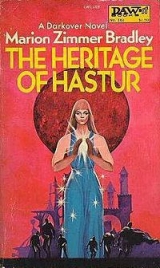

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter TWENTY-THREE

“It’s not threshold sickness this time, bredu,” Regis said, raising his head from the matrix. “This time I’m doing it right, but I can’t see anything but the … the image that struck me down on the northward road. The fire and the golden image. Sharra.”

Danilo said, shuddering, “I know. I saw it too.”

“At least it didn’t strike me senseless this time.” Regis covered the matrix. It roused no sickness in him now, just an overwhelming sense of heightened perception. He should have been able to reach Kennard, or someone at Arilinn, but there was nothing—nothing but the great, burning, chained image he knew to be Sharra.

Yes, something terrible was happening in the hills. Danilo said, “I’d think every telepath on Darkover must know it by now, Regis. Don’t they keep a lookout for such things in the towers? No need for you to feel guilty because you can’t do it alone, without training.”

“I don’t feel exactly guilty, but I am dreadfully worried. I tried to reach Lew, too. And couldn’t.”

“Maybe he’s safe at Arilinn, behind their force-field.”

Regis wished he could think so. His head was clear and he knew the sickness would not return, but the reappearance of the image of Sharra troubled him deeply. He had heard stories of out-of-control matrices, most of them from the Ages of Chaos, but some more recent. A cloud covered the sun and he shivered with cold.

Danilo said, “I think we should ride on, if you’ve finished.”

“Finished? I didn’t even start,” he said ruefully, tucking the matrix into his pocket again. “We’ll go on, but let me eat something first.” He accepted the chunk of dried meat Danilo handed him and sat chewing it. They were sitting side by side on a fallen tree, their horses cropping grass nearby through the melting snow. “How long have we been on the road, Dani? I lost count while I was sick.”

“Six days, I think. We aren’t more than a few days from Thendara. Perhaps tonight we’ll be within the outskirts of the Armida lands and I can send word somehow to my father. Lew told Beltran’s men to send word, but I don’t trust him to have done it.”

“Grandfather always regarded Lord Kermiac as an honorable man. Beltran is a strange cub to come from such a den.”

“He may have been decent enough until he fell into the hands of Sharra,” Danilo said. “Or perhaps Kermiac ruled too long. I’ve heard that the land which lives too long under the rule of old men grows desperate for change at any cost.”

Regis wondered what would happen in the Domains when his grandfather’s regency ended, when Prince Derik Elhalyn took his crown. Would his people have grown desperate for change at any cost? He was remembering the Comyn Council where he and Danilo had stood watching the struggle for power. They would not be watching, then, they would be part of it. Was power always evil, always corrupt?

Dani said, as though he knew Regis’ thoughts, “But Beltran didn’t just want power to change things, he wanted a whole world to play with.”

Regis was startled at the clarity of that and pleased again to think that, if the fate of their world ever depended on the Hasturs, he would have someone like Dani to help him with decisions! He reached out, gave Danilo’s hand a brief, strong squeeze. All he said was, “Let’s get the horses saddled, then. Maybe we can help make sure he doesn’t get it to play with.”

They were about to mount when they heard a faint droning, which grew to a sky-filling roar. Danilo glanced up; without a word, he and Regis drew and the horses under the cover of the trees. But the helicopter, moving steadily overhead, paid no attention to them.

“Nothing to do with us,” said Danilo when it was out of sight, “probably some business of the Terrans.” He let out his breath and laughed, almost in apology. “I shall never hear one again without fear!”

“Just the same, a day will come when we’ll have to use them too,” Regis said slowly. “Maybe the Aldaran lands and the Domains would understand each other better if it were not ten days’ ride from Thendara to Caer Donn.”

“Maybe.” But Regis felt Danilo withdraw, and he said no more. As they rode on, he thought that, like it or not, the Terrans were here and nothing could ever be as it was before they came. What Beltran wanted was not wrong, Regis felt. Only the way he chose to get it. He himself would find a safer way.

He realized, with astonishment and self-disgust, the direction his thoughts were taking. What had he to do with all that?

He had ridden this road from Nevarsin less than a year ago, believing then that he was without laranand free to shrug his heritage aside and go out into space, follow the Terran starships to the far ends of the Empire. He looked up at the face of Liriel, pale-violet in the noonday sky, and thought how no Darkovan had ever set foot even on any of their own moons. His grandfather had pledged to help him go, if Regis still wanted to. He would not break his word.

