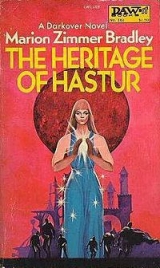

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Can a night last a lifetime?

Perhaps, If you know your lifetime is measured in a single night.

I said hoarsely, drawing her into my arms again, “Let’s not waste any of it.”

Neither of us was strong enough for much physical love-making. Most of that night we spent resting in each other’s arms, sometimes talking a little, more often caressing one another in silence. From long training at disciplining unwelcome or dangerous thoughts, I was able to put away almost completely all thought of what awaited us tomorrow. Strangely enough, my worst regret was not for death, but for the long, quiet years of living together which we would never know, for the poignant knowledge that Marjorie would never know the hills near Armida, that she would never come there as a bride. Toward morning Marjorie cried a little for the child she would not live long enough to bear. Finally, cradled in my arms, she fell into a restless sleep. I lay awake, thinking of my father and of my unborn son, that too-fragile spark of life, barely kindled and already extinguished. I wished Marjorie had been spared that knowledge, at least. No, it was right that someone should weep for it, and I was beyond tears.

Another death to my account …

At last, when the rising sun was already staining the distant peaks with crimson, I slept too. It was like a final grace of some unknown goddess that there were no evil dreams, no nightmares of fire, only a merciful darkness, the dark robe of Avarra covering our sleep.

I woke still clasped in Marjorie’s arms. The room was full of sunlight; her golden eyes were wide, staring at me with fear.

“They will come for us soon,” she said.

I kissed her, slowly, deliberately, before I rose. “So much the less time of waiting,” I said, and went to draw back the bolt. I dressed myself in my best, defiantly digging from my packs my finest silk under-tunic, a jerkin and breeches of gold-colored dyed leather. A Comyn heir did not go to his death like a common criminal being hanged! Some such emotion must have been in Marjorie yesterday, for she had evidently put on her finest gown, pale-blue, woven of spider-silk and cut low across the breasts. Instead of her usual plaits, she coiled her hair high atop her head with a ribbon. She looked beautiful and proud. Keeper, comynara.

Servants brought us some breakfast. I was grateful that she could smile proudly, thanking them in her usual gracious manner. There were no traces in her face of the tears and terror of yesterday; we held our heads high and smiled into each other’s eyes. Neither of us dared speak.

As I had known he would, Kadarin came in as we were silently sharing the last of the fruits on the tray. I did not know how my body could contain such hate. I was physically sick with the lust to kill him, to feel my fingers meeting in the flesh of his throat.

And yet—how can I say this?—there was nothing left there to hate. I looked up just once and quickly looked away. He was not even a man any more, but something else. A demon? Sharra walking like a man? The real man Kadarin was not there any more. Killing him would not stop the thing that used him.

Another score against Sharra: this man had been my friend. The destruction of Sharra would not only kill him, it would avenge him, too.

He said, “Have you managed to make him see sense, Marjorie? Or must I drug him again?”

Her fingertips touched mine out of his sight. I knew he did not see, though he would always have noticed before. I said, “I will do what you ask me.” I could not bring myself to call him Bob or even Kadarin. He was too far from what I had known.

As we walked through the corridors, I looked sidewise at Marjorie. She was very pale; I felt the life in her flaring fitfully. Sharra had drained her, sapped her life-forces nearly to the death. One more reason not to go on living. Strange, I was thinking as if I had a choice.

We stepped out onto the high balcony overlooking Caer Donn and the Terran airfield. On a lower level I saw them all assembled, the faces I had seen in my … what? Dream, drugged nightmare? Or had that part been real? It seemed I knew the faces. Some ragged, some in rich garments, some knowing and sophisticated, some dulled and ignorant, some not even entirely human. But one and all, their eyes gleamed with the same glassy intensity.

Sharra!Their eagerness burned at me, tearing, ravaging.

I looked down at Caer Donn. My breath stuck in my throat. Marjorie had told me, but no words could have prepared me for this kind of destruction, ruin, desolation.

Only after the great forest fire that had ravaged the Kilghard Hills near Armida had I seen anything like this. The city lay blackened; for wide areas not one stone remained upon another. All the old city lay blasted, wasted, the damage spreading far into the Terran Zone.

And I had played a part in this!

I had thought I knew how dangerous the great matrices could be. Looking down on this wasteland which had been a beautiful city, I knew I had never known anything at all. And all these deaths were on my single account. I could never expiate or atone. But perhaps, perhaps, I might live long enough to end the damage.

