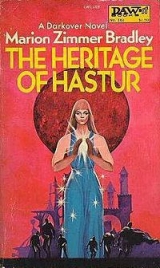

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter FOUR

(Lew Alton’s narrative)

The room was bright with daylight. I had slept for hours on the stone seat by the fireplace, cold and cramped. Marius, barefoot and in his nightshirt, was shaking me. He said, “I heard something on the stairs. Listen!” He ran toward the door; I followed more slowly, as the door was flung open and a pair of Guards carried my father into the room. One of them caught sight of me and said, “Where can we take him, Captain?”

I said, “Bring him in here,” and helped Andres lay him on his own bed. “What happened?” I demanded, staring in dread at his pale, unconscious face.

“He fell down the stone stairs near the Guard hall,” one of the men said. “I’ve been trying to get those stairs fixed all winter; your father could have broken his neck. So could any of us.”

Marius came to the bedside, white and terrified. “Is he dead?”

“Nothing like it, sonny,” said the Guardsman. “I think the Commander’s broken a couple of ribs and done something to his arm and shoulder, but unless he starts vomiting blood later he’ll be all right. I wanted Master Raimon to attend to him down there, but he made us carry him up here.”

Between anger and relief, I bent over him. What a time for him to be hurt. The very first day of Council season! As if my tumbling thoughts could reach him—and perhaps they could—he groaned and opened his eyes. His mouth contracted in a spasm of pain.

“Lew?”

“I’m here, Father.”

“You must take call-over in my place … ”

“Father, no. There are a dozen others with better right.”

His face hardened. I could see, and feel, that he was struggling against intense pain. “Damn you, you’ll go! I’ve fought … whole Council … for years. You’re not going to throw away all my work … because I take a damn silly tumble. You have a right to deputize for me and, damn you, you’re going to!”

His pain tore at me; I was wide open to it. Through the clawing pain I could feel his emotions, fury and a fierce determination, thrusting his will on me. “You will!”

I’m not Alton for nothing. Swiftly I thrust back, fighting his attempt to forceagreement “There’s no need for that, Father. I’m not your puppet!”

“But you’re my son,” he said violently, and it was like a storm, as his will pressed hard on me. “My son and my second in command, and no one, no oneis going to question that!”

His agitation was growing so great that I realized I could not argue further without harming him seriously.

I had to calm him somehow. I met his enraged eyes squarely and said, “There’s no reason to shout at me. I’ll do what you like, for now at least. We’ll argue it out later.”

His eyes fell shut, whether with exhaustion or pain I could not tell. Master Raimon, the hospital-officer of the Guards, came into the room, moving swiftly to his side. I made room for him. Anger, fatigue and loss of sleep made my head pound. Damn him! Father knew perfectly well how I felt! And he didn’t give a damn!

Marius was still standing, frozen, watching in horror as Master Raimon began to cut away my father’s shirt. I saw great purple, blood-darkened bruises before I drew Marius firmly away. “There’s nothing much wrong with him,” I said. “He couldn’t shout that loud if he was dying. Go get dressed, and keep out of the way.”

The child went obediently and I stood in the outer room, rubbing my fists over my face in dismay and confusion. What time was it? How long had I slept? Where was Regis? Where had he gone? In the state he’d been in when he left me, he could have done something desperate! Conflicting loyalties and obligations held me paralyzed. Andres came out of my father’s room and said, “Lew, if you’re going to take call-over you’d better get moving,” and I realized I’d been standing as if my feet had frozen to the floor.

My father had laid a task on me. Yet if Regis had run away, in a mood of suicidal despair, shouldn’t I go after him, too? In any case I would have been on duty this morning. Now it seemed I was to handle it on my own. There were sure to be those who’d question it. Well, it was Father’s right to choose his own deputy, but I was the one who’d have to face their hostility.

I turned to Andres. “Have someone get me something to eat,” I said, “and see if you can find where Father put the staff lists and the roll call, but don’t disturb him. I should bathe and change. Have I time?”

Andres regarded me calmly. “Don’t lose your head. You have what time you need. If you’re in command, they can’t start till you get there. Take the time to make yourself presentable. You ought to lookready to command, even if you don’t feel it.”

