bottle again, and she was laughing because he had beaten the child.

He picked up the crop and went towards her; she ran, her arms stretched out before her, into her room. He stood in the doorway, laughing at her. Then he looked over his shoulder at Carolan who lay still on the bed, her nightdress in ribbons about her bruised body, a sob shaking her now and then.

How loyal the child was! Loyal to that slut of a mother. And nothing for him but defiance.

“Carrie!” he said.

“I’ll see you in the morning. Then we will hear whether you persist in your folly or not.”

But he would not beat her again. He was the beaten one, not she. He had to get out or he would be petting her, telling her he did not mean that after all, and that whatever she had done mattered not, because he loved her.

He went to his bedroom, but not to sleep. And in the morning he sent for Mrs. West.

The child had to be whipped last night,” he said, and though he felt her disapproving eyes upon him; he did not resent that. He warmed to Mrs. West. He said, almost apologetically: “I was upset myself. Perhaps I laid it on a bit too strongly… But I will have no more disobedience in this house. Go to her. And take her something tasty to eat… And see that she is all right.”

In the evening of that day he sent for Carolan. She came to him, her head high, defiant.

By God, he thought, is she asking for another whipping? But how he admired her! She had something in her that Kitty had not had, nor perhaps Bess either.

“Well, Madam Carolan!” he said, with an attempt at lightness.

“Well?”

“Well what? Have I not told you to use some respect when addressing me? Did I not tell you to call me Father? You had better do so, unless you so like the feel of my hands about you that you are asking for more of what you had last night.”

She was frightened, he saw with satisfaction.

“You are not my father,” she told him boldly enough.

“So why should I call you such?”

“Look here, Carrie,” he said.

“I am your father. You had better tell me immediately who has said I am not.”

“My mother has said it. And I will tell you now what I would not tell you last night… She has gone away with my father.”

His face went white, then hideously purple.

“Ah!” he said at length.

“And Madam Carolan knew, and would not tell, eh?”

“No,” she said, “I would not tell.”

“For fear I should have gone after them?”

She nodded.

Brave little girl! Bold and defiant and disobedient. His eyes were filling with mawkish tears. Why was she not his daughter! He would have given anything to know she was.

“You need not have feared that, girl.”

“Oh!”

“And you might have saved yourself a whipping. Carrie, come here, girl. It did not please me to whip you like that. How do you feel?” He looked at his hands.

“They are big and clumsy, eh, Carrie?” He took her hand, and laughed comparing them.

She said: “I did not mind. It is all over now.”

Queer position. Am I asking pardon of Kitty’s bastard? It looked to him as if he were; he did not understand himself. Then,” he said, ‘we will forget last night, Carrie, eh? I was in a foul temper.”

“Of course,” she said.

“I know.” And she smiled, and when she smiled she was the image of Bessie … more Bessie than Kitty.

“And it does not hurt much now. Mrs. West was very kind.”

“Good for West!” he said.

“We will have a ride together tomorrow. Not West and II’ He roared with laughter at the thought, and put out a great hand and pinched Carolan’s cheek.

“These two, Carrie. Squire and his daughter, eh?” There was nothing sullen about her. She was adorable, this child. Kitty had left her; that made her solely his. After that Carolan’s life slipped on smoothly enough. She saw more of the squire; they rode together almost every day. He was eager to make up for that beating, and he tried to do so in lots of ways which on account of their very clumsiness were endearing. He was like a father to her; indulgent, though violent enough when crossed, and afterwards almost pathetically sorry for his violence. She avoided him when she possibly could, but when she could not she tried very hard to be fond of him, and after a time she began to find his companionship tolerable, even amusing.

Often she dreamed of joining her father and mother in London, because she was sure that that was what she was going to do one day. She waited for the promised letter which was to be enclosed in one for Mrs. West, and she was disappointed for weeks, but eventually it came.

She took it to her room and read it through many times. Her mother had given an address in London but she said it would not be possible for them to have Carolan with them just yet. They had their way to make and prospects at the moment were not very rosy; they would prefer their daughter to wait until they had a home to offer her which would be as luxurious as the one she would have to leave to come to them.

As if I care for luxury! thought Carolan, but she did realize that if she went to her parents in London, it would mean leaving Everard, and that most decidedly she did not want to do.

Carolan’s first ball dress was of green brocade trimmed with coffee-coloured lace. Its skirt was full and swept the floor; its bodice was rightly fitting and very dainty, falling from her shoulders, with tiny sleeves caught up with green ribbons. Her eyes matched the colour of her dress; and her hair, parted in the middle, hung in soft curls about her shoulders; it looked very natural and fashionable, unpowdered as it was, for powdering had gone out of fashion some four years before with the coming of the tax.

