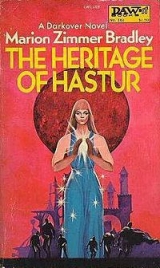

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

“After a fashion,” I said slowly. “I am his heir.” I did not want to discuss the costs of that with him. Not yet.

The steward had been trying to attract Lord Kermiac’s attention; he saw it and gave a signal for the tables to be cleared. As the great crowd who dined at his table began to disperse, he led me into a small sitting room, dimly lighted, a pleasant room with an open fireplace. He said, “I am old, and old men tire quickly, nephew. But before I go to rest, I want you to know your kinsmen. Nephew, your cousin, my son Beltran.”

To this day, even after all that came later, I still remember how I felt when I first looked on my cousin. I knew at last what blood had shaped me such a changeling among the Comyn. In face and feature we might have been brothers; I have known twins who were less like. Beltran held out his hand, drew it back and said, “Sorry, I have heard that telepaths don’t like touching strangers.”

“I won’t refuse a kinsman my hand,” I said, and returned the clasp lightly. In the strange mood I was in the touch gave me a swift pattern of impressions: curiosity, enthusiasm, a disarming friendliness. Kermiac smiled at us as we stood close together and said, “I leave your cousin to you, Beltran. Lew, believe me, you are at home.” He said good night and left us, and Beltran drew me toward the others. He said, “My father’s foster-children and wards, cousin, and my friends. Come and meet them. So you’re tower-trained? Are you a natural telepath as well?”

I nodded and he said, “Marjorie is our telepath.” He drew forward the pretty, red-haired girl in blue whom I had noticed at the table. She smiled, looking directly into my eyes in the way mountain girls have. She said, “I am a telepath, yes, but untrained; so many of the old things have been forgotten here in the mountains. Perhaps you can tell us what you were taught at Arilinn, kinsman.”

Her eyes were a strange color, a tint I had never seen before: gold-flecked amber, like some unknown animal. Her hair was almost red enough for the valley Comyn. I gave her my hand, as I had done with Beltran. It reminded me a little of the way the women at Arilinn had accepted me, simply as a human being, without fuss or flirtatiousness. I felt strangely reluctant to let her fingers go. I asked, “Are you a kinswoman?”

Beltran said, “Marjorie Scott, and her sister and brother, too, are my father’s wards. It’s a long story, he may tell you some day if he will. Their mother was my own mother’s foster-sister, so I call them, all three, sister and brother.” He drew the others forward and presented them. Rafe Scott was a boy of eleven or twelve, not unlike my own brother Marius, with the same gold-flecked eyes. He looked at me shyly and did not speak. Thyra was a few years older than Marjorie, a slight, restless, sharp-featured woman, with the family eyes but a look of old Kermiac, too. She met my eyes but did not offer her hand. ‘This is a long and weary journey for a lowlander, kinsman.”

“I had good weather and skilled escort for the mountains,” I said, bowing to her as I would have done to a lady of the Domains. Her dark features looked amused, but she was friendly enough, and for a little we talked of weather and the mountain roads. After a time Beltran drew the conversation back.

“My father was greatly skilled in his youth and has taught all of us some of the skills of a matrix technician. Yet I am said to have but little natural talent for it. You have had the training, Lew, so tell me, which is the most important, talent or skill?

I told him what I had been told myself. “Talent and skill are the right hand and the left; it is the will that rules both, and the will must be disciplined. Without talent, little skill can be learned; but talent alone is worth little without training.”

“I am said to have the talent,” said the girl Marjorie. “Uncle told me so, yet I have no skill, for by the time I was old enough to learn, he was old past teaching. And I am half-Terran. Could a Terran learn those skills, do you think?”

I smiled and said, “I too am part-Terran, yet I served at Arilinn—Marjorie?” I tried to speak her Terran name and she smiled at my stumbling formation of the syllables.

