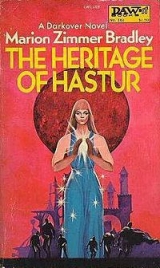

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Ramsay sounded harried. “Is it your contention that it is the Empire’s business, or mine, to police your ethical systems?”

“I always thought,” Callina said in her clear, still voice, “that ethical conduct was the responsibility of every honest man.”

Hastur said, “One of our fundamental laws, sir, however law is defined, is that the power to act confers the responsibility to do so. Is it otherwise with you?”

The Legate leaned his chin on his clasped hands. “I can admire that philosophy, my lord, but I must respectfully refuse to debate it with you. I am concerned at this moment with avoiding great inconvenience for both our societies. I will inquire into this matter and see what can legitimately be done without interfering in your political decisions. And if I may make a respectful suggestion, Lord Hastur, I suggest that you take this matter up directly with Kermiac of Aldaran. Perhaps you can persuade him of the rightness of your view, and he will take it upon himself to stop the traffic in weapons, in those areas where the final legal authority is his.”

The suggestion shocked me. Deal, negotiate, with that renegade Domain, exiled from Comyn generations ago? But no one seemed inordinately shocked at the idea. Hastur said, “We shall indeed discuss this matter with Lord Aldaran, sir. And it may be that since you refuse to take personal responsibility for enforcing the Empire’s agreement with all of Darkover, that I shall myself take the matter directly before the Supreme Tribunal of the Empire. If it is adjudged there that the agreement for Darkover does indeed require planet-wide enforcement of the Compact, Mr. Ramsay, have I then your assurance that you would enforce it?”

I wondered if the Legate was even conscious of the absolute contempt in Hastur’s voice for a man who required orders from a supreme authority to enforce ethical conduct. I felt almost ashamed of my Terran blood. But if Ramsay heard the contempt, he revealed nothing.

“If I receive orders to that effect, Lord Hastur, you may be assured that I will enforce them absolutely. And permit me to say, Lord Hastur, that it would in no way displease me to receive such orders.”

A few more words were exchanged, mostly formal courtesies. But the meeting was over, and I had to gather my scattered thoughts and reassemble the honor guard, conduct the Council members formally out of the headquarters building and the spaceport and through the streets of Thendara. I could sense my father’s thoughts, as I always could when we were in each other’s presence.

He was thinking that no doubt it would be left to him to go to Aldaran. Kermiac would have to receive him, if only as my mother’s kinsman. And I felt the utter weariness, like pain, in the thought. That journey into the Hellers was terrible, even in high summer; and summer was fast waning. Father was thinking that he could not shirk it. Hastur was too old. Dyan was no diplomat, he’d want to settle it by challenging Kermiac to a duel. But who else was there? The Ridenow lads were too young …

It seemed to me, as I followed my father through the streets of Thendara, that in fact almost everyone in Comyn was either too old or too young. What was to become of the Domains?

It would have been easier if I could have been wholly convinced that the Terrans were all evil and must be resisted. Yet against my will I had found much that was wise in what Ramsay said. Firm laws, and never too much power concentrated in one pair of hands, seemed to me a strong barrier to the kind of corruption we now faced. And a certain basic law to fall back on when the men could not be trusted. Men, as I had found out when Dyan was placed at the head of the cadets, were all too often fallible, acting from expediency rather than the honor they talked so much about. Ramsay might hesitate to act without orders, but at least he acted on the responsibility of men and laws he could trust to be wiser than himself. And there was a check on his power too, for he knew that if he acted on his own responsibility against the will of wiser heads, he would be removed before he could do too much damage. But who would be a check on Dyan’s power? Or my father’s? They had the power to act, and therefore the right to do it.

And who could question their motives, or call a halt to their acts?

previous | Table of Contents | next

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter SEVEN

The day remained clear and cloudless. At sunset Regis stood on the high balcony which looked out over the city and the spaceport. The dying sunlight turned the city at his feet to a gleaming pattern of red walls and faceted windows. Danilo said, “It looks like the magical city in the fairy tale.”

