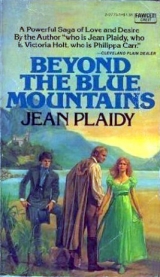

Текст книги "Beyond The Blue Mountains"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

His eyes went to Margaret. Nice enough just the wife for young Orland. Margaret’s place was in a country parsonage. Amelia’s girl! And, by God, no one could have any doubt of that. And tonight that young milksop would come to the point, he hoped. The young fellow was a plaguey long time deciding that he wanted to take the girl to bed with him. Still, there was nothing like a ball to bring a young man to the point; show him Margaret’s people knew how to entertain, by God! Show him what sort of a family he would be marrying into. She was nigh on twenty! Time she was off his hands. How the children grew up! Carolan next. No, not Carolan she was his girl, his little daughter. This last year he had been happier than he had been for a long time. He was beginning to shape into that pattern he had cut for himself. He scarcely ever flew into one of the wild rages that had come to him so frequently at one time. People might think he was getting old, but it was not that entirely; he was not getting old; he was getting what he wanted. He had his little Carolan. Why did not Margaret’s eyes sparkle as Carolan’s did? Why did not her hair glow with that vitality?

His hand came down on Carolan’s shoulder.

“By God!” he cried.

“What have we here? I thought it was a child, but it is a young woman!”

She glanced at him through those thick lashes.

“Children are not given ball dresses, are they?” she said.

“Pampered ones might get all sorts of things out of their old fathers.”

She was scintillating. And this at sixteen! He was faintly worried, seeing her like this. He wanted her to remain a child.

“Well, sir,” said Carolan, curtsying, ‘this child is a child no longer.”

He touched her nose with a clumsy forefinger, made her take one arm, offered Margaret his other. Now he was proud and happy, standing with Margaret Carolan in the background -receiving the guests. He was the good squire now; he had been wild in his day, but what young man is not wild in his day? His cottagers could bring their troubles to him nowadays; he might roar at them; he might lose his temper now and then; but he did what he could for them; he was a good squire.

A girl in the uniform of a parlourmaid flitted through a door and across the room. His eyes followed her. That was Emm; and he glowed again with satisfaction. He was not a bad squire really … large hearted and tolerant. Good squire, people would say when he rode by with his daughter. Wild in his day, but a fine master! So many men would not have had Emm in their houses after Harriet had turned her out. Emm! He could laugh at the thought of one starry night when she had run from him and locked the door on him. She had saved her virtue for a young labourer who had promised her marriage and then deserted her. So virtuous little Emm had found herself with child and nowhere to cum. But the squire was a good squire, and Emm would never cease to bless him to the end of her days. He had not said: “Now you see what it is to trust a labourer; better far to trust a squire!” He had never deserted a woman. If there was a child he had seen that it was put out somewhere and a lump sum paid for it. Poor little Emm! What would have happened to her if she had lived in a neighbourhood where the squire was just a squire! But Emm had her baby at the cottage of Jane Lever the midwife, and a man and his wife who had no children looked after it; and Emm came to Haredon to be parlourmaid under Mrs. West. And she was shapely, a personable enough young woman; and she was grateful to the squire: but not once had he looked in her direction. That was the man he had become. He was bowing over Mrs. Orland’s hand, well pleased with himself and with life. Carolan watched the guests arrive. How lovely the old hall looked, decked out like this, the beautiful dresses of the women, the elegant garments of the men a blaze of colour and lights and beauty! And here was Everard, more elegant, more beautiful than any.

He stood before her, his eyes shining.

“Why, Carolan, you have grown up overnight!”

“That is what everyone is saying. You like the change, Everard?”

“I like it very much.”

She smiled her pleasure.

“The dress is beautiful, is it not?”

“Very beautiful.”

“It cost a good deal, but the squire insisted on my having something really good for my first ball.”

Mrs. Orland came swiftly to them.

“Hello, Carolan! It is going to be a wonderful evening, I am sure. Now Everard, the squire was going to open the ball with Margaret, but he feels unable to and he wants you to do it for him, Everard. Look, dear, do go over to Margaret right away. It is time to start, and the musicians are waiting. I will look after Carolan.”

Everard smiled over his shoulder at Carolan. He was docile always.

“And, Carolan,” said Mrs. Orland, ‘here is Geoffrey Langley coming over. I know he wants to dance with you. Ah … Geoffrey, my dear boy, you have come to ask Carolan to dance, have you not?”