He was right, of course; I knew it even while I resented his tone. Andres has a habit of being right. He had been the coridom, chief steward, at Armida since I could remember. He was a Terran and had once been in Spaceforce. I’ve never known where he met my father, or why he left the Empire. My father’s servants had told me the story, that one day he came to Armida and said he was sick of space and Spaceforce, and my father had said, “Throw your blaster away and pledge me to keep the Compact and I’ve work for you at Armida as long as you like.” At first he had been Father’s private secretary, then his personal assistant, finally in charge of his whole household, from my father’s horses and dogs to his sons and foster-daughter. There were times when I felt Andres was the only person alive who completely accepted me for what I was. Bastard, half-caste, it made no difference to Andres.

He added now, “Better for discipline to turn up late than to turn up in a mess and not knowing what you’re doing. Get yourself in order, Lew, and I don’t just mean your uniform. Nothing’s to be gained by rushing off in several directions at once.”

I went off to bathe, eat a hasty breakfast and dress myself suitably to be stared at by a hundred or more officers and Guardsmen, each one of whom would be ready to find fault. Well, let them.

Andres found the staff lists and Guard roster among my father’s belongings; I took them and went down to the Guard hall.

The main Guard hall in Comyn Castle is on one of the lowest levels; behind it lie barracks, stables, armory and parade ground, and before it a barricaded gateway leads down into Thendara. The rest of Comyn Castle leaves me unmoved, but I never looked up at the great fan-lighted windows without a curious swelling in my throat.

I had been fourteen years old, and already aware that because of what I was my life was fragmented and insecure, when my father had first brought me here. Before sending me to my peers, or what he hoped would be my peers—they’d had other ideas—he’d told me of a few of the Altons who had come before us here. For the first and almost the last time, I’d felt a sense of belonging to those old Altons whose names were a roll call of Darkovan history: My grandfather Valdir, who had organized the first fire-beacon system in the Kalghard Hills. DomEsteban Lanart, who a hundred years ago had driven the catmen from the caves of Corresanti. Rafael Lanart-Alton, who had ruled as Regent when Stefan Hastur the Ninth was crowned in his cradle, in the days before the Elhalyn were kings in Thendara.

The Guard hall was an enormous stone-floored, stone-arched room, cobblestones half worn away by the feet of centuries of Guardsmen. The light came curiously, multicolored and splintered, through windows set in before the art of rolling glass was known.

I drew the lists Andres had given me from a pocket and studied them. On the topmost sheet were the names of the first-year cadets. The name of Regis Hastur was at the bottom, evidently added somewhat later than the rest. Damn it where wasRegis? I checked the list of second-year cadets. The name of Octavien Vallonde had been dropped from the rolls. I hadn’t expected to see his name, but it would have relieved my mind.

On the staff list Father had crossed out his own name as commander and written in mine, evidently with his right hand, and with great difficulty. I wished he had saved himself the trouble. Gabriel Lanart-Hastur, Javanne’s husband and my cousin, had replaced me as second-in-command. He should have had the command post. I was no soldier, only a matrix technician, and I fully intended to return to Arilinn at the end of the three-year interval required now by law. Gabriel, though, was a career Guardsman, liked it and was competent. He was an Alton too, and seated on Council. Most Comyn felt he should have been designated Kennard’s heir. Yet we were friends, after a fashion, and I wished he were here today, instead of at Edelweiss waiting for the birth of Javanne’s child.

Father evidently saw no discrepancy. He had been psi technician in Arilinn for over ten years, back in the old days of tower isolation, yet he had been able afterward to return and take command of the Guards without any terrible sense of dissonance. My own inner conflicts evidently were not important, or even comprehensible, to him.

Arms-master again was old Domenic di Asturien, who had been a captain when my father was a cadet of fourteen. He had been my own cadet-master, my first year and was almost the only officer in the Guard who had ever been fair to me.

Cadet-master—I rubbed my eyes and stared at the lists; I must have read it wrong. The words obstinately stayed the same. Cadet-master: Dyan-Gabriel, Lord Ardais.

I groaned aloud. Oh, hell, this had to be one of Father’s perverse jokes. He’s no fool, and only a fool would put a man like Dyan in charge of half-grown boys. Not after the scandal last year. We had managed to keep the scandal from reaching Lord Hastur, and I had believed that even Dyan knew he had gone too far.

Let me be clear about one thing: I don’t like Dyan and he doesn’t approve of me, but he is a brave man and a good soldier, probably the best and most competent officer in the Guards. As for his personal life, no one dares to comment on a Comyn lord’s private amusements.

