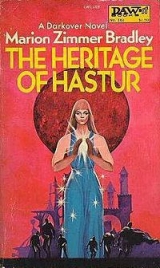

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter THREE

Regis ran down the corridor, dazed and confused, the small points of color still flashing behind his eyes, racked with the interior crawling nausea. One thought was tearing at him:

Failed. I’ve failed. Even Lew, tower-trained and with all his skill, couldn’t help me. There’s nothing there. When he said what he did about potential, he was humoring me, comforting a child.

He reeled, feeling sick again, clung momentarily to the wall and ran on.

The Comyn castle was a labyrinth, and Regis had not been inside it in years. Before long, in his wild rush to get away from the scene of his humiliation, he was well and truly lost. His senses, kirian-blurred, retained vague memories of stone cul-de-sacs, blind corners, archways, endless stairs up which he toiled and down which he blundered and sometimes fell, courtyards filled with rushing wind and blinding rain, hour after hour. To the end of his life he retained an impression of the Comyn Castle which he could summon at will to overlay his real memories of it: a vast stone maze, a trap through which he wandered alone for centuries, with no human form to be seen. Once, around a corner, he heard Lew calling his name. He flattened himself in a niche and hid for a few thousand years until, long after, the sound was gone.

After an indeterminate time of wandering and stumbling and hallucinating, he became aware that it had been a long time since he had fallen down a flight of stairs; that the corridors were long, but not miles and miles long; and that they were no longer filled with uncanny crawling colors and silent sounds. When he came out at last on to a high balcony at the uppermost level, he knew where he was.

Dawn was breaking over the city below him. Once before, during the night, he had stood against a high parapet like this, thinking that his life was no good to anyone, not to the Hasturs, not to himself, that he should throw himself down and be done with it This time the thought was remote, nightmarish, like one of those terrible real dreams which wakes you shaking and crying out, but a few seconds later is gone in dissolving fragments.

He drew a long, weary sigh. Now what?

He should go and make himself presentable for his grandfather, who would certainly send for him soon. He should get some food and sleep; kirian, he’d been told, expended so much physical and nervous energy that it was essential to compensate with extra food and rest He should go back and apologize to Lew Alton, who had only very reluctantly done what Regis himself had begged him to do … But he was sick to death of hearing what he should do!

He looked across the city that lay spread out below him, Thendara, the old town, the Trade City, the Terran headquarters and the spaceport. And the great ships, waiting, ready to take off for some unguessable destination. All he really wanted to do now was go to the spaceport and watch, at close range, one of those great ships.

Quickly he hardened his resolve. He was not dressed for out-of-doors at all, still wearing felt-soled indoor boots, but in his present mood it mattered less than nothing. He was unarmed. So what? Terrans carried no sidearms. He went down long flights of stairs, losing his way, but knowing, now that he had his wits about him, that all he had to do was keep going down till he reached ground level. Comyn Castle was no fortress. Built for ceremony rather than defense, the building had many gates, and it was easy to slip out one of them unobserved.

He found himself in a dim, dawnlit street leading downhill through closely packed houses. He was keyed up, having had no sleep after his hard ride yesterday, but the energizing effect of the kirianhad not worn off yet, and he felt no drowsiness. Hunger was something else, but there were coins in his pockets, and he was sure that soon he would pass some kind of eating-house where workmen ate before their day’s business.

The thought excited him with a delicious forbiddenness. He could not remember ever having been completely alone in his entire life. There had always been others ready at hand to look after him, protect him, gratify his every wish: nurses and nannies when he was small, servants and carefully selected companions when he was older. Later, there were the brothers of the monastery, though they were more likely to thwart his wishes than carry them out. This would be an adventure.

He found a place next to a blacksmith’s shop and went in. It was dimly lit with resin-candles, but there was a good smell of food. He was briefly afraid of being recognized, but after all, what could they do to him? He was old enough to be out alone. Besides, if anyone noticed the blue-and-silver cloak with the Hastur badge, they would only think he was a Hastur servant.

The men seated at the table were blacksmiths and stable hands, drinking hot ale or jacoor boiled milk, eating foods Regis had never seen or smelled. A woman came to take Regis’ order. She did not look at him. He ordered fried nut porridge and hot milk with spices in it. His grandfather, he thought with definite satisfaction, would have a fit.