Two years more, given to the cadets and the Comyn. Then he would be free. Yet an invisible weight seemed to press him down, even as he made plans for freedom.

Danilo drew his horse suddenly to a stop.

“Riders, Lord Regis. On the road ahead.”

Regis drew even with him, letting his reins lie loose on his pony’s neck. “Should we get off the road?”

“I think not. We are well within the Domains by now; here you are safe, Lord Regis.”

Regis lifted his eyebrows at the formal tone, suddenly realizing its import. In the isolation of the last days, in stress and extremity, all man-made barriers had fallen; they were two boys the same age, friends, bredin. Now, in the Domains and before outsiders once again, he was the heir to Hastur, Danilo his paxman. He smiled a little ruefully, accepting the necessity of this, and let Danilo ride a few paces ahead. Looking at his friend’s back, he thought with a strange shiver that it was literally true, not just a word: Dani would die for him.

It was a terrifying thought, though it should not have been so strange. He knew perfectly well that any one of the Guardsmen who had escorted him here and there when he was only a sickly little boy, or ridden with him to and from Nevarsin, were sworn by many oaths to protect him with their lives. But it had never been entirely real to him until Danilo, of his free will and from love, had given him that pledge. He rode steadily, with the trained control he had been taught, but his back was alive with prickles and he felt the very hairs rise on his forearms. Was this what it meant, to be Hastur?

He could see the riders now. The first few wore the green-and-black uniform he had worn himself in the past summer. Comyn Guardsmen! And a whole group of others, not in uniform. But there were no banners, no displays. This was a party of war. Or, at least, one prepared to fight!

Ordinary travelers would have drawn off the road, letting the Guardsmen pass. Instead Regis and Danilo rode straight toward them at a steady pace. The head Guardsman—Regis recognized him now, the young officer Hjalmar—lowered his pike and gave formal challenge.

“Who rides in the Domains—” He broke off, forgetting the proper words. “Lord Regis!”

Gabriel Lanart-Hastur rode quickly past him, bringing his horse up beside Regis. He reached both hands to him. “Praise to the Lord of Light, you are safe! Javanne has been mad with fear for you!”

Regis realized that Gabriel would have been blamed for letting him ride off alone. He owed him an apology. There was no time for it now. The riders surrounded them and he noted many members of the Comyn Council among Guardsmen and others he did not recognize. At the head of them, on a great gray horse, rode Dyan Ardais. His stern, proud face relaxed a little as he saw Regis, and he said in his harsh but musical voice, “You have given us all a fright, kinsman. We feared you dead or prisoner somewhere in the hills.” His eyes fell on Danilo and his face stiffened, but he said steadily, “ DomSyrtis, word came from Thendara, sent by the Terrans and brought to us; a message was sent to your father, sir, that you were alive and well.”

Danilo inclined his head, saying with frigid formality, “I am grateful, Lord Ardais.” Regis could tell how hard the civil words came. He looked at Dyan with faint curiosity, surprised at the prompt delivery of the reassuring message, wondering why, at least, Dyan had not left it to a subordinate to give. Then he knew the answer. Dyan was in charge of this mission, and would consider it his duty.

Whatever his personal faults and struggles, Regis knew, Dyan’s allegiance to Comyn came first. Whatever he did, everything was subordinate to that. It had probably never occurred to Dyan that his private life could affect the honor of the Comyn. It was an unwelcome thought and Regis tried to reject it, but it was there nevertheless. And, even more disquieting, the thought that if Danilo had been a private citizen and not a cadet, it genuinely would nothave mattered how Dyan treated or mistreated him.

Dyan was evidently waiting for some explanation; Regis said, “Danilo and I were held prisoner at Aldaran. We were freed by DomLewis Alton.” Lew’s formal title had a strange sound in his ears. He did not remember using it before.

Dyan turned his head, and Regis saw the horse-litter at the center of the column. His grandfather? Traveling at this season? Then, with the curiously extended senses he was just beginning to learn how to use, he knew it was Kennard, even before Dyan spoke.

“Your son is safe, Kennard. A traitor, perhaps, but safe.”

“He is no traitor,” Regis protested. “He too was held a prisoner. He freed us in his own escape.” He held back the knowledge that Lew had been tortured, but Kennard knew it anyway: Regis could not yet barricade himself properly.

Kennard put aside the leather curtains. He said, “Word came from Arilinn—you know what is going on at Aldaran? The raising of Sharra?”

