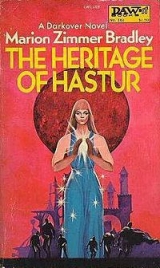

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter FIFTEEN

For ten days the storm had raged, sweeping down from the Hellers through the Kilghard Hills and falling on Thendara with fury almost unabated. Now the weather was clear and fine, but Regis rode with his head down, ignoring the bright day.

He’d failed, he felt, having made a pledge and then doing nothing. Now he was being packed off to Neskaya in Gabriel’s care, like a sick child with a nanny! But he raised his head in surprise as they made the sharp turn that led down the valley toward Syrtis.

“Why are we taking this road?”

“I have a message for DomFelix,” Gabriel said. “Will the few extra miles weary you? I can send you on to Edelweiss with the Guards … ”

Gabriel’s careful solicitude set him on edge. As if a few extra miles could matter! He said so, irritably.

His black mare, sure-footed, picked her way down the path. Despite his disclaimer to Gabriel, he felt sick and faint, as he had felt most of the time since his collapse in Kennard’s rooms. For a day or two, delirious and kept drugged, he had had no awareness of what was going on, and even now much of what he remembered from the last few days was illusion. Danilo was there, crying out in wild protest, being roughly handled, afraid, in pain. It seemed that Lew was there sometimes too, looking cold and stern and angry with him, demanding again and again, What is it that you’re afraid to know?He knew, because they told him afterward, that for a day or two he had been so dangerously ill that his grandfather never left his side, and when, waking once between sick intervals of fragmented hallucinations, he had seen his grandfather’s face and asked, “Why are you not at Council?” the old man had said violently, “Damn the Council!” Or was that another dream? He knew that once Dyan had come into the room, but Regis had hidden his face in the bedclothes and refused to speak to him, gently though Dyan spoke. Or was that a dream, too? And then, for what seemed like years, he had been on the fire-lines at Armida, when they had lived day and night with terror; during the day the hard manual work kept it at bay, but at night he would wake, sobbing and crying out with fear … That night, his grandfather told him, his half-conscious cries had grown so terrified, so insistent, that Kennard Alton, himself seriously ill, had come and stayed with him till morning, trying to quiet him with touch and rapport. But he kept crying out for Lew and Kennard couldn’t reach him.

Regis, ashamed of this childish behavior, had finally agreed to go to Neskaya. The blur of memory and thought-images embarrassed him, and he didn’t try to sort out the truth from the drugged fantasies. Just the same, he knew that at least once Lew had been there, holding him in his arms like the frightened child he had been. When he told Kennard so, Kennard nodded soberly and said, “It’s very likely. Perhaps you were astray in time; or perhaps from where he is, Lew sensed that you had need for him, and reached you as a telepath can. I had never known you were so close to him.” Regis felt helpless, vulnerable, so when he was well enough to ride, he had meekly agreed to go to Neskaya Tower. It was intolerable to live like this …

Gabriel’s voice roused him now, saying in dismay, “Look! What’s this? DomFelix—”

The old man was riding up the valley toward them, astride Danilo’s black horse, the Armida-bred gelding which was the only really good horse at Syrtis. He was coming at what was, for a man his age, a breakneck pace. For a few minutes it seemed he would ride full tilt into the party on the path, but just a few paces away he pulled up the black and the animal stood stiff-legged, breathing hard, its sides heaving.

DomFelix glared straight at Regis. “Where is my son? What have you thieving murderers done with him?”

The old man’s fury and grief were like a blow. Regis said in confusion, “Your son? Danilo, sir? Why do you ask me?”

“What have you vicious, detestable tyrants done with him? How dare you show your faces on my land, after stealing from me my youngest—”

Regis tried to interrupt and quell the torrent of words. “ DomFelix, I do not understand. I parted from Danilo some days ago, in your own orchard. I have not laid eyes on him since; I have been ill—” The memory of his drugged dream tormented him, of Danilo being roughly handled, afraid, in pain …

“Liar!” DomFelix shouted, his face red and ugly with rage and pain. “Who but you—”

“That’s enough, sir,” said Gabriel, breaking in with firm authority. “No one speaks like that to the heir to Hastur. I give you my word—”

“The word of a Hastur lickspittle and toady! Idare speak against these filthy tyrants! Did you take my son for your—” He flung a word at Regis next to which “catamite” was a courtly compliment. Regis paled against the old man’s rage.

“ DomFelix—if you will hear me—”

“Hear you! My son heard you, sir, all your fine words!”

