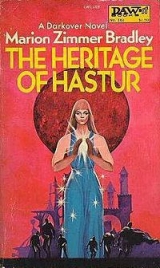

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

“I learned to look after myself at Nevarsin,” Regis said.

He looked warmer now, less tense. “If the Regent is sending for all the Council, I suspect it’s really serious and not just that Grandfather has forgotten me again. That makes me feel better.”

Now I was free to get out of my own wet things. “When you’ve changed, Regis, we’ll have dinner here in front of the fire. I’m not officially on duty till tomorrow morning.”

I went and changed quickly into indoor clothing, slid my feet into fur-lined ankle-boots and looked briefly in on Marius; I found him sitting up in bed, eating hot soup and already half asleep. It was a long ride for a boy his age. I wondered again why Father had subjected him to it

The servants had set up a hot meal before the fire, in front of the old stone seats there. The lights in our part of the castle are the old ones, luminous rock from deep caves which charge with light all day and give off a soft glow all night. Not enough for reading or fine needlework, but plenty for a quiet meal and a comfortable talk by firelight. Regis came back, in dry garments and indoor boots, and I gestured the old steward away. “Go and get your own supper; Lord Regis and I can wait on ourselves.”

I took the covers off the dishes. They had sent in a fried fowl and some vegetable stew. I helped him, saying, “Not very festive, but probably the best they could do at short notice.”

“It’s better than we got on the fire-lines,” Regis said and I grinned. “So you remember that too?”

“How could I forget it? Armida was like home to me. Does Kennard still break his own horses, Lew?”

“No, he’s far too lame,” I said, and wondered again how Father would manage in the coming season. Selfishly, I hoped he would be able to continue in command. It’s hereditary to the Altons, and I was next in line for it. They had learned to tolerate me as his deputy, holding captain’s rank. As commander, I’d have all those battles to fight again.

We talked for a little while about Armida, about horses and hawks, while Regis finished the stew in his bowl. He picked up an apple and went to the fireplace, where a pair of antique swords, used only in the sword-dance now, hung over the mantel. He touched the hilt of one and I asked, “Have you forgotten all your fencing in the monastery, Regis?”

“No, there were some of us who weren’t to be monks, so Father Master gave us leave to practice an hour every day, and an arms-master came to give us lessons.”

Over wine we discussed the state of the roads from Nevarsin.

“Surely you didn’t ride in one day from the monastery?”

“Oh, no. I broke my journey at Edelweiss.”

That was on Alton lands. When Javanne Hastur married Gabriel Lanart, ten years ago, my father had leased them the estate. “Your sister is well, I hope?”

“Well enough, but extremely pregnant just now,” Regis said, “and Javanne’s done a ridiculous thing. It made sense to call their first son Rafael, after her father and mine. And the second, of course, is the younger Gabriel. But when she named the third Mikhail, she made the whole thing absurd. I believe she’s praying frantically for a girl this time!”

I laughed. By all accounts the “Lanart angels” should be named for the archfiends, not the archangels; and why should a Hastur seek names from cristoforomythology? “Well, she and Gabriel have sons enough.”

“True. I am sure my grandfather is annoyed that she should have so many sons, and cannot give them Domain-right in Hastur. And I should have told Kennard; her husband will be here in a few days to take his place in the Guard. He would have ridden with me, but with Javanne so near to her time, he got leave to remain with her till she is delivered.”

I nodded; of course he would stay. Gabriel Lanart was a minor noble of the Alton Domain, a kinsman of our own, and a telepath. Of course he would follow the custom of the Domains, that a man shares with his child’s mother the ordeal of birth, staying in rapport with her until the child is born and all is well. Well, we could spare him for a few days. A good man, Gabriel.

“Dyan seemed to take it for granted that you would be in the cadets this year,” I said.

“I don’t know if I’ll have a choice. Did you?”

I hadn’t, of course. But that the heir to Hastur, of all people, should question it—that made me uneasy.

Regis sat on the stone bench, restlessly scuffing his felt ankle-boots on the floor, “Lew, you’re part Terran and yet you’re Comyn. Do you feel as if you belonged to us? Or to the Terrans?”

