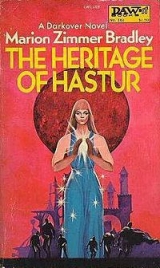

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

“I must go,” he said to his sister. “Send for my horse and someone to open the gates without noise.” As they waited together in the gateway, he said, “If I do not return—”

“Speak no ill-omen!” she said quickly.

“Javanne, do you have the Hastur gift?”

“I do not know,” she said. “None knows till it is wakened by one who holds it. We had always thought that you had no laran… ”

He nodded grimly. He had grown up with that, and even now it was too sore a wound to touch.

She said, “A day will came when you must go to Grandfather. who holds it to waken in his heir, and ask for the gift.

“Then, and only then, you will know what it is. I do not know myself,” she said. “Only if you had died before you were declared a man, or before you had fathered a son, it would have been wakened in me so that, before my own death, I might pass it to one of my sons.”

And so it might pass, still. He heard the soft clop-clop-clopping of hooves in the dark. He prepared to mount, turned back a moment and took Javanne briefly in his arms. She was crying. He blinked tears from his own eyes. He whispered, “Be good to my son, darling.” What more could he say? She kissed him quickly in the dark and said, “Say you’ll come back, brother. Don’t say anything else.” Without waiting for another word, she wrenched herself free of him and ran back into the dark house.

The gates of Edelweiss swung shut behind him. Regis was alone The night was dark, fog-shrouded. He fastened his cloak about his throat, touching the small pouch where the matrix lay. Even through the insulation he could feel it, though no other could have, a small live thing, throbbing … He was alone with it, under the small horn of moon lowering behind the distant hills. Soon even that small light would be gone.

He braced himself, murmured to his horse, straightened his back and rode away northward, on the first step of his unknown journey.

previous | Table of Contents | next

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter SIXTEEN

(Lew Alton’s narrative)

Until the day I die, I am sure I shall return in dreams to that first joyous time at Aldaran.

In my dreams, everything that came after has been wiped out, all the pain and terror, and I remember only that time when we were all together and I was happy, wholly happy for the first and last time in my life. In those dreams Thyra moves with all her strange wild beauty, but gentle and subdued, as she was during those days, tender and pliant and loving. Beltran is there, too, with his fire and the enthusiasm of the dream from which we had all taken the spark, my friend, almost my brother. Kadarin is always there, and in my dreams he is always smiling, kind, a rock of strength bearing us all up when we faltered. And Rafe, the son I shall never have, always beside me, his eyes lifted to mine.

And Marjorie.

Marjorie is always with me in those dreams. But there is nothing I can say about Marjorie. Only that we were together and in love, and as yet the fear was only a little, little shadow, like a breath of chill from a glacier not yet in sight. I wanted her, of course, and I resented the fact that I could not touch her even in the most casual way. But it wasn’t as bad as I had feared. Psi work uses up so much energy and strength that there’s nothing much left. I was with her every waking moment and it was enough. Almostenough. And we could wait for the rest.

I wanted a well-trained team, so I worked with them day by day, trying to shape us all together into a functioning circle which could work together, precisely tuned. As yet we were working with our small matrices; before we joined together to open and call forth the power of the big one, we must be absolutely attuned to one another, with no hidden weaknesses. I would have felt safer with a circle of six or eight, as at Arilinn. Five is a small circle, even with Beltran working outside as a psi monitor. But Thyra and Kadarin were stronger than most of us at Arilinn—I knew they were both stronger than I, though I had more skill and training—and Marjorie was fantastically talented. Even at Arilinn, they would have chosen her the first day as a potential Keeper.

Deep warmth and affection, even love, had sprung up among all of us with the gradual blending of our minds. It was always like this, in the building of a circle. It was closer than family intimacy, closer than sexual love. It was a sort of blending, as if we all melted into one another, each of us contributing something special, individual and unique, and somehow all of us together becoming more than the sum of us.

But the others were growing impatient. It was Thyra who finally voiced what they were all wanting to know.

“When do we begin to work with the Sharra matrix? We’re as ready as we’ll ever be.”

I demurred. “I’d hoped to find others to work with us; I’m not sure we can operate a ninth-level matrix alone.”

Rafe asked, “What’s a ninth-level matrix?”

