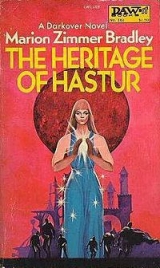

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Regis let them lay him, nearly senseless, on the stone bench.

He let himself slip away into unconsciousness like a little death.

previous | Table of Contents | next

previous | Table of Contents | next

Chapter FOURTEEN

(Lew Alton’s narrative)

For three days a blizzard had raged in the Hellers. On the fourth day I woke to sunshine and the peaks behind Castle Aldaran gleaming under their burden of snow. I dressed and went down into the gardens behind the castle, standing atop the terraces and looking down on the spaceport below where great machines were already moving about, as tiny at this distance as creeping bugs, to shift the heavy layers of snow. No wonder the Terrans didn’t want to move their main port here!

Yet, unlike Thendara, here spaceport and castle seemed part of a single conjoined whole, not warring giants, striding toward battle.

“You’re out early, cousin,” said a light voice behind me. I turned to see Marjorie Scott, warmly wrapped in a hooded cloak with fur framing her face. I made her a formal bow.

“ Damisela.”

She smiled and stretched her hand to me. “I like to be out early when the sun’s shining. It was so dark during the storm!”

As we walked down the terraces she grasped my cold hand and drew it under her cloak. I had to tell myself that this freedom did not imply what it would mean in the lowlands, but was innocent and unaware. It was hard to remember that with my hand lying between her warm breasts. But damn it, the girl was a telepath, she had to know.

As we went along the path, she pointed out the hardy winter flowers, already thrusting their stalks up through the snow, seeking the sun, and the sheltered fruits casting their snow-pods. We came to a marble-railed space where a waterfall tumbled, storm-swollen, away into the valley.

“This stream carries water from the highest peaks down into Caer Donn, for their drinking water. The dam above here, which makes the waterfall, serves to generate power for the lights, here and down in the spaceport, too.”

“Indeed, damisela?We have nothing like this in Thendara.” I found it hard to keep my attention on the stream. Suddenly she turned to face me, swift as a cat, her eyes flashing gold. Her cheeks were flushed and she snatched her hand away from mine. She said, with a stiffness that concealed anger, “Forgive me, DomLewis. I presumed on our kinship,” and turned to go. My hand, in the cold again, felt as chilled and icy as my heart at her sudden wrath.

Without thinking, I reached out and clasped her wrist.

“Lady, how have I offended you? Please don’t go!”

She stood quite still with my hand clasping her wrist She said in a small voice, “Are all you valley men so queer and formal? I am not used to being called damisela, except by servants. Do you … dislike me … Lew?”

Our hands were still clasped. Suddenly she colored and tried to withdraw her wrist from my fingers. I tightened them, saying, “I feared to be burned … too near the fire. I am very ignorant of your mountain ways. How should I address you, cousin?”

“Would a woman of your valley lands be thought too bold if she called you by name, Lew?”

“Marjorie,” I said, caressing the name with my voice. “Marjorie.” Her small fingers felt fragile and live, like some small quivering animal that had taken refuge with me. Never, not even at Arilinn, had I known such warmth, such acceptance. She said my hands were cold and drew them under her cloak again. All she was telling me seemed wonderful. I knew something of electric power generators—in the Kilghard Hills great windmills harnessed the steady winds—but her voice made it all new to me, and I pretended less knowledge so she would go on speaking.

She said, “At one time matrix-powered generators provided lights for the castle. That technique is lost.”

“It is known at Arilinn,” I said, “but we rarely use it; the cost is high in human terms and there is some danger.” Just the same, I thought, in the mountains they must need more energy against the crueler climate. Easy enough to give up a luxury, but here it might make the difference between civilized life and a brutal struggle for existence.

“Have you been taught to use a matrix, Marjorie?”

“Only a little. Kermiac is too old to show us the techniques. Thyra is stronger than I because she and Kadarin can link together a little, but not for long. The techniques of making the links are what we do not know.”

“That is simple enough,” I said, hesitating because I did not like to think of working in linked circles outside the safety of the tower force-fields. “Marjorie, who is Kadarin, where does he come from?”

“I know no more than he told you,” she said. “He has traveled on many worlds. There are times when he speaks as if he were older than my guardian, yet he seems no older than Thyra. Even she knows not much more than I, yet they have been together for a long time. He is a strange man, Lew, but I love him and I want you to love him too.”