A disturbing question, an outrageous, question, and one I had never dared ask myself. I felt angry at him for speaking it, as if taunting me with what I was. Here I was an alien; among the Terrans, a freak, a mutant, a telepath. I said at last, bitterly, “I’ve never belonged anywhere. Except, perhaps, at Arilinn.”

Regis raised his face, and I was startled at the sudden anguish there. “Lew, what does it feel like to have laran?”

I stared at him, disconcerted. The question touched off another memory. That summer at Armida, in his twelfth year. Because of his age, and because there was no one else, it had fallen to me to answer certain questions usually left to fathers or elder brothers, to instruct him in certain facts proper to adolescents. He bad blurted those questions out, too, with the same kind of half-embarrassed urgency, and I’d found it just as difficult to answer them. There are some things it’s almost impossible to discuss with someone who hasn’t shared the experience. I said at last, slowly, “I hardly know how to answer. I’ve had it so long, it would be harder to imagine what it feels like notto have laran.”

“Were you born with it, then?”

“No, no, of course not. But when I was ten, or eleven, I began to be aware of what people were feeling. Or thinking. Later my father found out—proved to them—that I had the Alton gift, and that’s rare even—” I set my teeth and said it, “even in legitimate sons. After that, they couldn’t deny me Comyn rights.”

“Does it always come so early? Ten, eleven?”

“Have you never been tested? I was almost certain … ” I felt a little confused. At least once during the shared fears of that last season together, on the fire-lines, I had touched his mind, sensed that he had the gift of our caste. But he had been very young then. And the Alton gift is forced rapport, even with nontelepaths.

“Once,” said Regis, “about three years ago. The leronissaid I had the potential, as far as she could tell, but she could not reach it.”

I wondered if that was why the Regent had sent him to Nevarsin: either hoping that discipline, silence and isolation would develop his laran, which sometimes happened, or trying to conceal his disappointment in his heir.

“You’re a licensed matrix mechanic, aren’t you, Lew? What’s that like?”

This I could answer. “You know what a matrix is: a jewel stone that amplifies the resonances of the brain and transmutes psi power into energy. For handling major forces, it demands a group of linked minds, usually in a tower circle.”

“I know what a matrix is,” he said. “They gave me one when I was tested.” He showed it to me, hung, as most of us carried them, in a small silk-lined leather bag about his neck. “I’ve never used it, or even looked at it again. In the old days, I know, they made these mind-links through the Keepers. They don’t have Keepers any more, do they?”

“Not in the old sense,” I said, “although the woman who works centerpolar in the matrix circles is still called a Keeper. In my father’s time they discovered that a Keeper could function, except at the very highest levels, without all the old taboos and terrible training, the sacrifice, isolation, special cloistering. His foster-sister Cleindori was the first to break the tradition, and they don’t train Keepers in the old way any more. It’s too difficult and dangerous, and it’s not fair to ask anyone to give up their whole lives to it any more. Now everyone spends three years or less at Arilinn, and then spends the same amount of time outside, so that they can learn to live normal lives.” I was silent, thinking of my circle at Arilinn, now scattered to their homes and estates. I had been happy there, useful, accepted. Competent. Some day I would go back to this work again, in the relays.

“What it’s like,” I continued, “it’s—it’s intimate. You’re completely open to the members of your circle. Your thoughts, your very feelings affect them, and you’re wholly vulnerable to theirs. It’s more than the closeness of blood kin. It’s not exactly love. It’s not sexual desire. It’s like—like living with your skin off. Twice as tender to everything. It’s not like anything else.”

His eyes were rapt. I said harshly, “Don’t romanticize it. It can be wonderful, yes. But it can be sheer hell. Or both at once. You learn to keep your distance, just to survive.”

Through the haze of his feelings I could pick up just a fraction of his thoughts. I was trying to keep my awareness of him as low as possible. He was, damn it, too vulnerable. He was feeling forgotten, rejected, alone. I couldn’t help picking it up. But a boy his age would think it prying.

“Lew, the Alton gift is the ability to force rapport. If I do have laran, could you open it up, make it function?”

I looked at him in dismay. “You fool. Don’t you know I could kill you that way?”

“Without laran, my life doesn’t amount to much.” He was as taut as a strung bow. Try as I might, I could not shut out the terrible hunger in him to be part of the only world he knew, not to be so desperately deprived of his heritage.