He paid for the food and ate it slowly, at first feeling the residual queasiness of the drug which wore off as he ate. When he went out, feeling better, the light was spreading, although the sun had not risen. As he went downhill he found himself among unfamiliar houses, built in strange shapes of strange materials. He had obviously crossed the line into the Trade City. He could hear, in the distance, that strange waterfall sound which had excited him so intensely. He must be near the spaceport.

He had been told a little about the spaceport on Darkover. Darkover, which did almost no trading with the Empire, was in a unique location, between the upper and lower spiral arms of the galaxy, unusually well suited as a crossroads stop for much of the interstellar traffic. In spite of the self-chosen isolation of Darkover, therefore, enormous numbers of ships came for rerouting, bearing passengers, personnel and freight bound elsewhere. They also came for repairs and reprovisioning and for rest leaves in the Trade City. Most of the Terrans scrupulously kept the agreement limiting them to their own areas. There had been a few intermarriages, a little trade, some small—very small—importation of Terran machinery and technology. This was strictly limited by the Darkovans, each item studied by Council before permission was given. A few licensed matrix technicians were set up in the cities; a few had even gone out into the Empire. The Terrans, he had heard, were intrigued by Darkovan matrix technology and in the old days had laid intricate plots to uncover some of its secrets. He didn’t know details, but Kennard had told him some stories.

He started, realizing that the street directly before him was blocked by two very large men in unfamiliar black leather uniforms. At their belts hung strangely shaped weapons which, Regis realized with a prickle of horror, must be blasters or nerve guns. Such weapons had been outlawed on Darkover since the Ages of Chaos, and Regis had literally never seen one before, except for antiques in a museum. These were no museum pieces. They looked deadly.

One of the men said, “You’re violating curfew, sonny. Until the trouble’s over, all women and children are supposed to be off the streets from an hour before sunset until an hour after sunrise.”

Women and children! Regis’ hand strayed to his knife-hilt. “I am no child. Shall I call challenge and prove it?”

“You’re in the Terran Zone, son. Save yourself trouble.”

“I demand—”

“Oh hell, one of those,” said the second man in disgust “Look here, kiddie, we’re not allowed to fight duels, on duty anyhow. You come along and talk to the officer.”

Regis was about to make an angry protest—ask a Comyn heir to give an account of himself in Council season?—when it occurred to him that the headquarters building was right on the spaceport, where he was going anyway. With a secret grin he went along.

After they had passed through the spaceport gates, he realized that he had actually had a better view yesterday from the mountainside. Here the ships were invisible behind fences and barricades. The spaceforce patrolmen led him inside a building where a young officer, not in black leather but in ordinary Terran clothing, was dealing with assorted curfew violators. As they came in he was saying, “This man’s all right; he was looking for a midwife and took the wrong turn. Send someone to show him back to the town.” He looked up at Regis, standing between the officers. “Another one? I’d hoped we’d be through for the night. Well, kid, what’s your story?”

Regis threw his head back arrogantly. “Who are you? By what right did you have me brought here?”

“My name’s Dan Lawton,” the man said. He spoke the same language in which Regis had addressed him, and spoke it well. That wasn’t common. He said, “I am an assistant to the Legate and just now I’m handling curfew duty. Which you were violating, young man.”

One of the spaceforce men said, “We brought him straight to you, Dan. He wanted to fight a duel with us, for God’s sake! Can you handle this one?”

“We don’t fight duels in the Terran Zone,” Lawton said. “Are you new to Thendara? The curfew regulations are posted everywhere. If you can’t read, I suggest you ask someone to read them to you.”

Regis retorted, “I recognize no laws but those of the Children of Hastur!”

A strange look passed over Lawton’s face. Regis thought for a moment that the young Terran was laughing at him, but face and voice were alike noncommittal. “A praiseworthy objective, sir, but not particularly suitable here. The Hasturs themselves made and recognized those boundaries and agreed to assist us in enforcing our laws within them. Do you refuse to recognize the authority of Comyn Council? Who are you to refuse?”

Regis drew himself to his full height. He knew that between the giant spaceforce men he still looked childishly small.

“I am Regis-Rafael Felix Alar Hastur y Elhalyn,” he stated proudly.