I had warmed to Kadarin, sensing the sincerity behind his angry intensity. Here was a man who met life without self-deception, without the lies and compromises I had lived with so long. I had not seen him for days; he had gone away before the blizzard on unexplained business.

I glanced at the strengthening sun. “The morning’s well on. Will anyone be expecting us?”

“I’m usually expected at breakfast, but Thyra likes to sleep late and no one else will care.” She looked shyly up into my face and said, “I’d rather stay with you.”

I said, with a leaping joy, “Who needs breakfast?”

“We could walk into Caer Donn and find something at a food-stall. The food will not be as good as at my guardian’s table … ”

She led the way down a side path, going by a flight of steep steps that were roofed against the spray from the waterfall. There was frost underfoot, but the roofing had kept the stairway free of ice. The roaring of the waterfall made so much noise that we left off trying to talk and let our clasped hands speak for us. At last the steps came out on a lower terrace leading gently downslope to the city. I looked up and said, “I don’t relish the thought of climbing back!”

“Well, we can go around by the horse-path,” she said. “You came up that way with your escort. Or there’s a lift on the far side of the waterfall; the Terrans built it for us, with chains and pulleys, in return for the use of our water power.”

A little way inside the city gates Marjorie led the way to a food-stall. We ate freshly baked bread and drank hot spiced cider, while I pondered what she had said about matrices for generating power. Yes, they had been used in the past, and misused, too, so that now it was illegal to construct them. Most of them had been destroyed, not all. If Kadarin wanted to try reviving one there was, in theory at least, no limit to what he could do with it.

If, that was, he wasn’t afraid of the risks. Fear seemed to have no part in that curious enigmatic personality. But ordinary prudence?

“You’re lost somewhere again Lew. What is it?”

“If Kadarin wants to do these things he must know of a matrix capable of handling that kind of power. What and where?”

“I can only tell you that not on any of the monitor screens in the towers. It was used in the old days by the forge-folk to bring their metals from the ground. Then it was kept at Aldaran for centuries, until one of Kermiac’s wards, trained by him, used it to break the siege of Storn Castle.”

I whistled. The matrix had been outlawed as a weapon centuries ago. The Compact had not been made to keep us away from such simple toys as the guns and blasters of the Terrans, but against the terrifying weapons devised in our Ages of Chaos. I wasn’t happy about trying to key a group of inexperienced telepaths into a really large matrix, either. Some could be harnessed and used safely and easily. Others had darker histories, and the name of Sharra, Goddess of the forge-folk, was linked in old tales with more than one matrix. This one might, or might not, be possible to bring under control.

She said, looking incredulous, “Are you afraid?”

“Damn right,” I said. “I thought most of the talismans of Sharra-worship had been destroyed before the time of Regis Fourth. I knowsome of them were destroyed.”

“This one was hidden by the forge-folk and given back for their worship after the siege of Storn.” Her lip curled. “I have no patience with that kind of superstition.”

“Just the same, a matrix is no toy for the ignorant.” I stretched my hand out, palm upward over the table, to show her the corn-sized white scar, the puckered seam running up my wrist “In my first year of training at Arilinn I lost control for a split second. Three of us had burns like this. I’m not joking when I speak of risks.”

For a moment her face contracted as she touched the puckered scar tissue with a delicate fingertip. Then she lifted her firm little chin and said, “All the same, what one human mind can build, another human mind can master. And a matrix is no use to anyone lying on an altar for ignorant folk to worship.” She pushed aside the cold remnants of the bread and said, “Let me show you the city.”

Our hands came irresistibly together again as we walked, side by side, through the streets. Caer Donn was a beautiful city. Even now, when it lies beneath tons of rubble and I can never go back, it stands in my memory as a city in a dream, a city that for a little while was a dream. A dream we shared.

The houses were laid out along wide, spacious streets and squares, each with plots of fruit trees and its own small glass-roofed greenhouse for vegetables and herbs seldom seen in the hills because of the short growing season and weakened sunlight. There were solar collectors on the roofs to collect and focus the dim winter sun on the indoor gardens.

“Do these work even in winter?”

“Yes, by a Terran trick, prisms to concentrate and reflect more sunlight from the snow.”

I thought of the darkness at Armida during the snow-season. There was so much we could learn from the Terrans!