“There’s nothing much magical about it,” Regis said. “We learned that this morning on honor guard. Look, there’s the ship that takes off every night about this time. It’s too small to be an interstellar ship. I wonder where it’s going?”

“Port Chicago, perhaps, or Caer Donn. It must be strange to have to send messages to other people by writing them, instead of by using linked minds as we do through the towers,” Danilo said. “And it must feel very, very strange never to know what other people are thinking.”

Of course, Regis thought. Dani was a telepath. Suddenly he realized that he’d been in contact with him again and again, and it had seemed so normal that neither had recognized it as telepathy. Today at the Council had been different, terribly different. He must have laranafter all—but how and when, after Lew had failed?

And then the questions and the doubts came back. There had been so many telepaths there, spreading laraneverywhere, even a nontelepath might have picked it up. It did not necessarily mean anything. He felt wrung, half desperately hoping that he was not cut off anymore and half fearing.

He went on looking at the city spread out below. This was the hour off-duty, when if a cadet had incurred no demerit or punishment detail, he might go where he chose. Morning and early afternoon were spent in training, swordplay and unarmed combat, the various military and command skills they would need later as Guards in the city and in the field. Later in the afternoon, each cadet was assigned to special duties. Danilo, who wrote the clearest hand among the cadets, had been assigned to assist the supply-officer. Regis had the relatively menial task of walking patrol in the city with a seasoned veteran or two, keeping order in the streets, preventing brawls, discouraging sneak-thieves and footpads. He found that he liked it, liked the very idea of keeping order in the city of the Comyn.

Life in the cadet corps was not intolerable, as he had feared. He did not mind the hard beds, the coarse food, the continual demands on his time. He had been even more strictly disciplined at Nevarsin, and life in the barracks was easy by contrast. What troubled him most was always being surrounded by others and yet still being lonely, isolated from the others by a gulf he could not bridge.

From their first day, he and Danilo had drifted together, at first by chance, because their beds were side by side and neither of them had another close friend in the barracks. The officers soon began to pair them off for details needing partners like barrack room cleaning, which the cadets took in turns; and because Regis and Danilo were about the same size and weight, for unarmed-combat training and practice. Within the first-year group they were good-naturedly, if derisively, known as “the cloistered brethren” because, like the Nevarsin brothers, they spoke castaby choice, rather than cahuenga.

At first they spent much of their free time together too. Presently Regis noticed that Danilo sought his company less, and wondered if he had done something to offend the other boy. Then by chance he heard a second-year cadet jeeringly congratulating Danilo about his cleverness in choosing a friend. Something in Danilo’s face told him it was not the first time this taunt had been made. Regis had wanted to reveal himself and do something, defend Danilo, strike the older cadet, anything. On second thought he knew this would embarrass Danilo more and give a completely false impression. No taunt, he realized, could have hurt Danilo more. He was poor, indeed, but the Syrtis were an old and honorable family who had never needed to curry favor or patronage. From that day Regis began to make the overtures himself—not an easy thing to do, as he was diffident and agonizingly afraid of a rebuff. He tried to make it clear, at least to Danilo, that it was he who sought out Dani’s company, welcomed it and missed it when it was not offered. Today it was he who had suggested the balcony, high atop Comyn castle, where they could see the city and the spaceport.

The sun was sinking now, and the swift twilight began to race across the sky. Danilo said, “We’d better get back to barracks.” Regis was reluctant to leave the silence here, the sense of being at peace, but he knew Danilo was right. On a sudden impulse to confide, he said, “Dani, I want to tell you something. When I’ve spent my three years in the Guards—I must, I promised—I’m planning to go offworld. Into space. Into the Empire.”

Dani stared in surprise and wonder. “Why?”

Regis opened his mouth to pour out his reasons, and found himself suddenly at a loss for words. Why? He hardly knew. Except that it was a strange and different world, with the excitement of the unknown. A world that would not remind him at every turn that he had been born defrauded of his heritage, without laran. Yet, after today …

The thought was curiously disturbing. If in truth he had laran, then he hadno more reasons. But he still didn’t want to give up his dream. He couldn’t say it in words, but evidently Danilo did not expect any. He said, “You’re Hastur. Will they let you?”

