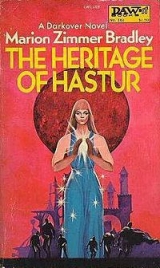

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

THE HERITAGE OF HASTUR

by Marion Zimmer Bradley

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Epilogue

next

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter ONE

As the riders came up over the pass which led down into Thendara, they could see beyond the old city to the Terran spaceport. Huge and sprawling, ugly and unfamiliar to their eyes, it spread like some strange growth below them. And all around it, ringing it like a scab, were the tightly clustered buildings of the Trade City which had grown between old Thendara and the spaceport.

Regis Hastur, riding slowly between his escorts, thought that it was not as ugly as they had told him in Nevarsin. It had its own beauty, an austere beauty of steel towers and stark white buildings, each for some alien and unknown purpose. It was not a cancer on the face of Darkover, but a strange and not unbeautiful garment.

The central tower of the new headquarters building faced the Comyn Castle, which stood across the valley, with an unfortunate aspect. It appeared to Regis that the tall skyscraper and the old stone castle were squared off and facing one another like two giants armed for combat

But he knew that was ridiculous. There had been peace between the Terran Empire and the Domains all of his lifetime. The Hasturs made sure of it

But the thought brought him no comfort. He was not much of a Hastur, he considered, but he was the last. They would make the best of him even though he was a damned poor substitute for his father, and everyone knew it. They’d never let him forget it for a minute.

His father had died fifteen years ago, just a month before Regis had been born. Rafael Hastur had at thirty-five already shown signs of being a strong statesman and leader, deeply loved by his people, respected even by the Terrans. And he had been blown to bits in the Kilghard Hills, killed by contraband weapons smuggled from the Terran Empire. Cut off in the full strength of his youth and promise, he had left only an eleven-year-old daughter and a fragile, pregnant wife. Alanna Elhalyn-Hastur had nearly died of the shock of his death. She had clung fitfully to life only because she knew she was carrying the last of the Hasturs, the longed-for son of Rafael. She had lived, racked with grief, just long enough for Regis to be born alive; then, almost with relief, she had laid her life down.

And after losing his father, after all his mother went through, Regis thought, all they got was him, not the son they would have chosen. He was strong enough physically, even good-looking, but curiously handicapped for a son of the telepathic caste of the Domains, the Comyn. A nontelepath. At fifteen, if he had inherited laranpower, he would have shown signs of it.

Behind him, he heard his bodyguards talking in low tones.

“I see they’ve finished their headquarters building. Hell of a place to put it, within a stone’s throw of Comyn Castle.”

“Well, they started to build it back in the Hellers, at Caer Donn. It was old Istvan Hastur, in my grandsire’s time, who made them move the spaceport to Thendara. He must have had his reasons.”

“Should have left it there, away from decent folk!”

“Oh, the Terrans aren’t all bad. My brother keeps a shop in the Trade City. Anyway, would you want the Terranan back in the hills, where those mountain bandits and the damned Aldarans could deal with them behind our backs?”

“Damned savages,” the second man said. “They don’t even observe the Compact back there. You see them in the Hellers, wearing their filthy cowards’ weapons.”

“What would you expect of the Aldarans?” They lowered their voices, and Regis sighed. He was used to it. He put constraint on everyone, just by being what he was: Comyn and Hastur. They probably thought he could read their minds. Most Comyn could.

“Lord Regis,” said one of his guards, “there’s a party of riders coming down the northward road carrying banners. They must be the party from Armida, with Lord Alton. Shall we wait for them and ride together?”

Regis had no particular desire to join another party of Comyn lords, but it would have been an unthinkable breach of manners to say so. At Council season all the Domains met together at Thendara; Regis was bound by the custom of generations to treat them all as kinsmen and brothers. And the Altons werehis kinsmen.

They slackened pace and waited for the other riders.

They were still high on the slopes, and he could see past Thendara to the spread-out spaceport itself. A great distant sound, like a faraway waterfall, made the ground vibrate like thunder, even where he stood. A tiny toylike form began to rise far out on the spaceport, slowly at first, then faster and faster. The sound peaked to a faint scream; the shape was a faraway streak, a dot, was gone.

Regis let his breath go. A starship of the Empire, outward bound for distant worlds, distant suns … Regis realized his fists had clenched so tightly on the reins that his horse tossed its head, protesting. He slackened them and gave the horse an absentminded, apologetic pat on the neck. His eyes were still riveted on the spot in the sky where the starship had vanished.