Marjorie said, “Every time I see what the Terrans have made of Caer Donn I am proud to be Terran. I suppose Thendara is even more advanced.”

I shook my head. “You’d be disappointed. Part of it is all Terran, part of it all Darkovan. Caer Donn … Caer Donn is like you, Marjorie, the best of each world, blended into a single harmonious whole … ”

This was what our world could be. Should be. This was Beltran’s dream. And I felt, with my hands locked tight in Mariorie’s, in a closeness deeper than a kiss, that I would risk anything to bring that dream alive and spread it over the face of Darkover. I said something about how I felt as we climbed together upward again. We had elected to take the longer way, reluctant to end this magical interlude. We must have known even then that nothing to match this morning would ever come again, when we shared a dream and saw it all bright and new-edged and too beautiful to be real.

“I feel as if I were drugged with kirian!”

She laughed, a silvery peal. “But the kiresethno longer blooms in these hills, Lew. It’s all real. Or it can be.”

I began as I had promised later that day. Kadarin had not returned, but the rest of us gathered in the small sitting room.

I felt nervous, somehow reluctant. It was always nerve-racking to work with a strange group of telepaths. Even at Arilinn, when the circle was changed every year, there was the same anxious tension. I felt naked, raw-edged. How much did they know. What skills, potentials, lay hidden in these strangers? Two women, a man and a boy. Not a large circle. But large enough to make me quiver inside.

Each of them had a matrix. That didn’t really surprise me since tradition has it that the matrix jewels were first found in these mountains. None of them had his or her matrix what I would call properly safeguarded. That didn’t surprise me either. At Arilinn we’re very strict in the old traditional ways. Like most trained technicians, I kept mine on a leather thong around my neck, silk-wrapped and inside a small leather bag, lest some accidental stimulus cause it to resonate.

Beltran’s was wrapped in a scrap of soft leather and thrust into a pocket. Marjorie’s was wrapped in a scrap of silk and thrust into her gown between her breasts, where my hand had lain! Rafe’s was small and still dim; he had it in a small cloth bag on a woven cord around his neck. Thyra kept hers in a copper locket, which I considered criminally dangerous. Maybe my first act should be to teach them proper shielding.

I looked at the blue stones lying in their hands. Marjorie’s was the brightest, gleaming with a fiery inner luminescence, giving the lie to her modest statement that Thyra was the stronger telepath. Thyra’s was bright enough, though. My nerves were jangling. A “wild telepath,” one who has taught himself by trial and error, extremely difficult to work with. In a tower the contact would first be made by a Keeper, not the old carefully-shielded leronisof my father’s day, but a woman highly trained, her strength safeguarded and disciplined. Here we had none. It was up to me.

It was harder than taking my clothes off before such an assembly, yet somehow I had to manage it. I sighed and looked from one to the other.

“I take it you all know there’s nothing magical about a matrix,” I said. “It’s simply a crystal which can resonate with, and amplify, the energy-currents of your brain.”

“Yes, I know that,” said Thyra with amused contempt “I didn’t expect anyone trained by Comyn to know it, though.”

I tried to discipline my spontaneous flare of anger. Was she going to make this as hard for me as she could?

“It was the first thing they taught me at Arilinn, kinswoman, I am glad you know it already.” I concentrated on Rafe. He was the youngest and would have least to unlearn.

“How old are you, little brother?”

“Thirteen this winter, kinsman,” he said, and I frowned slightly. I had no experience with children—fifteen is the lowest age limit for the Towers—but I would try. There was light in his matrix, which meant that he had keyed it after a fashion.

“Can you control it?” We had none of the regular test materials; I would have to improvise. I made brief contact. The fireplace. Make the fire flame up twice and die down.

The stone reflected blue glimmer on his childish features as he bent, his forehead wrinkling up with the effort of concentration. The light grew; the fire flamed high, sank, flared again, sank down, down …

“Careful,” I said, “don’t put it out. It’s cold in here.” At least he could receive my thoughts; though the test was elementary, it qualified him as part of the circle. He looked up, delighted with himself, and smiled.

Marjorie’s eyes met mine. I looked quickly away. Damn it, it’s never easy to make contact with a woman you’re attracted to. I’d learned at Arilinn to take it for granted, for psi work used up all the physical and nervous energy available. But Marjorie hadn’t learned that, and I felt shy. The thought of trying to explain it to her made me squirm. In the safe quiet of Arilinn, chaperoned by nine or ten centuries of tradition, it was easy to keep a cool and clinical detachment. Here we must devise other ways of protecting ourselves.