“I have my grandfather’s pledge that after three years, if I still want to go, he will not oppose it.” He found himself thinking, with a stab of pain that if he had laranthey certainly would never let him go. The old breathless excitement of the unknown gripped him again; he shivered as he decided not to let them know.

Danilo smiled shyly and said, “I almost envy you. If my father weren’t so old, or if he had another son to look after him, I’d want to come with you. I wish we could go together.”

Regis smiled at him. He couldn’t find words to answer the warmth that gave him. But Danilo said regretfully, “He does need me, though. I can’t leave him while he’s alive. And anyway”—he laughed just a little—“from everything I’ve heard, our world is better than theirs.”

“Still, there must be things we can learn from them. Kennard Alton went to Terra and spent years there.”

“Yes,” Dani said thoughtfully, “but even after that, I notice, he came back.” He glanced at the sun and said, “We’re going to be late. I don’t want to get any demerits; we’d better hurry!”

It was dim in the stairwell that led down between the towers of the castle and neither of them saw a tall man coming down another staircase at an angle to this one, until they all collided, rather sharply, at its foot. The other man recovered first, reached out and took Regis firmly by the elbow, giving his arm a very faint twist. It was too dark to see, but Regis felt, through the touch, the feel and presence of Lew Alton. The experience was such a new thing, such a shock, that he blinked and could not move for a moment.

Lew said good-naturedly, “And now, if we were in the Guard hall, I’d dump you on the floor, just to teach you what to do when you’re surprised in the dark. Well, Regis, you do know you’re supposed to be alert even when you’re off duty, don’t you?”

Regis was still too shaken and surprised to speak. Lew let go his arm and said in sudden dismay, “Regis, did I really hurt you?”

“No—it’s just—” He found himself almost unable to speak because of his agitation. He had not seen Lew. He had not heard his voice. He had simply touched him, in the dark, and it was clearer than seeing and hearing. For some reason it filled him with an almost intolerable anxiety he did not understand.

Lew evidently sensed the distress he was feeling. He let him go and turned to Danilo, saying amiably, “Well, Dani, are you learning to walk with an eye to being surprised and thrown from behind?”

“Am I ever,” Danilo said, laughing. “Gabriel—Captain Lanart-Hastur—caught up with me yesterday. Thistime, though, I managed to block him, so he didn’t throw me. He just showed me the hold he’d used.”

Lew chuckled. “Gabriel is the best wrestler in the Guards,” he said. “I had to learn the hard way. I had bruises everywhere. Every one of the officers had me marked down as the easiest to throw. After my arm had been dislocated by—by accident,” he said, but Regis felt he had started to say something else, “Gabriel finally took pity on me and taught me a few of his secrets. Mostly, though, I relied on keeping out of the officers’ reach. At fourteen I was smaller than you, Dani.”

Regis’ distress was subsiding a little. He said, “It’s not so easy to keep out of the way, though.”

Lew said quietly, “I know. I suppose they have their reasons. It is good training, to keep your wits about you and be on the alert all the time; I was grateful for it later when I was on patrol and had to handle hefty drunks and brawlers twice my size. But I didn’t enjoy the learning, believe me. I remember Father saying to me once that it was better to be hurt a little by a friend than seriously hurt, some day, by an enemy.”

“I don’t mind being hurt,” said Danilo, and with that new and unendurable awareness, Regis realized his voice was trembling as if he was about to cry. “I was bruised all over when I was learning to ride. I can stand the bruises. What I do mind is when—when someone thinks it’s funny to see me take a fall. I didn’t mind it when Lerrys Ridenow caught me and threw me halfway down the stairs yesterday, because he said that was always the most dangerous place to be attacked and I should always be on guard in such a spot. I don’t mind when they’re trying to teach me something. That’s what I’m here for. But now and then someone seems to—to enjoy hurting me, or frightening me.”