Geoffrey Langley, rather portly, middle-aged and bucolic, said he had been coming over to them with just that idea.

“There!” said Mrs. Orland, with the air of one who had worked very satisfactorily on behalf of others.

“You will look after our little Carolan, Geoffrey: this is the dear child’s first ball!”

Geoffrey Langley’s small eyes smiled appreciatively as he held out his hand.

Now Margaret and Everard were dancing together down the centre of the hall, and other couples were falling in behind them and the fun was beginning.

Geoffrey Langley was not sorry to relinquish his partner to another. She was an enchanting child but her feet had wings, and his ageing body could not keep up with her frolicking. Her next partner was a young man who told her she was beautiful, and tried to urge her out into the grounds because he was sure there was a wonderful moon. But Carolan wished to stay in the ballroom until Everard came to dance with her; but she was enjoying herself, waiting for Everard. It was fun to note the effect she had on this very young man, particularly when she remembered that last week, riding with him at the hunt, he had not given her a second glance. Oh, what a difference a ball dress can make! So she was coquetting, flirting in as natural a manner as her mother had before her. People glancing her way, noting her brilliant green eyes, her flushed, enchanting little face, thought, There will be trouble there! What is it those women have? The squire must watch out.

But there was in Carolan something neither her mother nor her grandmother had possessed, something more spiritual, less voluptuous; pleasure loving, certainly but something finer too.

The evening was wearing on when Everard found her. There was a faint colour under his skin, and he looked as exasperated as it would be possible for Everard to look.

“Oh, Everard!” she said.

“How nice to see you! I hoped you would come to dance with me before the evening was over.”

There was the faintest reproach in her voice. This evening had taught her that she was not the child, Carolan, waiting to be noticed by grownups; she was a woman, to be sought after. That she had learned, and it was intoxicating knowledge.

Everard said: “I have been trying to get to you the whole evening. There were so many things I had to do. My mother said that, since this is Margaret’s dance and the squire suggested I should open it with her in his place, I must dance quite a number of dances with Margaret. And,” he added severely, ‘when I did come to you, you were very busily engaged elsewhere.”

The flattery of this to one who, such a short time ago, was but a child in a nursery, bullied by Charles, tormented by Jennifer, whipped and made to realize that she was of no importance whatever, was intoxicating.

“Well,” she said, ‘could I sit waiting for you all the evening?”

“No,” said Everard.

“Let us dance.”

They danced, and all arrogance dropped from her shoulders then; she adored Everard, and this was the great moment of her evening.

“How pretty you are, Carolan! I did not know how pretty until tonight.”

Little waves of pleasure ran all over her. She tossed her head.

“Then it is my gown you find so pretty!” she challenged.

“Your gown! My dear Carolan, I have not looked at it.”

“Ah.” she cried.

“Shut your eyes, Everard, and tell me what ” it is.”

He closed his eyes; she looked up at him. Oh, he was wonderful beautiful and wonderful! And she had never been as happy in her life as now.

“Blue,” he said.

“You are thinking of Margaret!” she told him.

“No,” he said, with a seriousness that made her heart beat very fast.

“I am thinking of no one but you. Carolan, when I saw you flirting so outrageously with that young man…”

“Everard! I… flirting!”

“Exactly!” said Everard.

“Flirting! Inviting compliments -perhaps demanding them! Oh, Carolan, what has happened to you? You are different tonight.”

“I am a young woman at her first ball, Everard. Yesterday I was a child in a nursery.”

“Carolan, you alarm me. You are being a little silly tonight.

Carolan.”

“Let me be silly, Everard. I am so happy! I have never had a ball dress before. I have never before been to a ball. Is not a little silliness pardonable?”

“Perhaps,” said Everard, ‘but it grieves me.”

“Then I will be silly no longer, because I hate to grieve you, Everard.”

“Carolan… you say such things!”

“Everard, you too are different tonight.”

“No,” he said, “I am not or if I am it is entirely due to the difference in you. I have been very, very fond of you for a long time.”

“And I of you, Everard.”

“You are not very old, Carolan.”

“You forget… I grew up overnight!”

“Ah! How I wish you had!”

“But you said you were fond of me as I was.”

“Carolan, there are times when you frighten me. You are so impulsive.”

“And you, Everard, are far from impulsive; that is why you do not like that in me.”