“ Marguerida, if you like that better,” she said softly in cahuenga. I shook my head. “As you speak it, it is rare and strange … and precious,” I said, wanting to add, “like you,” Beltran curled his lip disdainfully and said, “So the Comyn actually let you, with your Terran blood, into their sacred towers? How very condescending of them! I’d have laughed in their faces and told them what they could do with their tower!”

“No, cousin, it wasn’t like that,” I said. “It was only in the towers that no one took thought of my Terran blood. Among the Comyn I was nedestro, bastard. In Arilinn, no one cared what I was, only what I could do.”

“You’re wasting your time, Beltran,” said a quiet voice from near the fire. “I am sure he knows no more of history than any of the Hali’imyn, and his Terran blood has done him little good.” I looked across to the bench at the other side of the fire and saw a tall thin man, silver-gilt hair standing awry all around his forehead. His face was shadowed, but it seemed to me for a moment that his eyes came glinting out of the darkness like a cat’s eyes by torchlight. “No doubt he believes, like most of the valley-bred, that the Comyn fell straight from the arms of the Lord of Light, and has come to believe all their pretty romances and fairy tales. Lew, shall I teach you your own history?”

“Bob,” said Marjorie, “no one questions your knowledge. But your manners are terrible!”

The man gave a short laugh. I could see his features now by firelight, narrow and hawklike, and as he gestured I could see that he had six fingers on either hand, like the Ardais and Aillard men. There was something terribly strange about his eyes, too. He unfolded his long legs, stood up and made me an ironic bow.

“Must I respect the chastity of your mind, vai dom, as you respect that of your deluded sorceresses? Or have I leave to ravish you with some truths, in hope that they may bring forth the fruits of wisdom?”

I scowled at the mockery. “Who in hell are you?”

“In hell, I am no one at all,” he said lightly. “On Darkover, I call myself Robert Raymon Kadarin, s’dei par servu.” On his lips the elegant castawords became a mockery. “I regret I cannot follow your custom and add a long string of names detailing my parentage for generations. I know no more of my parentage than you Comyn know of yours but, unlike you, I have not yet learned to make up the deficiency with a long string of make-believe gods and legendary figures!”

“Are you Terran?” I asked. His clothing looked it.

He shrugged. “I was never told. However, it’s a true saying: only a race-horse or a Comyn lord is judged by his pedigree. I spent ten years in Terran Empire intelligence, though they wouldn’t admit it now; they’ve put a price on my head because, like all governments who buy brains, they like to limit what the brains are used for. I found out, for instance,” he added deliberately, “just what kind of game the Empire’s been playing on Darkover and how the Comyn have been playing along with them. No, Beltran,” he said, swinging around to face my cousin, “I’m going to tell him. He’s the one we’ve been waiting for.”

The harsh, disconnected way he spoke made me wonder if he was raving or drunk. “Just what do you mean, a game the Terrans are playing, with the Comyn to help?”

I had come here to find out if Aldaran was dangerously allied with Terra, to the danger of Comyn. Now this man Kadarin accused the Comyn of playing Terra’s games. I said, “I don’t know what in the hell you’re talking about. It sounds like rubbish.”

“Well, start with this,” Kadarin said. “Do you know who the Darkovans are, where we came from? Did anyone ever tell you that we’re the first and oldest of the Terran colonies? No, I thought you didn’t know that. By rights we should be equal to any of the planetary governments that sit in the Empire Council, doing our part to make the laws of the Empire, as other colonies do. We should be part of the galactic civilization we live in. Instead, we’re treated like a backward, uncivilized world, poor relations to be content with what crumbs of knowledge they’re willing to dole out to us drop by drop, kept carefully apart from the mainstream of the Empire, allowed to go on living as barbarians!”

“Why? If this is true, why?”

“Because the Comyn want it that way,” Kadarin said. “It suits their purposes. Don’t you even knowDarkover is a Terran colony? You said they mocked your Terran blood. Damn them, what do they think theyare? Terrans, all of them.”

“You’re stark raving mad!”