I learned, long ago, not to listen to gossip. My own birth had been a major scandal for years. But this had been more than gossip. Personally, I think Father had been unwise to hustle the Vallonde boy away home without question or investigation. Part of what he said was true. Octavien was disturbed, unstable, he’d never belonged in the Guards and it was our mistake for ever accepting him as a cadet. But Father had said that the sooner it was hushed up, the quicker the unsavory story would the down. The rumors had never died of course, probably never would.

The room was beginning to fill up with uniformed men.

Dyan came to the dais where the officers were collecting, gave me an unfriendly scowl. No doubt hehad expected to be named as Father’s deputy. Even that would have been better than making him cadet-master.

Damn it, I couldn’tgo along with that. Father’s choice or not.

Dyan’s private life was no one’s affair but his own and I wouldn’t care if he chose to love men, women or goats. He could have as many concubines as a Dry-Towner, and most people would gossip no more and no less. But more scandal in the Guards? Damn it, no! This touched the honor of the Guards, and of the Altons who were in charge of it.

Father had put me in command. This was going to be my first command decision, then.

I signaled for Assembly. One or two late-comers dashed into their places. The seasoned men took their ranks. The cadets, as they had been briefed, stayed in a corner.

Regis wasnt among the cadets. I resented bitterly that I was tied here, but there was no help for it.

I looked them all over and felt them returning the favor. I shut down my telepathic sensitivity as much as I could—it wasn’t easy in this crowd—but I was aware of their surprise, curiosity, disgust, annoyance. It all added up, more or less, to Where the hell is the Commander?Or, worse, What’s old Kennard’s bastard doing up there with the staff?

Finally I got their attention and told them of Kennard’s misfortune. It caused a small flurry of whispers, mutters, comments, most of which I knew it would be unwise to hear. I let them get through most of it, then called them to order again and began the traditional first-day ceremony of call-over.

One by one I read out the name of every Guardsman. Each came forward, repeated a brief formula of loyalty to Comyn and informed me—a serious obligation three hundred years ago, a mere customary formality now—of how many men, trained, armed and outfitted according to custom, he was prepared to put into the field in the event of war. It was a long business. There was a disturbance halfway through it and, escorted by half a dozen servants in Hastur livery, Regis made an entrance. One of the servants gave me a message from Hastur himself, with some kind of excuse or explanation for his lateness.

I realized that I was blisteringly angry. I’d seen Regis desperate, suicidal, ill, prostrated, suffering some unforeseen aftereffect of kirian, even dead—and he walked in casually, upsetting call-over ceremony and discipline. I told him brusquely, “Take your place, cadet,” and dismissed the servants.

He could not have resembled less the boy who had sat by my fire last night, eating stew and pouring out his bitterness. He was wearing full Comyn regalia, badges, high boots, a sky-blue tunic of an elaborate cut. He walked to his place among the cadets, his head held stiffly high. I could sense the fear and shyness in him, but I knew the other cadets would regard it as Comyn arrogance, and he would suffer for it. He looked tired, almost ill, behind the facade of arrogant control. What had happened to him last night? Damn him, I recalled myself with a start, why was I worrying about the heir to Hastur? He hadn’t worried about me, or the fact that if he’d come to harm, I’d have been in trouble!

I finished the parade of loyalty oaths. Dyan leaned toward me and said, “I was in the city with the Council last night. Hastur asked me to explain the situation to the Guards; have I your permission to speak, Captain Montray-Lanart?”

Dyan had never given me my proper title, in or out of the Guard hall. I grimly told myself that the last thing I wanted was his approval. I nodded and he walked to the center of the dais. He looks no more like a typical Comyn lord than I do; his hair is dark, not the traditional red of Comyn, and he is tall, lean, with the six-fingered hands which sometimes turn up in the Ardais and Aillard clans. There is said to be nonhuman blood in the Ardais line. Dyan looks it.

“City Guardsmen of Thendara,” he rapped out, “your commander, Lord Alton, has asked me to review the situation.” His contemptuous look said more plainly than words that I might play at being in command, but he was the one who could explain what was going on.

There seemed, as nearly as I could tell from Dyan’s words, to be a high level of tension in the city, mostly between the Terran Spaceforce and the City Guard. He asked every Guardsman to avoid incidents and to honor the curfew, to remember that the Trade City area had been ceded to the Empire by diplomatic treaty. He reminded us that it was our duty to deal with Darkovan offenders, and to turn Terran ones over to the Empire authorities at once. Well, that was fair enough. Two police forces in one city had to reach some agreements and compromises in living together.