Lawton’s eyes reflected amazement. “Then what, in the name of all your own gods, are you doing roaming around alone at this hour? Where is your escort? Yes, you look like a Hastur,” he said as he pulled an intercom toward him, speaking urgently in Terran Standard. Regis had learned it at Nevarsin. “Have the Comyn Elders left yet?” He listened a moment, then turned back to Regis. “A dozen of your kin-folk left here about half an hour ago. Were you sent with a message for them? If so, you came too late.”

“No,” Regis confessed, “I came on my own. I simply had a fancy to see the starships take off.” It sounded, here in this office, like a childish whim. Lawton looked startled.

“That’s easily enough arranged. If you’d sent in a formal request a few days ago, we’d gladly have arranged a tour for any of your kinsmen. At short notice like this, there’s nothing spectacular going on, but there’s a cargo transport about to take off for Vega in a few minutes, and I’ll take you up to one of the viewing platforms. Meanwhile, could I offer you some coffee?” He hesitated, then said, “You couldn’t be Lord Hastur; that must be your father?”

“Grandfather. For me the proper address is Lord Regis.” He accepted the proffered Terran drink, finding it bitter but rather pleasant. Dan Lawton led him into a tall shaft which rose upward at alarming speed, opening on a glass-enclosed viewing terrace. Below him an enormous cargo ship was in the final stages of readying for takeoff, with refueling cranes being moved away, scaffoldings and loading platforms being wheeled like toys to a distance. The process was quick and efficient. He heard again the waterfall sound, rising to a roar, a scream. The great ship lifted slowly, then more swiftly and finally was gone … out, beyond the stars.

Regis remained motionless, staring at the spot in the sky where the starship had vanished. He knew there were tears in his eyes again but he didn’t care. After a little while Lawton guided him down the elevator shaft. Regis went as if sleepwalking. Resolve had suddenly crystallized inside him.

Somewhere in the Empire, somewhere away from the Domains which had no place for him, there must be a world for him. A world where he could be free of the tremendous burden laid on the Comyn, a world where he could be himself, more than simply heir to his Domain, his life laid out in preordained duties from birth to grave. The Domain? Let Javanne’s sons have it! He felt almost intoxicated by the smell of freedom. Freedom from a burden he’d been born to—and born unfit to bear!

Lawton had not noticed his preoccupation. He said, “I’ll arrange an escort for you back to Comyn Castle, Lord Regis. You can’t go alone, put it out of your mind. Impossible.”

“I came here alone, and I’m not a child.”

“Certainly not,” Lawton said, straight-faced, “but with the situation in the city now, anything might happen. And if an accident occurred, I would be personally responsible.”

He had used the castaphrase implying personal honor. Regis lifted his eyebrows and congratulated him on his command of the language.

“As a matter of fact, Lord Regis, it is my native tongue. My mother never spoke anything else to me. It was Terran I learned as a foreign language.”

“You are Darkovan?”

“My mother was, and kin to Comyn. Lord Ardais is my mother’s cousin, though I doubt he’d care to acknowledge the relationship.”

Regis thought about that as Lawton arranged his escort. Relatives far more distant than that were often seated in Comyn Council. This Terran officer—half-Terran—might have chosen to be Darkovan. He had as much right to a Comyn seat as Lew Alton, for instance. Lew could have chosen to be Terran, as Regis was about to choose his own future. He spent the uneventful journey across the city thinking how he would break the news to his grandfather.

In the Hastur apartments, a servant told him that Danvan Hastur was awaiting him. As he changed his clothes—the thought of presenting himself before the Regent of Comyn in house clothes and felt slippers was not even to be contemplated—he wondered grimly if Lew had said anything to his grandfather. It occurred to him, hours too late, that if anything had happened to him, Hastur might well have held Lew responsible. A poor return for Lew’s friendship!

When he had made himself presentable, in a sky-blue dyed-leather tunic and high boots, he went up to his grandfather’s audience room.

Inside he found Danvan Hastur of Hastur, Regent of the Seven Domains, talking to Kennard Alton. As he opened the door, Hastur raised his eyebrows and gestured to him to sit down. “One moment, my lad, I’ll talk to you later.” He turned back to Kennard and said in a tone of endless patience, “Kennard, my friend, my dear kinsman, what you ask is simply impossible. I let you force Lew on us—”

“Have you regretted it?” Kennard demanded angrily. “They tell me at Arilinn that he is a strong telepath, one of their best. In the Guard he is a competent officer. What right have you to assume Marius would bring disgrace on the Comyn?”