Outward bound, free for the immeasurable immensities of space, the ship was headed to worlds whose wonders he, chained down here, could never guess. His throat felt tight. He wished he were not too old to cry, but the heir to Hastur could not make any display of unmanly emotion in public. He wondered why he was getting so worked up about this, but he knew the answer: that ship was going where he could never go.

The riders from the pass were nearer now; Regis could identify some of them. Next to his bannerman rode Kennard, Lord Alton, a stooped, heavy-set man with red hair going gray. Except for Danvan Hastur, Regent of the Comyn, Kennard was probably the most powerful man in the Seven Domains. Regis had known Kennard all his life; as a child, he had called him uncle. Behind him, among a whole assembly of kinsmen, servants, bodyguards and poor relations, he saw the banner of the Ardais Domain, so Lord Dyan must be with them.

One of Regis’ guards said in an undertone, “I see the old buzzard has both his bastards with him. Wonder how he has the face?”

“Old Kennard can face anything, and make Hastur like it,” returned the other man in a prison-yard mutter. “Anyway, young Lew’s not a bastard; Kennard got him legitimated so he could work in the Arilinn Tower. The younger one—” The guard saw Regis glance his way and he stiffened; the expression slid off his face as if a sponge had wiped it blank.

Damn it, Regis thought irritably, I can’t read your mind, man, I’ve just got good, normal ears. But in any case, he realized, he had overheard an insolent remark about a Comyn lord, and the guard would have been embarrassed about that. There was an old proverb: The mouse in the walls may look at a cat, but he is wise not to squeak about it.

Regis, of course, knew the old story, Kennard had done a shocking, even a shameful thing: he had taken, in honorable marriage, a half-Terran woman, kin to the renegade Domain of Aldaran. Comyn Council had never accepted the marriage or the sons. Not even for Kennard’s sake.

Kennard rode toward Regis. “Greetings, Lord Regis. Are you riding to Council?”

Regis felt exasperated at the obviousness of the question—where else would he be going, on this road, at this season?—until he realized that the formal words implied recognition as an adult. He replied, with equally formal courtesy, “Yes, kinsman, my grandsire has requested that I attend Council this year.”

“Have you been all these years in the monastery at Nevarsin, kinsman?”

Kennard knew perfectly well where he had been, Regis reflected; when his grandfather couldn’t think of any other way to get Regis off his hands, he packed him away to Saint-Valentine-of-the-Snows. But it would have been a fearful breach of manners to mention this before the assembly so he merely said, “Yes, he entrusted my education to the cristoforos; I have been there three years.”

“Well, that was a hell of a way to treat the heir to Hastur,” said a harsh, musical voice. Regis looked up and recognized Lord Dyan Ardais, a pale, tall, hawk-faced man he had seen making brief visits to the monastery. Regis bowed and greeted him. “Lord Dyan.”

Dyan’s eyes, keen and almost colorless—there was said to be chieriblood in the Ardais—rested on Regis. “I told Hastur that only a fool would send a boy to be brought up in that place. But I gathered that he was much occupied with affairs of state, such as settling all the troubles the Terranan have brought to our world. I offered to have you fostered at Ardais; my sister Elorie bore no living child and would have welcomed a kinsman to rear. But your grandsire, I gather, thought me no fit guardian for a boy your age.” He gave a faint, sarcastic smile. “Well, you seem to have survived three years at the hands of the cristoforos. How was it in Nevarsin, Regis?”

“Cold.” Regis hoped that settled that.

“How well I remember,” Dyan said, laughing. “I was brought up by the brothers, too, you know. My father still had his wits then—or enough of them to keep me well out of sight of his various excesses. I spent the whole five years shivering.”

Kennard lifted a gray eyebrow. “I don’t remember that it was so cold.”

“But you were warm in the guesthouse,” Dyan said with a smile. “They keep fires there all year, and you could have had someone to warm your bed if you chose. The students’ dormitory at Nevarsin—I give you my solemn word—is the coldest place on Darkover. Haven’t you watched those poor brats shivering their way through the offices? Have they made a cristoforoof you, Regis?”

Regis said briefly, “No, I serve the Lord of Light, as is proper for a son of Hastur.”