“Who said I did not like it? Perhaps it is that I like. Carolan, I had not meant to speak to you tonight__but I am going to, because I must. I am afraid, Carolan.”

“Afraid? Of what?” She looked over her shoulder as though she expected to see something fearful there.

He laughed.

“You baby!” he said.

“I do not like being called a baby,” she said with dignity.

“But you are one. And such I will call you if I wish to.”

“Everard, you look most unlike yourself.”

“I have learned something, Carolan. I cannot talk about it in here; let us go outside. Let us go to the summerhouse; there we can be alone and talk. Will you come?”

Would she come? She would have followed him to the end of the earth if he asked.

Daintily she picked her way across the grass, lifting the green brocade, feeling not Carolan the child, but a lady who found life intriguing and full of adventure.

Everard shut the door of the summerhouse, and when he spoke his gentle voice was hoarse.

“Carolan, I told you that, seeing you tonight, I was afraid.”

“Yes,” she said.

“Carolan, dear little Carolan, do you remember when Charles locked you in the vault?”

“Yes, Everard.”

“And I came and found you there, and you lay across my knees and were so frightened? Oh, Carolan, that was when it began… That was when I began to love you.”

“Did you, Everard?”

“Yes. Just as a child then, as a little sister. You were so frightened and I was angry, more angry than I had ever been in my life.”

“You gave him a black eye, and he had such difficulty in explaining!”

He caught her hands, and they laughed.

“What do you feel for me, Carolan?” he asked.

“Would I not love the person who rescued me from that horror?”

“But love is more than that…”

“But that was the beginning. I loved and loved and loved you, Everard. You did not show any sign of loving me.”

“Did I not?” he asked in surprise, and she laughed with pleasure, thinking of those days; and it was all part of the pleasure of this evening that Margaret had ceased to love him.

“Not a bit!” she said, and laughing, moving nearer to him, she murmured: “And do you now, Everard ? I am not so sure.”

It was invitation, and Everard took it; he put his arms about her. He would have kissed her gently on the mouth, but there was no gentleness in Carolan. Everard was a little shocked, and because it was exciting to be shocked, he was enchanted with her. He had meant to explain, as one would to a child, that he loved her, that one day he would marry her perhaps in one year, perhaps in two; he had meant to be gentle; but it was Carolan who was leading the way and she sixteen, while he had lived twenty-four years. Carolan was no child; she was a woman because she had been born a woman.

She said: “For so long I have wanted you to kiss me, darling!”

And he drew back, still shocked, but mightily intrigued. This was so different from what he had imagined; he had rehearsed little speeches … “Do not be frightened, Carolan. You are too young to understand … You will be safe with me. I will wait until you are ready …” And she put her lips to his, and there was a quiver of passion in her as she said: “For so long I have wanted you to kiss me!”

He said rather hesitantly: “Carolan, let us sit down.” They sat, and he put his arms about her; she caught his fingers and held them fast against her breast. He thought, she is so innocent, this little Carolan I And he made up his mind to marry her soon and look after her. Wayward she might be, as her mother evidently was, but she was sweet and impulsive and loving and passionate, She needed a curbing hand; and it should be his gentle hand “You know I shall be leaving here soon, Carolan. I shall have a ( living and … and … I shall want you to come with me as my wife.”

Through half-closed eyes she saw the moonlit garden, the outline of trees and hedges. There was a scent of lime trees in the summerhouse, and this was the happiest moment of her life.

“Everard,” she said, I will come. Any time you wish, I will come. I will come tomorrow.”

He laughed gently and put his lips to her mouth, because he longed to feel the eagerness rising in her. It delighted him, alarmed him a little.

“My darling,” he said, “I shall not ask you to come tomorrow. These things need a good deal of arranging, you know.”

She lay back in the seat, and he saw her wide eyes, her parted lips.

“Ah, but I meant if you wanted me to come tomorrow, I would.”

“My sweet Carolan! But think, there is your family and mine!”

“But, Everard, what do we care for them? It is you and I… is it not?”

