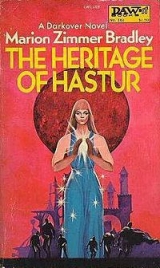

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter SIX

(Lew Alton’s narrative)

Father was bedridden during the first several days of Council season, and I was too busy and beset to have much time for the cadets. I had to attend Council meetings, which at this particular time were mostly concerned with some dreary business of trade agreements with the Dry Towns. One thing I did find time for was having that staircase fixed before someone else broke his leg, or his neck. This was troublesome too: I had to deal with architects and builders, we had stonemasons underfoot for days, the cadets coughed from morning to night with the choking dust and the veterans grumbled constantly about having to go the long way round and use the other stairs.

A long time before I thought he was well enough, Father insisted on returning to his Council seat, which I was glad to be out of. Far too soon after that, he returned to the Guards, his arm still in a sling, looking dreadfully pale and worn. I suspected he shared some of my uneasiness about how well the cadets would fare this season, but he said nothing about it to me. It nagged at me ceaselessly; I resented it as much for my father’s sake as my own. If my father had chosen to trust Dyan Ardais, I might not have been quite so disturbed. But I felt that he, too, had been compelled, and that Dyan had enjoyed having the power to do so.

A few days after that, Gabriel Lanart-Hastur returned from Edelweiss with news that Javanne had borne twin girls, whom she named Ariel and Liriel. With Gabriel at hand, my father sent me back into the hills on a mission to set up a new system of fire-watch beacons, to inspect the fire-watch stations which had been established in my grandfather’s day and to instruct the Rangers in new fire-fighting techniques. This kind of mission demands tact and some Comyn authorty, to persuade men separated by family feuds and rivalries, sometimes for generations, to work together peacefully. Fire-truce is the oldest tradition on Darkover but, in districts which have been lucky enough to escape forest fires for centuries, it’s hard to persuade anyone that the fire-truce should be extended to the upkeep of the stations and beacons.

I had my father’s full authority, though, and that helped. The law of the Comyn transcends, or is supposed to transcend, personal feuds and family rivalries. I had a dozen Guardsmen with me for the physical work, but I had to do the talking, the persuading and the temper-smoothing when old struggles flared out of control. It took a lot of tact and thought; it also demanded knowledge of the various families, their hereditary loyalties, intermarriages and interactions for the last seven or eight generations. It was high summer before I rode back to Thendara, but I felt I’d accomplished a great deal. Every step against the constant menace of forest fire on Darkover impresses me more than all the political accomplishments of the last hundred years. That’s something we’ve actually gained from the presence of the Terran Empire: a great increase in knowledge of fire-control and an exchange of information with other heavily wooded Empire planets about new methods of surveillance and protection.

And back in the hills the Comyn name meant something. Nearer to the Trade Cities, the influence of Terra has eroded the old habit of turning to the Comyn for leadership. But back there, the potency of the very name of Comyn was immense. The people neither knew nor cared that I was a half-Terran bastard. I was the son of Kennard Alton, and that was all that really mattered. For the first time I carried the full authority of a Comyn heir.

I even settled a blood-feud which had run three generations by suggesting that the eldest son of one house marry the only daughter of another and the disputed land be settled on their children. Only a Comyn lord could have suggested this without becoming himself entangled in the feud, but they accepted it. When I thought of the lives it would save, I was glad of the chance.

I rode into Thendara one morning in midsummer. I’ve heard offworlders say our planet has no summer, but there had been no snow for three days, even in the pre-dawn hours, and that was summer enough for me. The sun was dim and cloud-hidden, but as we rode down from the pass it broke through the layers of fog, throwing deep crimson lights on the city lying below us. Old people and children gathered inside the city gates to watch us, and I found I was grinning to myself. Part of it, of course, was the thought of being able to sleep for two nights in the same bed. But part of it was pure pleasure at knowing I’d done a good job. It seemed, for the first time in my life, that this was my city, that I was coming home. I had not chosen this duty—I had been born into it—but I no longer resented it so much.

Riding into the stable court of the Guards, I saw a brace of cadets on watch at the gates and more going out from the mess hall. They seemed a soldierly lot, not the straggle of awkward children they had been that first day. Dyan had done well enough, evidently. Well, it had never been his competence I questioned, but even so, I felt better. I turned my horse over to the grooms and went to make my report to my father.