Kennard gestured to two lads in the Alton colors, and they rode forward a little way. “Lord Regis,” he said formally, “I ask leave to present my sons: Lewis-Kennard Montray-Alton; Marius Montray-Lanart.”

Regis felt briefly at a loss. Kennard’s sons were not accepted by Council, but if Regis greeted them as kinsman and equals, he would give them Hastur recognition. If not, he would affront his kinsman. He was angry at Kennard for making this choice necessary, especially when there was nothing about Comyn etiquette or diplomacy that Kennard did not know.

Lew Alton was a tall, sturdy young man, five or six years older than Regis. He said with a wry smile, “It’s all right, Lord Regis, I was legitimated and formally designated heir a couple of years ago. It’s quite permissible for you to be polite to me.”

Regis felt his face flaming with embarrassment. He said, “Grandfather wrote me the news; I had forgotten. Greetings, cousin, have you been long on the road?”

“A few days,” Lew said. “The road is peaceful, although my brother, I think, found it a long ride. He’s very young for such a journey. You remember Marius, don’t you?”

Regis realized with relief that Marius, called Montray-Lanart instead of Alton because he had not yet been accepted as a legitimate son, was only twelve years old—too young in any case for a formal greeting. The question could be sidestepped by treating him as a child. He said, “You’ve grown since I last saw you, Marius. I don’t suppose you remember me at all. You’re old enough now to ride a horse, at least. Do you still have the little gray pony you used to ride at Armida?”

Marius answered politely, “Yes, but he’s out at pasture; he’s old and lame, too old for such a trip.”

Kennard looked annoyed. Diplomacy indeed! His grandfather would be proud of him, Regis considered, even if he was not proud of himself for the art of double tongues. Fortunately, Marius was not old enough to know he’d been snubbed. It occurred to Regis how ridiculous it was for boys their own age to address one another so formally anyway. Lew and he used to be close friends. The years at Armida, before Regis went to the monastery, they were as close as brothers. And now Lew was calling him Lord Regis! It was stupid!

Kennard looked at the sky. “Shall we ride on? It’s near sunset and sure to rain. It would be a nuisance to have to stop and pack away the banners. And your grandfather will be eager to see you, Regis.”

“My grandfather has been spared my presence for three years,” Regis said dryly. “I am sure he can endure another hour or so. But it would be better not to ride in the dark.”

Protocol said that Regis should ride beside Kennard and Lord Dyan, but instead he dropped back to ride beside Lew Alton. Marius was riding with a boy about Regis’ own age, who looked so familiar that Regis frowned, trying to recall where they’d met.

While the entourage was getting into line, Regis sent his banner-bearer to ride at the head of the column with those of Ardais and Alton. He watched the man ride ahead with the silver-and-blue fir-tree emblem of Hastur and the castaslogan, Permanedál. I shall remain, he translated wearily, yes, I shall stay here and be a Hastur whether I like it or not.

Then rebellion gripped him again. Kennard hadn’t stayed. He was educated on Terra itself, and by the will of the Council. Maybe there was hope for Regis too, Hastur or no.

He felt queerly lonely. Kennard’s maneuvering for proper respect for his sons had irritated him, but it had touched him too. If his own father had lived, he wondered, would he have been so solicitous? Would he have schemed and intrigued to keep his son from feeling inferior?

Lew’s face was grim, lonely and sullen. Regis couldn’t tell if he felt slighted, ill-treated or just lonely, knowing himself different

Lew said, “Are you coming to take a seat in Council, Lord Regis?”

The formality irritated Regis again. Was it a snub in return for the one he had given Marius? Suddenly he was tired of this. “You used to call me cousin, Lew. Are we too old to be friends?”

A quick smile lighted Lew’s face. He was handsome without the sullen, withdrawn look. “Of course not, cousin. But I’ve had it rubbed into me, in the cadets and elsewhere, that you are Regis-Rafael, Lord Hastur, and I’m … well, I’m nedestroheir to Alton. They only accepted me because my father has no proper Darkovan sons. I decided that it was up to you whether or not you cared to claim kin.”

Regis’ mouth stretched in a grimace. He shrugged. “Well, they may have to accept me, but I might as well be a bastard. I haven’t inherited laran.”

Lew looked shocked. “But certainly, you—I was sure—” He broke off. “Just the same, you’ll have a seat in Council, cousin. There isno other Hastur heir.”