“In general,” I said dryly, “it’s a matrix not safe to handle with less than nine workers. And that’s with a good, fully trained Keeper.”

Kadarin said, “I told you we should have chosen Thyra.”

“I won’t argue with you about it. Thyra is a very strong telepath; she is an excellent technician and mechanic. But no Keeper.”

Thyra asked, “Exactly how does a Keeper differ from any other telepath?”

I struggled to put it into language she could understand. “A Keeper is the central control in the circle; you’ve all seen that. She holds together the forces. Do you know what energons are?”

Only Rafe ventured to ask, “Are they the little wavy things that I can’t quite see when I look into the matrix?”

Actually that was a very good answer. I said, “They’re a purely theoretical name for something nobody’s sure really exists. It’s been postulated that the part of the brain which controls psi forces gives off a certain type of vibration which we call energons. We can describe what they do, though we can’t really describe them. These, when directed and focused through a matrix—I showed you—become immensely amplified, with the matrix acting as a transformer. It is the amplifiedenergons which transform energy. Well, in a matrix circle, it is the Keeper who receives the flow of energons from all members of the circle and weaves them all into a single focused beam, and this, the focused beam, is what goes through the large matrix.”

“Why are Keepers always women?”

“They aren’t. There have been male Keepers, powerful ones, and other men who have taken a Keeper’s place. I can do it myself. But women have more positive energon flows, and they begin to generate them younger and keep them longer.”

“You explained why a Keeper has to be chaste,” Marjorie said, “but I still don’t understand it.”

Kadarin said, “That’s because it’s superstitious drivel. There’s nothing to understand; it’s gibberish.”

“In the old days,” I said, “when the really enormous matrix screens were made, the big synthetic ones, the Keepers were virgins, trained from early childhood and conditioned in ways you wouldn’t believe. You know how close a matrix circle is.” I looked around at them, savoring the closeness. “In those days a Keeper had to learn to be part of the circle and yet completely, completelyapart from it.”

Marjorie said, “I should think they’d have gone mad.”

“A good many of them did. Even now, most of the women who work as Keepers give it up after a year or two. It’s too difficult and frustrating. The Keepers at the towers aren’t required to be virgins any more. But while they are working as Keepers, they stay strictly chaste.”

“It sounds like nonsense,” Thyra said.

“Not a bit of it,” I said. “The Keeper takes and channels all that energy from all of you. No one who has ever handled these very high energy-flows wants to take the slightest chance of short-circuiting them through her own body. It would be like getting in the way of a lightning-bolt.” I held out the scar again. “A three-second backflow did that to me. Well, then. In the body there are clusters of nerve fibers which control the energy flows. The trouble is that the same nerve clusters carry two kinds of energy; they carry the psi flows, the energons which carry power to the brain; they also carry the sexual messages and energies. This is why some telepaths get threshold sickness when they’re in their teens: the two kinds of energy, sexual energies and laran, are both wakening at once. If they aren’t properly handled, you can get an overload, sometimes a killer overload, because each stimulates the other and you get a circular feedback.”

Beltran asked, “Is that why—”

I nodded, knowing what he was going to ask. “Whenever there’s an energon drain, as in concentrated matrix work, there’s some nerve overloading. Your energies are depleted—have you noticed how we’ve all been eating?—and your sexual energies are at a low ebb, too. The major side effect for men is temporary impotence.” I repeated, smiling reassuringly at Beltran, “ Temporaryimpotence. Nothing to worry about, but it does take some getting used to. By the way, if you ever find you can’t eat, come to one of us right away for monitoring; that can be an early-warning signal that your energy flows are out of order.”

“Monitoring. That’s what you’re teaching me to do, then?” Beltran asked, and I nodded. “That’s right. Even if you can’t link into the circle, we can use you as a psi monitor.” I knew he was still resentful about this. He knew enough by now to know it was the work usually done by the youngest and least skilled in the circle. The worst of it was that unless he could stop projecting this resentment, we couldn’t even use him near the circle. Not even as a psi monitor. There are few things that can disrupt a circle faster than uncontrolled resentments.

I said, “In a sense, the Keeper and the psi monitor are at the two ends of a circle—and almost equally important.” This was true. “Often enough, the life of the Keeper is in the hands of the monitor, because she has no energy to waste in watching over her own body.”