Beltran stood on the heights. He looked like death. Rafe was nowhere to be seen. I did not think Kadarin would have hesitated to destroy him now, but I hoped, with a deeplying pain, that the boy was alive and safe somewhere well away from this. But I had no hope. If the Sharra matrix was actually smashed, no one who had been sealed into it was likely to live.

Kadarin was unwrapping the long, bundled length of the sword which contained the Sharra matrix. Beyond him I saw Thyra, her eyes burning into mine with an ineradicable hatred. I had hurt her beyond bearing, too. And, unlike Marjorie, she had not even consented to her death. I had loved her, and she would never know.

Kadarin placed the sword in my hand. The matrix, throbbing with power at the junction of hilt and blade, made my burned hand stab blindly with a pain that reached all the way up my arm, made me feel sick. But I must be in physical contact with it, not mental touch alone. I took it from the sword, held it in my hand. I knew my hand would never be usable again after this, but what matter? What did a dead man care for a hand burned from his corpse? I had been trained to endure even such terrible pain, and it could not last long. If I could endure just long enough for what I had to do …

We know what you are trying to do, Lew. Stand firm and we will help.

I felt my whole body twitch. It was my father’s voice!

It was cruel, a stabbing hope. He must be very near or he could never have reached us through the enormous blanking-out field of the Sharra matrix.

Father! Father!It was a great surge of gratitude. Even if we all died, perhaps his strength added to mine could help us live long enough to destroy this thing. I locked firmly with Marjorie, made contact through the Sharra matrix, felt the old rapport flame into life: Kadarin’s enormous sustaining strength, Thyra like a savage beast, giving the linkage claws, savagery, a wild prowling frenzy. And it all flooded through me …

It was not the way we had used it before, the closed circle of power. As I raised the matrix this time I felt a mighty river of energy flooding through Kadarin, the vast floods of raw emotion from the men standing below: worship, rage, anger, lust, hatred, destruction, the savage power of fire, burning, burning …

This was what I had felt before, the dream, the nightmare.

Marjorie was already etched in the aureole of light. Slowly, as the power grew, pouring into my mind through the linked focus, then channeling through me into Marjorie, I saw her begin to change, take on power and height and majesty. The fragile girl in the blue dress merged, moment by moment, into the great looming goddess, arms tossed to the sky, flames shaking exultantly like tossed tresses, a great fountain of flame …

Lew, hold steady for me. I cannot do this without your full cooperation. It will hurt, you know it may kill you, but you know what hangs on this, my son …

My father’s touch, more familiar than his voice. And almost the same words he had spoken before.

I knew perfectly well where I was, standing in the matrix circle of Sharra on the heights of Castle Aldaran, the great form of fire towering over me. Marjorie, her identity lost, dissolved in the fire and yet controlling it like a torch-dancer with her torches in her hands, swooped down to touch the old spaceport with a fingertip of fire. Far below us there was a vast booming explosion; one of the starships shattered like a child’s toy, vanishing skyward in flames. And yet, though all of me was here, now, still I stood again in my father’s room at Armida, waiting, sick with that terrible fear—and elation! I reached for him with a wild and reckless confidence. Go on! Do it! Finish what you started! Better at your hands than Sharra’s!

I felt it then, the deep Alton focused rapport, blazing alive in me, spreading into every corner of my brain and being, filling my veins. It was such agony as I had never known, the fierce, violent traumatic tearingrapport, a ripping open of every last fiber of my brain. Yet this time I was in control. I was the focus of all this power and I reached out, twisting it like a steel rope in my hand, a blazing rope of fire. The hand was searing with flame but I barely felt it. Kadarin was motionless, arched backward, accepting the stream of emotions from the men below, transforming them into energons, focusing them through me and into Sharra. Marjorie … Marjorie was there somewhere in the midst of the great fire, but I could see her face, confident, unafraid, laughing. I looked at her for a brief instant, wishing in anguish that I could bring her, even for a fraction of a second, out and free from Sharra, see her again—no time. No time for that. I saw the goddess pause to strike. I must act now, quickly, before I too was caught up in that mindless fire, that rage for violence and destruction. I looked for a last instant of anguish and atonement into my father’s loving eyes.