Thyra’s eyes were cool and amused. Well, sheknew. If she and Kadarin had been working together, no doubt she’d found it out already. I didn’t like her and I sensed she didn’t like me either, but thus far, at least, we could touch one another with easy detachment; her physical presence did not embarrass me. Where, working alone, had she picked up that cool, knife-like precision? Was I glad or sorry that Marjorie showed no sign of it?

“Beltran,” I said, “what can you do?”

“Children’s tricks,” he said, “little talent, less skill. Rafe’s trick with the fire.” He repeated it, more slowly, with somewhat better control. He reached an unlighted taper from a side table and bent over it with intense concentration. A narrow flame leaped from the fireplace to the tip of the taper, where it burst into flame.

A child’s trick, of course, one of the simplest tests we used at Arilinn. “Can you call the fire without the matrix?” I asked.

“I don’t try,” he said. “In this area it’s too great a danger to set something on fire. I’d rather learn to put fires out. Do your tower telepaths do that, perhaps, in forest-fire country?”

“No, though we do call clouds and make rain sometimes. Fire is too dangerous an element, except for baby tricks like these. Can you call the overlight?”

He shook his head, not understanding. I held out my hand and focused the matrix. A small green flame flickered, grew in the palm of my hand. Marjorie gasped. Thyra held out her own hand; cold white light grew, pale around her fingers, lighting up the room, flaring up like jagged lightning. “Very good,” I said, “but you must control it. The strongest or brightest light is not always the best. Marjorie?”

She bent over the blue shimmer of her matrix. Before her face, floating in the air, a small blue-white ball of fire appeared, grew gradually larger, then floated to each of us in turn. Rafe could make only flickers of light; when he tried to shape them or move them, they flared up and vanished. Beltran could make no light at all. I hadn’t expected it. Fire, the easiest of the elements to call forth, was still the hardest to control.

“Try this.” The room was very damp; I condensed the moist air into a small splashing fountain of water-drops, each sizzling a moment in the fire as it vanished. Both of the women proved able to do this easily; Rafe mastered it with little trouble. He needed practice, but had excellent potential.

Beltran grimaced, “I told you I had small talent and less skill.”

“Well, some things I can teach you without talent, kinsman,” I said. “Not all mechanics are natural telepaths. Do you read thoughts at all?”

“Only a little. Mostly I sense emotions,” he said.

Not good. If he could not link minds with us, he would be no use in the matrix circle. There were other things he could do, but we were too few for a circle, except for the very smallest matrices.

I reached out to touch his mind. Sometimes a telepath who has never learned the touching technique can be shown, when all else fails. I met slammed, locked resistance. Like many who grow up with minimal laran, untrained, he had built defenses against tbe use of his gift. He was cooperative, letting me try again and again to force down the barrier, and we were both white and sweating with pain by the time I finally gave up. I had used a force on him far harder than I had used on Regis, to no avail.

“No use,” I said at last. “Much more of this will kill both of us. I’m sorry, Beltran. I’ll teach you what I can outside the circle, but without a catalyst telepath this is as far as you can go.” He looked miserably downcast, but he took it better than I had hoped.

“So the women and children can succeed where I fail. Well, if you’ve done the best you can, what can I say?”

It was, on the contrary, easy to make contact with Rafe. He had built no serious defense against contact, and I gathered, from the ease and confidence with which he dropped into rapport with me, that he must have had a singularly happy and trusting childhood, with no haunting fears. Thyra sensed what we had done; I felt her reach out, and made the telepathic overture which is the equivalent of an extended hand across a gulf. She met it quickly, dropping into contact without fumbling, and …

A savage animal, dark, sinuous, prowling an unexplored jungle. A smell of musk … claws at my throat …

Was this her idea of a joke? I broke the budding rapport, saying tersely, “This is no game, Thyra. I hope you never find that out the hard way.”

She looked bewildered. Unconscious, then. It was just the inner image she projected. Somehow I’d have to learn to live with it. I had no idea how she perceived me. That’s one thing you can never know. You try, of course, at first. One girl in my Arilinn circle had simply said I felt “steady.” Another tried, confusedly, to explain how I “felt” to her mind and wound up saying I felt like the smell of saddle-leather. You’re trying, after all, to put into words an experience that has nothing to do with verbal ideas.