Two Guardsmen rode close to the enraged old man, grasping the reins of his horse, holding him motionless.

“Let him go,” Gabriel said quietly. “ DomFelix, we know nothing of your son. I came to you with a message from Kennard Alton concerning him. May I deliver it?”

DomFelix quieted himself with an effort that made his eyes bulge. “Speak, then, Captain Lanart, and the Gods deal with you as you Comyn dealt with my son.”

“The Gods do so to me and more also, if I or mine harmed him,” Gabriel said. “Hear the message of Kennard, Lord Alton, Commander of the Guard: ‘Say to DomFelix of Syrtis that it is known to me what a grave miscarriage of justice was done in the Guards this year, of which his son Danilo-Felix, cadet, may have been an innocent victim; and ask that he send his son Danilo-Felix to Thendara under any escort of his own choosing, to stand witness in a full investigation against men in high places, even within Comyn, who may have misused their powers.’ ” Gabriel paused, then added, “I was also authorized to say to you, DomFelix, that ten days from now, when I have escorted my brother-in-law, who is in poor health at this moment, to Neskaya Tower, that I shall myself return and escort your son to Thendara, and that you are yourself welcome to accompany him as his protector, or to name any guardian or relative of your own choosing, and that Kennard Alton will stand personally responsible for his safety and honor.”

DomFelix said unsteadily, “I have never had reason to doubt Lord Alton’s honor or goodwill. Then Danilo is not in Thendara?”

One of the Guards, a grizzled veteran, said, “You know me, sir, I served with Rafael in the war, sixteen years gone. I kept an eye on young Dani for his sake. I give you my word, sir, Dani isn’t there, with Comyn conniving or without it.”

The old man’s face gradually paled to its normal hue. He said, “Then Danilo did not run away to join you, Lord Regis?”

“On my honor, sir, he did not. I saw him last when we parted in your own orchard. Tell me, how did he go, did he leave no word?”

The old man’s face was clay-colored. “I saw nothing. Dani had been hunting; I was not well and had kept my bed. I said to him I had a fancy for some birds for supper, the Gods forgive me, and he took a hawk and went for them, such a good obedient son—” His voice broke. “It grew late and he did not return. I had begun to wonder if his horse had gone lame, or he’d gone on some boy’s prank, and then old Mauris and the kitchen-folk came running into my chamber and told me, they saw him meet with riders on the path and saw him struck down and carried away … ”

Gabriel looked puzzled and dismayed. “On my word, DomFelix, none of us had art, part or knowledge of it What hour was this? Yesterday? The day before?”

“The day before, Captain. I swooned away at the news. But as soon as my old bones would bear me I took horse to come and hold … someone to account … ” His voice faded again. Regis drew his own horse close to DomFelix and took his arm. He said impulsively, “Uncle,” using the same word he used to Kennard Alton, “you are father to my friend; I owe you a son’s duty as well. Gabriel, take the Guards, go and look, question the house-folk.” He turned back to DomFelix, saying gently, “I swear I will do all I can to bring Danilo safely back. But you are not well enough to ride. Come with me.” Taking the other’s reins in his own hands, he turned the old man’s mount and led him down the path into the cobbled courtyard. Dismounting quickly, he helped DomFelix down and guided his tottering steps. He led him into the hall, saying to the old half-blind servant there, “Your master is ill, fetch him some wine.”

When it had been brought and DomFelix had drunk a little, Regis sat beside him, near the cold hearth.

“Lord Regis, your pardon … ”

“None needed. You have been sorely tried, sir.”

“Rafael … ”

“Sir, as my father held your elder son dear, I tell you Danilo’s safety and honor are as dear to me as my own.” He looked up as the Guardsmen came into the hall. “What news, Gabriel?”

“We looked over the ground where he was taken. The ground was trampled and he had laid about him with his dagger.”

“Hawking, he had no other weapon.”

“They cut off sheath and all.” Gabriel handed DomFelix the weapon. He drew it forth a little way, saw the Hastur crest on it. He said, “Dom Regis—”

“We swore an oath,” said Regis, drawing Danilo’s dagger from his own sheath where he wore it, “and exchanged blades, in token of it.” He took the dagger with the Hastur crest, saying, “I will bear this to restore to him. Did you see anything else, Gabriel?”