Beltran grinned ruefully, but he grinned. “So Marjorie is the head and I’m the old cow’s tail!”

“By no means. Rather she’s at the top of the ladder and you’re on the ground holding it steady. You’re the lifeline.” I remembered suddenly that we had come far astray from the subject, and said, “With a Keeper, if the nerve channels are not completelyclear they can overload, and the Keeper will burn up like a torch. So while the nerve channels are being used to carry these tremendous energy overloads, they cannot be used to carry any other form of energy. And only complete chastity can keep the channels clear enough.”

Marjorie said, “I can feel the channels all the time now. Even when I’m not working in the matrices. Even when I’m asleep.”

“Good.” That meant she was functioning as a Keeper now. Beltran looked at her with half shut eyes and said, “I can see them, almost.”

“That’s good, too,” I said. “A time will come when you’ll be able to sense the energy flows from across the room—or a mile away—and pinpoint any backflows or energy disruptions in any of us.”

I deliberately changed the subject. I asked, “Precisely what do we want to do with the Sharra matrix, Beltran?”

“You know my plans.”

“Plans, yes, precisely what do you want to do first? I know that in the end you want to prove that a matrix this size can power a starship—”

“Can it?” Marjorie asked.

“A matrix this size, love, could bring one of the smaller moons right down out of its orbit, if we were insane enough to try. It would, of course, destroy Darkover along with it. Powering a starship with one might be possible, but we can’t try here. Among other reasons, we haven’t got a starship yet. We need a smaller project to experiment with, to learn to direct and focus the force. This force is fire-powered, so we also need a place to work where, if we lose control for a few seconds, we won’t burn up a thousand leagues of forest.”

I saw Beltran shudder. He was mountain bred too, and shared with all Darkovans the fear of forest fire. “Father has four Terran aircraft, two light planes and two helicopters. One helicopter is away in the lowlands, but would the other be suitable for experiment?”

I considered. “The explosive fuel should be removed first,” I said, “so if anything doesgo wrong it won’t burn. Otherwise a helicopter might be ideal, experimenting with the rotors to lift and power and control it. It’s a question of developing control and precision. You wouldn’t put Rafe, here, to riding your fastest racehorse.”

Rafe said shyly, “Lew, you said we need other telepaths. Lord Kermiac … didn’t he train matrix mechanics before any of us were born? Why isn’t he one of us?”

True. He had trained Desideria and trained her so well that she could use the Sharra matrix—

“And she used it alone,” said Kadarin, picking up my thoughts. “So why does it worry you that we are so few?”

“She didn’t use it alone,” I said. “She had fifty to a hundred believers focusing their raw emotion on the stone. More, she did not try to control it or focus it. She used it as a weapon, rather, she let it use her.” I felt a sudden cold shudder of fear, as if every hair on my body were prickling and standing erect. I cut off the thought. I was tower-trained. I had no will to wield it for power. I was sworn.

“As for Kermiac,” I said, “he is old, past controlling a matrix. I wouldn’t risk it, Rafe.”

Beltran grew angry. “Damn it, you might have the courtesy to ask him!”

That seemed fair enough, when I weighed the experience he must have had against his age and weakness. “Ask him, if you will. But don’t press him. Let him make his own choice freely.”

“He will not,” Marjorie said. She colored as we all turned on her. “I thought it was my place, as Keeper, to ask him. He called it to my mind that he would not even teach me. He said a circle was only as strong as the weakest person in it, and he would endanger all our lives.”

I felt both disappointed and relieved. Disappointed because I would have welcomed a chance to join him in that special bond that comes only among the members of a circle, to feel myself truly one of his kin. Relieved, because what he had told Marjorie was true, and we all knew it.

Thyra said rebelliously, “Does he understand how much we need him? Isn’t it worth some risk?”

I would have risked the hazards to us, not those to him. At Arilinn they recommended gradual relinquishing of the work after early middle age, as vitality lessened.

“Always Arilinn,” Thyra said impatiently, as if I had spoken aloud. “Do they train them there to be cowards?”

I turned on her, tensing myself against that sudden inner anger which Thyra could rouse in me so easily. Then, sternly controlling myself before Marjorie or the others could be caught up in the whirlpool emotion which swirled and raced between Thyra and me, I said, “One thing they doteach us, Thyra, is to be honest with ourselves and each other.” I held out my hands to her. If she had been taught at Arilinn she would have known already that anger was all too often a concealment for less permissible emotions. “Are you ready to be so honest with me?”