“You’d like to think so. So would they. More flattering, isn’t it to think of your father’s precious caste as being descended from gods and divinely appointed to rule all Darkover. Too bad! They’re just Terrans, like all the rest of the Empire colonies!” He stopped pacing and stood, staring down at us from his great height, he was a full head taller than I am, and I am not small. “I tell you, I’ve seen the records on Terra, and in the Administrative Archives on the Coronis colony. The facts are buried there, or supposed to be buried, but anybody with a security clearance can get them quickly enough.”

I demanded, “Where did you get all this stuff?” I could have used a much ruder word; out of deference to the women I used one meaning, literally, stable-sweepings.

He said, “Remarkable fertile stuff, stable-sweepings. Grows good crops. The facts are there. I have a gift for languages, like all telepaths—oh, yes, I am one, DomLewis. By the way, do you know you have a Terran name?”

“Surely not,” I said. Lewis had been a given name among the Altons for centuries.

“I have stood on the island of Lewis on Terra itself,” said the man Kadarin.

“Coincidence,” I said. “Human tongues evolve the same syllables, having the same vocal mechanism.”

“Your ignorance, DomLewis, is appalling,” said Kadarin coldly. “Some day, if you want a lesson in linguistics, you should travel in the Empire and hear for yourself what strange syllables the human tongue evolves for itself when there is no common language transmitted in culture.” I felt a sudden twinge of dread, like a cold wind. He went on. “Meanwhile, don’t make ignorant statements which only show what an untraveled boy you are. Virtually every given name ever recorded on Darkover is a name known on Terra, and in a very small part of Terra at that. The drone-pipe, oldest of Darkovan instruments, was known once on Terra, but they survive only in museums, the art of playing them lost; musicians came here to relearn the art and found music that survived from a very small geographical area, the British or Brictish Islands. Linguists studying your language found traces of three Terran languages. Spanish in your casta; English and Gaelic in your cahuenga, and the Dry-Town languages. The language spoken in the Hellers is a form of pure Gaelic which is no longer spoken on Terra but survives in old manuscripts. Well, to make a long tale short, as the old wife said when she cropped her cow’s brush, they soon found the record of a single ship, sent out before the Terran colonies had bound themselves together into the Empire, which vanished without trace and was believed crashed or lost. And they found the crewlist of that ship.”

“I don’t believe a word of it.”

“Your belief wouldn’t make it true; your doubt won’t make it false,” Kadarin said. “The very name of this world, Darkover, is a Terran word meaning,” he considered a minute, translated, “ ‘color of night overhead.’ On that crewlist there were di Asturiens and MacArans and these are, you would say, good old Darkovan names. There was a ship’s officer named Camilla Del Rey. Camilla is a rare name among Terrans now, but it is the most common name for girl-children in the Kilghard Hills; you have even given it to one of your Comyn demi-goddesses. There was a priest of Saint Christopher of Centaurus, a Father Valentine Neville, and how many of the Comyn’s sons have been taught in the cristoforomonastery of Saint-Valentine-of-the-Snows? I brought Marjorie, who is a cristoforo, a little religious medal from Terra itself; its twin is enshrined in Nevarsin. Must I go on with such examples, which I assure you I could quote all night without tiring? Have your Comyn forefathers ever told you so much?’

My head was reeling. It sounded infernally convincing.

“The Comyn cannot know this. If the knowledge was lost—”

“They know, all right,” Beltran said with contempt. “Kennard knows certainly. He has lived on Terra.”

My father knew this and had never told me?

Kadarin and Beltran were still telling me their tale of a “lost ship” but I had ceased to listen. I could sense Marjorie’s soft eyes on me in the dying firelight, though I could no longer see them. I felt that she was following my thoughts, not intruding on them but rather responding to me so completely that there were no longer any barriers between us. This had never happened before. Even at Arilinn, I had never felt so wholly attuned to any human being. I felt she knew how distressed and weary all this had made me.