One of the Guardsmen said, “I found this on the ground, torn off in the fight. He must have fought valiantly for a young lad outnumbered.” He held out a long, heavy cloak of thick colorless wool, bound with leather buckles and straps. It was much cut and slashed. DomFelix sat up a little and said, “That fashion of cloak has not been worn in the Domains in my lifetime; I believe they wear them still in the Hellers. And it is lined with marl-fur; it came from somewhere beyond the river. Mountain bandits wore such cloaks. But why Dani? We are not rich enough to ransom him, nor important enough to make him valuable as a hostage.”

Regis thought grimly that Dyan’s men came from the Hellers. Aloud he said only, “Mountain men act for whoever pays them well. Have you enemies, DomFelix?”

“No. I have dwelt in peace, farming my acres, for fifteen years.” The old man sounded stunned. He looked at Regis and said, “My lord, if you are sick—”

“No matter,” Regis said. “ DomFelix, I pledge you by the oath no Hastur may break that I shall find out who has done this to you, and restore Dani to you, or my own life stand for it.” He laid his hand over the old man’s for a moment. Then he straightened and said, “One of the Guardsmen shall remain here, to look after your lands in your son’s absence. Gabriel, you ride back with the escort to Thendara and carry this news to Kennard Alton. And show him this cloak; he may know where in the Hellers it was woven.”

“Regis, I have orders to take you to Neskaya.”

“In good time. This must come first,” Regis said. “You are a Hastur, Gabriel, if only by marriage-right, and your sons are Hastur heirs. The honor of Hastur is your honor, too, and Danilo is my sworn man.”

His brother-in-law looked at him, visibly wavering. There were good things about being heir to a Domain, Regis decided like having your orders obeyed without question. He said impatiently, “I shall remain here to bear my friend’s father company, or wait at Edelweiss.”

“You cannot stay here unguarded,” Gabriel said at last. “Unlike Dani, you are rich enough for ransom, and important enough for a hostage.” He stood near enough to Comyn to be undecided. “I should send a Guardsman with you to Edelweiss,” he said. Regis protested angrily. “I am not a child! Must I have a nanny trotting at my heels to ride three miles?”

Gabriel’s own older sons were beginning to chafe at the necessity of being guarded night and day. Finally Gabriel said, “Regis, look at me. You were placed in my care. Pledge me your word of honor to ride directly to Edelweiss, without turning aside from your road unless you meet armed men, and you may ride alone.”

Regis promised and, taking his leave of DomFelix, rode away. As he rode toward Edelweiss, he thought, a little triumphantly, that he had actually outwitted Gabriel. A more experienced officer would have allowed him, perhaps, to ride to Edelweiss on his promise to go directly … but he would also have made Regis give his pledge not to depart from there without leave!

His triumph was short-lived. The knowledge of what he must do was tormenting him. He had to find out where—and how—Danilo was taken. And there was only one way to do that: his matrix. He had never touched the jewel since the ill-fated experiment with kirian. It was still in the insulated bag around his neck. The memory of that twisting sickness when he looked into Lew’s matrix was still alive in him, and he was horribly afraid.

Surprisingly for these peaceful times, the gates of Edelweiss were shut and barred, and he wondered what alarm had sealed them. Fortunately most of Javanne’s servants knew his voice, and after a moment Javanne came running down from the house, a servant-woman puffing at her heels. “Regis! We had word that armed men had been seen in the hills! Where is Gabriel?”

He took her hands. “Gabriel is well, and on his way to Thendara. Yes, armed men were seen at Syrtis, but I think it was a private feud, not war, little sister.”

She said shakily, “I remember so well the day Father rode to war! I was a child then, and you not born. And then word came that he was dead, with so many men, and the shock killed Mother … ”

Javanne’s two older sons came racing toward them, Rafael and Gabriel, nine years old and seven, dark-haired, well-grown boys. They stopped short at the sight of Regis and Rafael said, “I thought you were sick and going to Neskaya. What are you doing here, kinsman?”

Gabriel said, “Mother said there would be war. Is there going to be war, Regis?”

“No, as far as I know, there is no war here or anywhere, and you be thankful for it,” Regis said. “Go away now, I must talk with your mother.”

“May I ride Melisande down to the stables?” Gabriel begged, and Regis lifted the child into the saddle and went up to the house with Javanne.

“You have been ill; you are thinner,” Javanne said. “I had word from Grandfather you were on your way to Neskaya. Why are you here instead?”

He glanced at the darkening sky. “Later, sister, when the boys are abed and we can talk privately. I’ve been riding all the day; let me rest a little and think. I’ll tell you everything then.”

Left alone, he paced his room for a long time, trying to steel himself to what he knew he must do.

