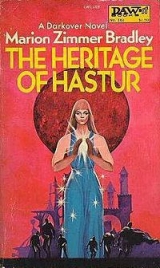

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

“Dani?” Regis said at last, and the boy, startled, dropped the apple and stumbled over his rake as he turned. Regis wondered what to say.

Danilo took a step toward him. “What do youwant?”

“I was on the road to my sister’s house; I stopped to pay my respects to your father and to see how you did.”

He saw Danilo visibly struggling between the impulse to fling the polite gesture back into his face—what more had he to lose?—and the lifelong habit of hospitality. At last he said, “My house and I are at your service, Lord Regis.” His politeness was exaggerated almost to a caricature. “What is my lord’s will?”

Regis said, “I want to talk to you.”

“As you see, my lord, I am very much occupied. But I am entirely at your bidding.”

Regis ignored the irony and took him at his word.

“Come here, then, and sit down,” he said, taking his seat on a fallen log, felled so long ago that it was covered with gray lichen. Silently Danilo obeyed, keeping as far away as the dimensions of the log allowed.

Regis said after a moment, “I want you to know one thing: I have no idea why you were thrown out of the Guards, or rather, I only know what I heard that day. But from the way everyone acted, you’d think I left you to take the blame for something I myself did. Why? What did I do?”

“You know—” Danilo broke off, kicking a windfall apple with the point of his clog. It broke with a rotten, slushy clunk. “It’s over. Whatever I did to offend you, I’ve paid.”

Then for a moment the rapport, the awareness Danilo had wakened in him, flared again between them. He could feel Danilo’s despair and grief as if it were his own. He said, harsh with the pain of it, “Danilo Syrtis, speak your grudge and let me avow or deny it! I tried not to think ill of you even in disgrace! But you called me foul names when I meant you nothing but kindness, and if you have spread lies about me or my kinsmen, then you deserve everything they have done to you, and you still have a score to settle with me!” Without realizing it, he had sprung to his feet, his hand going to the hilt of his sword.

Danilo stood defiant. His gray eyes, gleaming like molten metal beneath dark brows, blazed with anger and sorrow. “ DomRegis, I beg you, leave me in peace! Isn’t it enough that I am here, my hopes gone, my father shamed forever—I might as well be dead!” he cried out desperately, his words tumbling over themselves. “Grudge, Regis? No, no, none against you, you showed me nothing but kindness, but you were one of them, one of those, those—” He stopped again, his voice tight with the effort not to cry. At last he cried out passionately, “Regis Hastur, as the Gods live, my conscience is clear and your Lord of Light and the God of the cristoforosmay judge between the Sons of Hastur and me!”

Almost without volition, Regis drew his sword. Danilo, startled, took a step backward in fear; then he straightened and stiffened his mouth. “Do you punish blasphemy so quickly, lord? I am unarmed, but if my offense merits death, then kill me now where I stand! My life is no good to me!”

Shocked, Regis lowered the point of the sword. “Kill you, Dani?” he said in horror. “God forbid! It never crossed my mind! I wished … Dani, lay your hand on the hilt of my sword.”

Confused, startled into obedience, Danilo put a tentative hand on the hilt Regis gripped hand and hilt together in his own fingers.

“Son of Hastur who is the Son of Aldones who is the Lord of Light! May this hand and this sword pierce my heart and my honor, Danilo, if I had part or knowledge in your disgrace, or if anything you say now shall be used to work you harm!” Again, from the hand-touch, he felt that odd little shock running up his arm, blurring his own thoughts, felt Danilo’s sobs tight in his own throat.

Danilo said on a drawn breath, “No Hastur would forswear that oath!”

“No Hastur would forswear his naked word,” Regis retorted proudly, “but if it took an oath to convince you, an oath you have.” He sheathed the sword.

“Now tell me what happened, Dani. Was the charge a lie, then?”

Danilo was still visibly dazed. “The night I came in—it had been raining. You woke, you knew—”

“I knew only that you were in pain, Dani. No more. I asked if I could help, but you drove me away.” The pain and shock he had felt that night returned to him in full force and he felt his heart pounding again with the agony of it, as he had done when Danilo thrust him away.

Danilo said, “You are a telepath. I thought—”

“A very rudimentary one, Danilo,” said Regis, trying to steady his voice. “I sensed only that you were unhappy, in pain. I didn’t know why and you would not tell me.”

“Why should you care?”