He was out of bandages now, with his arm free of the sling, but he still looked pale, his lameness more pronounced than ever. He was in Council regalia, not uniform. He waved away my proffered report.

“No time for that now. And I’m sure you did as well as I could have done myself. But there’s trouble here. Are you very tired?”

“No, not really. What’s wrong, Father? More riots?”

“Not this time. A meeting of Council with the Terran Legate this morning. In the city, at Terran headquarters.”

“Why doesn’t he wait on you in the Council Chamber?” Comyn lords did not come and go at the bidding of the Terranan!

He caught the thought and shook his head. “It was Hastur himself who requested this meeting. It’s more important than you can possibly imagine. That’s why I want you to handle this for me. We need an honor guard, and I want you to choose the members very carefully. It would be disastrous if this became a subject of gossip in the Guards—or elsewhere.”

“Surely, Father, any Guardsman would be honor-bound—”

“In theory, yes,” he said dryly, “but in practice, some of them are more trustworthy than others. You know the younger men better than I do.” It was the first time he had ever admitted so much. He had missed me, needed me. I felt warmed and welcomed, even though all he said was, “Choose Guardsmen or cadets who are blood-kin to Comyn if you can, or the trustiest. You know best which of them have tongues that rattle at both ends.”

Gabriel Lanart, I thought, as I went down to the Guard hall, an Alton kinsman, married into the Hasturs. Lerrys Ridenow, the younger brother of the lord of his Domain. Old di Asturien, whose loyalty was as firm as the foundations of Comyn Castle itself. I left him to choose the veterans who would escort us through the streets—they would not go into the meeting rooms, so their choice was not so critical—and went off to cadet barracks.

It was the slack time between breakfast and morning drill. The first-year cadets were making their beds, two of them sweeping the floor and cleaning out the fireplaces. Regis was sitting on the corner cot, mending a broken bootlace. Was it meekness or good nature which had let them crowd him into the drafty spot under the window? He sprang up and came to attention as I stopped at the foot of his bed.

I motioned him to relax. “The Commander has sent me to choose an honor guard detail,” I said. “This is Comyn business; it goes without saying that no word of what you may hear is to go outside Council rooms. Do you understand me, Regis?”

“Yes, Captain.” He was formal, but I caught curiosity and excitement in his lifted face. He looked older, not quite so childish, not nearly so shy. Well, as I knew from my own first tormented cadet season, one of two things happened in the first few days. You grew up fast … or you crawled back home, beaten, to your family. I’ve often thought that was why cadets were required to serve a few terms in the Guard. No one could ever tell in advance which ones would survive.

I asked, “How are you getting along?”

He smiled, “Well enough.” He started to say something else, but at that moment Danilo Syrtis, covered in dust, crawled out from under his bed. “Got it!” he said. “It evidently slipped down this morning when I—” He saw me, broke off and came to attention.

“Captain.”

“Relax, cadet,” I said, “but you’d better get that dirt off your knees before you go out to inspection.” He was father’s protégé, and his family had been Hastur men for generations. “You join the honor guard too, cadet. Did you hear what I said to Regis, Dani?”

He nodded, coloring, and his eyes brightened. He said, with such formality that it sounded stiff, “I am deeply honored, Captain.” But through the formal words, I caught the touch of excitement, apprehension, curiosity, unmistakable pleasure at the honor.

Unmistakable. This was not the random sensing of emotions which I pick up in any group, but a definite touch.

Laran. The boy had laran, was certainly a telepath, probably had one of the other gifts. Well, it was not much of a surprise. Father had told me they had Comyn blood a few generations back. Regis was kneeling before his chest, searching for the leather tabard of his dress uniform. As Danilo was about to follow suit, I stepped to his side and said, “A word, kinsman. Not now—there is no urgency—but some time, when you are free of other duties, go to my father, or to Lord Dyan if you prefer, and ask to be tested by a leronis. They will know what you mean. Say that it was I who told you this.” I turned away. “Both of you join the detail at the gates as soon as you can.”

The Comyn lords were waiting in the court as the detail of Guards was forming. Lord Hastur, in sky-blue cloak with the silver fir tree badge. My father, giving low-voiced directions to old di Asturien. Prince Derik was not present. Hastur would have had to speak for him as Regent in any case, but Derik at sixteen should certainly have been old enough, and interested enough, to attend such an important meeting.