I braced myself against the terrible throbbing agony in the hand that held the matrix. Just a little more. Just a moment more,I spoke to the screaming agony as if it were a separate living entity, you can bear it just an instant more.I focused on the black and wavering darkness behind the form of fire where, instead of the parapets and towers of Castle Aldaran, a blurring darkness grew, out of focus, a monstrous doorway, a gate of fire, a gate of power, where somethinghovered, swayed, bulged as if trying to break through that gateway. I gathered all the power of the focused minds, all of them, my father’s strength, my own, Kadarin’s and all the hundred or so mindless, focused believers behind him pouring out all their raw lust and emotion and strength …

I held all that power, fused like a rope of fire, a twisted cable of force. I focused it all on the matrix in my hand. I smelled burning flesh and knew it was my own hand burning and blackening, as the matrix glowed, flared, flamed, ravened, a fire that filled all the worlds, the gateway between the worlds, the reeling and crashing universes …

I smashed the gateway, pouring all that fire back into it. The form of fire shrank, died, scattered and dimmed. I saw Marjorie, reeling, collapse forward; I leaped to snatch her within the circle of my arm, clinging to the matrix still. I heard her screaming as the fires turned back, flaring, blazing up in her very flesh. I caught her fainting body in my arms and with a final, great thrust of power, hurled myself between space, into the gray world, elsewhere.

Space reeled under me; the world disappeared. In the formless gray spaces we were bodiless, painless. Was this death? Marjorie’s body was still warm in my arms, but she was unconscious. I knew we could remain between worlds only an instant. All the forces of balance tore at me, pulling me back, back to that holocaust and the rain of fire and the ruin at Castle Aldaran, where the men who had spent their powers collapsed and died, blackened and burned, as the fires burned out. Back there, back there to ruin and death? No! No!Some last struggle, some last vitality in me cried out No!and in a great final thrust of focused power, draining myself ruthlessly, I pushed Marjorie and myself through the closing gates and escaped…

My feet struck the floor. It was cool daylight in a curtained, sunlit room; there was hellish pain in my hand, and Marjorie, hanging between my arms, was moaning senselessly. The matrix was still clutched in the blackened, crisped ruin that had been a hand. I knew where I was: in the highest room of the Arilinn Tower, within the safety-field. A girl in the white draperies of a psi-monitor was staring at me, her eyes wide. I knew her; she had been in her first year at Arilinn, my last year there. I gasped “Lori! Quick, the Keeper—”

She vanished from the room and I gratefully let myself fall to the floor, half senseless, next to Marjorie’s moaning body.

We were here at Arilinn. Safe. And alive!

I had never been able to teleport before, but for Marjorie’s sake I had done it.

Consciousness came and went, wavering like a gray curtain. I saw Callina Aillard looking down at me, her gray eyes reflecting pain and pity. She said softly, “I am Keeper here now, Lew. I will do what I can.” Her hand insulated in the gray silk veil, she reached out to take the matrix, thrusting it quickly within the field of a damper. The cessation of the vibration behind the matrix was a moment of almost heavenly comfort, but it also turned off the near-anesthesia of deep focused effort. I had felt hellish pain in my hand before, but now it felt flayed and dipped anew in molten lead. I don’t know how I kept from screaming.

I dragged myself to Marjorie’s side. Her face was contorted, but even as I looked, it went slack and peaceful. She had fainted and I was glad. The fires that had burned my hand to a sickening, charred ruin had struck inward through her, as the fire of Sharra withdrew back through that opened gateway. I dared not let myself think what she must have suffered, what she must still suffer if she lived. I looked up at Callina with terrible appeal and read there what Callina had been too gentle to tell me in words.

Callina knelt beside us, saying with a gentleness I had never heard in any woman’s voice, “We will try to save her for you, Lew.” But I could see the faint, blue-lighted currents of energy pulsing dimmer and dimmer. Callina lifted Marjorie in her arms, kneeling, held her head against her breast. Marjorie’s features flickered for a moment in renewed consciousness and renewed pain; then her eyes blazed into mine, golden, triumphant, proud. She smiled, whispered my name, rested her head peacefully on Callina’s breast and closed her eyes. Callina bent her head, weeping, and her long dark hair fell like a mourning veil across Marjorie’s stilled face.

I let consciousness slip away, let the fire in my hand take my whole body. Maybe I could die too.

