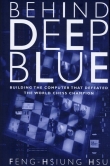

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“Carolan… Miss.” cried Jennifer in reproach. But Jennifer could say what she liked now. Mamma was soft and warm and smelt sweetly.

“So you are going to see Everard, darling?”

“Yes, Mamma. How nice you smell. You come too.”

“No, I cannot do that, but you shall tell me all about it when you come back.”

Carolan kept her arms round her mother’s neck, and laughed with pleasure. Over her daughter’s brown head with reddish tints in it, Kitty looked fearfully at Jennifer Jay.

Is she unkind to Carolan? wondered Kitty. It was not easy to know. Of course there had to be certain corporal punishment for all children, and especially for a high-spirited child such as Carolan who could at times be very naughty. But was she really unkind?

“Come, Miss!” said Jennifer.

“The carriage will be here at any moment.”

“Yes, Carolan, you must go.”

How I wish, thought Kitty, that I could get rid of that woman! She knew now that she ought to have got rid of her years ago, before Carolan was born before George had known that Carolan was going to be born. It would have been easy then. But now Jennifer was back in the position she had occupied when Amelia was alive; it amused George to give Jennifer a certain influence in this house. It was a way of humiliating Kitty as she. to the knowledge of the whole neighbourhood, had humiliated him.

When she was in the nursery Kitty was full of love for little Carolan. Such a lovely creature with her brown hair that glinted quite red in the sunshine, and whose wide green eyes were alert with interest in everything that went on around her. She had a heart-shaped face and a sweet mouth that was going to be rather like Kitty’s own; she had charm and appeal which Charles and Margaret, good-looking as they were, lacked. The years had left a certain mark on Kitty. She was modishly dressed almost showily; indeed there were those in the county and among them her Aunt Harriet who thought her fast, flamboyant a characteristic which displayed itself in her clothes. But the squire liked to see her thus, so there was a handsome enough dress allowance. She had a French maid, Therese, and a little black boy, Sambo, whom she petted. She spent a good deal of time before her mirror, while Therese tried new hair styles and discussed clothes. Once George, coming into her room suddenly and seeing her before her mirror with Therese combing her hair and the black boy sitting at her feet eating sweetmeats, had said: “You were born a harlot, Kitty.” and he dismissed Therese and the boy and made love to her there and then. She was so angry that she fought him, and he seemed to like that; but now she was indifferent to his humiliations. He did things like that, getting great satisfaction from them. Openly he lived with Jennifer. He was the same squire who had always been chasing the prettiest village girls, for he had lost his dreams of becoming the perfect squire, and when he remembered them he blamed Kitty and tried to hurt her. She was impregnable. At first she had had Carolan, and Carolan had been all-sufficing; how she had loved the little girl with the dainty hands and feet and the wide wondering eyes! She had bathed her and powdered her, and lived for her. But motherhood could only be a secondary emotion with Kitty, and there were lovers. First there was the young son of a neighbouring squire, who had reminded her of Darrell because he was so gentle and grateful. Later there were others. Therese was an adept at intrigue; she made the deception of the squire an adventure which was always on the point of being discovered, but never was. So Kitty loved Carolan when she was in the nursery, but when she was not there she forgot her for hours at a time.

Carolan did not know this. She adored her mother; she thought that she longed as deeply as Carolan for them to be together always, to go away somewhere, right away from Haredon, where they would live alone and never see Charles and Jennifer and the squire; though sometimes Margaret should come to see them and bring some of the servants those whom Carolan liked best.