They had come away from the stairs now and were walking along an open collonade; Regis could see Lew’s face, and it was grim. He said, “I know that happens. I don’t understand it either. And I’ve never understood why some people seem to feel that making a boy into a man seems to mean making him into a brute. If we’d all been in the Guard hall, I’d have felt compelled to throw Regis ten feet, and I don’t suppose I’d have been any gentler than any other officer. But I don’t like hurting people when there’s no need either. I suppose your cadet-master would think me shamefully remiss in my duty. Don’t tell him, will you?” He grinned suddenly and his hand fell briefly on Danilo’s shoulder, giving him a little shake. “Now you two had better hurry along; you’ll be late.” He turned a corridor at right angles to their own and strode away.

The two cadets hurried down their own way. Regis was thinking that he had never known Lew felt like that. They must have been hard on him, especially Dyan. But how did he know that?

Danilo said, “I wish all the officers were like Lew. I wish he were the cadet-master, don’t you?”

Regis nodded. “I don’t think Lew would want to be cadet-master, though. And from what I’ve heard, Dyan is very serious about honor and responsibility. You heard him speak at Council.”

Danilo’s mouth twisted. “Anyhow, you don’t have to worry. Lord Dyan likes you. Everybody knows that!”

“Jealous?” Regis retorted good-naturedly.

“You’re Comyn,” Danilo said, “you get special treatment.”

The words were a sudden painful reminder of the distance between them, a distance Regis had almost ceased to feel. It hurt. He said, “Dani, don’t be a fool! You mean the fact that he uses me for a partner at sword practice? That’s an honor I’d gladly change with you! If you think it’s love-pats I’m getting from him, take a look at me naked some day—you’re welcome and more than welcome to Dyan’s love-pats!”

He was completely unprepared for the dark crimson flush that flooded Danilo’s face, the sudden fierce anger as he swung around to face Regis. “What the hell do you mean by thatremark?”

Regis stared at him in dismay. “Why, only that sword-practice with Lord Dyan is an honor I’d gladly do without. He’s much stricter than the arms-master and he hits harder! Look at my ribs, you’ll see that I’m black and blue from shoulder to knee! What did you think I meant?”

Danilo turned away and didn’t answer directly. He only said, “We’re going to be late. We’d better run.”

Regis spent the early evening hours on street-patrol in the city with Hjalmar, the giant young Guardsman who had first tested him for swordplay. They broke up two budding brawls, hauled an obstreperous drunk to the brig, directed half a dozen lost country bumpkins to the inn where they had left their horses and gently reminded a few wandering women that harlots were restricted by law to certain districts in the city. A quiet evening in Thendara. When they returned to the Guard hall to go off duty, they fell in with Gabriel Lanart and half a dozen officers who were planning to visit a small tavern near the gates. Regis was about to withdraw when Gabriel stopped him.

“Come along with us, brother. You should see more of the city than you can from the barracks window!”

Thus urged, Regis went with the older men. The tavern was small and smoky, filled with off-duty Guardsmen. Regis sat next to Gabriel, who took the trouble to teach him the card game they were playing. It was the first time he had been in the company of older officers. Most of the time he was quiet, listening much more than he talked, but it was good to be one of the company and accepted.

It reminded him, just a little, of the summers he’d spent at Armida. It would never have occurred to Kennard or Lew or old Andres to treat the solemn and precocious boy as a child. That early acceptance among men had put him out of step, probably forever, he realized with a remote sadness, with lads his own age. Now though, and the knowledge felt as if a weight had fallen from him, he knew that he did feel at home among men. He felt as if he was drawing the first really free breaths he had drawn since his grandfather pushed him, with only a few minutes to prepare for it, into the cadets.

“You’re quiet, kinsman,” Gabriel said as they walked back together. “Have you had too much to drink? You’d better go and get some sleep. You’ll be all right tomorrow.” He said a good-natured good night and went off to his own quarters.

The night officer patrolling the court said, “You’re a few minutes late, cadet. It’s your first offense, so I won’t put you on report this time. Just don’t do it again. Lights are out in the first-year barracks; you’ll have to undress in the dark.”