Regis put out his hand, slowly closed it around Danilo’s wrist. “I am Hastur and Comyn. It touches the honor of my clan and my caste that anyone should have cause to speak ill of us. With false slanders we can deal, but with truth, we can only try to right the wrong. We Comyn can be mistaken.” Dimly, at the back of his mind, he realized he had said “We Comyn” for the first time. “More,” he said, and smiled fleetingly, “I like your father, Dani. He was willing to anger a Hastur in order to have you left in peace.”

Danilo stood nervously locking and unlocking his hands. He said, “The charge is true. I drew my dagger on Lord Dyan. I only wish I had cut his throat while I was about it; whatever they did to me, the world would be a cleaner place.”

Regis stared, disbelieving. “ Zandru!Dani—”

“I know, in days past, the men who touched Comyn lord in irreverence would have been torn on hooks. In those days, perhaps, Comyn were worth reverence—”

“Leave that,” Regis said sharply. “Dani, I am heir to Hastur, but even I could not draw steel on an officer without disgrace. Even if the officer I struck were no Comyn lord but young Hjalmar, whose mother is a harlot of the streets.”

Danilo stood fighting for control. “If I struck young Hjalmar, Regis, then I would have deserved my punishment; he is an honorable man. It was not as my officer I drew on Lord Dyan. He had forfeited all claim to obedience or respect.”

“Is that for you to judge?”

“In those circumstances … ” Danilo swallowed. “Could I respect and obey a man who had so far forgotten himself as to try to make me his—” He used a cahuengaword Regis did not know, only that it was unspeakably obscene. But he was still in rapport with Danilo, so there was no scrap of doubt about his meaning. Regis went white. He literally could not speak under the shock of it.

“At first I thought he was joking,” Danilo said, almost stammering. “I do not like such jests—I am a cristoforo—but I gave him some similar joke for an answer and thought that was the end of it, for if he meant the jest in seriousness, then I had given him his answer without offense. Then he made himself clearer and grew angry when I answered him no, and swore he could force me to it. I don’t know what he did to me, Regis, he did something with his mind, so that wherever I was, alone or with others, I felthim touching me, heard his … his foul whispers, that awful, mocking laugh of his. He pursued me, he seemed to be inside my mind all the time. All the time. I thought he meant to drive me out of my mind! I had thought … a telepath could not inflict pain … I can’t stand it even to be aroundanyone who’s really unhappy, but he took some awful, hateful kind of pleasure in it.” Danilo sobbed suddenly. “I went to him, then, I begged him to let me be! Regis, I am no gutter-brat, my family has served the Hasturs honorably for years, but if I were a whore’s foundling and he the king on his throne, he would have had no right to use me so shamefully!” Danilo broke down again and sobbed. “And then … and then he said I knew perfectly well how I could be free of him. He laughedat me, that awful, hideous laugh. And then I had my dagger out, I hardly know how I came to draw it, or what I meant to do with it, kill myself maybe … ” Danilo put his hands over his face. “You know the rest,” he said through them.

Regis could hardly draw breath. “Zandru send him scorpion whips! Dani, why didn’t you lay a charge and claim immunity? He is subject to the laws of Comyn too, and a telepath who misuses his laranthat way … ”

Danilo gave a weary little shrug. It said more than words.

Regis felt wholly numbed by the revelation. How could he ever face Dyan again, knowing this?

I knew it wasn’t true what they said of you, Regis. But you were Comyn too, and Dyan showed you so much favor, and that last night, when you touched me, I was afraid…

Regis looked up, outraged, then realized Danilo had not spoken at all. They were deeply in rapport; he felt the other boy’s thoughts. He sat back down on the log, feeling that his legs were unable to hold him upright.

“I touched you … only to quiet you.” he said at last.

“I know that now. What good would it do to say I am sorry for that, Regis? It was a shameful thing to say.”

“It is no wonder you cannot believe in honor or decency from my kin. But it is for us to prove it to you. All the more since you are one of us. Danilo, how long have you had laran?

“I? Laran? I, Lord Regis?”

“Didn’t you know? How long have you been able to read thoughts?”

“That? Why, all my life, it seems. Since I was twelve or so. Is that… ”

“Don’t you know what it means, if you have one of the Comyn gifts? You do, you know. Telepaths aren’t uncommon, but you opened up my own gift, even after Lew Alton failed.” With a flood of emotion, he thought, you brought me my heritage. “I think you’re what they call a catalyst telepath. That’s very rare and a precious gift.” He forebore to say it was an Ardais gift. He doubted if Danilo would appreciate that information just now. “Have you told anyone else?”