He touched the small bag around his neck, started to draw it out, then thrust it back, unopened. Not yet.

He found Javanne before the fire in her small sitting room; she had just finished nursing the smaller of the twins and was ready for dinner. “Take the baby to the nursery, Shani,” she told the nurse, “and tell the women I’m not to be disturbed for any reason. My brother and I will dine privately.”

“ Su serva, domna,” the woman said, took the baby and went away. Javanne came and served Regis herself. “Now tell me, brother. What happened?”

“Armed men have taken Danilo Syrtis from his home.”

She looked puzzled. “Why? And why should you disturb yourself about it?”

“He is my paxman; we have sworn the oath of bredin,” Regis said, “and it may well be private revenge. This is what I must find out.” He gave her such an edited version of the affair in the cadet corps as he thought fit for a woman’s ears. She looked sick and shocked. “I have heard of Dyan’s … preferences, who has not? At one time there was talk he should marry me. I was glad when he refused, although I, of course, was offered no choice in the matter. He seems to me a sinister man, even cruel, but I had not thought him criminal as well. He is Comyn, and oath-bound never to meddle with the integrity of a mind. You think he took Dani, to silence him?”

“I cannot accuse him without proof,” Regis said. “Javanne, you spent time in a tower. How much training have you?”

“I spent one season there,” she said. “I can use a matrix, but they said I had no great talent for it, and Grandfather said I must marry young.”

He drew out his own matrix and said, “Can you show me how to use it?”

“Yes, no great skill is needed for that. But not as safely as they can at Neskaya, and you are not yet wholly well. I would rather not.”

“I must know now, at once, what has come to Danilo. The honor of our house is engaged, sister.” He explained why. She sat with her plate pushed aside, twirling a fork. At last she said “Wait” and turned away from him, fumbling at the throat of her gown. When she turned back there was something silk-wrapped in her hands. She spoke slowly, the troubled frown still on her features. “I have never seen Danilo. But when I was a little maiden, and old DomFelix was the hawk-master, I knew DomRafael well; he was Father’s bodyguard and they went everywhere together. He used to call me pet names and take me up on his saddle and give me rides … I was in love with him, as a little girl can be with any handsome man who is kind and gentle to her. Oh, I was not yet ten years old, but when word came that he had been killed, I think I wept more for him than I did for Father. I remember once I asked him why he had no wife and he kissed my cheek and said he was waiting for me to grow up to be a woman.” Her cheeks were flushed, her eyes far away. At last she sighed and said, “Have you any token of Danilo, Regis?”

Regis took the dagger with the Hastur crest. He said, “We both swore on this, and it was cut from his belt when he was taken.”

“Then it should resonate to him,” she said, taking it in her hands and laying it lightly against her cheekbone. Then, the dagger resting in her palm, she uncovered the matrix. Regis averted his eyes, but not before he got a glimpse of a blinding blue flash that wrenched at his gut. Javanne was silent for a moment, then said in a faraway voice, “Yes, on the hillside path, four men—strange cloaks—an emblem, two eagles—cut away his dagger, sheath and all– Regis! He was taken away in a Terran helicopter!” She raised her eyes from the matrix and looked at him in amazement.

Regis’ heart felt as if a fist were squeezing it. He said, “Not to Thendara; the Terrans there would have no use for him. Aldaran!”

Her voice was shaking. “Yes. The ensign of Aldaran is an eagle, doubled … and they would find it easy to beg or borrow Terran aircraft—Grandfather has done it here in urgency. But why?”

The answer was clear enough. Danilo was a catalyst telepath. There had been a time when Kermiac of Aldaran trained Keepers in his mountains, and no doubt there were ways he could still use a catalyst.

Regis said in a low voice, “He has already borne more than any untrained telepath was meant to bear. If further strain or coercion is put on him his mind may snap. I should have brought him back with me to Thendara instead of leaving him there unguarded. This is my fault.”

Bleakly, struggling against a horrible fear, he raised his head. “I must rescue him. I am sworn. Javanne, you must help me key into the matrix. I have no time to go to Neskaya.”

“Regis, is there no other way?”

“None. Grandfather, Kennard, the council—Dani is nothing to them. If it had been Dyan they might have exerted themselves. If Aldaran’s men had kidnapped me, they’d have an army on the road! But Danilo? What do you think?”

Javanne said, “That nedestroheir of Kennard’s. He was sent to Aldaran and he’s kin to them. I wonder if he had a hand in this.”

“Lew? He wouldn’t.”