Edric Ridenow was there, the thickset, red-bearded lord of Serrais. There was also a woman, pale and slender, folded in a thin gray hooded cloak which shielded her from curious eyes. I did not recognize her, but she was evidently comynara; she must be an Aillard or an Elhalyn, since only those two Domains give independent Council right to their women. Dyan Ardais, in the crimson and gray of his Domain, strode to his place; he gave a brief glance to the honor guard, stopped briefly beside Danilo and spoke in a low voice. The boy blushed and looked straight ahead. I’d already noticed that he still colored like a child if you spoke to him. I wondered what small fault the cadet-master had found in his appearance and bearing. I had found none, but it’s a cadet-master’s business to take note of trivialities.

As we moved through the streets of Thendara, we drew surprised glances. Damn the Terrans anyway! It lessened Comyn dignity, that they beckoned and we came at a run!

The Regent seemed conscious of no loss of dignity. He moved between his escort with the energy of a man half his years, his face stern and composed. Just the same I was glad when we reached the spaceport gates. Leaving the escort outside, we were conducted, Comyn lords and honor guard, into the building to a large room on the first floor.

As custom decreed, I stepped inside first, drawn sword in hand. It was small for a council chamber, but contained a large, round table and many seats. A number of Terrans were seated on the far side of the table, mostly in some sort of uniform. Some of them wore a great number of medals, and I surmised they intended to do the Comyn honor.

Some of them showed considerable unease when I stepped inside with my drawn sword, but the gray-haired man at their center—the one with the most medals—said quickly, “It is customary, their honor guard. You come for the Regent of Comyn, officer?”

He had spoken cahuenga, the mountain dialect which has become a common tongue all over Darkover, from the Hellers to the Dry Towns. I brought my sword up to salute and replied, “Captain Montray-Alton, at your service, sir.” Since I saw no weapons visible anywhere in the room, I forebore any further search and sheathed the sword. I ushered in the rest of the honor guard, placing them around the room, motioning Regis to take a position directly behind the Regent, stationing Gabriel at the doorway, then ushering in the members of the Council and announcing their names one by one.

“Danvan-Valentine, Lord Hastur, Warden of Elhalyn, Regent of the Crown of the Seven Domains.”

The gray-haired man—I surmised that he was the Terran Legate—rose to his feet and bowed. Not deeply enough, but more than I’d expected of a Terran. “We are honored, Lord Regent,”

“Kennard-Gwynn Alton, Lord Alton, Commander of the City Guard.” He limped heavily to his place.

“Lord Dyan-Gabriel, Regent of Ardais.” Whatever my personal feelings about him, I had to admit he looked impressive. “Edric, Lord Serrais. And—” I hesitated a moment as the gray-cloaked woman entered, realized I did not know her name. She smiled almost imperceptibly and murmured under her breath, “For shame, kinsman! Don’t you recognize me? I am Callina Aillard.”

I felt like an utter fool. Of course I knew her.

“Callina, Lady Aillard—” I hesitated again momentarily; I could not remember in which of the towers she was serving as Keeper. Well, the Terrans would never know the difference. She supplied it telepathically, with an amused smile behind her hood, and I concluded, “ leronisof Neskaya.”

She walked with quiet composure to the remaining seat. She kept the hood of her cloak about her face, as was proper for an unwedded woman among strangers. I saw with some relief that the Legate, at least, had been informed of the polite custom among valley Darkovans and had briefed his men not to look directly at her. I too kept my eyes politely averted; she was my kinswoman, but we were among strangers. I had seen only that she was very slight, with pale solemn features.

When everyone was in his appointed place, I drew my sword again, saluted Hastur and then the Legate and took my place behind my father. One of the Terrans said, “Now that all that’s over, can we come to business?”

“Just a moment, Meredith,” the Legate said, checking his unseemly impatience. “Noble lords, my lady, you lend us grace. Allow me to present myself. My name is Donnell Ramsay; I am privileged to serve the Empire as Legate for Terra. It is my pleasure to welcome you. These”—he indicated the men beside him at the table—“are my personal assistants: Laurens Meredith, Reade Andrusson. If there are any among you, my lords, who do not speak cahuenga, our liaison man, Daniel Lawton, will be honored to translate for you into the casta. If we may serve you otherwise, you have only to speak of it. And if you wish, Lord Hastur,” he added, with a bow, “that this meeting should be conducted according to formal protocol in the castalanguage, we are ready to accede.”