But there was not even that much mercy anywhere in the universe.

previous | Table of Contents | next

previous | Table of Contents

Epilogue

The Crystal Chamber, high in Comyn Castle, was the most formal of all the meeting places for Comyn Council. An even blue light spilled through the walls; flashes of green, crimson, violet struck through, reflected from the prisms everywhere in the glass. It was like meeting at the heart of a rainbow, Regis thought, wondering if this was in honor of the Terran Legate. Certainly the Legate looked suitably impressed. Not many Terrans had ever been allowed to see the Crystal Chamber.

“ … in conclusion, my lords, I am prepared to explain to you what provisions have been made for enforcing the Compact on a planet-wide basis,” the Legate said, and Regis waited while the interpreter repeated his words in castafor the benefit of the Comyn and assembled nobles. Regis, who understood Terran Standard and had heard it the first time around, sat thinking about the young interpreter, Dan Lawton, the redheaded half-Darkovan whom he had met at the spaceport.

Lawton could have been on the other side of the railing, listening to this speech, not interpreting it for the Terrans. Regis wondered if he regretted his choice. It was easy enough to guess: no choice ever went wholly unregretted. Regis was mostly thinking of his own.

There was still time. His grandfather had made him promise three years. But he knew that for him, time had run out on his choices.

Dan Lawton was finishing up the Legate’s speech.

“ … every individual landing at any Trade City, whether at Thendara, Port Chicago or Caer Donn, when Caer Donn can be returned to operation as a Trade City, will be required to sign a formal declaration that there is no contraband in his possession, or to leave all such weapons under bond in the Terran Zone. Furthermore, all weapons imported to this planet for legal use by Terrans shall be treated with a small and ineradicable mark of a radioactive substance, so that the whereabouts of such weapons can be traced and they can be recalled.”

Regis gave a faint, wry smile. How quickly the Terrans had come around, when they discovered the Compact was not designed to eliminate Terran weapons but the great and dangerous Darkovan ones. They had had enough of Darkovan ones on the night when Caer Donn burned. Now they were all too eager to honor the Compact, in return for a Darkovan pledge to continue to do so.

So Kadarin accomplished something. And for the Comyn. What irony!

A brief recess was called after the Legate’s speech and Regis, going to stretch his legs in the corridor, met Dan Lawton briefly face to face.

“I didn’t recognize you,” the young Terran said. “I didn’t know you’d taken a seat in Council, Lord Regis.”

Regis said, “I’m anticipating the fact by about half an hour, actually.”

“This doesn’t mean your grandfather is going to retire?”

“Not for a great many years, I hope.”

“I heard a rumor—” Lawton hesitated. “I’m not sure it’s proper to be talking like this outside of diplomatic channels … ”

Regis laughed and said, “Let’s say I’m not tied down to diplomatic channels for half an hour yet. One of the things I hope to see altered between Terran and Darkovan is this business of doing everything through diplomatic channels. It’s your custom, not ours.”

“I’m enough of a Darkovan to resent it sometimes. I heard a rumor that there would be war with Aldaran. Any truth to it?”

“None whatever, I’m glad to say. Beltran has enough trouble. The fire at Caer Donn destroyed nearly eighty years of loyalty to Aldaran among the mountain people—and eighty years of good relations between Aldaran and the Terrans. The last thing he wants is to fight the Domains.”

“Rumor for rumor,” Lawton said. “The man Kadarin seems to have vanished into thin air. He’d been seen in the Dry Towns, but he’s gone again. We’ve had a price on his head since he quit Terran intelligence thirty years ago—”

Regis blinked. He had seen Kadarin only once, but he would have sworn the man was no more than thirty.

“We’re watching the ports, and if he tries to leave Darkover we’ll take him. Personally I’d say good riddance. More likely he’ll hide out in the Hellers for the rest of his natural life. If there’s anything natural about it, that is.”

The recess was over and they began to return to the Crystal Chamber. Regis found himself face to face with Dyan Ardais. Dyan was dressed, not in his Domain colors, but in the drab black of ritual mourning.

“Lord Dyan—no, Lord Ardais, may I express my condolences.”

“They are wasted,” Dyan said briefly. “My father has not been in his right senses for years before you were born, Regis. What mourning I made for him was so long ago I have even forgotten what grief I felt. He has been dead more than half of my life; the burial was unduly delayed, that was all.” Briefly, grimly, he smiled.

“But formality for formality, Lord Regis. My congratulations.” His eyes held a hint of bleak amusement. “I suspect those are wasted too. I know you well enough to know you have no particular delight in taking a seat in Council. But of course we are both too well trained in Comyn formalities to say so.” He bowed to Regis and went into the Crystal Chamber.