I had to admit Dyan was a good speaker. He managed, however, to convey the impression that the Terrans were so much our natural inferiors, honoring neither the Compact nor the codes of personal honor, that we must take responsbility for them, as all superiors do; that, while we would naturally prefer to treat them with a just contempt, we would be doing Lord Hastur a personal favor by keeping the peace, even against our better judgment. I doubted whether that little speech would really lessen the friction between Terrans and Guardsmen.

I wondered if our opposite numbers in the Trade City, the Legate and his deputies, were laying the law down to Spaceforce this morning. Somehow I doubted it.

Dyan returned to his place and I called the cadets to stand forward. I called the roll of the dozen third-year cadets and the eleven second-year men, wondering if Council meant to fill Octavien Vallonde’s empty place. Then I addressed myself to the first-year cadets, calling them into the center of the room. I decided to skip the usual speech about the proud and ancient organization into which it was a pleasure to welcome them. I’m not Dyan’s equal as a speaker, and I wasn’t going to compete. Father could give them that one when he was well again, or the cadet-master, whoever he was. Not Dyan. Over my dead body.

I confined myself to giving basic facts. After today there would be a full assembly and review every morning after breakfast. The cadets would be kept apart in their own barracks and given instructions until intense drill in basics had made them soldierly enough to take their place in formations and duties. Castle Guard would be set day and night and they would take it in turns from oldest to youngest, recalling that Castle Guard was not menial sentry duty but a privilege claimed by nobles from time out of mind, to guard the Sons of Hastur. And so on.

The final formality—I was glad to reach it, for it was hot in the crowded room by now and the youngest cadets were beginning to fidget—was a formal roll call of first-year cadets. Only Regis and Father’s young protégé Danilo were personally known to me, but some were the younger brothers or sons of men I knew in the Guards. The last name I called was Regis-Rafael, cadet Hastur.

There was a confused silence, just too long. Then down the line of cadets there was a small scuffle and an audible whispered “That’s you, blockhead!” as Danilo poked Regis in the ribs. Regis’ confused voice said “Oh—” Another pause. “Here.”

Damn Regis anyhow. I had begun to hope that thisyear we would get through call-over without having to play this particular humiliating charade. Some cadet, not always a first-year man, invariably forgot to answer properly to his name at call-over. There was a procedure for such occasions which probably went back three dozen generations. From the way in which the other Guardsmen, from veterans to older cadets, were waiting, expectant snickers breaking out, they’d all been waiting—yes, damn them all, and hoping—for this ritual hazing.

Left to myself, I’d have said harshly, “Next time, answer to your name, cadet,” and had a word with him later in private. But if I tried to cheat them all of their fun, they’d probably take it out on Regis anyway. He’d already made himself conspicuous by coming in late and dressed like a prince. I might as well get on with it. Regis would have to get used to worse things than this in the next few weeks.

“Cadet Hastur,” I said with a sigh, “suppose you step forward where we can get a good look at you. Then if you forget your name again, we can all be ready to remind you.”

Regis stepped forward, staring blankly. “You know my name.”

There was a chorus of snickers. Zandru’s hells, was he confused enough to make it worse? I kept my voice cold and even. “It’s my business to know it, cadet, and yours to answer any question put to you by an officer. What is your name, cadet?”

He said, rapid and furious, “Regis-Rafael Felix Alar Hastur-Elhalyn!”

“Well, Regis-Rafael This-that-and-the-other, your name in the Guard hall is cadet Hastur, and I suggest you memorize your name and the proper response to your name, unless you prefer to be addressed as That’s you, blockhead.” Danilo giggled; I glared at him and he subsided. “Cadet Hastur, nobody’s going to call you Lord Regisdown here. How old are you, cadet Hastur?”

“Fifteen,” Regis said. Mentally, I swore again. If he had made the proper response this time—but how could he? No one had warned him—I could have dismissed him. Now I had to play out this farce to the very end. The look of hilarious expectancy on the faces around us infuriated me. But two hundred years of Guardsman tradition were behind it. “Fifteen what, cadet?”