It was my own hunger. I had felt it, it seemed, since my birth. Yet nine months before my birth, my father had made it impossible for me to belong wholly to his world and mine.

I faced the torture of knowing that, deeply as I loved my father, I hated him, too. Hated him for making me bastard, half-caste, alien, belonging nowhere. I clenched my fists, looking away from Regis. He had what I could never have. He belonged, full Comyn, by blood and law, legitimate—

And yet he was suffering, as much as I was. Would I give up laranto be legitimate, accepted, belonging?

“Lew, will you try at least?”

“Regis, if I killed you, I’d be guilty of murder.” His face turned white. “Frightened? Good. It’s an insane idea. Give it up, Regis. Only a catalyst telepath can ever do it safely and I’m not one. As far as I know, there are no catalyst telepaths alive now. Let well enough alone.”

Regis shook his head. He said, forcing the words through a dry mouth, “Lew, when I was twelve years old you called me bredu. There is no one else, no one I can ask for this. I don’t care if it kills me. I have heard”—he swallowed hard—“that bredinhave an obligation, one to the other. Was it only an idle word, Lew?”

“It was no idle word, bredu,” I muttered, wrung with his pain, “but we were children then. And this is no child’s play, Regis, it’s your life.”

“Do you think I don’t know that?” He was stammering. “It is my life. At least it can make the difference in what my life will be.” His voice broke. “ Bredu… ” he said again and was silent, and I knew it was because he could not go on without weeping.

The appeal left me defenseless to him. Try as I might to stay aloof, that helpless, choked “ Bredu… ” had broken my last defense. I knew I was going to do what he wanted. “I can’t do what was done to me,” I told him. “That’s a specific test for the Alton gift—forcing rapport—and only a full Alton can live through it. My father tried it, just once, with my full knowledge that it might very well kill me, and only for about thirty seconds. If the gift hadn’t bred true, I’d have died. The fact that I didn’t die was the only way he could think of to prove to Council that they could not refuse to accept me.” My voice wavered. Even after almost ten years, I didn’t like thinking about it. “Your blood, or your paternity, isn’t in question. You don’t need to take that kind of risk.”

“ Youwere willing to take it.”

I had been. Time slid out of focus, and once again I stood before my father, his hands touching my temples, living again that memory of terror, that searing agony. I had been willing because I had shared my father’s anguish, the terrible need in him to know I was his true son—the knowledge that if he could not force Council to accept me as his son, life alone was worth nothing. I would rather have died, just then, than live to face the knowledge of failure.

Memory receded. I looked into Regis’ eyes.

“I’ll do what I can. I can test you, as I was tested at Arilinn. But don’t expect too much. I’m not a leronis, only a technician.”

I drew a long breath. “Show me your matrix.”

He fumbled with the strings at the neck, tipped the stone out in his palm, held it out to me. That told me as much as I needed to know. The lights in the small jewel were dim, inactive. If he had worn it for three years and his laranwas active, he would have rough-keyed it even without knowing it. The first test had failed, then.

As a final test, with excruciating care, I laid a fingertip against the stone; he did not flinch. I signaled to him to put it away, loosened the neck of the case of my own. I laid my matrix, still wrapped in the insulating silk, in the palm of my hand, then bared it carefully.

“Look into this. No, don’t touch it,” I warned, with a drawn breath. “Never touch a keyed matrix; you could throw me into shock. Just look into it.”

Regis bent, focused with motionless intensity on the tiny ribbons of moving light inside the jewel. At last he looked away. Another bad sign. Even a latent telepath should have had enough energon patterns disrupted inside his brain to show somereaction: sickness, nausea, causeless euphoria. I asked cautiously, not wanting to suggest anything to him, “How do you feel?”

“I’m not sure,” he said uneasily. “It hurt my eyes.”

Then he had at least latent laran. Arousing it, though, might be a difficult and painful business. Perhaps a catalyst telepath could have roused it. They had been bred for that work, in the days when Comyn did complex and life-shattering work in the higher-level matrices. I’d never known one. Perhaps the set of genes was extinct

Just the same, as a latent he deserved further testing. I knew he had the potential. I had known it when he was twelve years old.

“Did the leronistest you with kirian?” I asked.

“She gave me a little. A few drops.”

“What happened?”