Regis saw that Kennard’s hands were still swollen, his body bent and bowed. He said, “I am sorry to see you too ill to ride, Uncle.” In his mind, the sharpest of pains, was the memory of Kennard as he had been during those early years at Armida, as Regis had seen him in the gray world. Tall and straight and strong, breaking his own horses for the pleasure of it, directing the men on the fire-lines with the wisdom of the best of commanders and working as hard as any of them. Unshed tears stung Regis’ eyes for the man who was closest to a father to him. His emotions were swimming near the surface these days, and he wanted to weep for Kennard’s suffering. But he controlled himself, bowing from his horse over his kinsman’s crippled hand.

Kennard said, “Lew and I parted with harsh words, but I could not believe him traitor. I do not want war with Lord Kermiac—”

“Lord Kermiac is dead, Uncle. Lew was an honored guest to him. After his death, though, Beltran and Lew quarreled. Lew refused … ” Quietly, riding beside Kennard’s litter, Regis told him everything he knew of Sharra, up to the moment when Lew had pleaded with Beltran to renounce his intention, and promising to enlist the help of Comyn Council … and how Beltran had treated them all afterward. Kennard’s eyes closed in pain when Regis told of how Kadarin had brutally beaten his son, but it would not have occurred to Regis to spare him. Kennard was a telepath, too.

When he ended, telling Kennard how Lew had freed them with Marjorie’s aid, Kennard nodded grimly. “We had hoped Sharra was laid forever in the keeping of the forge-folk. While it was safely at rest, we would not deprive them of their goddess.”

“A piece of sentiment likely to cost us dear,” Dyan said. “The boy seems to have behaved with more courage than I had believed he had. Now the question is, what’s to be done?”

“You said that word came from Arilinn, Uncle. Lew is safe there, then?”

“He is not at Arilinn, and the Keeper there, seeking, could not find him. I fear he has been recaptured. Word came, saying only that Sharra had been raised and was raging in the Hellers. We gathered every telepath we could find outside the towers, in the hope that somehow we could control it. Nothing less could have brought me out now,” he added, with a detached glance at his crippled hands and feet, “but I am tower-trained and probably know more of matrix work than anyone not actually inside a tower.”

Regis, riding at his side, wondered if Kennard was strong enough. Could he actually face Sharra?

Kennard answered his unspoken words. “I don’t know, son,” he said aloud, “but I’m going to have to try. I only hope I need not face Lew, if he has been forced into Sharra again. He is my son, and I do not want to face him as an enemy,” His face hardened with determination and grief. “But I will if I must.” And Regis heard the unspoken part of that, too: Even if I must kill him this time.

previous | Table of Contents | next

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter TWENTY-FOUR

(Lew Alton’s narrative concluded)

To this day I have never known or been able to guess how long I was kept under the drug Kadarin had forced on me. There was no period of transition, no time of incomplete focus. One day my head suddenly cleared and I found myself sitting in a chair in the guest suite at Aldaran, calmly putting on my boots. One boot was on and one was off, but I had no memory of having put on the first, or what I had been doing before that.

I raised my hands slowly to my face. The last clear memory I had was of swallowing the drug Kadarin had given me. Everything after that had been dreamlike, hallucinatory quasi-memories of hatred and lust, fire and frenzy. I knew time had elapsed but I had no idea how much. When I swallowed the drug, my face had been bleeding after Kadarin had ripped it to ribbons with his heavy fists. Now my face was tender, with raised welts still sore and painful, but all the wounds were closed and healing. A sharp pain in my right hand, where I bore the long-healed matrix burn from my first year at Arilinn, made me flinch and turn the hand over. I looked, without understanding, at the palm. For three years and more, it had been a coin-sized white scar, a small ugly puckered patch with a couple of scarred seams at either side. That was what it had been.

Now—I stared, absolutely without comprehension. The white patch was gone, or rather, it had been replaced by a raw, red, festering burn half the breadth of my palm. It hurt like hell.

What had I been doing with it? At the back of my mind I was absolutely certain that I had been lying here, hallucinating, during all that time. Instead I was up and half dressed. What in the hell was going on?

I went into the bath and stared into a large cracked mirror.

The face which looked out at me was not mine.