“How could I, when I didn’t know myself? I thought everyone could read thoughts.”

“No, it’s rarer than that. It means you too are Comyn, Dani.”

“Are you saying my parentage is—”

“Zandru’s hells, no! But your family is noble, it may well be that your mother had Comyn kinsmen, Comyn blood, even generations ago. With full laran, though, it means you yourself are eligible for Comyn Council, that you should be trained to use these gifts, sealed to Comyn.” He saw revulsion on Danilo’s face and said quickly, “Think. It means you are Lord Dyan’s equal. He can be held accountable for having misused you,” Regis blessed the impulse that had brought him here. Alone, his mind burdened with the brooding, hypersensitive nature of the untrained telepath, under his father’s grim displeasure … Danilo might have killed himself after all.

“I won’t, though,” Danilo said aloud. Regis realized they had slid into rapport again. He reached out to touch Danilo, remembered and didn’t. To conceal the move he bent and picked up a windfall apple. Danilo got to his feet and began putting on his shirt. Regis finished the apple and dropped the core into a pile of mulch.

“Dani, I am expected to sleep tonight at my sister’s house. But I give my word: you shall be vindicated. Meanwhile, is there anything else I can do for you?”

“Yes, Regis! Yes! Tell my father the disgrace and dishonor were not mine! He asked no questions and spoke no word of reproach, but no man in our family has ever been dishonored. I can bear anything but his belief that I lied to him!”

“I promise you he shall know the full—no.” Regis broke off suddenly. “Isn’t that why you dared not tell him yourself? He would kill—” He saw that he had, in truth, reached the heart of Danilo’s fear.

“He would challenge Dyan,” Danilo said haltingly, “and though he looks strong he is an old man and his heart is far from sound. If he knew the truth—I wantedto tell him everything, but I would rather have him … despise me … than ruin himself.”

“Well, I shall try to clear your name with your father without endangering him. But for yourself, Dani? We owe you something for the injury.”

“You owe me nothing, Regis. If my name is clean before my kinsmen, I am content.”

“Still, the honor of Comyn demands we right this injustice. If there is rot at our heart, well, it must be cleansed.” At this moment, filled with righteous anger, he was ready to fling himself against a whole regiment of unjust men who abused their powers. If the older men in Comyn were corrupt or power-mad, and the younger ones idle, then boys would have to set it right!

Danilo dropped to one knee. He held out his hands, his voice breaking. “There is a life between us. My brother died to shield your father. As for me, I ask no more than to give my life in the service of Hastur. Take my sword and my oath, Lord Regis. By the hand I place on your sword, I pledge my life.”

Startled, deeply moved, Regis drew his sword again, held out the hilt to Danilo. Their hands met on the hilt again as Regis, stumbling on the ritual words, trying to recall them one by one, said, “Danilo-Felix Syrtis, be from this day paxman and shield-arm to me … and this sword strike me if I be not just lord and shield to you … ” He bit his lip, fighting to remember what came next. Finally he said, “The Gods witness it, and the holy things at Hali.” It seemed there was something else, but at least their intention was clear, he thought. He slid the sword back into its sheath, raised Danilo to his feet and shyly kissed him on either cheek. He saw tears on Danilo’s eyelids and knew that his own were not wholly dry.

He said, trying to lighten the moment, “Now you’ve only had formally what we both knew all along, bredu.” He heard himself say the word with a little shock of amazement, but knew he meant it as he had never meant anything before.

Danilo said, trying to steady his voice, “I should have … offered you my sword. I’m not wearing one, but here—”

That was what had been missing in the ritual. Regis started to say that it did not matter, but without it there was something wanting. He looked at the dagger Danilo held out hilt-first to him. Regis drew his own, laid it hilt-to-blade along the other before giving it to Danilo, saying quietly, “Bear this, then, in my service.”

Danilo laid his lips to the blade for a moment, saying, “In your service alone I bear it,” and put it into his own sheath.

Regis thrust Danilo’s knife into the scabbard at his waist. It did not quite fit, but it would do. He said, “You must remain here until I send for you. It will not be long, I promise, but I have to think what to do.”

He did not say goodbye. It was not necessary. He turned and walked back along the lane. As he went into the barn to untie his horse, DomFelix came slowly toward him.

“Lord Regis, may I offer you some refreshment?”