“I’m all too well aware of that. I’ve heard nothing else since the day I was born,” Regis said. “Although, since Javanne married Gabriel Lanart, she’s having sons like kittens. One of them may very well displace me some day.”

“Still, you are in the direct line of male descent. A larangift does skip a generation now and then. All your sons could inherit it.”

Regis said with impulsive bitterness, “Do you think that helps—to know that I’m of no value for myself, but only for the sons I may have?”

A thin, fine drizzle of rain was beginning to fall. Lew drew his hood up over his shoulders and the insignia of the City Guard showed on his cloak. So he’s taking the regular duties of a Comyn heir, Regis thought. He may be a bastard, but he’s more useful than I am.

Lew said aloud, as if picking up his thoughts, “I expect you’ll be going into the cadet corps of the Guard this season, won’t you? Or are the Hasturs exempt?”

“It’s all planned out for us, isn’t it, Lew? Ten years old, fire-watch duty. Thirteen or fourteen, the cadet corps. Take my turn as an officer. Take a seat in Council at the proper time. Marry the right woman, if they can find one from a family that’s old enough and important enough and, above all, with laran. Father a lot of sons, and a lot of daughters to marry other Comyn sons. They’ve got our lives all planned, and all we have to do is go through the motions, ride their road whether we want to or not.”

Lew looked uneasy, but he didn’t answer. Obediently, like a proper prince, Regis drew a little ahead, to ride through the city gates in his proper place beside Kennard and Lord Dyan. His head was getting wet but, he thought sourly, it was his duty to be seen, to be put on display. A little thing like a soaking wasn’t supposed to bother a Hastur.

He forced himself to smile and wave graciously at the crowds lining the streets. But far away, through the very ground, he could hear again the dull vibration, like a waterfall. The starships were still there, he told himself, and the stars beyond them. No matter how deep they cut the track, I’ll find a way to break loose somehow. Someday.

previous | Table of Contents | next

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter TWO

(Lewis-Kennard Montray-Alton’s narrative)

I hadn’t wanted to attend Council this year. To be exact, I never wanted to attend Council at all. That’s putting it mildly. I’m not popular with my father’s equals in the Seven Domains.

At Armida, nothing bothers me. The house-folk know who I am and the horses don’t care. And at Arilinn nobody inquires about your family, your pedigree or your legitimacy. The only thing that matters in a Tower is your ability to manipulate a matrix and key into the energon rings and relay screens. If you’re competent, no one cares whether you were born between silk sheets in a great house or in a ditch beside the road; and if you’re not competent, you don’t come there at all.

You may ask why, if I was good at managing the estate at Armida, and more than adequate in the matrix relays at Arilinn, Father had this flea in his brain about forcing me on the Council. You may ask, but you’ll have to ask someone else. I have no idea.

Whatever his reasons, he had managed to force me on the Council as his heir. They hadn’t liked it, but they’d had to allow me the legitimate privileges of a Comyn heir and the duties that went with them. Which meant that at fourteen I had gone into the cadets and, after serving as a junior officer, was now a captain in the City Guard. It was a privilege I could have done without. The Council lords might be forced to accept me. But making the younger sons, lesser nobles and so forth who served in the cadets accept me—that was another song!

Bastardy, of course, is no special disgrace. Plenty of Comyn lords have half a dozen. If one of them turns out to have laran—which is what every woman who bears a child to a Comyn lord hopes for—nothing is easier than having the child acknowledged and given privileges and duties somewhere in the Domains. But to make one of them the heir-designate to the Domain, thatwas unprecedented, and every unacknowledged son of a minor line made me feel how little I merited this special treatment.

I couldn’t help knowing why they felt that way—I had what every one of them wanted, felt he merited as much as I did. But understanding only made things worse. It must be comfortable never to know whyyou’re disliked. Maybe then you can believe you don’t deserve it.

Just the same, I’ve made sure none of them could complain about me. I’ve done a little of everything, as Comyn heirs in the cadets are supposed to: I’ve supervised street patrols, organizing everything from grain supplies for the pack animals to escorts for Comyn ladies; I’ve assisted the arms-master at his job, and made sure that the man who cleaned the barracks knew hisjob. I disliked serving in the cadets and didn’t enjoy command duty in the Guard. But what could I do? It was a mountain I could neither cross nor go around. Father needed me and wanted me, and I could not let him stand alone.