Regis made his way, a little unsteadily, into the barracks. Gabriel was right, he thought, surprised and not altogether displeased, he had had too much to drink. He was not used to drinking at all, and tonight he had drunk several cups of wine. He realized, as he hauled off his clothes by the moonlight, that he felt confused and unfocused. It had, he thought with a strange fuzziness, been a meaningful day, but he didn’t know yet what it all meant. The Council. The somehow shocking realization that he had reached his grandfather’s mind, recognized Lew by touch without seeing or hearing him. The odd half-quarrel with Danilo. It added to the confusion he felt, which was more than just drunkenness. He wondered if they had put kirianin his wine, heard himself giggle aloud at the thought, then fell rapidly into an edgy, nightmare-ridden half-sleep.

… He was back in Nevarsin, in the cold student dormitory where, in winter, snow drifted through the wooden shutters and lay in heaps on the novices’ beds. In his dream, as had actually happened once or twice, two or three of the students had climbed into bed together, sharing blankets and body warmth against the bitter cold, to be discovered in the morning and severely scolded for breaking this inflexible rule. This dream kept recurring; each time, he would discover some strange naked body in his arms and, deeply disturbed, he would wake up with an admixture of fear and guilt. Each time he woke from this repeated dream he was more deeply upset and troubled by it, until he finally escaped into a deeper, darker realm of sleep. Now it seemed that he was his own father, crouched on a bare hillside in darkness, with strange fires exploding around him. He was shuddering with fright as men dropped dead around him, closer and closer, knowing that within moments he too would be blasted into fragments by one of the erupting fires. Then he felt someone close to him in the dark, holding him, sheltering his body with his own. Regis started awake again, shaking. He rubbed his eyes and looked around him at the quiet barracks room, dimly lit with moonlight, seeing the dim forms of the other cadets, snoring or muttering in their sleep. None of it was real, he thought, and slid down again on his hard mattress.

After a while he began to dream again. This time he was wandering in a featureless gray landscape in which there was nothing to see. Someone was crying somewhere in the gray spaces, crying miserably, in long painful sobs. Regis kept turning in another direction, not at first sure whether he was looking for the source of the weeping or trying to get away from the wretched sound. Small shuddering words came through the sobs, I won’t, I don’t want to, I can’t.Every time the crying lessened for a moment there was a cruel voice, an almost familiar voice, saying, Oh, yes you will, you know you cannot fight me, and at other times, Hate me as much as you will, I like it better that way. Regis squirmed with fear. Then he was alone with the weeping, the inarticulate little sobs of protest and pleading. He went on searching in the lonely grayness until a hand touched him in the dark, a rude indecent searching, half painful and half exciting. He cried out “No!” and fled again into deeper sleep.

This time he dreamed he was in the student’s court at Nevarsin, practicing with the wooden foils. Regis could hear the sound of his own panting breaths, doubled and multiplied in the great echoing room as a faceless opponent moved before him and kept quickening his movements insistently. Suddenly Regis realized they were both naked, that the blows struck were landing on his bare body. As his faceless opponent moved faster and faster Regis himself grew almost paralyzed, sluggishly unable to lift his sword. And then a great ringing voice forbade them to continue, and Regis dropped his sword and looked up at the dark cowl of the forbidding monk. But it was not the novice-master at Nevarsin monastery, but Dyan Ardais. While Regis stood, frozen with dread, Dyan picked up the dropped sword, no longer a wooden practice sword, but a cruelly sharpened rapier. Dyan, holding it out straight ahead while Regis looked on in dread and horror, plunged it right into Regis’ breast. Curiously, it went in without the slightest pain, and Regis looked down in shaking dread at the sight of the sword passing through his entire body. “That’s because it didn’t touch the heart,” Dyan said, and Regis woke with a gasping cry, pulling himself upright in bed. “Zandru,” he whispered, wiping sweat from his forehead, “what a nightmare!” He realized that his heart was still pounding, and then that his thighs and his sheets were damp with a clammy stickiness. Now that he was wide awake and knew what had happened, he could almost laugh at the absurdity of the dream, but it still gripped him so that he could not lie down and go to sleep again.