Carolan usually lost herself in this dream when she and her mother were together, even in the nursery with others around them. Perhaps, she thought now, Charles and Jennifer should come and she would say all the things she had wanted so many times to say to them; she would tell Jennifer that she was ugly, and Charles that he was silly. And they would not be able to do anything about it, because the cottage in which she lived with her mother would be a magic place and she only had to snap her fingers and two great dogs, breathing fire, would spring from nowhere and drive Jennifer and Charles away. Such a lovely cottage it was, with fruit trees all round it; and in the cottage it was always daytime. Only on very rare occasions should the squire come there, because she was frightened of the squire in much the same way as she was frightened of the dark. This fear was inexplicable, because she did not always want to run away from it. It called her to it, even as it terrified her. She always thought of George Haredon as the squire, because both her mother and Jennifer referred to him by that name when they spoke of bun to her. He was a colossus of a man; he wore the biggest riding-boots in the world, and his hands were not like human hands; they were covered in black hair like the hair he had on his face. And his black eyes had a lot of red in them which she could not stop looking at. Sometimes he would lift her on to his knee and caress her as though he loved her; he would stroke her hair. He had a hoarse voice; often he said: “By God, Carrie, you’re going to be such another as your mother.” His face would look very ugly when he said that, and he would put it so near hers that she could see each thick black hair of his eyebrows, and the red in his eyes formed itself into shapes like rivers on a map. Then he would say: “And if you are, girl, I’ll break every bone in your body before I’ve finished with you!” which sounded very frightening coming from him, but was not meant to be perhaps, because he laughed when he said it. And sometimes he would kiss her in the hollow of her neck which Jennifer said was like a salt cellar, she being so thin and ugly, and sometimes he would put his great mouth on her eye so that she had to shut it quickly. A terrifying person, the squire. She hated the smell of him. Once she had wrinkled her nose, and he had said: “What does that mean?” And she had answered: “You have a horrid smell.” And because she thought that might be very rude, she added: “The Squire!” She had called him that once or twice, as though it were his name, and it had amused him. But it did not amuse him then; he put her from him in a tantrum and strode away, and she hid herself thinking that if he found her he really would break every bone in her body. And next time he picked her up and set her on his knee, she made a great effort not to show that she did not like his smell. But for all this he fascinated her, and sometimes she would deliberately get in his way just to see whether he would be angry with her or caress her; and either was equally terrifying to her. Aunt Harriet should come to see them at the cottage too, and she, Carolan, would call up the dogs that breathed fire, very quickly if Aunt Harriet was unpleasant, for Aunt Harriet could be very unpleasant. She had hard hands that hurt when she slapped, but Carolan did not mind that so much; it was Aunt Harriet’s cold eyes and grim mouth that Carolan hated. They seemed to be holding a secret a horrible secret about Carolan.

But the dream of the cottage and its visitors and fire-breathing dogs was over, for Kitty was gently disengaging her hands and Jennifer was gripping her shoulder.

“It is time the children went now, Ma’am.” Jennifer released Carolan, and going over to the mirror put on her bonnet.

Kitty thought how desolate Carolan looked, standing there. So much smaller than the others … And was Jennifer kind? Margaret took Carolan’s hand and pulled her to the door. It was pleasant to think of the older girl’s keeping an eye on little Carolan, and Kitty had always liked Margaret. Now Carolan was looking over her shoulder at her mother, and her face puckered a little; she looked such a baby, scarcely her five years now, though one was apt to think her older at times; she was such an old-fashioned little thing. Kitty wondered whether she would give up her afternoon to the child, keep her with her. But no! She had an engagement. Besides, children were moody; you were apt to think them unhappy when they were just a little peevish. And, in any case, all the children had been invited to the rectory; it would seem rude if one of them stayed behind. So Kitty eased her conscience; if Jennifer was unkind to her, surely Carolan would say so. She watched Their getting into the carriage, and told herself how good it was to know that Carolan was being brought up with other children. Jennifer would not be different from what she was to the others; she would not dare.

The carriage rattled over the stony roads. Carolan began to bounce up and down on the seat for the sheer joy of riding along country roads in a carriage. Jennifer slapped her.

“Still. Miss.”

She was going to be the image of her mother, thought Jennifer; not so beautiful perhaps she would be darker for one thing and her eyes were green but those thick red-tinted lashes and that provocative tilt of the head, She had… what her mother had, and if one could believe the stories one heard, what her grandmother and great-grandmother had had too. Jennifer wanted to beat that small wriggling body, but what was the good. There would be trouble if she went too far in that direction; the artful little imp already had some sort of influence with the squire; Jennifer believed he was more interested in Carolan than in his own children. Sometimes he could not keep his mouth from smiling when he spoke of her. What witchery was this she had inherited, when at five years old she, the very sight of whom should have enraged the squire, could command a special indulgence?

“Now you must all be very good at the rectory,” said Jennifer.