As I rode at Regis Hastur’s side, I wondered if his choosing to ride beside me had been a mark of friendship or a shrewd attempt to get on the good side of my father. Three years ago I’d have said friendship, certainly. But boys change in three years, and Regis had changed more than most

He’d spent a few winters at Armida before he went to the monastery, before I went to Arilinn. I’d never thought about him being heir to Hastur. They said his health was frail; old Hastur thought that country living and company would do him good. He’d mostly been left to me to look after. I’d taken him riding and hawking, and he’d gone with me up into the plateaus when the great herds of wild horses were caught and brought down to be broken. I remembered him best as an undersized youngster, following me around, wearing my outgrown breeches and shirts because he kept growing out of his own; playing with the puppies and newborn foals, bending solemnly over the clumsy stitches he was learning to set in hawking-hoods, learning swordplay from Father and practicing with me. During the terrible spring of his twelfth year, when the Kilghard Hills had gone up in forest fires and every able-bodied man between ten and eighty was commandeered into the fire-lines, we’d gone together, working side by side by day, eating from one bowl and sharing blankets at night. We’d been afraid Armida itself would go up in the holocaust; some of the outbuildings were lost in the backfire. We’d been closer than brothers. When he went to Nevarsin, I’d missed him terribly. It was difficult to reconcile my memories of that almost-brother with this self-possessed, solemn young prince. Maybe he’d learned, in the interval, that friendship with Kennard’s nedestroheir was not quite the thing for a Hastur.

I could have found out, of course, and he’d never have known. But that’s not even a temptation for a telepath, after the first few months. You learn not to pry.

But he didn’t feelunfriendly, and presently asked me outright why I hadn’t called him by name; caught off guard by the blunt question, I gave him a straight answer instead of a diplomatic one and then, of course, we were all right again.

Once we were inside the gates, the ride to the castle was not long, just long enough to get thoroughly drenched. I could tell that Father was aching with the damp and cold—he’s been lame ever since I could remember, but the last few winters have been worse—and that Marius was wet and wretched. When we came into the lee of the castle it was already dark, and though the nightly rain rarely turns to snow at this season, there were sharp slashes of sleet in it. I slid from my horse and went quickly to help Father dismount, but Lord Dyan had already helped him down and given him his arm.

I withdrew. From my first year in the cadets, I’d made it a habit not to get any closer to Lord Dyan than I could possibly help. Preferably well out of reach.

There’s a custom in the Guards for first-year cadets. We’re trained in unarmed combat and we’re supposed to cultivate a habit of being watchful at all times; so during our first season, in the guardroom and armory, anyone superior to us in the Guards is allowed to take us by surprise, if he can, and throw us. It’s good training. After a few weeks of being grabbed unexpectedly from behind and dumped hard on a stone floor, you develop something like eyes in the back of your head. Usually it’s fairly good-natured, and although it’s a rough game and you collect plenty of bruises, no one really minds.

Dyan, we all agreed, enjoyed it entirely too much. He was an expert wrestler and could have made his point without doing much harm, but he was unbelievably rough and never missed a chance to hurt somebody. Especially me. Once he somehow managed to dislocate my elbow, which I wore in a sling for the rest of that season. He said it was an accident, but I’m a telepath and he didn’t even bother to conceal how much he had enjoyed doing it. I wasn’t the only cadet who had that experience. During cadet training, there are times when you hate all your officers. But Dyan was the only one we really feared.

I left Father to him and went back to Regis. “Someone’s looking for you,” I told him, pointing out a man in Hastur livery, sheltering in a doorway and looking wet and miserable, as if he’d been out in the weather, waiting, for some time. Regis turned eagerly to hear the message.

“The Regent’s compliments, Lord Regis. He has been urgently called into the city. He asks you to make yourself comfortable and to see him in the morning.”

Regis made some formal answer and turned to me with a humorless smile. “So much for the eager welcome of my loving grandsire.”

One hell of a welcome, indeed, I thought. No one could expect the Regent of Comyn to stand out in the rain and wait, but he could have sent more than a servant’s message! I said quickly, “You’ll come to us, of course. Send a message with your grandfather’s man and come along for some dry clothing and some supper!”

Regis nodded without speaking. His lips were blue with cold, his hair lying soaked on his forehead. He gave appropriate orders, and I went back to my own task: making sure that all of Father’s entourage, servants, bodyguards, Guardsmen, banner-bearers and poor relations, found their way to their appointed places.