She was like a wild bird, he thought. She was enchanting; she was delightful. He wanted to fall on her and kiss her, and blot out the rest of the world as surely she was inviting him to. He remembered his sober years. I am a man; she is but a child, for all her exciting ways, her ball dress and her passionate love. The exciting things were so often forbidden, were they not? The things that appealed to the senses must be eschewed. Oh, yes, that was what he had always thought. In the days of his boyhood he had thought of entering a monastery; suffering hardship for his faith; he used to think up forms of self-torment as other boys invent new games. In those days he had told himself he would never marry, and he had meant it too, until Carolan came, with that particular quality in her which turned his thoughts from his religion to sensual love. He had compromised then; a priest may take a wife, may he not? He was no Catholic no monk! He shivered to think of the predicament he might have been in, had his mother granted his wish to enter a monastery.

And now Carolan was beside him. Carolan! Carolan! A man. even a man who is a parson, may enjoy his wife.

“Everard,” she said, clasping her hands, “I shall be such a good wife to you. I shall have my work to do, shall I not? There are special duties of the parson’s wife. Do you think I will suit, Everard?”

He gripped her shoulders hard, trying to fight the excitement that was coming on him again.

“You will suit Everard perfectly,” he said, and she laughed, and her laughter was that of a child.

“I must give up climbing trees, must I not, Everard?”

“Indeed you must!”

“I shall have to behave with the greatest decorum? Shall we have a grand wedding, Everard … and when?”

“Soon,” said Everard.

“It must be soon.”

“Yes, I think so too. Soon… and I shall wear white and there will be a grand ceremony. Your father will marry us. Everard, do you think they will mind your marrying me?”

“Mind. Our families have always been friends, have they not?”

She clasped his arm.

“Of course! Of course!”

They were silent; he could feel her fingers pressing his arm, and her face was white in the moonlight.

“Is not life wonderful… wonderful,” she said.

“Happiness like this… such as I never dreamed of I Oh, what a mistake it is not to be happy when there is happiness all around you waiting to be taken!”

“We may not take what is not meant for us, darling,” said Everard gently.

“May we not? I would. I will snatch at it when no one is looking if need be.”

“You are a baby still, Carolan,” “No. Really I am very wise. But I am not good, like you, Everard. You would never take what was not meant for you. And it is because you are so different from me that I love you.”

They were silent while he kept his arm about her. She was holding his hand, kissing it, setting it against the cool skin other shoulder. She was full of innocent provocation. He was alarmed for her and for himself, and it was he who said they should go in; they had been in the summerhouse for a long time, and people would notice. Carolan herself had lost all sense of time; she had forgotten that others existed to notice.

But if Everard wished to go in, they must go in. As they walked across the lawn, she said fervently: “I shall be a good wife to you. Everard. I shall do everything you say … always. Oh, you will be surprised in me! So good I shall be … sedate and careful everything that you wish.”

Everard said: “But perhaps I would not wish you to be different from what you are.”

Her laughter echoed round them.

“Then, my sweet Everard, that will be very easy, very easy indeed.”

They had been gone a long time, and when they were back in the ballroom, curious glances were cast in their direction. Their flushed faces told their own story. Women smiled behind their fans; men’s eyes lighted up with amusement. Mrs. Orland’s face was blank with disapproval and disbelief. The squire’s was black as thunder. When he was in a rage he had no thought for the proprieties; he went across the ballroom to Carolan, and spoke to her in a voice which several people standing round him heard. Mrs. Orland drew Everard aside.

“You will go to your room at once,” said the squire.

“I will have an explanation of this disgusting behaviour.”

Carolan’s green eyes opened very wide.

“Oh, but..”

The squire lowered his voice slightly, but the fury in it was unmistakable.

“Go at once,” he said, ‘or I will take you.”

“I do not understand,” said Carolan.

“The ball is not over yet, and it is my first ball and I…”

“Evidently,” said the squire, ‘you have to learn how to behave, before you go to a ball. You behave like a kitchen girl. Get up to your room at once!”

She stared at the blue veins standing out on his forehead. And then Everard turned from his mother.

“Allow me to explain, Squire.” he said.

“It was entirely due to me…”

“Allow me to look after my own family, sir!” retorted the squire with murder in his eyes. Mrs. Orland, who above all things, dreaded gossip, plucked Everard’s sleeve.

“Everard, come with me quickly. The squire knows best where his daughter is concerned.”

Eyes were watching. The music was playing; couples watched as they danced: their eyes were full of amusement and speculation. The naughty little girl and the parson’s son! It was rather a good joke.

If you do not go to your room this minute,” said the squire between his teeth, “I will tear that contraption of lace and ribbons off you, and lay about you with my own hands here and now. I mean it, Madam. I repeat, go to your room.” Mrs. Orland’s eyes were pleading; Everard was undecided.