On the cushioned bench she stretched out her hand to me and I could feel her indignation running up from her small fingers into my hand and arm and all along my body. She said, “Bob, what are you trying to doto him? He comes here weary from long travel, a kinsman and a guest; is this our mountain hospitality?”

Kadarin laughed. “Set a mouse to guard a lion!” he said. I felt those unfathomably strange eyes piercing the darkness to see our hands clasped. “I have my reasons, child. I don’t know what fate sent him here, but when I see a man who has lived by a lie, I try to tell him the truth if I feel he’s worth hearing it. A man who must make a choice must make it on facts, not fuzzy loyalties and half-truths and old lies. The tides of fate are moving—”

I said rudely, “Is fate one of your facts? You called mesuperstitious.”

He nodded. He looked very serious. “You’re a telepath, an Alton; you know what precognition is.”

Beltran said, “You’re going too fast. We don’t even know why he’s come here, and he isheir to a Domain. He may even have been sent to carry tales back to the old graybeard in Thendara and all his deluded yes-men.”

Beltran swung around to face me. “Why didyou come here?” he demanded. “After all these years, Kennard cannot be all that eager for you to know your mother’s kin, otherwise you would have been my foster-brother, as Father wished.”

I thought of that with a certain regret. I would willingly have had this kinsman for foster-brother. Instead I had never known of his existence till now, and it had been our mutual loss. He demanded again, “Why have you come, cousin, after so long?”

“It’s true I came at my father’s will,” I said at last, slowly. “Hastur heard reports that the Compact was being violated in Caer Donn: my father was too ill to travel and sent me in his place.” I felt strangely pulled this way and that. Had Father sent me to spy on kinsfolk? The idea filled me with revulsion. Or had he, in truth, wished me to know my mother’s kin? I did not know, and not knowing made me uncertain, wretched.

“You see,” said the woman Thyra, from her place in Kadarin’s shadow, “it’s useless to talk to him. He’s one of the Comyn puppets.”

Anger flared through me. ‘I am no man’s puppet. Not Hastur’s. Not my father’s. Nor will I be yours, cousin or no. I came at my free will, because if Compact is broken it touches all our lives. And more than that, whatever my father said, I wished to know for myself whether what they had told me of Aldaran and Terra was true.”

“Spoken honestly,” Beltran said. “But let me ask you this, cousin. Is your loyalty to Comyn … or to Darkover?”

Asked that question at almost any other time, I would have said, without hesitation, that to be loyal to Comyn was to be loyal to Darkover. Since leaving Thendara I was no longer so sure. Even those I wholly trusted, like Hastur, had no power, or perhaps no wish, to check the corruption of the others. I said, ‘To Darkover. No question, to Darkover.”

He said vehemently, “Then you should be one of us! You were sent to us at this moment, I think, because we needed you, because we couldn’t go on without someone like you!”

“To do what?” I wanted no part in any Aldaran plots.

“Only this, kinsman, to give Darkover her rightful place, as a world belonging to our own time, not a barbarian backwater! We deserve the place on the Empire Council which we should have had, centuries ago, if the Empire had been honest with us. And we are going to have it!”

“A noble dream,” I said, “if you can manage it. Just how are you going to bring this about?”

“It won’t be easy,” Beltran said. “It’s suited the Empire, and the Comyn, to perpetuate their idea of our world: backward, feudal, ignorant. And we have become many of these things.”

“Yet,” Thyra said from the shadows, “we have one thing which is wholly Darkovan and unique. Our psi powers.” She leaned forward to put a log on the fire and I saw her features briefly, lit by flame, dark, vital, glowing. I said, “If they are unique to Darkover, what of your theory that we are all Terrans?”

“Oh, yes,” she said, “these powers are all recorded and remembered on Terra. But Terra neglected the powers of the mind, concentrating on material things, metal and machinery and computers. So their psi powers were forgotten and bred out. Instead we developed them, deliberately bred for them—that much of the Comyn legend is true. And we had the matrix jewels which convert energy. Isolation, genetic drift and selective breeding did the rest. Darkover is a reservoir of psi power and, as far as I know, is the only planet in the galaxy which turned to psi instead of technology.”