Things gradually got themselves sorted out. The Guardsmen went off to their own quarters. The servants mostly knew what to do. Someone had sent word ahead to have fires lighted and the rooms ready for occupancy. The rest of us found our way through the labyrinth of halls and corridors to the quarters reserved, for the last dozen generations, to the Alton lords. Before long no one was left in the main hall of our quarters except Father, Marius and myself, Regis, Lord Dyan, our personal servants and half a dozen others. Regis was standing before the fire warming his hands. I remembered the night when Father had broken the news that he was to leave us and spend the next three years at Nevarsin. He and I had been sitting before the fire in the great hall at Armida, cracking nuts and throwing the shells into the fire; after Father finished speaking he had gone to the fire and stood there just like that, quenched and shivering, his face turned away from us all.

Damn the old man! Was there no friend, no kinswoman, he could send to welcome Regis home?

Father came to the fire. He was limping badly. He looked at Marius’ riding companion and said, “Danilo, I had your things sent directly to the cadet barracks. Shall I send a man to show you the way, or do you think you can find it?”

“There’s no need to send anyone, Lord Alton.” Danilo Syrtis came away from the fire and bowed courteously. He was a slender, bright-eyed boy of fourteen or so, wearing shabby garments which I vaguely recognized as once having been my brother’s or mine, long outgrown. That was like Father; he’d make sure that any protégé of his started with the proper outfit for a cadet. Father laid a hand on his shoulder. “You’re sure? Well, then, run along, my lad, and good luck go with you.”

Danilo, with a polite formula murmured vaguely at all of us, withdrew. Dyan Ardais, warming his hands at the fire, looked after him, eyebrows lifted. “Nice looking youngster. Another of your nedestrosons, Kennard?”

“Dani? Zandru’s hells, no! I’d be proud enough to claim him, but truly he’s none of mine. The family has Comyn blood, a few generations back, but they’re poor as miser’s mice; old DomFelix couldn’t give him a good start in life, so I got him a cadet commission.”

Regis turned away from the fire and said, “Danilo! I knew I should have recognized him; he was at the monastery one year. I truly couldn’t remember his name, Uncle. I should have greeted him!”

The word he used for uncle was the castaterm slightly more intimate than kinsman. I knew he had been speaking to my father, but Dyan chose to take it as addressed to himself. “You’ll see him in the cadets, surely. And I haven’t greeted you properly, either.” He came and took Regis in a kinsman’s embrace, pressing his cheek, to which Regis submitted, a little flustered; then, holding him at arm’s length, Dyan looked closely at him. “Does your sister hate you for being the beauty of the family, Regis?”

Regis looked startled and a little embarrassed. He said, laughing nervously, “Not that she ever told me. I suspect Javanne thinks I should be running around in a pinafore.”

“Which proves what I have always said, that women are no judge of beauty.” My father gave him a black scowl and said, “Damn it, Dyan, don’t tease him.”

Dyan would have said more—damn the man, was he starting that again, after all the trouble last year—but a servant in Hastur livery came in quickly and said, “Lord Alton, a message from the Regent.”

Father tore the letter open, began to swear volubly in three languages. He told the messenger to wait while he got into some dry clothes, disappeared into his room, and then I heard him shouting to Andres. Soon he came out, tucking a dry shirt into dry breeches, and scowling angrily.

“Father, what is it?

“The usual,” he said grimly, “trouble in the city. Hastur’s summoned every available Council elder and sending two extra patrols. Evidently a crisis of some sort.”

Damn, I thought. After the long ride from Armida and a soaking, to call him out at night … “Will you need me, Father?”

He shook his head. “No. Not necessary, son. Don’t wait up, I’ll probably be out all night.” As he went out, Dyan said, “I expect a similar summons awaits me in my own rooms; I had better go and find out. Good night, lads. I envy you your good night’s sleep.” He added, with a nod to Regis, “These others will never appreciate a proper bed. Only we who have slept on stone know how to do that.” He managed to make a deep formal bow to Regis and simultaneously ignore me completely—it wasn’t easy when we were standing side by side—and went away.

I looked around to see what remained to be settled. I sent Marius to change out of his drenched clothes—too old for a nanny and too young for an aide-de-camp, he’s left to me much of the time. Then I arranged to have a room made ready for Regis. “Have you a man to dress you, Regis? Or shall I have father’s body-servant wait on you tonight?”