Perhaps these formalities were a good thing, Regis thought. How could Dyan and he ever exchange a civil word without them? He felt a great sadness, as if he had lost a friend without ever knowing him at all.

The honor guard, commanded today by Gabriel Lanart-Hastur, was directing the reseating of the Comyn; as the doors were closed, the Regent called them all to order.

“The next business of this assembly,” he said, “is to settle certain heirships within the Comyn. Lord Dyan Ardais, please come forward.”

Dyan, in his somber mourning, came and stood at the center of the rainbow lights.

“On the death of your father, Kyril-Valentine Ardais of Ardais, I call upon you, Dyan-Gabriel Ardais, to relinquish the state of Regent-heir to the Ardais Domain and assume that of Lord Ardais, with wardship and sovereignty over the Domain of Ardais and all those who owe them loyalty and allegiance. Are you prepared to assume wardship over your people?”

“I am prepared.”

“Do you solemnly declare that to your knowledge you are fit to assume this responsibility? Is there any man who will challenge your right to this solemn wardship of the people of your Domain, the people of all the Domains, the people of all Darkover?”

How many of them could truly declare themselves fit for that? Regis wondered. Dyan gave the proper answer.

“I will abide the challenge.”

Gabriel, as commander of the Honor Guard, strode to his side and drew Dyan’s sword. He called in a loud voice, “Is there any to challenge the worth and rightful wardship of Dyan-Gabriel, Lord of Ardais?”

There was a long silence. Hypocrisy, Regis thought. Meaningless formality. That challenge was not answered twice in a score of years, and even then it had nothing to do with fitness but with disputed inheritance! How long had it been since anyone seriously answered that challenge?

“I challenge the wardship of Ardais,” said a harsh and strident old voice from the ranks of the lesser peers. DomFelix Syrtis rose and slowly made his way toward the center of the room. He took the sword from Gabriel’s hand.

Dyan’s calm pallor did not alter, but Regis saw that his breathing had quickened. Gabriel said steadily, “Upon what grounds, DomFelix?”

Regis looked around quickly. As his sworn paxman and bodyguard, Danilo was seated just beside him. Danilo did not meet Regis’ eyes, but Regis could see that his fists were clenched. This was what Danilo had feared, if it came to his father’s knowledge.

“I challenge him as unfit,” DomFelix said, “on the grounds that he contrived unjustly the disgrace and dishonor of my son, while my son was a cadet in the Castle Guard. I declare blood-feud and call formal challenge upon him.”

Everyone sat silent and stunned. Regis picked up Gabriel Lanart-Hastur’s scornful thought, unguarded, that if Dyan had to fight a duel over every episode of that sort he’d be here fighting until the sun came up tomorrow, lucky for him he was the best swordsman in the Domains. But aloud Gabriel only said, “You have heard the challenge, Dyan Ardais, and you must accept it or refuse. Do you wish to consult with anyone before making your decision?”

“I refuse the challenge,” Dyan said steadily.

Unprecedented as the challenge itself had been, the refusal was even more unprecedented. Hastur leaned forward and said, “You must state your grounds for refusing a formal challenge, Lord Dyan.”

“I do so,” Dyan said, “on the grounds that the charge is justified.”

An audible gasp went around the room. A Comyn lord did not admit that sort of thing! Everyone in that room, Regis believed, must know the charge was justified. But everyone also knew that Dyan’s next act was to accept the challenge, quickly kill the old man and go on from there.

Dyan had paused only briefly. “The charge is just,” he repeated, “and there is no honor to be gained from the legal murder of an old man. And murder it would be. Whether his cause is just or unjust, a man of DomFelix’ years would have no equitable chance to prove it against my swordsmanship. And finally I state that it is not for him to challenge me. The son on whose behalf he makes this challenge is a man, not a minor child, and it is he, not his father, who should rightly challenge me in this cause. Does he stand ready to do it?” And he swung around to face Danilo where he sat beside Regis.

Regis heard himself gasp aloud.

Gabriel, too, looked shaken. But, as protocol demanded, he had to ask:

“ DomDanilo Syrtis. Do you stand ready to challenge Lord Dyan Ardais in this cause?”

DomFelix said harshly, “He does or I will disown him!”

Gabriel rebuked gently, “Your son is a man, DomFelix, not a child in your keeping. He must answer for himself.”