Reluctantly, she took my extended hand between her own. I fought to keep my barriers down, not to barricade myself against her. She was trembling, and I knew this was a new and distressing experience to her, that no man except Kadarin, who had been her lover for so long, had ever stirred her senses. I thought, for a moment, she would cry. It would have been better if she had, but she bit her lip and stared at me, defiant. She whispered, half-aloud, “Don’t—”

I broke the trembling rapport, knowing I could not force Thyra, as I would have had to do at Arilinn, to go into this all the way and confront what she refused to see. I couldn’t. Not before Marjorie.

It was not cowardice, I told myself fiercely. We were all kinsmen and kinswomen. There was simply no need.

I said, changing the subject quickly, “We can try keying the Sharra matrix tomorrow, if you want. Have you explained to your father, Beltran, that we will need an isolated place to work, and asked leave to use the helicopter?”

“I will ask him tonight, when we are at dinner,” Beltran promised.

After dinner, when we were all seated in the little private study we had made our center, he came to us and told us permission had been given, that we could use the old airstrip. We talked little that night, each thinking his or her own thoughts. I was thinking that it had certainly cost Kadarin a lot to turn the matrix over to me. All along, he had expected that he and Beltran would be wholly in charge of this work, that I would be only a helper, lending skill but with no force to decisions. Beltran probably still resented my taking charge, and his inability to be part of the circle was most likely the bitterest dose he had ever had to swallow.

Marjorie was a little apart from us all, the heartbreaking isolation of a Keeper having already begun to slip down over her, forcing her away from the rest. I hated myself for having condemned her to this. With one part of myself I wanted to smash it all and take her into my arms. Maybe Kadarin was right, maybe the chastity of a Keeper was the stupidest of Comyn superstitions, and Marjorie and I were going through all this hell unnecessarily.

I let myself drift out of focus, trying to see ahead to a day when we would be free to love one another. And strangely, though my life was here and I felt I had wholly renounced my allegiance to Comyn, I still tried to see myself breaking the news to my father.

I came up to ordinary awareness and saw that Rafe was asleep on the hearth. Someone should wake him and send him to bed. Was this work too strenuous for a boy his age? He should be playing with button-sized matrices, not working seriously in a circle like this!

My eyes dwelt longest, with a cruel envy, on Kadarin and Thyra, side by side on the hearthrug, gazing into the fire. No prohibition lay between them; even separated, they had each other. I saw Marjorie’s eyes come to rest on them, with the same remote sadness. That, at least, we could share … and for now it was all we could share.

I turned my hand over and looked with detached sorrow at the mark tattooed on my right wrist, the seal of Comyn. The sign that I was laranheir to a Domain. My father had sworn for me, before that mark was set there, for service to Comyn, loyalty to my people.

I looked at the scar from my first year at Arilinn. It ached whenever I was doing matrix work like this; it ached now. That, not the tattoo mark of my Domain, was the real sign of my loyalty to Darkover. And now I was working for a great rebirth of knowledge and wisdom to benefit all our world. I was breaking the law of Arilinn by working with untrained telepaths, unmonitored matrices. Breaking their letter, perhaps, to restore their spirit all over Darkover!

When, yawning wearily, Rafe and the women went their way to bed, I detained Kadarin for a moment. “One thing I have to know. Are you and Thyra married?”

He shook his head. “Freemates, perhaps, we never sought formal ceremonies. If she had wished I would have been willing, but I have seen too many marriage customs on too many worlds to care about any of them. Why?”

“In a tower circle this would not arise; here it must be taken into account,” I said. “Is there any possibility that she could be carrying a child?”

He raised his eyebrow. I knew the question was an inexcusable intrusion, but it was necessary to know. He said at last, “I doubt it. I have traveled on so many worlds and been exposed to so many things … I am older than I look, but I have fathered no children. Probably I cannot. So I fear if Thyra really wants a child she will have to have it fathered elsewhere. Are you volunteering?” he asked, laughing.