“I am going,” said Carolan, and the anger of the squire could not quell the happiness in her.

She went to her room. So this was the end of her first ball! She looked at herself in the mirror. Changed, she was grown up. She loved, and was loved; that had put colour into her eyes, a radiance on her face. Everard … wonderful, beautiful, clever, kind, good Everard loved her and they would be married. I will be so good, she thought, so good. She had almost forgotten her undignified retreat from the ballroom; she had almost forgotten the anger of the squire, until she heard his step outside her door. He burst in angrily, so that the door crashed against the side of the wall.

“Ah.” he said.

“Preening in front of the glass, eh?” And never, never in all her life at Haredon, had she seen him so angry. He shut the door behind him, and leaned against it, breathing heavily.

“Well?” he said.

“You absented yourself from the ballroom with that mollycoddle for nigh on two hours. What were you doing all that time?”

He came towards her threateningly.

“You had better tell me the truth!” he added. And his eyes rested on her bare shoulders, as though, she thought, he were seeing weals leaping up there as he applied the whip.

But happiness gave her courage, and even now she could not think of him so much as the sudden roughness in Everard’s voice, and the sudden quiver in his lips as they touched hers. This was nothing. Soon she would be Everard’s wife and out of reach of this brute whom she had tried to love and whom, she knew now. she had always hated and feared.

“I will tell you the truth!” she cried out. There is no need to hide it. Soon I shall be gone from here. Soon you will have no right to order me about as you did just now. I hate you for that… in front of them all. Everard and I are going to be married …”

“What!” His laughter was horrible.

“A chit of a girl, and without my consent! Ah! That is what he told you, eh?” He put his face close to hers, in that crude way he had.

“That is an old trick, my girl…” Horrible words came to his lips; he was saying foul things about her and Everard, and parsons and foolish girls. He was ugly, hateful, satanic. She flew at him suddenly, and struck him across his face. He roared with laughter, but not healthy laughter. He reached for her, but she was quick and agile; she had the bed between them.

“Oh,” she cried, panting, ‘what a wicked man you are! I always knew you were. None but the wicked could think such thoughts of Everard. You lie! I wonder your lies do not choke you. How I wish they would! How I should laugh! I hate you … I always have hated you. I hate you when you kiss me. There is something horrible about you …”

He interrupted her: “Girl! You forget yourself. Do you realize that you owe everything to me ?”

“To you I” “Yes,” he retorted, and his face was so full of blood that she thought it would burst, ‘to me! But for me you would have been born in the workhouse. You do not know your father. You were born ungrateful… you were born a harlot! I have brought you up as a lady, in comfort; I have given you all you could desire …” His voice broke with self-pity, but Carolan had no pity for him; she was as violent in hate as she was in love. And how she hated him for saying what he had just said about Everard!

“All I could desire!” she said.

“You! Do you think I forget how you treated me the night my mother went away!”

“You forget all I have given you. Was not that very dress you are wearing a present from me? You kissed me for it; it was cheap, was it not? Such a dress, and all for a kiss.”

“I wish I had never had it.”

He was trembling now. She was no longer a child he saw that, and he could have wept for it. He was losing her as surely as he had lost Bess and Kitty. Why did he always lose? He had tried so hard … first with one, then with the others.

“What happened in the summerhouse? Tell me that!” His voice was calmer now. He hoped he sounded like a father, anxious for his daughter.

“Everard asked me to marry him. and I said I would.”

“You… marry him! My dear child, he is going to marry Margaret.”

“How can that be, and he know nothing of it!”

“It has been arranged between our families for a long time.”

“He will not. He loves me.”

“Listen, Carrie, God knows I am fond of you … Carrie, you have no doubt of that, have you?”

She was silent.

“Carrie …” He began to move slowly towards her, but as she edged away he stopped.

“If you were, could you have behaved as you did tonight?” she demanded.

“Yes,” he said, ‘for that very reason. I thought he had taken you out there … You know what I thought and you no more than a child! I was angry with him and angry with you. I have been a father to you, Carrie. Do you not appreciate that?”

She wished he would not talk as though he were weeping. She wanted to be angry with him, and she could not.

“A father to you, Carrie,” he went on.