“You must not let your crumbs fall upon the floor. And when Mr. or Mrs. Orland speaks to you, you must answer up promptly and very respectfully. And if Everard should take you into the graveyard, you must be very quiet.” She gripped Carolan’s arm, for the child who had been staring out of the window before she had mentioned the graveyard, was now sitting up tense in her seat.

“Don’t go prying around too much in the graveyard.”

Margaret, who was very matter-of-fact and without much imagination, said: “Why mustn’t you pry round the graveyard? I can’t see that it matters; everybody there is dead.”

“Hush!” said Jennifer, and looked at Carolan.

“The vaults are interesting,” said Charles.

“Full of dead people!”

They put the coffins on shelves,” added Margaret.

“So that one family can keep together,” said Jennifer.

“I’ve heard stories about what happens in the graveyard at night; it would make your flesh creep to hear them!”

“They are like little houses,” said Charles.

“Houses where the dead lie,” said Jennifer.

“Now, Carolan. there is no need to look so frightened, Miss. Nobody is going to put you there. But mind you don’t go prowling round where you should not go, and get shut in with the dead. A nice thing that would be!”

Carolan was white to the lips at the thought of it.

“Baby!” said Margaret contemptuously.

Carolan shut her eyes and tried to tell herself that she was not in the carriage at all, but in the cottage with Mamma.

“Sparks!” she murmured to herself.

“Rover!” For those were the names of the dogs which breathed fire.

The carriage had drawn up outside the rectory gates, and Mrs. Orland and Everard came out to greet them. Mrs. Orland was very gracious. She was sure, she said, that Jennifer would like a chat with her friend, Mrs. Privett. Mrs. Privett was the housekeeper at the rectory, and Jennifer hated her. This was one of the humiliations which made her so angry. She might have been riding in her own carriage to pay a call, had her plans not gone wrong; now she was here in The role of governess, and Mrs. Orland’s drawing-room was closed to her; she must go to the housekeeper’s room and chat with that stupid Mrs. Privett whose talk was all of apple jelly and inferior servants.

“Well,” said Mrs. Orland, ‘and how is little Carolan?” Carolan was quite the most charming of the Haredon children, even though she had made such a distressing entry into the world. Mrs. Orland was afraid she was a little too broad-minded, but one could not help liking the child.

Carolan put her hand in Mrs. Orland’s and they went into the drawing-room.

Everard looked very handsome today, and bigger than Carolan had been thinking him. He sat down, and his feet looked just like a man’s feet; Carolan’s did not reach the floor, and she longed for her legs to grow so that they would. Margaret sat staring at Everard; she was always like that in Everard’s company; she doted on him, and he did not like it very much. Margaret knew it, but she could not help staring at him. Carolan stared a little at him too, but there were other things to stare at in Mrs. Orland’s drawing-room, because it was such a wonderful place, and Mamma’s mamma had lived here once, when she was Carolan’s age, which made it a very exciting place to be in.

Mrs. Orland talked to them very brightly while they ate seedcake and drank their milk. She talked of lessons, but that was not to Carolan who was too young to know much about them, but to Charles chiefly, occasionally bringing in Margaret. Carolan did not mind being ignored; she was quite happy; she loved seedcake and the milk was delicious, and on a stand near her chair was a fascinating ornament which represented a woodland scene; it was set on a wooden stand, and there was a glass shade over it. It was wonderful. There was green moss and some trees, and on one of the branches a real stuffed bird. When she pressed her face close to the grass she could imagine she was standing under the trees, and that her cottage was not far away, and that her dogs would come leaping out at her from behind those trees. Mrs. Orland was saying: “Would you like me to take off the glass shade?”

Carolan had no words to express her delight. One plump finger stroked the bird’s feathers.

“Pretty, pretty pretty!” cooed Carolan.

Such a baby, thought Mrs. Orland, although sometimes she had the air of quite a sophisticated young person!

Margaret was standing near Everard, saying shyly: “Everard, please show me your books; I do want to see your books!”

Everard almost scowled, but Mrs. Orland said: “Take Margaret to your study and show her your books, Everard.”

Everard said: “I do not want to Mother. I…”

“Everard. Margaret is your guest!”

Everard went very red, and led Margaret ungraciously towards the door.

“And when you have seen them, you may join the others in the garden. And remember … not too much noise. Papa is writing his sermon.”

Carolan said: “Is he always writing sermons?”