I reached out for Marjorie and sensed her in the fragmentary circle … a falling swirl of golden snowflakes, silk rustling, like her hand on my cheek. I didn’t need to look at her. I broke the tentative four-way contact and said, “Basically, that’s it. Once we learn to match resonances.”

“If it’s so simple, why could we never do it before?” Thyra demanded.

I tried to explain that the art of making a link with more than one other mind, more than one other matrix, is the most difficult of the basic skills taught at Arilinn. I felt her fumbling to reach out, to make contact, and I dropped my barriers and allowed her to touch me. Again the dark beast, the sense of claws …Rafe gasped and cried out in pain and I reached out to knock Thyra loose. “Not until you know how,” I said. “I’ll try to teach you, but you have to learn the precise knack of matching resonance beforeyou reach out. Promise me not to try it on your own, Thyra, and I’ll promise to teach you. Agreed?”

She promised, badly shaken by the failure. I felt depressed. Four of us, then, and Rafe only a child. Beltran unable to make rapport at all, and Kadarin an unknown quantity. Not enough for Beltran’s plans. Not nearly enough.

We needed a catalyst telepath. Otherwise, that was as far as I could go.

Rafe’s attempts to lower the fire and our experiments with water-drops had made the hearth smolder; Marjorie began to cough. Any of us could have brought it back to brightness, but I welcomed the chance to get out of the room. I said, “Let’s go into the garden.”

The afternoon sunshine was brilliant, melting the snow. The plants which had just this morning been thrusting up spikes through snow were already budding. I asked, “Will Kermiac be angry if we destroy a few of his flowers?”

“Flowers? No, take what you need, but what will you do with them?”

“Flowers are ideal test and practice material,” I said. “It would be dangerous to experiment with most living tissue; with flowers you can learn a very delicate control, and they live such a short time that you are not interfering with the balance of nature very much. For instance.” Cupping matrix in hand, I focused my attention on a bud full-formed but not yet opened, exerting the faintest of mental pressures. Slowly, while I held my breath, the bud uncurled, thrusting forth slender stamens. The petals unfolded, one by one, until it stood full-blown before us. Marjorie drew a soft breath of excitement and surprise.

“But you didn’t destroy it!”

“In a way I did; the bud isn’t fully mature and may never mature enough to be pollinated. I didn’t try; maturing a plant like that takes deep intercellular control. I simply manipulated the petals.” I made contact with Marjorie. Try it with me. Try first to see deep into the cell structure of the flower, to see exactly how each layer of petals is folded …

The first time she lost control and the petals crushed into an amorphous, colorless mass. The second time she did it almost as perfectly as I had done. Thyra, too, quickly mastered the trick, and Rafe, after a few tries. Beltran had to struggle to achieve the delicate control it demanded, but he did it. Perhaps he would make a psi monitor. Nontelepaths sometimes made good ones.

I saw Thyra by the waterfall, gazing into her matrix. I did not speak to her, curious to see what she could do unaided. It was growing late—we had spent considerable time with the flowers—and dusk was falling, lights appearing here and there in the city below us. Thyra stood so still she hardly appeared to breathe. Suddenly the raging, foaming torrent next to her appeared to freeze motionless, arrested in midair, only one or two of the furthest droplets floating downward. The rest hung completely stopped, poised, frozen as if time itself and motion had stopped. Then, deliberately, the water began to flow uphill.

Beneath us, one after another, the lights of Caer Donn blinked and went out.

Rafe gasped aloud; in the eerie stillness the small sound brought me back to reality. I said sharply, “Thyra!” she started, her concentration broken, and the whole raging torrent plunged downward with a crash.

Thyra turned angry eyes on me. I took her by the shoulder and drew her back from the edge, to where we could hear ourselves speak above the torrent

“Who gave you leave to meddle—!”

I deliberately smothered my flare of anger. I had assumed responsibility for all of them now, and Thyra’s ability to make me angry was something I must learn to control. I said, “I am sorry, Thyra, had you never been told that this is dangerous?”