Regis said pleasantly, “I thank you, but grudged hospitality has a bitter taste. Yet it is my pleasure to assure you, on the word of a Hastur”—he touched his hand briefly to sword-hilt—“you may be proud of your son, DomFelix. His dishonor should be your pride.”

The old man frowned. “You speak riddles, vai dom.”

“Sir, you were hawk-master to my grandsire, yet I have not seen you at court in my lifetime. To Danilo a choice even more bitter was given: to win favor by dishonorable means, or to keep his own honor at the price of apparent disgrace. In brief, sir, your son offended the pride of a man who has power but none of the honor which gives power its dignity. And this man revenged himself.”

The old man’s brow furrowed as he slowly puzzled out what Regis was saying. “If the charge was unjust, an act of private revenge, why did my son not tell me?”

“Because, DomFelix, Dani feared you would ruin yourself to avenge him.” He added quickly, seeing a thousand questions forming in the old man’s eyes, “I promised Danilo I would tell you no more than this. But will you accept the word of a Hastur that he is blameless?”

Light broke in the troubled face. “I bless you for coming and I beg you to pardon my rough words, Lord Regis. I am no courtier. But I am grateful.”

“And loyal to your son,” Regis said. “Have no doubt, DomFelix, he is worthy of it.”

“Will you not honor my house, Lord Regis?” This time the offer was heartfelt, and Regis smiled. “I regret that I cannot, sir, I am expected elsewhere. Danilo has shown me your hospitality; you grow the finest apples I have tasted in a long time. And I give you my word that one day it shall be my pleasure to show honor to the father of my friend. Meanwhile, I beg you to be reconciled to your son.”

“You may be sure of it, Lord Regis.” He stood staring after Regis as the boy mounted and rode away, and Regis could sense his confusion and gratitude. As he rode slowly down the hill to rejoin his bodyguard, he realized what he had, in substance, pledged himself to do: to restore Danilo’s good name and make certain that Dyan could not again misuse power this way. What it meant was that he, who had once sworn to renounce the Comyn, now had to reform it from inside out, single-handedly, before he could enjoy his own freedom.

previous | Table of Contents | next

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter TWELVE

(Lew Alton’s narrative)

The hills rise beyond the Kadarin, leading away into the mountains, into the unknown country where the law of the Comyn does not run. In my present state, as soon as I had forded the Kadarin I felt that a weight had been lifted from my shoulders.

In this part of the world, five days’ ride north of Thendara, my safe-conducts meant nothing. We slept at night in tents, with a watch set. It was a barren country, long deserted. Only perhaps three or four times in a day’s ride did we see some small village, half a dozen poor houses clustered in a clearing, or some small-holding where a hardy farmer wrested a bare living from the stony and perpendicular forest. There were so few travelers here that the children came out to watch us as we passed.

The roads got worse and worse as we went further into the hills, degenerating at times into mere goat-tracks and trails. There are not many good roads on Darkover. My father, who lived on Terra for many years, has told me about the good roads there, but added that there was no way to bring that system here. For roads you needed slave labor or immense numbers of men willing to work for the barest subsistence, or else heavy machinery. And there have never been slaves on Darkover, not even slaves to machinery.

It was, I thought, small wonder that the Terrans were reluctant to move their spaceport into these hills again.

I was the more surprised when, on the ninth day of traveling, we came on to a wide road, well-surfaced and capable of handling wheeled carts and several men riding abreast. My father had also told me that when he last visited the hills near Aldaran, Caer Donn had been little more than a substantial village. Reports had reached him that it was now a good-sized city. But this did not diminish my astonishment when, coming to the top of one of the higher hills, we saw it spread out below us in the valley and along the lower slopes of the next mountain.

It was a clear day, and we could see a long distance. Deep in the lowest part of the valley, where the ground was most even, there was a great fenced-in area, abnormally smooth-surfaced, and even from here I could see the runways and the landing strips. This, I thought, must be the old Terran spaceport, now converted to a landing field for their aircraft and the small rockets which brought messages from Thendara and Port Chicago. There was a similar small landing field near Arilinn. Beyond the airfield lay the city, and as my escort drew to a halt behind me, I heard the men murmuring about it.

“There was no city here when I was a lad! How could it grow so fast?”

“It’s like the city which grew up overnight in the old fairytale!”