But no one answered that, and she supposed he was, because whenever she was at the rectory she was always told to be quiet on that account, and she could not imagine the rectory unless she herself was there.

“Now, Charles, suppose you take your little sister into the garden and show her the nice flowers until the others come down. You would like to see the nice flowers. Carolan?”

Carolan would have liked to stay with the wood on the stand, but Charles was eager to escape from the restraint of Mrs. Orland’s drawing-room.

“Come on, Carolan!” he cried, just as though he really wanted to show her the flowers, so that Carolan thought he had changed suddenly, and liked her after all.

It was lovely in the garden.

“Who wants to see her old flowers!” said Charles, but he said it in quite a friendly way, and Carolan laughed because she had always really wanted to be friendly with Charles.

“Do you want to see her old flowers, Carolan?”

“No,” said Carolan.

“Nor do II’ He laughed as though it were a great joke and Carolan laughed too because she was never sure about jokes, and always laughed when she thought there was one.

Charles led the way to the end of the garden, and at the end of the garden was a low stone wall__and beyond the wall was the graveyard.

“They look funny, those gravestones!” said Charles, and he laughed; so, thinking it was another joke, Carolan laughed too.

Charles was being very nice this afternoon.

“See me leap that wall!” he cried, and did so.

“You could not do it!” he challenged.

She knew she could not, but she tried. He stood on the other side of the wall, laughing at her, but not in a spiteful way.

“You are too little, Carolan; you will be able to when you are bigger.”

“I wish I was bigger!”

“Oh… you will be one day. Give me your hand and I will help you over.”

She scraped her knees getting over, but it was exciting being on the other side of the wall. She liked it. The gravestones were like ladies in grey cloaks, but they did not frighten her; the sunlight glinted on them, making them sparkle, showing her that though they might look like people they were only stones after all. How she loved the great blazing sun up there. It was such a comforter; she was not afraid of very much when she felt that to be close by.

“See if you can catch me,” said Charles, and he walked quickly amongst the gravestones.

“I walk!” he called over his shoulder.

“You run. That is what you call handicaps, Carolan. Oh …” For she had nearly caught him. Carolan shrieked with delight; she forgot all the unkind Charleses she had known, and remembered only the kind one who had helped her scramble over the wall and let her play touch with him in the graveyard. She caught him and they stopped, laughing, by the side of what to Carolan looked like a little house covered in ivy.

“Do you like it?” asked Charles. She shook her head.

“It is like a little house,” she said, ‘but it has no windows. I like windows.”

“Do you know what it is ?”

“No.”

“It is what we were talking about… you know… a vault… It is our family who live in there our dead grandpapas and grandmammas and uncles and aunts …”

“Oh!” said Carolan.

“Walk, and I will catch you.”

“Later on perhaps,” said Charles.

“Now I am going to look in there.”

“But you must not.”

“I can if I want to, and I do want to.”

He tried the door, but it was locked, and she was filled with relief.

“You cannot,” she said gleefully.

“Carolan, you would be afraid.”

She stoutly denied it. She could do so happily, for how was it possible to go through a locked door?

He said: “Carolan, if that door were open, would you go in? I would, I would want to go in.”

“So would II’ He put his hand in his pocket and brought out a key. She stared at it in dismay and horror.

“But Charles … How can you have a key… for that?”

He took her hand; he held it lightly just as though they were friends. Then he opened the door; there was a short flight of steps that led down into darkness.

He looked at her over his shoulder.

“Papa keeps the key,” he said.

“I have seen it often in a drawer in the library with other keys. I took it because I wanted to see what it was like in here. You do too, Carolan. You said so!”

She was silent. It was a different world in there; it was damp and it was dark and there was none of her well-loved sunshine to defy the darkness.

“Come on.” said Charles. He was excited; he had meant to enjoy this adventure with Everard, so he had taken the key and hidden it in his pocket. He was almost sure once that Jennifer had felt it there, but she had said nothing so she could not have noticed it; and then her words in the carriage had made him see the possibility of another adventure with Carolan instead of Everard whose years made him inclined to be superior.

He took Carolan’s hand, and she descended the stairs with him reluctantly.

“What an odd, nasty smell!” she said, and her teeth began to chatter.