“Danger, always danger! Are you such a coward, Lew?” I shook my head. “I’m past the point where I have to prove my courage, child.” Thyra was older than I, but I spoke as to a rash, foolhardy little girl. “It was an astonishing display, but there are wiser ways to prove your skill.” I gestured. “Look, you have put their lights out; it will take repair crews some time to restore their power relays. That was thoughtless and silly. Second, it is unwise to disturb the forces of nature without great need, and for some good reason. Remember, rain in one place, even to drown a forest fire, may mean drought elsewhere, and balance disturbed. Until you can judge on planet-wide terms, Thyra, don’t presume to meddle with a natural force, and never, never,for your pride! Remember, I asked Beltran’s leave even to destroy a few flowers!”

She lowered her long lashes. Her cheeks were flaming, like a small girl lectured for some naughtiness. I regretted the need to lay down the law so harshly, but the incident had disturbed me deeply, rousing all my own misgivings. Wild telepaths were dangerous! How far could I trust any of them?

Marjorie came up to us; I could tell that she shared Thyra’s humiliation, but she made no protest. I turned and slipped my arm around her waist, which would have proclaimed us acknowledged lovers in the valley. Thyra sent me a sardonic smile of amusement beneath her meekly dropped lashes, but all she said was, “We are all at your orders, DomLewis.”

“I’ve no wish to give orders, cousin,” I said, “but your guardian would have small cause to love me if I disregarded the simplest rules of safety in your training!”

“Leave him alone, Thyra,” Marjorie flared. “He knows what he’s doing! Lew, show her your hand!” She seized the palm, turned it over, showing the white ridged scars. “He has learned to follow rules, and learned it with pain! Do you want to learn like that?”

Thyra flinched visibly, averting her eyes from the scar as if it sickened her. I would not have thought her squeamish. She said, visibly shaken, “I had never thought … I did not know. I’ll do what you say, Lew. Forgive me.”

“Nothing to forgive, kinswoman,” I said, laying my free hand on her wrist. “Learn caution to match your skill and you will be a strong leronissome day.” She smiled at the word which, taken literally, meant sorceress.

“Matrix technician, if you like. Some day, perhaps, there will be new words for new skills. In the towers we are too busy mastering skills to worry about words for them, Thyra. Call it what you like.”

Thin fog was beginning to move down from the peaks behind the castle. Marjorie shivered in her light dress and Thyra said, “We’d better go in, it will be dark soon.” With one bleak look at the darkened city below, she walked quickly toward the castle. Marjorie and I walked with our arms laced, Rafe tagging close to us.

“Why do we need the kind of control we practiced with the flowers, Lew?”

“Well, if someone in the circle gets so involved in what he’s doing that he forgets to breathe, the monitor outside has to start him breathing again without hurting him. A well-trained empath can stop bleeding even from an artery, or heal wounds.” I touched the scar. “This would have been worse, except that the Keeper of the circle worked with it, to heal the worst damage.” Janna Lindir had been Keeper at Arilinn for two of my three years. At seventeen, I had been in love with her. I had never touched her, never so much as kissed her fingertips. Of course.

I looked at Marjorie. No. No, I have never loved before, never … The other women I have known have been nothing …

She looked at me and whispered, half laughing, “Have you loved so many?”

“Never like this. I swear it—”

Unexpectedly she threw her arms around me, pressed herself close. “I love you,” she whispered quickly, pulled away and ran ahead of me along the path into the hall.

Thyra smiled knowingly at me as we came in, but I didn’t care. You had to learn to take that kind of thing for granted. She swung around toward the window, looking into the gathering darkness and mist. We were still close enough that I followed her thoughts. Kadarin, where was he, how did he fare on his mission?I began to draw them together again, Marjorie’s delicate touch, Rafe alert and quick like some small frisking animal, Thyra with the strange sense of a dark beast prowling.

Kadarin.The interlinked circle formed itself and I discovered to my surprise, and momentary dismay, that Thyra was at the center, weaving us about her mind. But she seemed to work with a sure, deft touch, so I let her keep that place. Suddenly I sawKadarin, and heard his voice speaking in the middle of a phrase:

“ … refuse me then, Lady Storn?”

We could even see the room where he was standing, a high-arched old hall with the blue glass windows of almost unbelievable antiquity. Directly before his eves was a tall old woman, proudly erect, with gray eyes and dazzling white hair. She sounded deeply troubled.

“Refuse you, dom? I have no authority to give or refuse. The Sharra matrix was given into the keeping of the forge-folk after the siege of Storn. It had been taken from them without authority, generations ago, and now it is safe in their keeping, not mine. It is theirs to give.”