The squire had given her a dress; he had taken great pleasure in doing so. There was to be a ball, he whispered to her, and it was a great occasion Carolan’s first ball; she was to stop being a child when the old century ended and start her adult life with the new. The disreputable clothes in which she tore about the countryside were unsuitable for a young woman though they might do well enough for a child, so there must be a new dress and new slippers, and as the money for these was to come out of the squire’s purse, he hoped young Carrie was going to be suitably grateful. She was grateful; she gave him a kiss without being asked, which seemed to please him mightily.

Carolan, studying herself in her mirror, thought about the kiss she had given the squire. He still made her uneasy, as he had when she was a child. She could have liked him so much more but for his hearty caresses. He was kind to her. indeed more kind than he was to Margaret or Charles, which amazed her. He liked to ride with her, to take her round the estate, to make the cottagers curtsy to her. Queer man, but kind I Carolan bent her head and kissed her own white shoulder in an excess of excitement over this occasion of her first ball and the delight in herself dressed up in her first ball dress. Everard would be at the ball tonight. He had said: “Now, Carolan, I shall expect you to save plenty of dances for me!”

How beautiful was Everard! With his finely chiselled features and his courteous manners, he was aristocratic and gentle, elegant without being foppish; never really angry except on someone else’s behalf: never unkind. So calm he was, aloof, never excited by her as she was by him; she loved to sit on the wall between the Orlands’ house and the graveyard and listen to Everard’s talk of his future; and how he loved to talk! She twirled round ecstatically to glimpse at the back of her dress; she danced round the room and imagined she was dancing with Everard.

She came to an abrupt stop by falling against the old bureau in the corner; she was laughing at herself. Did everyone get ready too soon for their first ball?

She was so happy she had to dance. Indeed the last year had been the happiest of her life. In the bureau were letters from her mother; there were several which had come via Mrs. West over the last four years. Mamma was very happy in London; soon Carolan must join her and her father, but not yet; they were not quite ready … Ah, thought Carolan, let them enjoy their happiness without an intruder!

And she knew in her heart that she did not really want to join them; she was too happy here. It was true that the rough caresses of the squire sometimes perturbed her, and she understood him as little now as she had done when a child. But that was a small matter in the midst of such contentment, and Everard was the rock on which all this contentment was built. To go to London would mean to lose Everard; therefore she was glad when her mother wrote that they were not quite ready for her.

Life had changed for her. Everywhere it seemed good.

Charles, who was at Oxford now and home only occasionally, no longer tormented her. He scarcely seemed to notice her at all. Jennifer Jay had drunk too much gin one night last year, and had fallen from the top of a flight of stairs to the bottom; that was the end of Jennifer Jay. With Mrs. West and the servants she was a favourite, more so than Margaret, which surprised her, for Margaret was lovely to look at and the squire’s own daughter. But one of the deepest reasons for her contentment was Margaret’s sudden change of feeling towards Everard. Margaret had loved Everard a little while ago; now she was almost indifferent to him. If Carolan talked of him, she was scarcely interested, and that made Carolan very happy, because she knew Everard had never wanted Margaret to care for him so blatantly, and he seemed to like her better now that she was more or less indifferent towards him.

Margaret came into the room, looking delightful in her favourite blue, with her fair hair dressed high on her head.

“You look beautiful!” cried Carolan enthusiastically.

Margaret looked wistful, and said: “You always exaggerate.”

“How do I look?” asked Carolan, her head on one side pleadingly.

“All right.” said Margaret.

Carolan grimaced, and Margaret wondered why a dress, which had been merely pretty hanging in the cupboard, should, when draped about Carolan’s slender person, become provocative, seductive, all that in Margaret’s opinion a dress should not be.

Carolan quickly dismissed the disappointment which Margaret’s cool comment had aroused in her, and said: “Oughtn’t we to go down … since you will have to receive people, or something?”

“You need not come yet,” said Margaret.

“I must go.”

“Of course I shall come.” giggled Carolan.

“Do you know, I have been ready for at least half an hour, waiting! If I have to wait much longer I shall burst with impatience.”

“You are a silly child,” said Margaret, ‘and you say such silly things! I am going down now.”

Carolan followed her from the room. The squire from the hall below saw them descending the staircase, and stood there watching them.

By God, he thought, she is growing up. She is a woman. She is not much like Bess and Kitty smaller altogether, brighter, with more vitality. She has all they had though. Carolan … my daughter, Carolan!