I told them a little of what Father had said, about prefabricated construction. Such cities were not built to stand for ages, but could be quickly constructed. They scowled skeptically and one of them said, “I’d hate to be rude about the Commander, sir, but he must have been telling you fairy tales. Even on Terra human hands can’t build so quick.”

I laughed. “He also told me of a hot planet where the natives did not believe there was such a thing as snow, and accused him of tale-telling when he spoke of mountains which bore ice all year.”

Another pointed. “Castle Aldaran?”

There was nothing else it could have been, unless we were unimaginably astray: an ancient keep, a fortress of craggy weathered stone. This was the stronghold of the renegade Domain, exiled centuries ago from Comyn—no man alive now knew why. Yet they were the ancient Seventh Domain, of the ancient kin of Hastur and Cassilda.

I felt curiously mingled eagerness and reluctance, as if taking some irrevocable step. Once again the curiously unfocused time-sense of the Altons thrust fingers of dread at me. What was waiting for me in that old stone fortress lying at the far end of the valley of Caer Donn?

With a scowl I brought myself back to the present. It needed no great precognition to sense that in a completely strange part of the world I might meet strangers and that some of them would have a lasting effect on my life. I told myself that crossing that valley, stepping through the gates of Castle Aldaran, was notsome great and irrevocable division in my life which would cut me off from my past and all my kindred. I was here at my father’s bidding, an obedient son, disloyal only in thought and will.

I struggled to get myself back in focus, “Well, we might as well try to reach it while we still have some daylight,” I said, and started down the excellent road.

The ride across Caer Donn was in a strange way dreamlike. I had chosen to travel simply, without the complicated escort of an ambassador, treating this as the family visit it purported to be, and I attracted no particular attention. In a way the city was like myself, I thought, outwardly all Darkovan, but with a subliminal difference somewhere, something that did not quite belong. For all these years I had been content to accept myself as Darkovan; now, looking at the old Terran port as I had never looked at the familiar one at Thendara, I thought that this too was my heritage … if I had courage to take it

I was in a curious mood, feeling a trifle fey, as if, without knowing what shape or form it would take, I could smell a wind that bore my fate.

There were guards at the gates of Aldaran, mountain men, and for the first time I gave my full name, not the one I bore as my father’s nedestroheir, but the name given before either father or mother had cause to suspect anyone could doubt my legitimacy. “I am Lewis-Kennard Lanart-Montray Alton y Aldaran, son of Kennard, Lord Alton, and Elaine Montray-Aldaran. I have come as envoy of my father, and I ask a kinsman’s welcome of Kermiac, Lord Aldaran.”

The guards bowed and one of them, some kind of majordomo or steward, said, “Enter, dom, you are welcome and you honor the house of Aldaran. In his name I extend you welcome, until you hear it from his own lips.” My escort was taken away to be housed elsewhere while I was led to a spacious room high in one of the far wings of the castle; my saddle bags were brought and servants sent to me when they found I traveled with no valet. In general they established me in luxury. After a while the steward returned.

“My lord, Kermiac of Aldaran is at dinner and asks, if you are not too weary from travel, that you join him in the hall. If you are trail-wearied, he bids you dine here and rest well, but he bade me say he was eager to welcome his sister’s grandson.”

I said I would join him with pleasure. At that moment I was not capable of feeling fatigue; the fey mood of excitement was still on me. I washed off the dust of travel and dressed in my best, a fine tunic of crimson-dyed leather with breeches to match, low velvet boots, a dress cape lined with fur—not vanity, this, but to show honor to my unknown kinsman.

Dusk was falling when the servant returned to conduct me to the great dining hall. Expecting dim torchlight, I was struck amazed by the daylight flood of brilliance. Arc-light, I thought, blinking, arc-light such as the Terrans use in their Trade City. It seemed strange to go at night into a room flooded by such noonday brilliance, strange and disorienting, yet I was glad, for it allowed me to see clearly the faces in the great hall. Evidently, despite his use of the newfangled lights, Kermiac kept to the old ways, for the lower part of his hall was crammed with a motley conglomeration of faces, Guardsmen, servants, mountain people, rich and poor, even some Terrans and a cristoforomonk or two in their drab robes.

The servant led me toward the high table at the far end where the nobles sat. At first they were only a blur of faces: a tall man, lean and wolfish, with a great shock of fair hair; a pretty, red-haired girl in a blue dress; a small boy about Marius’ age; and at their center, an aging man with a dark reddish beard, old to decrepitude but still straight-backed and keen-eyed. He bent his eyes on me, studying my face intently. This, I knew, must be Kermiac, Lord Aldaran, my kinsman. He wore plain clothes, of a simple cut like those the Terrans wore, and I felt briefly ashamed of my barbarian finery.