Javanne looked skeptical. “In your eyes he can do no wrong. As a little boy you were in love with him as I with DomRafael; I have no child’s passion for him, to blind me to what he is. Kennard forced him on Council with ugly tricks.”

“You have no right to say so, Javanne. He is sealed to Comyn and tower-trained!”

She refused to argue. “In any case, I can see why you feel you must go, but you have no training, and it is dangerous. Is there such need for haste?” She looked into his eyes and said after a moment, “As you will. Show me your matrix.”

His teeth clenched, Regis unwrapped the stone. He drew breath, astonished: faint light glimmered in the depths of the matrix. She nodded. “I can help you key it, then. Without that light, you would not be ready. I’ll stay in touch with you. It won’t do much good, but if you … go out and can’t get back to your body, it could help me reach you.” She drew a deep breath. For an instant then he felt her touch. She had not moved, her head was lowered over the blue jewel so that he saw only the parting in her smooth dark hair, but it seemed to Regis that she bent over him, a slim childish girl still much taller than he. She swung him up, as if he were a tiny child, astride her hip, holding him loosely on her arm. He had not thought of this in years, how she had done this when he was very little. She walked back and forth, back and forth, along the high-arched hall with the blue windows, singing to him in her husky low voice … He shook his head to clear it of the illusion. She still sat with her head bent over the matrix, an adult again, but her touch was still on him, close, protective, sheltering. For a moment he felt that he would cry and cling to her as he had done then.

Javanne said gently, “Look into the matrix. Don’t be afraid, this one isn’t keyed to anyone else; mine hurt you because you’re out of phase with it. Look into it, bend your thoughts on it, don’t move until you see the lights waken inside it … ”

He tried deliberately to relax; he realized that he was tensing every muscle against remembered pain. He finally looked into the pale jewel, feeling only a tiny shock of awareness, but something inside the jewel glimmered faintly. He bent his thoughts on it, reached out, reached out … deep, deep inside. Something stirred, trembled, flared into a living spark.

Then it was as if he had blown his breath on a coal from the fireplace: the spark was brilliant blue fire, moving, pulsing with the very rhythm of his blood. Excitement crawled in him, an almost sexual thrill.

“Enough!” Javanne said. “Look away quickly or you’ll be trapped!”

No, not yet … Reluctantly, he wrenched his eyes from the stone. She said, “Start slowly. Look into it only a few minutes at a time until you can master it or it will master you. The most important lesson is that you must always control it, never let it control you.”

He gave it a last glance, wrapped it again with a sense of curious regret, feeling Javanne’s protective touch/embrace withdraw. She said, “You can do with it what you will, but that is not much, untrained. Be careful. You are not yet immune to threshold sickness and it may return. Can a few days matter so much? Neskaya is only a little more than a day’s ride away.”

“I don’t know how to explain, but I feel that every moment matters. I’m afraid Javanne, afraid for Danilo, afraid for all of us. I must go now, tonight. Can you find me some old riding-clothes of Gabriel’s, Javanne? These will attract too much attention in the mountains. And will you have your women make me some food for a few days? I want to avoid towns nearby where I might be recognized.”

“I’ll do it myself; no need for the women to see and gossip.” She left him to his neglected supper while she went to find the clothing. He did not feel hungry, but dutifully stowed away a slice of roast fowl and some bread. When she came back, she had his saddlebags, and an old suit of Gabriel’s. She left him by the fire to put them on, then he followed her down the hall to a deserted kitchen. The servants were long gone to bed. She moved around, making up a package of dried meat, hard bread and crackers, dried fruit She put a small cooking-kit into the saddlebags, saying it was one which Gabriel carried on hunting trips. He watched her silently, feeling closer to this little-known sister than he had felt since he was six years old and she left their home to marry. He wished he were still young enough to cling to her skirts as he had then. An ice-cold fear gripped at him, and then the thought: before going into danger, a Comyn heir must himself leave an heir. He had refused even to think of it, as Dyan had refused, not wanting to be merely a link in a chain, the son of his father, the father of his sons. Something inside him rebelled, deeply and strongly, at what he must do—Why bother? If he did not return, it would all be the same, one of Javanne’s sons named his heir … He could do nothing, say nothing …

He sighed. It was too late for that, he had gone too far. He said, “One thing more, sister. I go where I may never return. You know what that means. You must give me one of your sons, Javanne, for my heir.”

Her face blanched and she gave a low, stricken cry. He felt the pain in it but he did not look away, and finally she said, her voice wavering, “Is there no other way?”