“Even with matrix amplification, these powers are dangerous,” I said. “Darkovan technology has to be used with caution, and sparsely. The price, in human terms, is usually too high.”

The woman shrugged. “You cannot take hawks without climbing cliffs,” she said.

“Just what is it you intend to do?”

“Make the Terrans take us seriously!”

“You don’t mean war?” That sounded like suicidal nonsense and I said so. “Fight the Terrans, weapons against weapons?”

“No. Or only if they need to be shown that we are neither ignorant nor helpless,” Kadarin said. “A high-level matrix, I understand, is a weapon to make even the Terrans tremble. But I hope and trust it will never come to that. The Terran Empire prides itself on the fact that they don’t conquer, that planets askto be admitted to the Empire. Instead, the Comyn committed Darkover to withdrawal, barbarianism, a search for yesterday, not tomorrow. We have something to give the Empire in return for what they give us, our matrix technology. We can join as equals, not suppliants. I have heard that in the old days there were matrix-powered aircraft in Arilinn—”

“True,” I said, “as recently as in my father’s time.”

“And why not now?” He did not wait for me to answer. “Also, we could have a really effective communications technique—”

“We have that now.”

“But the towers work only under Comyn domination, not for the entire population of the world.”

“The risks—”

“Only the Comyn seem to know anything about those risks,” Beltran said. “I’m tired of letting the Comyn decide for everyone else what risks we may take. I want us to be accepted as equals by the Terrans. I want us to be part of Terran trade, not just the trickle which comes in and out by the spaceports under elaborate permits signed and countersigned by their alien culture specialists to make certain it won’t disturb our primitive culture! I want good roads and manufacturing and transportation and some control over the God-forgotten weather on this world! I want our students in the Empire universities, and theirs coming here! Other planets have these things! And above all I want star-travel. Not as a rich man’s toy, as with the Ridenow lads spending a season now and then on some faraway pleasure world and bringing back new toys and new debaucheries, but free trade, with Darkovan ships coming and going at our will, not the Empire’s!”

“Daydreams,” I said flatly. “There’s not enough metal on Darkover for a spaceship’s hulk, let alone fuel to power it!”

“We can trade for metal,” Beltran said. “Do you think matrices, manned by psi power, won’t power a spaceship? And wouldn’t that make most of the other power sources in the Galaxy obsolete overnight?”

I stood motionless for a moment, gripped by the force of his dream. Starships for Darkover … matrix-powered! By all the Gods, what a dream! And Darkovans comrades, competitors, not forgotten stepchildren of the Empire …

“It can’t be possible,” I said, “or the matrix circles would have done it in the old days.”

“It wasdone,” Kadarin said. “The Comyn stopped it. It would have diluted their power on this world. We turned our back on a Galactic civilization because that crew of old women in Thendara decided they liked our world the way it was, with the Comyn up there with the Gods and everyone else running around bowing and scraping to them! They even disarmed us all. Their precious Compact sounds very civilized, but what it’s done, in effect, is to make it impossible to organize any kind of armed rebellion that could endanger the Comyn’s power!”

This went along, all too uncomfortably, with some of my own thoughts. Even Hastur spoke noble words about the Comyn devoting themselves to the service of Darkover, but what it came to was that he knew what was best for Darkover, and wanted no independent ideas challenging his power to enforce that “best.”

“It’s a noble dream. I said that before. But what have I to do with it?”

It was Marjorie who answered, squeezing my hand eagerly. “Cousin, you’re tower-trained. You know the skills and techniques, and how they can be used even by latent telepaths. So much of the old knowledge has been lost, outside the towers. We can only experiment, work in the dark. We don’t have the skills, the disciplines with which we could experiment further. Those of us who are telepaths have no chance to develop our natural gifts; those who are not have no way to learn the mechanics of matrix work. We need someone—someone like you, cousin!”