“Fifteen years,” said Regis, biting on the old bait for the unwary. I sighed. Well, the other cadets had a right to their fun. Generations had conditioned them to demand it, and I gave it to them. I said wearily, “Suppose, men, you all tell cadet Hastur how old he is?”

“ Fifteen, sir,” they chorused all together, at the top of their voices. The expected uproar of laughter finally broke loose. I signaled Regis to go back to his place. The murderous glance he sent me could have killed. I didn’t blame him. For days, in fact, until somebody else did something outstandingly stupid, he’d be the butt of the barracks. I knew. I remembered a day several years ago when the name of the unlucky cadet had been Lewis-Kennard, cadet Montray, and I had, perhaps, a better excuse—never having heard my name in that form before. I haven’t heard it since either, because my father had demanded I be allowed to bear his name, Montray-Alton. As usual, he got what he wanted. That was while they were still arguing about my legitimacy. But he used the argument that it was unseemly for a cadet to bear a Terran name in the Guard, even though a bastard legally uses his mother’s name.

Finally the ceremony was over. I should turn the cadets over to the cadet-master and let him take command. No, damn it, I couldn’t do it. Not until I had urged Father to reconsider. I hadn’t wanted to command the Guards, but he had insisted and now, for better or worse, all the Guards, from the youngest cadet to the oldest veteran, were in my care. I was bound to do my best for them and, damn it, my best didn’t include Dyan Ardais as cadet-master!

I beckoned to old Domenic di Asturien. He was an experienced officer, completely trustworthy, exactly the sort of man to be in charge of the young. He had retired from active duty years ago—he was certainly in his eighties—but no one could complain of him. His family was so old that the Comyn themselves were upstarts to him. There was a joke, told in whispers, that he had once spoken of the Hasturs as “the new nobility.”

“Master, the Commander met with an accident this morning, and he has not yet informed me about his choice for cadet-master.” I crushed the staff lists in my hand as if the old man could see Dyan’s name written there and give me the lie direct. “I respectfully request you to take charge of them until he makes his wishes known.”

As I returned to my place, Dyan started to his feet. “You damned young pup, didn’t Kennard tell—” He saw curious eyes on us and dropped his voice. “Why didn’t you speak to me privately about this?”

Damn it. He knew. And I recalled that he was said to be a strong telepath, though he had been refused entry to the towers for unknown reasons, so he knew that I knew. I blanked my mind to him. There are few who can read an Alton when he’s warned. It was a severe breach of courtesy and Comyn ethics that Dyan had done so uninvited. Or was it meant to convey that he didn’t think I deserved Comyn immunity? I said frigidly, trying to be civil, “After I have consulted the Commander, Captain Ardais, I shall make his wishes known to you.”

“Damn you, the Commander has made his wishes known, and you know it,” Dyan said, his mouth hardening into a tight line. There was still time. I could pretend to discover his name on the lists. But eat dirt before the filthy he-whore from the Hellers? I turned away and said to di Asturien, “When you please, Master, you may dismiss your charges.”

“You insolent bastard, I’ll have your hide for this!”

“Bastard I may be,” I said, keeping my voice low, “but I consider it no edifying sight for two captains to quarrel in the hearing of cadets, Captain Ardais,”

He swallowed that. He was soldier enough to know it was true. As I dismissed the men, I reflected on the powerful enemy I had made. Before this, he had disliked me, but he was my father’s friend and anything belonging to a friend he would tolerate, provided it stayed in its place. Now I had gone a long way beyond his rather narrow concept of that place and he would never forgive it.

Well, I could live without his approval. But I had better lose no time in talking to Father. Dyan wouldn’t.

I found him awake and restive, swathed in bandages, his lame leg propped up. He looked haggard and flushed, and I wished I need not trouble him. “Did the call-over go well?”

“Well enough. Danilo made a good appearance,” I said, knowing he’d want to know.

“Regis was added at the last moment. Was he there?” I nodded, and Father asked, “Did Dyan turn up to take charge? He had a sleepless night too, but said he’d be there.”

I stared at him in outrage, finally bursting out, “Father! You can’t be serious! I thought it was a joke! Dyan, as cadet-master?”

“I don’t joke about the Guards,” Father said, his face hard, “and why not Dyan?”

I hesitated, then said, “Must I spell it out for you in full? Have you forgotten last year and the Vallonde youngster?”

“Hysterics,” my father said with a shrug. “You took it more seriously than it deserved. When it came to the point, Octavien refused to undergo laraninterrogation.”