He tried to make it a feeble joke. “I have no time to get one in the usual way, sister, even if I could find some woman to help me at such short notice.”

Her laughter was almost hysterical; it cut off in the middle, leaving stark silence. He saw slow acceptance dawning in her eyes. He had known she would agree. She was Hastur, of a family older than royalty. She had of necessity married beneath her, since there was no equal, and she had come to love her husband deeply, but her duty to the Hasturs came first. She only said, her voice no more than a thread, “What shall I say to Gabriel?”

“He has known since the day he took you to wife that this day might come,” Regis said. “I might well have died before coming to manhood.”

“Come, then, and choose for yourself.” She led the way to the room where her three sons slept in cots side by side. By the candlelight Regis studied their faces, one by one. Rafael, slight and dark, close-cropped curls tousled around his face; Gabriel, sturdy and swarthy and already taller than his brother. Mikhail, who was four, was still pixie-small, fairer than the others, his rosy cheeks framed in light waving locks, almost silvery white. Grandfather must have looked like that as a child, Regis thought. He felt curiously cold and bereft. Javanne had given their clan three sons and two daughters. He might never father a son of his own. He shivered at the implications of what he was doing, bent his head, groping through an unaccustomed prayer. “Cassilda, blessed Mother of the Domains, help me choose wisely … ”

He moved quietly from cot to cot. Rafael was most like him, he thought. Then, on some irresistible impulse, he bent over Mikhail, lifted the small sleeping form in his arms.

“This is my son, Javanne.”

She nodded, but her eyes were fierce. “And if you do not return he will be Hastur of Hastur; but if you doreturn, what then? A poor relation at the footstool of Hastur?”

Regis said quietly, “If I do not return, he will be nedestro, sister. I will not pledge you never to take a wife, even in return for this great gift. But this I swear to you: he shall come second only to my first legitimately born son. My second son shall be third to him, and I will take oath no other nedestroheir shall ever displace him. Will this content you, breda?”

Mikhail opened his eyes and stared about him sleepily, but he saw his mother and did not cry. Javanne touched the blond head gently, “It will content me, brother.”

Holding the child awkwardly in unpracticed arms, Regis carried him out of the room where his brothers slept. “Bring witnesses,” he said, “I must be gone soon. You know this is irrevocable, Javanne, that once I take this oath, he is not yours but mine, and must be sealed my heir. You must send him to Grandfather at Thendara.”

She nodded. Her throat moved as she swallowed hard, but she did not protest “Go down to the chapel,” she said. “I will bring witnesses.”

It was an old room in the depths of the house, the four old god-forms painted crudely on the walls, lights burning before them. Regis held Mikhail on his lap, letting the child sleepily twist a button on his tunic, until the witnesses came, four old men and two old women of the household. One of the women had been Javanne’s nurse in childhood, and his own.

He took his place solemnly at the altar, Mikhail in his arms.

“I swear before Aldones, Lord of Light and my divine forefather, that Hastur of Hastur is this child by unbroken blood line, known to me in true descent. And in default of any heir of my body, therefore do I, Regis-Rafael Felix Alar Hastur y Elhalyn, choose and name him my nedestroheir and swear that none save my first-born son in true marriage shall ever displace him as my heir; and that so long as I live, none shall challenge his right to my hearth, my home or my heritage. Thus I take oath in the presence of witnesses known to us both. I declare that my son shall be no more called Mikhail Regis Lanart-Hastur, but—” He paused, hesitating among old Comyn names for suitable new names which would confirm the ritual. There was no time to search the rolls for names of honor. He would commemorate, then, the desperate need which had driven him to this. “I name him Danilo,” he said at last. “He shall be called Danilo Lanart Hastur, and I will so maintain to all challenge, facing my father before me and my sons to follow me, my ancestry and my posterity. And this claim may never be renounced by me while I live, nor in my name by any of the heirs of my body.” He bent and kissed his son on the soft baby lips. It was done. They had a strange beginning. He wondered what the end would be. He turned his eyes on his old nurse.

“Foster-mother, I place you in charge of my son. When the roads are safe, you must take him to the Lord Hastur at Thendara, and see to it that he is given the Sign of Comyn.”

Javanne was dropping slow tears, but she said nothing except, “Let me kiss him once more,” and allowed the old woman to carry the child away. Regis followed them with his eyes. His son. It was a strange feeling. He wondered if he had laranor the unknown Hastur gift; he wondered if he would ever know, would ever see the child again.