“I don’t know … I have only worked within the towers. I have been taught it is not safe … ”

“Of course,” Kadarin said contemptuously. “Would they risk any trained man experimenting on his own and perhaps learning more than the little they allow? Kermiac was training matrix technicians here in the Hellers when you people in the Domains were still working in guarded circles, looked on as sorceresses and warlocks! But he is very old and he cannot guide us now.” He smiled, a brief, bleak smile. “We need someone who is young and skilled and above all fearless. I think you have the strength for it. Have you the will?”

I found myself recalling the fey sense of destiny which had gripped me as I rode here. Was this the destiny I had foreseen, to break the hold of a corrupt clan on Darkover, to overthrow their grip at our throats, set Darkover in its rightful place among the equals of the Empire?

It was almost too much to grasp. I was suddenly very tired. Marjorie, still stroking my hand gently in her small fingers, said without looking up, “Enough, Beltran, give him time. He’s weary from traveling and you’ve been jumping at him till he’s confused. If it’s right for him, he’ll decide.”

She was thinking of me. Everyone else was thinking of how well I could fit into their plans.

Beltran said with a rueful, friendly smile, “Cousin, my apologies! Marjorie is right, enough for now! After that long journey, you’re more in need of a quiet drink and a soft bed than a lecture on Darkovan history and politics! Well, the drink for now and the bed soon, I promise!” He called for wine and a sweet fruit-flavored cordial not unlike the shallanwe drank in the valley. He raised his glass to me. “To our better acquaintance, cousin, and to a pleasant stay among us.”

I was glad to drink to that. Mariorie’s eyes met mine over the rim of her glass. I wanted to take her hand again. Why did she appeal to me so? She looked young and shy, with an endearing awkwardness, but in the classic sense, she was not beautiful. I saw Thyra sitting within the curve of Kadarin’s arm, drinking from his cup. Among valley folk that would have proclaimed them admitted lovers. I didn’t know what, if anything, it meant here. I wished I were free to hold Marjorie like that.

I turned my attention to what Beltran was saying, about Terran methods used in the rapid building of Caer Donn, of the way in which trained telepaths could be used for weather forecasting and control. “Every planet in the Empire would send people here to be trained by us, and pay well for the privilege.”

It was all true, but I was tired, and Beltran’s plans were so exciting I feared I would not sleep. Besides, my nerves were raw-edged with trying to keep my awareness of Marjorie under control. I felt I would rather be beaten into bleeding pulp than intrude, even marginally, on her sensitivities. But I kept wanting to reach out to her, test her awareness of me, see if she shared my feelings or if her kindness was the courtesy of a kinswoman to a wearied guest …

“Beltran,” I said at last, cutting off the flow of enthusiastic ideas, “there’s one serious flaw in your plans. There just aren’t enough telepaths. We haven’t enough trained men and women even to keep all nine of the towers operating. For such a galactic plan as you’re contemplating, we’d need dozens, hundreds.”

“But even a latent telepath can learn matrix mechanics,” he said. “And many who have inherited the gifts never develop them. I believed the tower-trained could awaken latent laran.”

I frowned. “The Alton gift is to force rapport. I learned to use it in the towers to awaken latents if they weren’t too barricaded. I can’t always do it. That demands a catalyst telepath. Which I’m not.”

Thyra said sharply, “I told you so, Bob. Thatgene’s extinct.”

Something in her tone made me want to contradict her. “No, Thyra,” I said, “I know of one. He’s only a boy, and untrained, but definitely a catalyst telepath. He awakened laranin a latent, even after I failed.”

“Much good that does us,” Beltran said in disgust. “Comyn Council has probably bound him so tight, with favors and patronage, that he’ll never see beyond their will! They usually do, with telepaths. I’m surprised they haven’t already bribed and bound you that way.”

I thought, but did not say, that they had tried.

“No,” I said, “they have not. Dani has no reason at all to love the Comyn … and reason enough to hate.”

I smiled at Marjorie and began to tell them about Danilo and the cadets.

previous | Table of Contents | next