“Who spoke of disgrace, kinsman?” Hastur was standing before his writing table, a strongly built old man, not as tall as Kennard, with hair that had once been silver-gilt and was now nearly all gray. He spoke with a slow, considered mildness. “I let you force Lew on us and I’ve had no reason to regret it. But there is more to it than that. Lew does not look Comyn, no more than you, but there is no question in anyone’s mind that he is Darkovan and your son. But Marius? Impossible.”

Kennard’s mouth thinned and tightened. “Are you questioning the paternity of an acknowledged Alton son?” Standing quietly in a corner, Regis was glad Kennard’s rage was not turned on him.

“By no means. But he has his mother’s blood, his mother’s face, his mother’s eyes. My friend, you know what the first-year cadets go through in the Guards … ”

“He’s my son and no coward. Why do you think he would be incompetent to take his place, the place to which he is legally entitled—”

“Legally, no. I won’t quibble with you, Ken, but we never recognized your marriage to Elaine. Marius is legally, as regards inheritance and Domain-right, entitled to nothing whatever. We gaveLew that right. Not by birth entitlement, but by Council action, because he was Alton, telepath, with full laran. Marius has received no such rights from Council.” He sighed. “How can I make you understand? I’m sure the boy is brave, trustworthy, honest—that he has all the virtues we Comyn demand of our sons. Any lad you reared would have those qualities. Who knows better than I? But Marius looks Terran. The other lads would tear him to pieces. I know what Lew went through. I pitied him, even while I admired his courage. They’ve accepted him, after a fashion. They would never accept Marius. Never. Why put him through that misery for nothing?”

Kennard clenched his fists, striding angrily up and down the room. His voice choked with rage, he said, “You mean that I can get a cadet commission for some poor relation, or for my bastard son by a whore or an idiot, sooner than for my own legitimately born younger son!”

“Kennard, if it were up to me, I’d give the lad his chance. But my hands are tied. There has been enough trouble in Council over citizenship for those of mixed blood. Dyan—”

“I know all too well how Dyan feels. He’s made it abundantly clear.”

“Dyan has a great deal of support in Council. And Marius’ mother was not only Terran but half-Aldaran. If you had hunted over Darkover for a generation, you could not have found a woman less likely to be accepted as the mother of your legitimate sons.”

Kennard said in a low voice, “It was your own father who had me sent to Terra, by the will of Council, when I was fourteen years old. Elaine was reared and schooled on Terra, but she thought of herself as Darkovan. I did not even know of her Terran blood at first. But it made no difference. Even had she been all Terran … ” He broke off. “Enough of that It is long past and she is dead. As for me, I think my record and reputation, my years commanding the Guard, my ten years at Arilinn, prove abundantly what I am.” He paced the floor, his uneven step and distraught face betraying the emotion he tried to keep out of his voice. “You are not a telepath, Hastur. It was easy for you to do what your caste required of you. The Gods know I tried to love Caitlin. It wasn’t her fault But I did love Elaine, and she was mother to my sons.”

“Kennard, I’m sorry. I cannot fight the whole Council for Marius, unless—has he laran?”

“I have no idea. Does it matter so much?”

“If he had the Alton gift, it might be possible, not easy but possible, to establish some rights for him. There are precedents. With laran, even a distant kinsman can be adopted into the Domains. Without it … no, Kennard, Don’t ask. Lew is accepted now, even respected. Don’t ask more.”

Kennard said, his head bent, “I didn’t want to test Lew for the Alton gift. Even with all my care, it came near to killing him. Hastur, I cannot risk that again! Would you, for your youngest son?”

“My only son is dead,” Hastur said and sighed. “If I can do anything else for the boy—”

Kennard answered, “The only thing I want for him is his right, and that is the one thing you will not give. I should have taken them both to Terra. You made me feel I was needed here.”

“You are, Ken, and you know it as well as I.” Hastur’s smile was very sweet and troubled. “Some day, perhaps, you may see why I can’t do what you wish.” His eyes moved to Regis, fidgeting on the bench. He said, “If you will excuse me, Kennard … ”

It was a courteous but definite dismissal. Kennard withdrew, but his face was grim and he omitted any formal leave-taking. Hastur looked tired. He sighed and said, “Come here, Regis. Where have you been? Haven’t I trouble enough without worrying that you’ve run away like a silly brat, to look at the spaceships or something like that?”