“Anxious for you, wanting the best for you. I do not think he would offer marriage; indeed I do not see how he can. It is known, my dear, that you are not my daughter; none knows who your father is. Your mother deceived me. It would not be well for a parson to marry you, Carrie. And he is all but affianced to Margaret.”

“Nothing will stand in our way,” said Carolan.

The squire murmured: “We must be calm, Carrie. We must talk of this. I must see Parson Orland. Dammed, I do not know; I do not know, I am sure.”

She was smiling now. This was nothing, this scene. The squire had been drinking too much, that was all. It was just a display of his violent temper.

He was rocking backwards and forwards on his heels.

“You can be sure, Carrie, of one thing. I shall do what I can for your happiness.”

He was looking at her pleadingly, but she was in no mood to forgive him. His horrible words still rang in her ears, spoiling the heavenly moonlight of the summerhouse. Her hands still tingled from the blows she had given him.

“Look here, Carrie, I lost my temper. Dammed, it is not the first time you have seen me lose my temper.”

She was laughing. She was not really the sort to nurse an injury. She would always be essentially generous, too generous perhaps.

“No,” she said with a charming gravity, “it is not the first time.”

“And will not be the last, I’ll warrant!” He slapped his thigh; one should not take his words seriously he was just a coarse old man.

“I suppose not.”

Then I am forgiven?” he asked, and thought, God damn it, is this Squire Haredon, asking a woman to forgive him?

“Then we are friends again?”

He looked so old, standing there, that she had not the heart to tell him she had never looked on him as a friend.

“Oh, yes,” she said, ‘friends. But never say such wicked things about Everard again.”

“Then come and kiss me just to show we are friends.”

She hesitated. How she hated these embraces! The roughness of his gestures, the feel of him, the smell of him repulsive.

“Come on, Carrie! I tell you I am going to help you. And, mind you, this is not going to be an easy matter with the Orlands.”

She went to him slowly, and lifted her face to brush his cheek with her lips, but he caught her suddenly in a grip that was like a vice about her slender body, and he kissed her full on the mouth; and even then he would not release her. She could feel his hot face against her own, smell spirits on his breath, hear his heavy breathing.

She tried to wriggle free, but he held her fast, laughing. She struck out then, for a panic had seized her.

“Put me down!” she said in a voice of ice.

“Put me down at once!”

He put her down; he was laughing thickly, and his voice seemed drugged and slurring.

“God damn it, Carrie, you have a temper. I could almost believe you are my daughter after all!”

He went out, and she ran to the door, leaning against it, listening to his footsteps as he went downstairs. He was thinking: Why not? She is no daughter of mine there is no relationship. Carrie, Carrie, little Carrie … lovelier than any of them.

And he knew then that he had never wanted her as a daughter, but as a woman.

Carolan was going away. Not openly but secretly. No one knew; not Margaret, nor the squire most definitely not the squire -not Mrs. West nor Mrs. Orland, nor even Everard … yet. But Everard would know, for of course she would tell Everard.

Who would have believed that such glorious happiness as she had known momentarily in the summerhouse should so quickly become tinged with grey! Everard’s love for her, she told herself, was like the sun shining on a grey day. It was there; obscured temporarily. For Everard had gone away; for three months he had gone away. ‘ How could he! How could he! she demanded of herself when he had told her. Would I have gone away?

Everard had said: “Always remember, Carolan, I love you. I shall come back for you. Whatever they say, I shall marry you, but just at present I must do what my parents wish. After all Carolan, what is three months?”

Three months, Carolan could have told him, is an eternity when you love. But when he said “What is three months?” just as though to him it could be no more than a matter of so many days and nights, he had wounded her deeply. And he had given in to his parents.

She would have been all for a midnight flitting, elopement, a speedy marriage anyhow, anywhere.

“My sweet Carolan!” he had said.

“You are hasty, but you are a child. What do you know of the world? I would have us begin our new Me together in a seemly fashion.”

And she stamped her foot and laughed and cried.

“Seemly! Is love to be a seemly matter then?”

To us, Carolan, yes; for love is marriage, and that is indeed a sacred thing.”

There she stood before him, her lips parted, her eyes ablaze. And he turned from her because there was something pagan in her that touched something pagan in him. and a man who has given his life to the church cannot be a pagan.

But the first great blazing glory had departed even before that. It was when the squire had come to her room no, it was not, for what did she care for the squire! It was when Margaret came and stood at the foot of her bed, her face ashen, her fingers plucking at the blue silk of her gown.