My mind reeled for a moment, teetering at the edge of madness. Then I slowly realized that the eyes, the hair, the familiar brows and chin were there. But the face itself was a ghastly network of intersection scars, flaming red weals, blackened bluish welts and ridges. One lip had been twisted up and healed, puckered and drawn, giving me a hideous permanent sneer. There were stray threads of gray in my hair; I looked years older. I wondered, suddenly, in insane panic, if they had kept me here drugged while I grew old …

I calmed the sudden surge of panic. I was wearing the same clothes I had worn when I was captured. They were crushed and dirty, but not frayed or threadbare. Only long enough for my wounds from the beating to heal, then, and for me to acquire some new ones somehow, and that atrocious burn on my hand, I turned away from the mirror with a last rueful glance at the ruin of my face. Whatever pretensions to good looks I might ever have had, they were gone forever. A lot of those scars had healed, which meant they’d never look any better than they did now.

My matrix was back in its bag around my neck, though the thong Kadarin had cut had been replaced with a narrow red silk cord. I fumbled to take it out. Before I had the stone bared, the image flared, golden, burning … Sharra!With a shudder of horror, I thrust it away again.

What had happened? Where was Marjorie?

Either the thought had called her to me or had been summoned by her approaching presence. I heard the creaking of the door-bolts again and she came into the room and stopped, staring at me with a strange fear. My heart sank down into my boot soles. Had that dream, of all the dreams, been true? For an aching moment I wished we had both died together in the forests. Worse than torture, worse than death, to see Marjorie look at me with fear …

Then she said, “Thank God! You’re awake this time and you know me!” and ran straight into my arms. I strained her to me. I wanted never to let her go again. She was sobbing. “It’s really you again! All this time, you’ve never looked at me, not once, only at the matrix … ”

Cold horror flooded me. Then some of it had been true. I said, “I don’t remember anything, Marjorie, nothing at all since Kadarin drugged me. For all I know, I have been in this room all that time. What do you mean?”

I felt her trembling. “You don’t remember anyof it? Not the forge-folk, not even the fire at Caer Donn?”

My knees began to collapse under me; I sank on the bed and heard my voice cracking as I said, “I remember nothing, nothing, only terrible ghastly dreams … ” The implications of Marjorie’s words turned me sick. With a fierce effort I controlled the interior heaving and managed to whisper, “I swear, I remember nothing, nothing. Whatever I may have done … Tell me, in Zandru’s name, did I hurt you, mishandle you?”

She put her arms around me again and said, “You haven’t even lookedat me. Far less touched me. That was why I said I couldn’t go on.” Her voice died. She put her hand on mine. I cried out with the pain and she quickly caught it up, saying tenderly, “Your poor hand!” She looked at it carefully. “It’s better, though, it’s much better.”

I didn’t like to think what it must have been, if this was better. No wonder fire had flamed, burned, raged through all my nightmares! But how, in the name of all the devils in all the hells, had I done this?

There was only one answer. Sharra. Kadarin had somehow forced me back into the service of Sharra. But how, how?How could he use the skills of my brain while my conscious mind was elsewhere? I’d have sworn it was impossible. Matrix work takes deliberate, conscious concentration … My fists clenched. At the searing pain in my palm I unclenched them again, slowly.

He dared! He dared to steal my mind, my consciousness …

But how? How?

There was only one answer, only one thing he could have done; use all the free-floating rage, hatred, compulsion in my mind, when my conscious control was gone—and take all that and channel it through Sharra!All my burning hatred, all the frenzies of my unconscious, freed of the discipline I kept on them, fed through that vicious thing.

He had done that to me, while my own conscious mind was in abeyance. Next to that, Dyan’s crime was a boy’s prank. The ruin of my face, the burn of my hand, these were nothing, nothing. He had stolen my conscious mind, he had usedmy unconscious, uncontrolled, repressed passions … Horrible!

I asked Marjorie, “Did they force you, too, into Sharra?” She shivered. “I don’t want to talk about it, Lew,” she said, whimpering like a hurt puppy. “Please, no, no. Just … just let’s be together for now.”

I drew her down on the bed beside me, held her gently in the circle of my arms. My thoughts were grim. She stroked her light fingers across my battered face and I could feel her horror at the touch of the scars. I said, my voice thick in my throat, “Is my face so … so repulsive to you?”

She bent down and laid her lips against the scars. She said with that simplicity which, more than anything else, meant Marjorieto me, “You could never be horrible to me, Lew. I was only thinking of the pain you have suffered, my darling.”