I found the question too outrageous even to think about. “I only felt I should warn you that matrix circle work could be dangerous if there was the slightest chance of pregnancy. Not so much for her, but for the unborn child. There have been gruesome tragedies. I felt I should warn you.”

“I should think you’d have done better to warn her,” he said, “but I appreciate your delicacy.” He gave me an odd, unreadable look and went away. Well, I had done no more than my duty in asking, and if the question distressed him, he would have to absorb and accept it, as I absorbed my frustration over Marjorie and accepted the way Thyra’s physical presence disturbed me. My dreams that night were disturbing, Thyra and Marjorie tangling into a single woman, so that again and again I would see one in dreams and suddenly discover it was the other. I should have recognized this as a sign of danger, but I only knew that when it was too late.

The next day was gray and lowering. I wondered if we would have to wait till spring for any really effective work. It might be better, giving us time to settle into our work together, perhaps find others to fit into the circle. Beltran and Kadarin would be impatient. Well, they would just have to master their impatience.

Marjorie looked cold and apprehensive; I felt the same way. A few lonesome snowflakes were drifting down, but I could not make the snow an excuse for putting off the experiment. Even Thyra’s high spirits were subdued.

I unwrapped the sword in which the matrix was hidden. The forge-folk must have done this; I wondered if they had known, even halfway, what they were doing. There were old traditions about matrices like this, installed in weapons. They came out of the Ages of Chaos, when, it is said, everything it’s possible to know about matrices was known, and our world nearly destroyed in consequence.

I said to Beltran, “It’s very dangerous to key into a matrix this size without a very definite end in mind. It must always be controlled or it will take control of us.”

Kadarin said, “You speak as if the matrix was a live thing.”

“I’m not so sure it’s not.” I gestured at the helicopter, standing about eighty feet away at the near edge of the deserted airfield, the snow faintly beginning to edge its tail and rotors. “What I mean is this. We cannot simply key into the matrix, say ‘fly’ and stand here watching that thing take off. We must know precisely howthe mechanism works, in order to know precisely what forces we must exert, and in what directions. I suggest we begin by concentrating on turning the rotor blade mechanism and getting enough speed to lift it. We don’t really need a matrix this size for that, nor five workers. I could do it with this.” I touched the insulated bag which held my own. “But we must have some precise way of learning to direct forces. We will discover, then, how to lift the helicopter and, since we don’t want it to crash, we’ll limit ourselves to turning the rotors until it lifts a few inches, then gradually diminish the speed again until we set it down. Later we can try for direction and control in flight.” I turned to Beltran. “Will this demonstrate to the Terrans that psi power has material uses, so they’ll give us help in developing a way to use this for a stardrive?”

It was Kadarin who answered, “Hell yes! If I know the Terrans!”

Marjorie checked Rafe’s mittened hands. “Warm enough?” He pulled away indignantly, and she admonished, “Don’t be silly! Shivering uses up too much energy; you have to be able to concentrate!” I was pleased at her grasp of this. My own chill was mental, not physical. I placed Beltran at a little distance from the circle. I knew it was a bitter pill to swallow, that the twelve-year-old Rafe could be part of this and he could not, and I was intensely sorry for him, but the first necessity of matrix work was to know and accept for all time your own limitations. If he couldn’t, he had no business within a mile of the circle.

There was really no need for a physical circle, but I drew us close enough that the magnetic energy of our bodies would overlap and reinforce the growing bond.

I knew this was folly, a partly trained Keeper, a partly trained psi monitor … an illegal, unmonitored matrix … and yet I thought of the pioneers in the early days of our world, first taming the matrices. Terran colonists? Kadarin thought so. Before the towers rose, before their use was guarded by ritual and superstition. And it was given to us to retrace their steps!

I separated hilt and blade, taking out the matrix. It was not yet activated, but at its touch the old scar on my palm contracted with a stab of pain. Marjorie moved with quiet sureness into the center of the circle. She stood facing me, laying one hand on the blue stone … a vortex seeking to draw me into its depths, a maelstrom… I shut my eyes, reaching out for contact with Marjorie, steadying myself as I made contact with her cool silken strength. I felt Thyra drop into place, then Kadarin; the sense of an almost-unendurable burden lessened with his strength, as if he shifted a great weight onto his shoulders. Rafe dropped in like some small furry thing nestling against us.