“Earth and worms and dead people!” said Charles. That is what you smell.” His voice was shrill with excitement. Now Carolan’s eyes had grown accustomed to the darkness; they were standing in what was like a room, very cool and quiet, she thought.

“On the ledges,” said Charles with his mouth close to her ear, ‘are the coffins. Oh, does it make your flesh creep, Carolan?”

“No!” lied Carolan.

“But I like outside best.”

“But you wanted to come, Carolan. You said you did.”

“Yes, but we have been. I can catch you; you cannot walk faster than I can run.”

“Would you be scared to stay down here all night. Carolan?”

“I would not stay here all night.”

“But if you did …?”

Her show of courage deserted her; she made for the steps.

“Listen!” said Charles.

“What was that?”

She stood still; she could hear nothing but the wild beating of her own heart and Charles’s breathing. He caught her shoulder suddenly; he gave her a little push backwards; her fingers touched the clammy wall. She shrieked, and then horror silenced her, for Charles had leaped up those steps and had shut the door on her. She scrambled up the steps as fast as she could, but the door was already closed. Now there was no comforting light at all… nothing but the damp darkness. She beat her fists on the door.

“Let me out! Let me out! Please … please let me out!” There was no answer. She went on beating her little hands against the heavy door. She found the lock. She pushed, she kicked. But Charles had locked the door; he had taken away the key.

Carolan shut her eyes tightly and pressed her face against the door; she felt that a thousand horrors were rushing up the steps after her; she waited for something terrible to happen. She went on waiting. Nothing happened but the awful stillness pressed in en her, and the cold damp darkness was more unendurable than anything else could have been.

She could not keep her eyes closed for ever; she must open them. Fearfully she looked over her shoulder. She could just make out the dark entrance to the room; she turned and pressed her back against the door, her eyes fixed on the entrance to that room. Whatever was coming for her would come from that direction, she knew. She remembered the stories she had heard whispered by the servants; Jennifer had told her some horrible stories about dead people. Would they be angry with her for venturing into their home? She had lied; she had said she was unafraid, believing she would not be called upon to prove her lack of fear. Jennifer said liars went to hell; but what was hell, compared with this dark home of the dead?

“Charles!” she screamed; but the sound of her own voice, echoing about her. frightened her so much that she pressed her lips together lest any sound escaped to terrify her.

She did not know what to do. A sob shook her. She began wildly kicking the door again, but the hollow sound of her kicks echoed through the place as her voice had done.

“Mammal Mammal’ The words must escape. She shut her eyes and began to pray.

“I did not want to come here. I took only one small piece of sugar yesterday. It was not I who put my finger in the apple jelly. I did not. I did not! If I could get out of here. I would never do anything wrong again. I would never make faces at anyone… not even Jennifer…”

What was that? Only some small animal scuttling along down there in the gloom. She started to shiver, and her face was wet, but not with tears, for strangely she had shed no tears. Tears were soft and comforting things, and there was no comfort for her in this dark place.

Would they come out of their coffins? What would they look like? She shut her eyes tightly. I will not look at them… I will not look. Perhaps they would force her to open her eyes, and they would be horrible … horrible and angry with her for coming into their house.

“Oh, let me out. let me out!” she sobbed.

She found she was lying on the damp ground, her head pressed against the door, her hands over her ears, great sobs shaking her. Something must happen soon. Now she lifted her hands; she must hear. She was sure strange noises were going on all about her. Was it better to hear or not to hear? To see or not to see?

A ghostly voice whispered: “Carolan!”

She trembled.

“Carolan!” said the voice again. She stared at the entrance to the room which was the home of the dead, and she heard the voice again: “Carolan! Carolan! Are you there. Carolan?”

It was Everard’s voice, coming through the door, and she was almost fainting with the joy of hearing Everard’s voice; but she could not speak though her lips were moving. Frantically she tried to find her voice; he would go away: and he would leave her. He was there, but she had lost her voice and could not call to him.

“Carolan! Carolan. Are you there, Carolan?” She tried to get to her feet, but she was shaking so much she could not stand.

“Please…” she managed to utter, but her teeth chattered, and the words could not come out.

She tried again and again, and then she heard Everard’s footsteps going away.

Despair seized her. She could shriek now.

“Everard! Everard! I am here. Oh, please get me out, Everard!”