It was quiet in the barrack room, with more than an hour to go before daybreak. He was no longer drunk or fuzzy-headed, but there was a pounding pain behind his eyes.

Slowly he became aware that Danilo was crying in the next bed, crying helplessly, desperately, with a kind of hopeless pain. He remembered the crying in his dream. Had he heard the sound, woven it into nightmare?

Then, in a sort of slow amazement and wonder, he realized that Danilo was not crying.

He could see, by the dimmed moonlight, that Danilo was in fact motionless and deeply asleep. He could hear his breath coming softly, evenly, see his turned-away shoulder moving gently with his breathing. The weeping was not a sound at all, but a sort of intangible pattern of vibrating misery and despair, like the lost little crying in his dream, but soundless.

Regis put his hands over his eyes in the darkness and thought, with rising wonder, that he hadn’t heard the crying, but knewit just the same.

It was true, then. Laran. Not randomly picked up from another telepath, but his.

The shock of that thought drove everything else from his mind. How did it happen? When? And formulating the question brought its own answer: that first day in barracks, when Dani had touched him. He had dreamed about that conversation tonight, dreaming he was his father for a moment. Again he felt that surge of closeness, of emotion so intense that there was a lump in his throat. Danilo slept quietly now, even the telepathic impression of noiseless weeping having died away. Regis worried, troubled and torn with even the backwash of his friend’s grief, wondering what was wrong.

Quickly he shut off the curiosity. Lew had said that you learned to keep your distance, in order to survive. It was a strange, sad thought. He could not spy on his friend’s privacy, yet he was still near to tears at the awareness of Dani’s misery. He had sensed it, earlier that day, when Lew talked to them. Had someone hurt him, ill-treated him?

Or was it simply that Danilo was lonely, homesick, wanting his family? Regis knew so little about him.

He recalled his own early days at Nevarsin. Cold and lonely, heartsick, friendless, hating his family for sending him here, only a fierce remnant of Hastur pride had kept him from crying himself to sleep every night for a long time.

For some reason that thought filled him again with an almost unendurable sense of anxiety, fear, restlessness. He looked across at Danilo and wished he could talk to him about this. Dani had been through it; he would know. Regis knew he would have to tell someone soon. But who should he tell? His grandfather? The sudden realization of his own laranhad left Regis strangely vulnerable, shaken again and again by waves of emotion; again he was at the edge of tears, this time for his grandfather, reliving that fierce, searing moment of anguish of his only son’s terrible death.

And, still vulnerable, he swung from grief to rebellion. He was sure his grandfather would force him to walk the path ready-made for a Hastur heir with laran. He would never be free! Again he saw the great ship taking off for the stars, and his whole heart, his body, his mind, strained to follow it outward into the unknown. If he cherished that dream, he could never tell his grandfather at all.

But he could share it with Dani. He literally ached to step across the brief space between their beds, slip into bed beside him, share with him this incredible dual experience of grief and tremendous joy. But he held himself back, recalling with an imperative strange sharpness what Lew had said; it was like living with your skin off. How could he impose this burden of his own emotions on Dani, who was himself so burdened with unknown sorrow, so troubled and nightmare-driven that his unshed tears penetrated even into Regis’ dreams as a sound of weeping? If he was to have the telepathic gift, Regis thought sadly, he had to learn to live by the rules of the telepath. He realized that he was cold and cramped, and crawled under his blankets again. He huddled them around him, feeling lonely and sad. He felt curiously unfocused again, drifting in anxious search, but in answer to his questioning mind he saw only flimsy pictures in imagination, men and strange nonhumans fighting along a narrow rock-ledge; the faces of two little children fair and delicate and baby-blurred in sleep, then cold in death with a grief almost too terrible to be borne; dancing figures whirling, whirling like wind-blown leaves in a mad ecstasy; a great towering form, blazing with fire …

Exhausted with emotion, he slept again.

previous | Table of Contents | next