“The last time I gave you too much trouble, Grandfather, you sent me into a monastery. Isn’t it too bad you can’t do it again, sir?”

“Don’t be insolent, you young pup,” Hastur growled. “Do you want me to apologize for having no welcome last night? Very well, I apologize. It wasn’t my choice.” He came and took Regis in his arms, pressing his withered cheeks one after another to the boy’s. “I’ve been up all night or I’d think of some better way to welcome you now.” He held him off at arm’s length, blinking with weariness. “You’ve grown, child. You are very like your father. He would have been proud, I think, to see you coming home a man.”

Against his own will, Regis was moved. The old man looked so weary. “What crisis kept you up all night, Grandfather?”

Hastur sank down heavily on the bench. “The usual thing. I expect it’s known on every planet where the Empire builds a big spaceport, but we’re not used to it here. People coming and going from all corners of the Empire. Travelers, transients, spacemen on leave and the sector which caters to them. Bars, amusement places, gambling halls, houses of … er … ”

“I’m old enough to know what a brothel is, sir.”

“At your age? Anyway, drunken men are disorderly, and Terrans on leave carry weapons. By agreement, no weapons can be carried into the old city, but people do stray across the line—there’s no way of preventing it, short of building a wall across the city. There have been brawls, duels, knife fights and sometimes even killings, and it isn’t always clear whether the City Guard or the Terran spaceforce should properly handle the offenders. Our codes are so different that it’s hard to know how to compromise. Last night there was a brawl and a Terran knifed one of the Guardsmen. The Terran offered as his defense that the Guardsman had made him what he called an indecent proposition. Must I explain?”

“Of course not. But are you trying to tell me, seriously, that this was offered as a legal defense for murder?”

“Seriously. Evidently the Terrans take it even more seriously than the cristoforos. He insisted his attack on the Guardsman was justifiable. Now the Guardsman’s brother has filed an intent-to-murder on the Terran. The Terrans aren’t subject to our laws, so he refused to accept it and instead filed charges against the Guardsman’s brother for attempted murder. What a tangle! I never thought I’d see the day when Council had to sit on a knife fight! Damn the Terrans anyhow!”

“So how did you finally settle it?”

Hastur shrugged. “Compromise, as usual. The Terran was deported and the Guardsman’s brother was held in the brig until the Terran was off-planet; so nobody gets any peace except the dead man. Unsatisfactory for everyone. But enough of them. Tell me about yourself, Regis.”

“Well, I’ll have to talk about the Terrans again,” Regis said. This wasn’t the best time, but his grandfather might not have time to talk with him again for days. “Grandfather, I’m not needed here. You probably know I don’t have laran, and I found out in Nevarsin that I’m not interested in politics. I’ve decided what I want to do with my life: I want to go into the Terran Empire Space Service.”

Hastur’s jaw dropped. He scowled and demanded, “Is this a joke? Or another silly prank?”

“Neither, Grandfather. I mean it, and I’m of age.”

“But you can’t do that! Certainly they’d never accept you without my consent.”

“I hope to have that, sir. But by Darkovan law, which you were quoting at Kennard, I am of legal age to dispose of myself. I can marry, fight a duel, acknowledge a son, stand responsible for a murder—”

“The Terrans wouldn’t think so. Kennard was declared of age before he went. But on Terra he was sent to school and required, legally forced, mind you, to obey a stipulated guardian until he was past twenty. You’d hate that.”

“No doubt I would. But I learned one thing at Nevarsin, sir—you can live with the things you hate.”

“Regis, is this your revenge for my sending you to Nevarsin? Were you so unhappy? What can I say? I wanted you to have the best education possible and I thought it better for you to be properly cared for, there, than neglected at home.”

“No, sir,” Regis said, not quite sure. “It’s simply that I want to go, and I’m not needed here.”

“You don’t speak Terran languages.”

“I understand Terran Standard. I learned to read and write at Nevarsin. As you pointed out, I am excellently well educated. Learning a new language is no great matter.”

“You say you are of age,” Hastur said coldly, “so let me quote some law back to you. The law provides that before you, who are heir to a Domain, undertake any such risky task as going offworld, you must provide an heir to your Domain. Have you a son, Regis?”