But she was too late, for he had gone, and she would have to stay here all the night. The night? But here in this dark place it was always night. There was the faintest gleam of comfort in the thought, and it gave her the courage to raise herself and to turn her gaze on the dark entrance to the room.

It began again now the staring about, the closing of her eyes; one moment alert, the next shutting out all sound and all sight.

Every movement about her set her heart pounding afresh. Sometimes it was the rustle of the trees outside; sometimes it was the call of a bird.

“Everard, come back.” she prayed.

“I can talk now … I can talk.” And she went on talking, just to assure herself that her voice was still hers to command.

Surely Everard would come back! Why had he said her name if he had not thought she might be there?

“Carolan!” A key turned in the lock, and Everard almost fell over her, lying there. He picked her up. She stared at him, still terrified, wondering if one of the dead ones had come for her and, as an additional torture, had made himself look like Everard. Everard sat down on the top step, just as though it was anybody’s step, and held her in his arms. She thought he looked frightened, but she only seemed to see things through a haze.

He said: “Everything is all right now, Carolan. I am taking you out of here.”

She was shaking so much she could not answer him. He was very tender, Jennifer said he was a mollycoddle. He did not play games; he liked his books; one day he would be a parson like his father, and write sermons all day long. But one thing Carolan knew instinctively about Everard; he would never lock frightened little girls in with the dead; and to Carolan, newly released from hell, he was wonderful.

He went on talking while she lay in his arms, which was just what she wanted him to do.

“There is nothing to be afraid of, Carolan. The dead cannot hurt anyone; besides, they are your own dead here. They would love you if they were alive, just as people at home love you.”

Just as people at home loved her? Charles? Jennifer? The squire? But did it matter what Everard said! She only wanted his protecting arms round her and to listen to his soothing voice.

“There!” said Everard softly, like somebody’s mother. There! You feel better now.”

Then her tears began to fall, and she could not stop them.

“Oh, I say!” cried Everard in real dismay.

“Oh, I say, you know, it is all right now, you know.”

But she could not stop the tears, and to show him that they were not really sad tears she began to laugh, and she was laughing and crying all at once, which frightened Everard. He kept saving her name.

“Carolan! Carolan!” and rocking her to and fro as though she were a baby. And eventually she stopped laughing and was only crying. Then Everard said: “I hope I have hurt him badly, I do!” She was so interested that she stopped crying and asked: “Who, Everard?”

“Charles!” said Everard.

“Let us get away from this place. We ought not to have stopped here; it is a dismal hole.”

They went out and he locked the door after him. She stared round-eyed at the key.

He said: “Your eyes are red!” And she began to sniff again. Then he added: “I don’t mind admitting I should not have liked being shut in there alone myself… much.”

And saying that was almost as wonderful as letting her out. He was twelve years old and she was five, and yet she felt a wonderful companionship spring up between them.

She could see the sunshine glinting through the trees, and she stared up at it, at the lovely sun itself. And when she blinked and shut her eyes she saw red suns on her lids, as though it were saying to her: “It is all right. It is all right. You see I am here, even when you shut your eyes!” And she was suddenly wonderfully happy; she leaped up and kissed Everard. He did not much like being kissed by a little girl of five, but he was faintly aware of the charm of Carolan, of green eyes shining between swollen lids and a sweet and tremulous baby mouth.

“I say.” he said.

“I say!” and wiped off Carolan’s kiss, smiling at her as he did so to show that he was not as annoyed as he might easily have been.

“You should bathe your eyes,” he said.

“I will take you to the pump in the yard, shall I?”

She nodded. Willingly she would have followed Everard to the end of the world.

Just as, a little while ago, everything had been dark tragedy, now everything was very gay or extremely comic. She laughed when Everard pumped the water and gave her a lace-edged handkerchief, which she held under the water. Then he stopped pumping, and said: “Here! Give it to me.” And he took it and bathed her face with it, and again she thought he was like somebody’s mother.

“Everard,” she asked him, ‘how did you get the key?”

“I knew he had it,” he told her, and that was another delightful characteristic of Everard’s; he did not say, as the others would: “Oh, shut up, baby.” or “You wouldn’t understand.” Everard went on: “He showed it to me this afternoon. Then, when I saw him without you and asked where you were, he looked sly and I guessed: so I came and called you, and when you did not answer I was afraid you had fainted.”