I was glad to note that he knew the rudiments of courtesy. Hastur said, “By your leave, sir, we will dispense with the translator, unless some misunderstanding should arise which he can settle. He is, however, most welcome to remain.”

Young Lawton bowed. He had flaming red hair and a look of the Comyn about him. I remembered hearing that his mother had been a woman of the Ardais clan. I wondered if Dyan recognized his kinsman and what he thought about it.

It was strange to think that young Lawton might well have been standing here among the honor guard. My thoughts were wandering; I commanded them back as Hastur spoke.

“I have come to you, Legate, to draw your attention to a grave breach of the Compact on Darkover. It has been brought to my notice that, back in the mountains near Aldaran, a variety of contraband weapons is being openly bought and sold. Not only within the Trade City boundaries there, where your agreement with us allows your citizens to carry what weapons they will, but in the old city of Caer Donn, where Terrans walk the streets as they wish, carrying pistols and blasters and neural disrupters. I have also been told that it is possible to purchase these weapons in that city, and that they have been sold upon occasion to Darkovan citizens. My informant purchased one without difficulty. It should not be necessary to remind you that this is a very serious breach of Compact.”

It took all my self-control to keep the impassive face suitable for an honor guard, whose perfect model is a child’s carved toy soldier, neither hearing nor seeing. Would even the Terrans dare to breach the Compact?

I knew now why my father had wanted to be certain no hint of gossip got out. Since the Ages of Chaos, the Darkovan Compact has banned any weapon operating beyond the hand’s reach of the man wielding it. This was a fundamental law: the man who would kill must himself come within reach of death. News that the Compact was being violated would shake Darkover to the roots, create public disorder and distrust, damage the confidence of the people in their rulers.

The Legate’s face betrayed nothing, yet something, some infinitesimal tightening of his eyes and mouth, told me this was no news to him.

“It is not our business to enforce the Compact on Darkover, Lord Hastur. The policy of the Empire is to maintain a completely neutral posture in regard to local disputes. Our dealings in Caer Donn and the Trade City there are with Lord Kermiac of Aldaran. It was made very clear to us that the Comyn have no jurisdiction in the mountains near Aldaran. Have I been misinformed? Is the territory of Aldaran subject to the laws of Comyn, Lord Hastur?”

Hastur said with a snap of his jaw, “Aldaran has not been a Comyn Domain for many years, Mr. Ramsay. Nevertheless, the Compact can hardly be called a local decision. While Aldaran is not under our law—”

“So I myself believed, sir,” the Legate said, “and therefore—”

“Forgive me, Mr. Ramsay, I had not yet finished.” Hastur was angry. I tried to keep myself barriered, as any telepath would in a crowd this size, but I couldn’t shut out everything. Hastur’s calm, stern face did not alter a muscle, but his anger was like the distant glow of a forest fire against the horizon. Not yet a danger, but a faraway menace. He said, “Correct me if I am wrong, Mr. Ramsay, but is it not true that when the Empire negotiated to have Darkover given status as a Class D Closed World”—the technical language sounded strange on his tongue, and he seemed to speak it with distaste—“that one condition of the use and lease of the spaceport and the establishment of the cities of Port Chicago, Caer Donn and Thendara as Trade Cities, was complete enforcement of Compact outside the Trade Cities and control of contraband weapons? Mindful of that agreement, can you truthfully state that it is not your business to enforce the Compact on Darkover, sir?”

Ramsay said, “We did and we do enforce it in the Comyn Domains and under Comyn law, my lord, at considerable trouble and expense to ourselves. Need I remind you that one of our men was threatened with murder, not long ago, because he was unweaponed and defenseless in a society which expects every man to fight and protect himself?”

Dyan Ardais said harshly, “The episode you mention was unnecessary. It is necessary to remind you that the man who was threatened with murder had himself murdered one of our Guardsman, in a quarrel so trivial that a Darkovan boy of twelve would have been ashamed to make more of it than a joke! Then this Terran murderer hid behind his celebrated weaponlessstatus”—even a Terran could not escape that sneer—“to refuse a lawful challenge by the murdered man’s brother! If your men choose to go weaponless, sir, they alone are responsible for their acts.”