Regis looked sullenly at the floor. Hastur knew, of course, that he had not. “What does that matter? It’s been generations since the Hastur gift has appeared full strength in the line. As for ordinary laran, that’s just as likely to appear at random anywhere in the Domains as it is in the direct male line of descent. Pick any heir at random, he couldn’t be less fit for the Domain than I am. I suspect the gene’s a recessive, bred out, extinct like the catalyst telepath trait. And Javanne has sons; one of them is as likely to have it as any son of mine, if I had any. Which I don’t,” he added rebelliously, “or am likely to. Now or ever.”

“Where do you get these ideas?” Hastur asked, shocked and bewildered. “You’re not, by any chance, an ombredin?”

“In a cristoforomonastery? Not likely. No, sir, not even for pastime. And certainly not as a way of life.”

“Then why should you say such a thing?”

“Because,” Regis burst out angrily, “I belong to myself, not to the Comyn! Better to let the line die with me than to go on for generations, calling ourselves Hastur, without our gift, without laran, political figureheads being used by Terra to keep the people quiet!”

“Is that how you see me, Regis? I took the Regency when Stefan Elhalyn died, because Derik was only five, too young to be crowned even as a puppet king. It’s been my ill-fortune to rule over a period of change, but I think I’ve been more than just a figurehead for Terra.”

“I know some Empire history, sir. The Empire will finally take over here too. It always does.”

“Don’t you think I know that? I’ve lived with the inevitable for three reigns now. But if I live long enough, it will be a slow change, one our people can live with. As for laran, it wakens late in Hastur men. Give yourself time.”

“Time!” Regis put all his dissatisfaction into the word.

“I haven’t laraneither, Regis. But even so, I think I’ve served my people well. Couldn’t you resign yourself to that?” He looked into Regis’ stubborn face and sighed. “Well, I’ll bargain with you. I don’t want you to go as a child, subject to a court-appointed guardian under Terran law. That would disgrace all of us. You’re the age when a Comyn heir should be serving in the cadet corps. Take your regular turn in the Guards, three cadet seasons. After that if you still want to go, we’ll think of a way to get you offworld without going through all the motions of their bureaucracy. You’d hate it—I’ve had fifty years of it and I still hate it But don’t walk out on the Comyn before you give it a fair try. Three years isn’t that long. Will you bargain?”

Three years. It had seemed an eternity at Nevarsin. But did he have a choice? None, except outright defiance. He could run away, seek aid from the Terrans themselves. But if he was legally a child by their laws, they would simply hand him over again to his guardians. That would indeed be a disgrace.

“Three cadet seasons,” he said at last. “But only if you give me your word of honor that if I choose to go, you won’t oppose it after that.”

“If after three years you still want to go,” said Hastur, “I promise to find some honorable way.”

Regis listened, weighing the words for diplomatic evasions and half-truths. But the old man’s eyes were level and the word of Hastur was proverbial. Even the Terrans knew that.

At last he said, “A bargain. Three years in the cadets, for your word.” He added bitterly, “I have no choice, do I?”

“If you wanted a choice,” said Hastur, and his blue eyes flashed fire though his voice was as old and weary as ever, “you should have arranged to be born elsewhere, to other parents. I did not choose to be chief councillor to Stefan Elhalyn, nor Regent to Prince Derik. Rafael—sound may he sleep!—did not choose his own life, nor even his death. None of us has ever been free to choose, not in my lifetime.” His voice wavered, and Regis realized that the old man was on the edge of exhaustion or collapse.

Against his will, Regis was moved again. He bit his lip, knowing that if he spoke he would break down, beg his grandfather’s pardon, promise unconditional obedience. Perhaps it was only the last remnant of the kirian, but he knew, suddenly and agonizingly, that his grandfather did not meet his eyes because the Regent of the Seven Domains could not weep, not even before his own grandson, not even for the memory of his only son’s terrible and untimely death.

When Hastur finally spoke again his voice was hard and crisp, like a man accustomed to dealing with one unremitting crisis after another. “The first call-over of cadets is later this morning. I have sent word to the cadet-master to expect you among them.” He rose and embraced Regis again in dismissal. “I shall see you again soon. At least we are not now separated by three days’ ride and a range of mountains.”

So he’d already sent word to the cadet-master. That was how sure he was, Regis realized. He had been manipulated, neatly mouse-trapped into doing just exactly what was expected of a Hastur. And he had maneuvered himself into promising three years of it!

previous | Table of Contents | next