“Fortunately I don’t remember much of it,” I said. How long would we be here uninterrupted? I knew without asking that we were both prisoners now, that there was no hope of any such trick as we had managed before. It was hopeless. Kadarin, it seemed, could force us to do anything. Anything!

I held her tight, with a helpless anguish. I think it was then that I knew, for the first time, what impotence meant, the chilling, total helplessness of true impotence.

I had never wanted personal power. Even when it was thrust on me, I had tried to renounce it. And now I could not even protect this girl, my wife, from whatever tortures, mental or physical, Kadarin wanted to inflict on her.

All my life I had been submissive, willing to be ruled, willing to discipline my anger, to accept continence at the peak of early manhood, bending my head to whatever lawful yoke was placed on it.

And now I was helpless, bound hand and foot. What they had done they could do again … And now, when I needed strength, I was truly impotent …

I said, “Beloved, I’d rather die than hurt you, but I mustknow what has been going on.” I did not ask about Sharra. Her trembling was answer enough. “How did he happen to let you come to me now, after so long?”

She controlled her sobs and said, “I told him—and he knew I meant it—that unless he freed your mind, and let us be together, I would kill myself. I can still do that and he cannot prevent me.”

I felt myself shudder. It went all the way to the bone. She went on, keeping her voice quiet and matter-of-fact, and only I, who knew what discipline had made her a Keeper, could have guessed what it cost her. “He can’t control the … the matrix, the thing, without me. And under drugs I can’t do it at all. He tried, but it didn’t work. So I have that last hold over him. He will do almost anything to keep me from killing myself. I know I should have done it. But I had to”—her voice finally cracked, just a little—“to see you again when you knew me, ask you … ”

I was more desperately frightened than ever. I asked, “Does Kadarin know that we have lain together?”

She shook her head. “I tried to tell him. I think he hears only what he wants to hear now. He is quite mad, you know. It would not matter to him anyway, he thinks it is only Comyn superstition.” She bit her lip and said, “And it cannot be as dangerous as you think, I am still alive, and well.”

Not well, I thought, looking at her pallor, the faint bluish lines around her mouth. Alive, yes. But how long could she endure this? Would Kadarin spare her, or would he use her all the more ruthlessly to achieve his aims—whatever, in his madness, they were now—before her frail body gave way?

Did he even know he was killing her? Had he even bothered to have her monitored?

“You spoke of a fire at Caer Donn … ?”

“But you were there, Lew. You really don’t remember?”

“I don’t. Only fragments of dreams. Terrible nightmares.”

She lightly touched the horrible burn on my hand. “You got this there. Beltran made an ultimatum. It was not his own will—he has tried to get away—but I think he is helpless in Kadarin’s hands now too. He made threats and the Terrans refused, and Kadarin took us up to the highest part of the city, where you can look straight down into the city, and—oh, God, Lew, it was terrible, terrible, the fire striking into the heart of the city, the flames rising everywhere, screams … ” She rolled over, hiding her head in the pillow. She said, muffled, “I can’t. I can’t tell you. Sharra is horrible enough, but this, the fire … I never dreamed, never imagined … And he said next time it would be the spaceport and the ships!”

Caer Donn. Our magical dream city. The city I had seen transformed by a synthesis of Terran science and Darkovan psi powers. Shattered, burned. Lying in ruins.

Like our lives, like our lives … And Marjorie and I had done it.

Marjorie was sobbing uncontrollably. “I should have died first. I will die before I use that—that destruction again!”

I lay holding her close. I could see the seal of Comyn, deeply marked in my wrist a few inches above the dreadful flaming burn. There was no hope for me now. I was traitor, doubly condemned and traitor.

For a moment, time reeling in my mind, I knelt before the Keeper at Arilinn and heard my own words: “ … swear upon my life that what powers I may attain shall be used only for the good of my caste and my people, never for personal gain or personal ends … ”

I was forsworn, doubly forsworn. I had used my inborn talents, my tower-trained skills, to bring ruin, destruction on those I was doubly sworn, as Comyn, as tower telepath, to safeguard and protect.

Marjorie and I were deeply in rapport. She looked at me, her eyes wide in horror and protest. “You did not do it willingly,” she whispered. “You were forced, drugged, tortured—”

“That makes no difference.” It was my own rage, my own hate, they had used. “Even to save my life, even to save yours, I should never have let them bring us back. I should have made him kill us both.”

There was no hope for either of us now, no escape. Kadarin could drug me again, force me again, and there was no way to resist him. My own unknown hatred had set me at his mercy and there was no escape.