“It made me sick,” Regis said, “dizzy. Flashing colors in front of my eyes. She said I was probably too young for much reaction, that in some people, larandeveloped later.”

I thought that over. Kirianis used to lower the resistance against telepathic contact; it’s used in treating empaths and other psi technicians who, without much natural telepathic gift, must work directly with other telepaths. It can sometimes ease fear or deliberate resistance to telepathic contact. It can also be used, with great care, to treat threshold sickness—that curious psychic upheaval which often seizes on young telepaths at adolescence.

Well, Regis seemed young for his age. He might simply be developing the gift late. But it rarely came as late as this. Damn it I’d been positive. Had some event at Nevarsin, some emotional shock, made him block awareness of it?

“I could try that again,” I said tentatively. The kirianmight actually trigger latent telepathy; or perhaps, under its influence, I could reach his mind, without hurting him too much, and find out if he was deliberately blocking awareness of laran. It did happen, sometimes.

I didn’t like using kirian. But a small dose couldn’t do much worse than make him sick, or leave him with a bad hangover. And I had the distinct and not very pleasant feeling that if I cut off his hopes now, he might do something desperate. I didn’t like the way he was looking at me, taut as a bowstring, and shaking, not much, but from head to foot. His voice cracked a little as he said, “I’ll try.” All too clearly, what I heard was, I’ll try anything.

I went to my room for it, already berating myself for agreeing to this lunatic experiment. It simply meant too much to him. I weighed the possibility of giving him a sedative dose, one that would knock him out or keep him safely drugged and drowsy till morning. But kirianis too unpredictable. The dose which puts one person to sleep like a baby at the breast may turn another into a frenzied berserker, raging and hallucinating. Anyway, I’d promised; I wouldn’t deceive him now. I’d play it safe though, give him the same cautious minimal dose we used with strange psi technicians at Arilinn. This much kiriancouldn’t hurt him.

I measured him a careful few drops in a wineglass. He swallowed it, grimacing at the taste, and sat down on one of the stone benches. After a minute he covered his eyes. I watched carefully. One of the first signs was the dilation of the pupils of the eyes. After a few minutes he began to tremble, leaning against the back of the seat as if he feared he might fall. His hands were icy cold. I took his wrist lightly in my fingers. Normally I hate touching people; telepaths do, except in close intimacy. At the touch he looked up and whispered, “Why are you angry, Lew?”

Angry? Did he interpret my fear for him as anger? I said, “Not angry, only worried about you. Kirianisn’t anything to play with. I’m going to try and touch you now. Don’t fight me if you can help it.”

I gently reached for contact with his mind. I wouldn’t use the matrix for this; under kirianI might probe too far and damage him. I first sensed sickness and confusion—that was the drug, no more—then a deathly weariness and physical tension, probably from the long ride, and finally an overwhelming sense of desolation and loneliness, which made me want to turn away from his despair. Hesitantly, I risked a somewhat deeper contact.

And met a perfect, locked defense, a blank wall. After a moment, I probed sharply. The Alton gift was forced rapport, even with nontelepaths. He wanted this, and if I could give it to him, then he could probably endure being hurt. He moaned and moved his head as if I was hurting him. Probably I was. The emotions were still blurring everything. Yes, he had laranpotential. But he’d blocked it. Completely.

I waited a moment and considered. It’s not so uncommon; some telepaths live all their lives that way. There’s no reason they shouldn’t. Telepathy, as I told him, is far from an un-mixed blessing. But occasionally it yielded to a slow, patient unraveling. I retreated to the outer layer of his consciousness again and asked, not in words, What is it you’re afraid to know, Regis? Don’t block it. Try to remember what it is you couldn’t bear to know. There was a time when you could do this knowingly. Try to remember …

It was the wrong thing. He had received my thought; I felt the response to it—a clamshell snapping rigidly shut, a sensitive plant closing its leaves. He wrenched his hands roughly from mine, covering his eyes again. He muttered, “My head hurts. I’m sick, I’m so sick … ”

I had to withdraw. He had effectively shut me out. Possibly a skilled, highly-trained Keeper could have forced her way through the resistance without killing him. But I couldn’t force it. I might have battered down the barrier, forced him to face whatever it was he’d buried, but he might very well crack completely, and whether he could ever be put together again was a very doubtful point.