He rose and came down from the dais to greet me. His voice, thinned with age, was still strong.

“Welcome, kinsman.” He held out his arms and gave me a kinsman’s embrace, his thin dry lips pressing each of my cheeks in turn. He held my shoulders between his hands for a moment. “It warms my heart to see your face at last, Elaine’s son. We hear tidings in the Hellers here, even of the Hali’imyn,” He used the ancient mountain word, but without offense. “Come, you must be weary and hungry after this long journey. I am glad you felt able to join us. Come and sit beside me, nephew.”

He led me to a place of honor at his side. Servants brought us food. In the Domains the choicest food is served a guest without asking his preference, so that he need not in courtesy choose the simplest; here they made much of asking whether I would have meat, game-bird or fish, whether I would drink the white mountain wine or the red wine of the valleys. It was all cooked well and served to perfection, and I did it justice after days of trail food.

“So, nephew,” he said at last, when I had appeased my hunger and was sipping a glass of white wine and nibbling at some strange and delicious sweets, “I have heard you are tower-trained, a telepath. Here in the mountains it’s believed that men tower-trained are half eunuch, but I can see you are a man; you have the look of a soldier. Are you one of their Guardsmen?”

“I have been a captain for three years.”

He nodded. “There is peace in the mountains now, although the Dry-Towners get ideas now and then. Yet I can respect a soldier; in my youth I had to keep Caer Donn by force of arms.”

I said, “In the Domains it is not known that Caer Donn is so great a city.”

He shrugged. “Largely of Terran building. They are good neighbors, or we find them so. Is it otherwise in Thendara?”

I was not yet ready to discuss my feelings about the Terrans, but to my relief he did not pursue that topic. He was studying my face in profile.

“You are not much like your father, nephew. Yet I see nothing of Elaine in you, either.”

“It is my brother Marius who is said to have my mother’s face and her eyes.”

“I have never seen him. I last saw your father twelve years ago, when he brought Elaine’s body here to rest among her kin. I asked then for the privilege of fostering her sons, but Kennard chose to rear you in his own house.”

I had never known that. I had been told nothing of my mother’s people. I was not even sure what degree of kin I was to the old man, I said something of this to him, and he nodded.

“Kennard has had no easy life,” Kermiac said. “I cannot blame him that he never wanted to look back. But if he chose to tell you nothing of your mother’s kin, he cannot take offense that I tell you now in my own fashion. Years ago, when the Terrans were mostly stationed at Caer Donn and the ground had just been broken for the fine building at Thendara—I hear it has been finished in this winter past—years ago, then, when I was not much more than a boy, my sister Mariel chose to marry a Terran, Wade Montray. She dwelt with him many years on Terra. I have heard the marriage was not a happy one and they separated, after she had borne him two children. Mariel chose to remain with her daughter Elaine on Terra; Wade Montray came with his son Larry, whom we called Lerrys, back to Darkover. And now you may see how the hand of fate works, for Larry Montray and your father, Kennard, met as boys and swore friendship. I am no great believer in predestination or a fate foretold, but so it came about that Larry Montray remained on Darkover to be fostered at Armida and your father was sent back to Terra, to be fostered as Wade Montray’s son, in the hope that these two lads would build again the old bridge between Terra and Darkover. And there, of course, your father met Montray’s daughter, who was also the daughter of my sister Mariel. Well, to make a long tale short, Kennard returned to Darkover, was given in marriage to a woman of the Domains, who bore him no child, served in Arilinn Tower—some of this you must have been told. But he bore the memory of Elaine, it seems, ever in his heart, and at last sought her in marriage. As her nearest kinsman, it was I who gave consent. I have always felt such marriages are fortunate, and children of mixed blood the closest road to friendship between people of different world. I had no idea, then, that your Comyn kinsmen would not bless the marriage as I had done, and rejoice in it.”

All the more wrong of the Comyn, I thought, since it was by their doing that my father had first gone to Terra. Well, it was all of a piece with their doings since. And another score I bore against them.

Yet my father stood with them!

Kenniac concluded, “When it was clear they would not accept you, I offered to Kennard that you should be fostered here, honored at least as Elaine’s son if not as his. He was certain he could force them, at last, to accept you. He must have succeeded, then?”