No escape except death.

Marjorie—I looked at her, wrung with anguish. There was no escape for her either. I should have made Kadarin kill her quickly, there in the stone hut. Then she would have died clean, not like this, slowly, forced to kill.

She fumbled at the waist of her dress, and brought out a small, sharp dagger. She said quietly, “I think they forgot I still have this. Is it sharp enough, Lew? Will it do for both of us, do you think?”

That was when I broke down and sobbed, helplessly, against her. There was no hope for either of us, I knew that. But that it should come like this, with Marjorie speaking as calmly of a knife to kill us both as she would have asked if her embroidery-threads were the right color—that I could not bear, that was beyond all endurance.

When at last I had quieted a little, I rose from her side, going to the door, I said aloud, “We will lock it from the inside this time. Death, at least, is a private affair.” I drew the bolt. I had no hope that it would hold for long when they came for us, but by that time we would no longer care.

I came back to the bed, hauled off the boots I had found myself putting on for some unknown purpose. I knelt before Marjorie, drawing off her light sandals. I drew the clasps from her hair, laid her in my bed.

I thought I had left the Comyn. And now I was dying in order to leave Darkover in the hands of the Comyn, the only hands that could safeguard our world. I drew Marjorie for a moment into my arms.

I was ready to die. But could I force myself to kill her?

“You must,” she whispered, “or you know what they will make me do. And what the Terrans will do to all our people after that.”

She had never looked so beautiful to me. Her bright flame-colored hair was streaming over her shoulders, faintly edged with light. She broke down then, sobbing. I held her against me, straining her so tightly in my arms I must have been hurting her terribly. She held me with all her strength and whispered, “It’s the only way, Lew. The only way. But I didn’t want to die, Lew, I wanted to live with you, to go with you to the lowlands, I wanted … I wanted to have your children.”

I knew no pain in my life, nothing that would ever equal the agony of that moment, with Marjorie sobbing in my arms, saying she wanted to have my children. I was glad I would not live long to remember this; I hoped the dead did not remember …

Our deaths were all that stood between our world and terrible destruction. I took up the knife. Touching my finger to the edge left a stain of blood, and I was insanely glad to feel its razor sharpness.

I bent down to give her a long, last kiss on the lips. I said in a whisper, “I’ll try not to … to hurt you, my darling … ” She closed her eyes and smiled and whispered, “I’m not afraid.”

I paused a moment to steady my hand so that I could do it in a single, swift, painless stroke. I could see the small vein throbbing at the base of her throat. In a few moments we would both be at peace. Then let Kadarin do his worst …

A spasm of horror convulsed me. When we were dead, the last vestige of control was gone from the matrix. Kadarin would die, of course, in the fires of Sharra. But the fires would never die. Sharra, roused and ravening, would rage on, consume our people, our world, all of Darkover …

What would we care for that? The dead are at peace!

And for a painless death for ourselves, would we let our world be destroyed in the fires of Sharra?

The dagger dropped from my hand. It lay on the sheets beside us, but for me it was as far away as if it were on one of the moons. I regretted bitterly that I could not give Marjorie, at least, that swift and painless death. She had suffered enough. It was right that I should live long enough to expiate my treason in suffering. It was cruel, unfair, to make Marjorie share that suffering. Yet, without her Keeper’s training, I would not live long enough to do what I must.

She opened her eyes and said tremulously, “Don’t wait, Lew. Do it now.”

Slowly, I shook my head.

“We cannot take such an easy way, beloved. Oh, we will die. But we must useour deaths. We must close the gateway into Sharra before we die and destroy the matrix if we can. We have to go into it. There’s no chance—you know there’s no chance at all—that we will live through it. But there isa chance that we will live long enough to close the gateway and save our world from being ravaged by Sharra’s fire.”

She lay looking at me, her eyes wide with shock and dread. She said in a whisper, “I would rather die.”

“So would I,” I said, “but such an easy way is not for us, my precious.”

We had sacrificed that right. I looked with longing at the little dagger and its razor sharpness. Slowly, Marjorie nodded in agreement. She picked up the little dagger, looked at it regretfully, then rose from the bed, went to the window and flung it through the narrow window-slit. She came back, slipped down beside me. She said, trying to steady her voice, “Now I cannot lose my courage again.” Then, though her eyes were still wet, her voice held just a hint of the old laughter. “At least we will spend one night together in a proper bed.”