I had the curious sense that power was flowing up from the stone and into the circle. It felt like being hooked up to a powerful battery, vibrating in us all, body and brain. That was wrong, that was very wrong. It was curiously invigorating, but I knew we must not succumb to it even for a moment. With relief I felt Marjorie seize control and with a determined effort direct the stream of force, focusing it through her, outward.

For a moment she stood bathed in flickering, transparent flames, then for an instant she took on the semblance of a woman … golden, chained, kneeling, as the forge-folk depicted their goddess… I knew this was an illusion, but it seemed that Marjorie, or the great flickering fire-form which seemed to loom around and over and through her, reached out, seized the helicopter’s rotors and spun them as a child spins a pinwheel. With my physical ears I heard the humming sound as they began to turn, slowly at first under the controlling force, then winding to a swift spinning snarl, a drone, a shriek that caught the air currents. Slowly, slowly, the great machine lifted, hovering lightly a foot or so above the ground.

Straining to be gone …

Hold it there!I was directing the power outward as Marjorie formed and shaped it; I could feel all the others pressed tightly against me, though physically none of us were touching. As I trembled, feeling the vast outflow of that linked conjoined power, I saw in a series of wild flashes the great form of fire I had seen before, Marjorie and not Marjorie, a raw stream of force, a naked woman, sky-tall with tossing hair, each separate lock a streamer of fire … I felt a curious rage surging up and through me. Take the helicopter, hanging there useless a few inches high, hurl it into the sky, high, high, fling it down like a missile against the towers of Castle Aldaran, burning, smashing, exploding the walls like sand, hurling a rain of fire into the valley, showering fires on Caer Donn, laying the Terran base waste… I struggled with these images of fire and destruction, as a rider struggles with the bit of a hard-mouthed horse. Too strong, too strong.I smelled musk, a wild beast prowled the jungle of my impulses, rage, lust, a constellation of wild emotions … a small skittering animal bolting up a tree in terror … the shriek of the rotor blades, a scream, a deafening roar …

Slowly the noise lessened to a whine, a drone, a faint whir, silence. The copter stood vibrating faintly, motionless. Marjorie, still flickering with faint glimmers of invisible fire, stood calm, smiling absently. I felt her reach out and break the rapport, the others slipping away one by one until we stood alone, locked together. She withdrew her hand from the matrix and I stood cold and alone, struggling against spasms of lust, raging violence spinning in my brain, out of control, my heart racing, the blood pounding in my head, vision blurred …

Beltran touched me lightly on the shoulder; I felt the tumult subside and with a shudder of pain managed to withdraw my consciousness. I covered the matrix quickly and drew my aching hand over my forehead. It came away dripping,

“Zandru’s hells!” I whispered. Never, not in three years at Arilinn, had I even guessed such power. Kadarin, looking at the helicopter thoughtfully, said, “We could have done anything with it.”

“Except maybe controlled it.”

“But the power is there, when we do learn to control it,” Beltran said. “A spaceship. Anything.”

Rafe touched Marjorie’s wrist, very lightly. “For a minute I thought you were on fire. Was that real, Lew?”

I wasn’t sure if this was simply an illusion, the way generations upon generations of the forge-folk had envisioned their goddess, the power which brought metal from the deeps of the earth to their fires and forges. Or was this some objective force from that strange otherworld to which the telepath goes when he steps out of his physical body? I said, “I don’t know, Rafe. How did it seem, Marjorie?”

She said, “I saw the fire. I even felt it, a little, but it didn’t burn me. But I didfeel that if I lost control, even for an instant, it would burn up inside and … and take over, so that I was the fire and could leap down and … and destroy. I’m not saying this very well … ”

Then it was not only me. She too had felt the weapon-rage, the lust for destruction. I was still struggling with their physical aftereffects, the weak trembling of adrenalin expended. If these emotions had actually arisen from within me, I was not fit for this work. Yet, searching within myself, with the discipline of the tower-trained, I found no trace of such emotion within me now.

This disquieted me. If my own hidden emotions—anger I did not acknowledge, repressed desire for one of the women, hidden hostility toward one of the others—had been wrested out of my mind to consume me, then it was a sign I had lost, under stress, my tower-imposed discipline. But those emotions, being mine, I could control. If they were not mine, but had come from elsewhere to fasten upon us, we were all in danger.