“That only proves he was afraid of you,” I stormed, “nothing more! I’ve known grown men, hardened veterans, break down, accept any punishment, rather than face that ordeal! How many mature adults can undergo telepathic examination at the hands of an Alton? Octavien was fifteen!”

“You’re missing the point, Lew. The fact it, since he did not substantiate the charge, I am not officially required to take notice of it.”

“Did you happen to notice that Dyan never denied it either? He didn’t have the courage to face an Alton and lie, did he?”

Kennard sighed and tried to hoist himself up in bed. I said, “Let me help you,” but he waved me away. “Sit down, Lew, don’t stand over me like a statue of an avenging god! What makes you think he would stoop to lie, or that I have any right to ask for any details of his private life? Is your own life so pure and perfect—”

“Father, whatever I may have done for amusement before I was a grown man is completely beside the point,” I said. “I have never abused authority—”

He said coldly, “It seems you abused it when you ignored my written orders.” His voice hardened. “I told you to sit down! Lew, I don’t owe you any explanations, but since you seem to be upset about this, I’ll make it clear. The world is made as it’s made, not as you or I would like it. Dyan may not be the ideal cadet-master, but he’s asked for this post and I’m not going to refuse him.”

“Why not?” I was more outraged than ever. “Just because he is Lord Ardais, must he be allowed a free hand for any kind of debauchery, corruption, anything he pleases? I don’t care what he does, but does he have to have license to do it in the Guards?” I demanded. “Why?”

“Lew, listen to me. It’s easy to use hard words about anyone who’s less than perfect. They have one for you, or have you forgotten? I’ve listened to it for fifteen years, because I needed you. We need Lord Ardais on Council because he’s a strong man and a strong supporter of Hastur. Have you become so involved with your private world at Arilinn that you don’t remember the real political situation?” I grimaced, but he said, very patient now, “One faction on Council would like to plunge us into war with the Terrans. That’s so unthinkable I needn’t take it seriously, unless this small faction gains support. Another faction wants us to join the Terrans completely, give up our old ways and traditions, give up the Compact, become an Empire colony. That faction’s bigger, and a lot more dangerous to Comyn. I feel that Hastur’s solution, slow change, compromise, above all time, is the only reasonable answer. Dyan is one of the very few men who are willing to throw their weight behind Hastur. Why should we refuse him a position he wants, in return?”

“Then we’re filthy and corrupt,” I raged. “Just to get his support for your political ambitions, you’re willing to bribe a man like Dyan by putting him in charge of half-grown boys?”

My father’s quick rage flared. It had never been turned full on me before. “Do you honestly believe it’s my personal ambition I’m furthering? I ask you, which is more important—the personal ethics of the cadet-master or the future of Darkover and the very survival of the Comyn? No, damn it, you sit there and listen to me! When we need Dyan’s support so badly in Council do you think. I’d quarrel with him over his private behavior?”

I flung back, equally furious, “I wouldn’t give a damn if it washis private behavior! But if there’s another scandal in the Guards, don’t you think the Comyn will suffer? I didn’t ask to command the Guards. I told you I’d rather not. But you wouldn’t listen to my refusal and now you refuse to listen to my best judgment! I tell you, I won’t have Dyan as cadet-master! Not if I’m in command!”

“Oh, yes you will,” said my father in a low and vicious voice. “Do you think I am going to let you defy me?”

“Then, damn it, Father, get someone else to command the Guards! Offer Dyan the command—wouldn’t that satisfy his ambition?”

“But it wouldn’t satisfy me,” he said harshly. ‘I’ve worked for years to put you in this position. If you think I’m going to let you destroy the Domain of Alton by some childish scruples, you’re mistaken. I’m still lord of the Domain and you are oath-bound to take my orders without question! The post of cadet-master is powerful enough to satisfy Dyan, but I’m not going to endanger the rights of the Altons to command. I’m doing it for you, Lew.”

“I wish you’d save your trouble! I don’t want it!”

“You’re in no position to know what you want. Now do as I tell you: go and give Dyan his appointment as cadet-master, or”—he struggled again, ignoring the pain—“I’ll get out of bed and do it myself.”

His anger I could face; his suffering was something else. I struggled between rage and a deadly misgiving. “Father, I have never disobeyed you. But I beg you, I beg you,” I repeated, “to reconsider. You know that no good will come of this.”