Reade Andrusson said, “They do not chooseto go weaponless, Lord Ardais. We are forced by the Compact to deprive them of their accustomed weapons.”

Dyan said, “They are allowed by our laws to carry whatever ethical weapons they choose. They cannot complain of a defenselessness which is their own choice.”

The Legate, turning his eyes consideringly on Dyan, said, ‘Their defenselessness, Lord Ardais, is in obedience to our laws. We have a very distinct bias, which our laws reflect, against carving people up with swords and knives.”

Hastur said harshly, “Is it your contention, sir, that a man is somehow less dead if he is shot down from a safe distance without visible bloodshed? Is death cleaner when it comes to you from a killer safely out of reach of his own death?” Even through my own barriers, his pain was so violent, so palpable that it was like a long wail of anguish; I knew he was thinking of his own son, blown to fragments by smuggled contraband weapons, killed by a man whose face he never saw! So intense was that cry of agony that I saw Danilo, impassive behind Lord Edric, flinch and tighten his hands into white-knuckled fists at his sides; my father looked white and shaken; Regis’ mouth moved and he blinked rapidly, and I wondered how even the Terrans could be unaware of so much pain. But Hastur’s voice was steady, betraying nothing to the aliens. “We banned such coward’s weapons to insure that any man who would kill must see his victim’s blood flow and come into some danger of losing his own, if not at the hands of his victim, at least at the hands of his victim’s family or friends.”

The Legate said, “That episode was settled long ago, Lord Regent, but I remind you we stood ready to prosecute our man for the killing of your Guardsman. We could not, however, expose him to challenges from the dead man’s family one after another, especially when it was abundantly clear that the Guardsman had first provoked the quarrel.”

“Any man who found provocation in such a trivial occurrence should expect to be challenged,” said Dyan, “but your men hide behind your laws and surrender their own personal responsibility! Murder is a private affair and nothing for the laws!”

The Legate surveyed him with what would have been open dislike, had he been a little less controlled. “Our laws are made by agreement and consensus, and whether you approve of them or not, Lord Ardais, they are unlikely to be amended to make murder a matter of private vendetta and individual duels. But this is not the matter at issue.”

I admired his control, the firm way in which he cut Dyan off. My own barriers, thinned by the assault of Hastur’s anguish, were down almost to nothing; I could feel Dyan’s contempt like an audible sneer.

I got my barriers together a little while Hastur silenced Dyan again and reminded him that the incident in question had been settled long since. “Not settled,” Dyan half snarled, “hidden from,” but Hastur firmly cut him off, insisting that there was a more important matter to be settled. By the time I caught up with the discussion again, the Legate was saying:

“Lord Hastur, this is an ethical question, not a legal one at all. We enforce Comyn laws within the jurisdiction of the Comyn. In Caer Donn and the Hellers, where the laws are made by Lord Aldaran, we enforce what laws he requires. If he cannot be bothered to enforce the Compact you value so highly, it is not our business to police it for him—or, my lord, for you.”

Callina Aillard said in her quiet clear voice, “Mr. Ramsay, the Compact is not a law, in your sense, at all. I do not believe either of us quite understands what the other means by law. The Compact has been the ethical basis of Darkovan culture and history for hundreds of years; neither Kermiac of Aldaran nor any other man on Darkover has any right to disregard or disobey it.”

Ramsay said, “You must debate that point with Aldaran himself, my lady. He is not an Empire subject and I have no authority over him. If you want him to keep the Compact, you’ll have to make him keep it.”

Edric Ridenow spoke up for the first time. He said, “It is your responsibility, Ramsay, to enforce the substance of your agreement on our world. Are you intending to shirk that duty because of a quibble?”

“I am not shirking any responsibility which comes properly within the scope of my duties, Lord Serrais,” he said, “but neither is it my duty to settle your disagreements with Aldaran. It seems to me that would be to infringe on the responsibility of the Comyn.”

Dyan opened his mouth again, but Hastur gestured him to silence. “You need not teach me my responsibilities, Mr. Ramsay. The Empire’s agreement with Darkover, and the status of the spaceport, was determined with the Comyn, not with Kermiac of Aldaran. One stipulation of that agreement was enforcement of the Compact; and we intended enforcement, not only in the Domains, but all over Darkover. I dislike using threats, sir, but if you insist upon your right to violate your own agreement, I would be within my authority in closing the spaceport until such time as the agreement is kept in every detail.”