Danilo stepped into the center of the room. He said, “I am sworn paxman to Lord Regis Hastur. My Lord, have I your leave to make the challenge?” He was as white as a sheet. Regis thought desperately that the damned fool was no match for Dyan. He couldn’t just sit there and watch Dyan murder him to settle this grudge once and for all.

All his love for Danilo rebelled against this, but before his friend’s leveled eyes he knew he had no choice. He could not protect Dani. He said, “You have my leave to do whatever honor demands of you, kinsman. But there is no compulsion to do so. You are sworn to my service and by law that service takes precedence, so you have also my leave to refuse the challenge with no stain upon your honor.”

Regis was giving Dani an honorable escape if he wanted it. He could not, by Comyn immunity, fight Dyan in his place. But he could do this much.

Danilo made Regis a formal bow. He avoided his eyes. He went directly to Dyan, faced him and said, “I call challenge upon you, Lord Dyan.”

Dyan drew a deep breath. He was as pale as Danilo himself. He said, “I accept the challenge. But by law, a challenge of this nature may be resolved, at the option of the one challenged, by the offer of honorable amends. Is that not so, my lord Hastur?”

Regis could feel his grandfather’s confusion like his own, as the old Regent said slowly, “The law does indeed give you this option, Lord Dyan.”

Regis, watching him closely, could see the almost-involuntary motion of Dyan’s hand toward the hilt of his sword. This was the way Dyan had always settled all challenges before. But he steadied his hands, clasping them quietly before him. Regis could feel, like a bitter pain, Dyan’s grief and humiliation, but the older man said, in a harsh, steady voice, “Then, Danilo-Felix Syrtis, I offer you here before my peers and my kinsmen a public apology for the wrong done you, in that I did unjustly and wrongfully contrive your disgrace, by provoking you willfully into a breach of cadet rules and by a misuse of laran; and I offer you any honorable amends in my power. Will this settle the challenge and the blood-feud, sir?”

Danilo stood as if turned to stone. His face looked completely stunned.

Why did Dyan do it? Regis wondered. Dyan could have killed him now with impunity, legally, and the matter could never be raised against him again!

And suddenly, whether or not he received the answer directly from Dyan, or his own intuition, he knew: they had all had a lesson in what could happen when Comyn misused their powers. There was disaffection among the subjects and even among themselves, in their own ranks, their own sons turned against them. It was not only to their subjects that they must restore public trust in the integrity of the Comyn. If their own kinsmen lost faith in them they had lost all. And then, as for an instant Dyan looked directly at him, Regis knew the rest, right from Dyan’s mind:

I have no son. I thought it did not matter, then, whether I passed on an unsullied name. My father did not care what his son thought of him and I had no son to care.

Danilo was still standing motionless and Regis could feel his thoughts, too, troubled, uncertain: I have wanted for so long to kill him. It would be worth dying. But I am sworn to Regis Hastur, and sworn through him to the good of the Comyn. Dani drew a long breath and wet his lips before he could speak. Then he said, “I accept your honorable amends, Lord Dyan. And for myself and my house, I declare no feud remains and the challenge withdrawn—” Quickly he corrected himself: “The challenge settled.”

Dyan’s pallor was gradually replaced by a deep, crimson flush. He spoke almost breathlessly. “What amends will you ask, sir? Is it necessary to explain here, before all men, the nature of the injustice and the apology? It is your right … ”

Regis thought that Dani could make him crawl. He could have his revenge, after all.

Danilo said quietly, “It is not necessary, Lord Ardais. I have accepted your apology; I leave the amends to your honor.”

He turned quietly and returned to his place beside Regis. His hands were shaking. More advantages to the custom of formality, Regis thought wryly. Everyone knew, or guessed, and most of them probably guessed wrong. But now it need never be spoken.

Hastur spoke the formal words which confirmed Dyan’s legal status as Lord Ardais and warder of the Ardais Domain. He added: “It is required, Lord Ardais, that you designate an heir. Have you a son?”

Regis could feel, through the very air, his grandfather’s regret at the inflexibility of this ritual, which must only inflict more pain on Dyan. Dyan’s grief and pain, too, was a knife-edge to everyone there with laran. He said harshly, “The only son of my body, my legitimate heir, was killed four years ago in a rockslide at Nevarsin.”

“By the laws of the Comyn,” Hastur instructed him needlessly, “You must then name your choice of near kinsmen as heir-designate. If you later father a son, that choice may be amended,”