I wondered if he understood that he had done this to himself. Facing that kind of knowledge was a terribly painful process. At the time, building that barrier must have seemed the only way to save his sanity, even if it meant paying the agonizing price of cutting off his entire psi potential with it. My own Keeper had once explained it to me with the example of the creature who, helplessly caught in a trap, gnaws off the trapped foot, choosing maiming to death. Sometimes there were layers and layers of such barricades.

The barrier, or inhibition, might some day dissolve of itself, releasing his potential. Time and maturity could do a lot. It might be that some day, in the deep intimacy of love, he would find himself free of it. Or—I faced this too—it might be that this barrier was genuinely necessary to his life and sanity, in which case it would endure forever, or, if it were somehow broken down, there would not be enough left of him to go on living.

A catalyst telepath probably could have reached him. But in these days, due to inbreeding, indiscriminate marriages with nontelepaths and the disappearance of the old means of stimulating these gifts, the various Comyn psi powers no longer bred true. I was living proof that the Alton gift did sometimes appear in pure form. But as a general thing, no one could sort out the tangle of gifts. The Hastur gift, whatever that was—even at Arilinn they didn’t tell me—is just as likely to appear in the Aillard or Elhalyn Domains. Catalyst telepathy was once an Ardais gift. Dyan certainly wasn’t one! As far as I knew, there were none left alive.

It seemed a long time later that Regis stirred again, rubbing his forehead; then he opened his eyes, still with that terrible eagerness. The drug was still in his system—it wouldn’t wear off completely for hours—but he was beginning to have brief intervals free of it. His unspoken question was perfectly clear. I had to shake my head, regretfully.

“I’m sorry, Regis.”

I hope I never again see such despair in a young face. If he had been twelve years old, I would have taken him in my arms and tried to comfort him. But he was not a child now, and neither was I. His taut, desperate face kept me at arm’s length.

“Regis, listen to me,” I said quietly. “For what it’s worth, the laranis there. You have the potential, which means, at the very least, you’re carrying the gene, your children will have it.” I hesitated, not wanting to hurt him further, by telling him straightforwardly that he had made the barrier himself. Why hurt him that way?

I said, “I did my best, bredu. But I couldn’t reach it, the barriers were too strong. Bredu, don’t look at me like that,” I pleaded, “I can’t bear it, to see you looking at me that way.”

His voice was almost inaudible. “I know. You did your best.”

Had I really? I was struck with doubt I felt sick with the force of his misery. I tried to take his hands again, forcing myself to meet his pain head-on, not flinch from it But he pulled away from me, and I let it go.

“Regis, listen to me. It doesn’t matter. Perhaps in the days of the Keepers, it was a terrible tragedy for a Hastur to be without laran. But the world is changing. The Comyn is changing. You’ll find other strengths.”

I felt the futility of the words even as I spoke them. What must it be like, to live without laran? Like being without sight, hearing … but, never having known it, he must not be allowed to suffer its loss.

“Regis, you have so much else to give. To your family, to the Domains, to our world. And your children will have it—” I took his hands again in mine, trying to comfort him, but he cracked.

“Zandru’s hells, stopit,” he said, and wrenched his hands roughly away again. He caught up his cloak, which lay on the stone seat, and ran out of the room.

I stood frozen in the shock of his violence, then, in horror, ran after him. Gods! Drugged, sick, desperate, he couldn’t be allowed to run off that way! He needed to be watched, cared for, comforted—but I wasn’t in time. When I reached the stairs, he had already disappeared into the labyrinthine corridors of that wing, and I lost him.

I called and hunted for hours before, reeling with fatigue since I, too, had been riding for days, I gave up finally and went back to my rooms. I couldn’t spend the whole night storming all over Comyn Castle, shouting his name! I couldn’t force my way into the Regent’s suite and demand to know if he was there! There were limits to what Kennard Alton’s bastard son could do. I suspected I’d already exceeded them. I could only hope desperately that the kirianwould make him sleepy, or wear off with fatigue, and he would come back to rest or make his way to the Hastur apartments and sleep there.

I waited for hours and saw the sun rise, blood-red in the mists hanging over the Terran spaceport, before, cramped and cold, I fell asleep on the stone bench by the fireplace.

But Regis did not return.

previous | Table of Contents | next