The Legate said, “This, sir, is unreasonable. You have said yourself that the Compact is not a law but an ethical preference. I also dislike using threats, but if you take that course, I am certain that my next orders from the Administrative Center would be to negotiate a new agreement with Kermiac of Aldaran and move the Empire headquarters to Caer Donn Trade City, where we need not trouble Comyn scruples.”

Hastur said bitterly, “You say you are prohibited from taking sides in local political decisions. Do you realize that this would effectively throw all the force of the Terran Empire against the very existence of the Compact?”

“You leave me no choice, sir.”

“You know, don’t you, that such a move would mean war? War not of the Comyn’s making but, the Compact once abandoned, war would inevitably come. We have had no war here for many years. Small skirmishes, yes. But the enforcement of the Compact has kept such battles within reasonable limits. Do you want the responsibility for letting a different kind of war loose?”

“Of course not,” Ramsay said. He was a nontelepath and his emotions were muddy, but I could tell that he was distressed. This distress made me like him just a little more. “Who would?”

“Yet you would hide behind your laws and your orders and your superiors, and let our world be plunged into war again? We had our Ages of Chaos, Ramsay, and the Compact brought them to an end. Does that mean nothing to you?”

The Terran looked straight at Hastur. I had a curious mental picture, a flash picked up from someone in the room, that they were like two massive towers facing one another, as the Comyn Castle and the Terran headquarters faced one another across the valley, gigantic armored figures braced for single combat. The image thinned and vanished and they were just two old men, both powerful, both filled with stubborn integrity, each doing the best for his own side. Ramsay said, “It means a very great deal to me, Lord Hastur. I want to be honest with you. If there was a major war here, it would mean closing and sealing the Trade Cities to be certain of keeping to our law against interference. I don’t want to move the spaceport to Caer Donn. It was built there, a good many years ago. When the Comyn offered us this more convenient spot, down here in the plains at Thendara, we were altogether pleased to abandon the operation at Caer Donn, except for trade and certain transport. The Thendara location has been to our mutual advantage. If we are forced to move back to Caer Donn we would be forced to reschedule all our traffic, rebuild our headquarters back in the mountains where the climate is more difficult for Terrans to tolerate and, above all, rely on inadequate roads and inhospitable countryside. I don’t want to do that, and we will do anything within reason to avoid it.”

Dyan said, “Mr. Ramsay, are you not in command of all the Terrans on Darkover?”

“You have been misinformed, Lord Dyan. I’m a legate, not a dictator. My authority is mostly over spaceport personnel stationed here, and only in matters which for one reason or another supersede that of their individual departments of administration. My major business is to keep order in the Trade City. Furthermore, I have authority from Administration Central to deal with Darkovan citizens through their duly constituted and appointed rulers. I have no authority over any individual Darkovan except for a few civilian employees who choose to hire themselves to us, nor over any individual Empire citizen who comes here to do business, beyond determining that his business is a lawful one for a Class D world. Beyond that, if his business disturbs the peace between Darkover and the Empire, I may intervene. But unless someone appeals to me, I have no authority outside the Trade City,”

It sounded intolerably complicated. How did the Empire manage to get its business done at all? My father had, as yet, said nothing; now he raised his head and said bluntly, “Well we’re appealing to you. These Empire citizens selling blasters in the marketplace of Caer Donn are not doing lawful business for a Class D Closed World, and you know it as well as I do. It’s up to you to do something about it, and do it now. That does come within your responsibility.”

The Legate said, “If the offense were here in Thendara, Lord Alton, I would do so with the greatest pleasure. In Caer Donn I can do nothing unless Lord Kermiac of Aldaran should appeal to me.”

My father looked and sounded angry. He was angry, with a disrupting anger which could have struck the Legate unconscious if he had not been trying hard to control it. “Always the same old story on Terra, what’s your saying, pass the buck? You’re like children playing that game with hot chestnuts, tossing them from one to another and trying not to get burned! I spent eight years on Terra and I never found even one man who would look me in the eye and say, ‘This is my responsibility and I will accept it whatever the consequences.’ ”