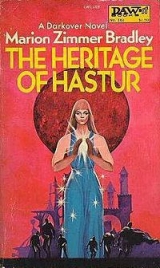

Текст книги "Heritage Of Hastur"

Автор книги: Marion Zimmer Bradley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 28 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Regis was remembering their long talk in the tavern and Dyan’s flippancy about his lack of an heir. He was not flippant now. His face had paled to its former impassivity. He said, “My nearest kinsman sits among the Terrans. I must first ask if he is prepared to renounce that allegiance. Daniel Lawton, you are the only son of the eldest of my father’s nedestrodaughters, Rayna di Asturien, who married the Terran David Daniel Lawton. Are you prepared to renounce your Empire citizenship and swear allegiance to Comyn?”

Dan Lawton blinked in amazement. He did not answer immediately, but Regis sensed—and knew, when he spoke a minute later—that the hesitation had been only a form of courtesy. “No, Lord Ardais,” he said in casta, “I have given my loyalty and will not now renounce it. Nor would you wish it so; the man who is false to his first allegiance will be false to his second.”

Dyan bowed and said, with a note of respect, “I honor your choice, kinsman. I ask the Council to bear witness that my nearest kinsman has renounced all claim upon me and mine.”

There was a brief murmur of assent.

“Then I turn to my privileged choice,” Dyan said. His voice was hard and unyielding. “Second among my near kinsmen was another nedestrodaughter of my father; her son has been confirmed by the Keeper at Neskaya to be one who holds the Ardais gift. His mother was Melora Castamir and his father Felix-Rafael Syrtis, who is of Alton blood. Danilo-Felix Syrtis,” Dyan said, “upon the grounds of Comyn blood and Ardais gift, I call upon you to swear allegiance to Comyn as heir to the Ardais Domain; and I am prepared to defend my choice against any man who cares to challenge me.” His eyes moved defiantly against them all.

It was like a thunderclap. So these were Dyan’s honorable amends! Regis could not tell whether the thought was his own or Danilo’s, as Danilo, dazed, moved toward Dyan.

Regis remembered how he’d thought Dani should have a seat on Comyn Council! But like this? Did Kennard engineer this?

Dyan said formally, “Do you accept the claim, Danilo?”

Danilo was shaking, though he tried to control his voice. “It is … my duty to accept it, Lord Ardais.”

“Then kneel, Danilo, and answer me. Will you swear allegiance to Comyn and this Council, and pledge your life to serve it? Will you swear to defend the honor of Comyn in all just causes, and to amend all evil ones?” Dyan’s speaking voice was rich, strong and musical, but now he hesitated, his voice breaking. “Will you grant to me … a son’s duty … until such time as a son of my body may replace you?”

Regis thought, suddenly wrung by Dyan’s torment, who has taken revenge on whom? He could see that Danilo was crying silently as Dyan’s wavering voice went out: “Will you swear to be a … a loyal son to me, until such time as I yield my Domain through age, unfitness or infirmity, and then serve as my regent under this Council?”

Dani was silent for a moment and Regis, close in rapport with him, knew he was trying to steady his voice. At last, shaking, his voice almost inaudible, he whispered, “I will swear it.”

Dyan bent and raised him to his feet. He said steadily, “Bear witness that this is my nedestroheir; that none shall take precedence from him; and that this claim”—his voice broke again—“may never be renounced by me nor in my name by any of my descendants.”

Briefly, and with extreme formality, he embraced him. He said quietly, but Regis heard, “You may return for the time to your sworn service, my son. Only in my absence or illness need you take a place among the Ardais. You must attend this Council and all its affairs must be known to you, however, since you may need to assume my place unexpectedly.”

As if he were walking in his sleep, Danilo returned to his place beside Regis. Bearing himself with steady pride, he slid into the seat beside him. Then he broke and laid his head on the table before them, his head in his arms, crying. Regis reached his hand to Danilo, clasped his arm above the elbow, but he did not speak or reach out with his thoughts. Some things were too painful even for a sworn brother’s touch. He did think with a curious pain, that Dyan had made them equals, Dani was heir to a Domain; he need be no man’s paxman nor vassal, nor seek Regis’ protection now. And no one could ever again speak of disgrace or dishonor.

He knew he should rejoice for Danilo, he did rejoice for him. But his friend was no longer dependent on him and he felt unsure and strange.

“Regis-Rafael Hastur, Regent-heir of Hastur,” Danvan Hastur said. In the shock of Dyan’s act, Regis had wholly forgotten that he, too, was to speak before the Council. Danilo lifted his head, nudged him gently and whispered, in a voice that could be heard two feet away, “That’s you, blockhead!”

For a moment Regis thought he would break into hysterical giggles at this reminder. Lord of Light, he could not! Not at a formal ceremony! He bit his lip hard and would not meet Danilo’s eyes, but as he rose and went forward he was no longer worried about what their relationship might become after this. He had been a fool to worry at all.

“Regis-Rafael,” his grandfather said, “vows were made in your name when you were six months old, as heir-designate of Hastur. Now that you have reached the age of manhood, it is for you to affirm them or reject them, in full knowledge of what they entail. You have been affirmed by the Keeper of Neskaya Tower as possessing full laran, and you are therefore capable of receiving the Hastur gift at the proper time, Have you an heir?” He hesitated, then said kindly, “The law provides that until your twenty-fourth year you need not repeat formal vows of allegiance nor name an heir-designate. And you cannot be legally compelled to marry until that time.”

He said quietly, “I have a designated heir.” He beckoned to Gabriel Lanart-Hastur, who stepped into the hallway, taking from a nurse’s arms the small plump body of Mikhail. Gabriel carried him to Regis, and Regis set the child down in the center of the rainbow lights. He said, “Bear witness that this is my nedestroheir, a child of Hastur blood, known to me. He is the son of my sister Javanne Hastur, who is the daughter of my mother and of my father, and of her lawful consort di catenas, Gabriel Lanart-Hastur. I have given him the name of Danilo Lanart Hastur. Because of his tender years, it is not yet lawful to ask him for any formal oath. I will ask him only, as it is my duty to do: Danilo Lanart Hastur, will you be a good son to me?”

The child had been carefully coached for the ceremony but for a moment he did not answer and Regis wondered if he had forgotten. Then he smiled and said, “Yes, I promise.”

Regis lifted him and kissed his chubby cheek; the little boy flung his arms around Regis’ neck and kissed him heartily. Regis could not help smiling as he handed him back to his father, saying quietly, “Gabriel, will you pledge to foster and rear him as my son and not your own?”

Gabriel’s face was solemn. He said, “I swear it on my life and my honor, kinsman.”

“Then take him, and rear him as befits the heir to Hastur, and the Gods deal with you as you with my son.”

He watched Gabriel carry the child away, thinking soberly that his own life would have been happier if his grandfather had given him entirely up to Kennard to foster, or to some other kinsman with sons and daughters, Regis vowed not to make that mistake with Mikhail.

And yet he knew his grandfather’s distant affection, and the harsh discipline at Nevarsin, too, had contributed to what he had become. Kennard was fond of saying, “The world will go as it will, not as you or I would have it.” And for all Regis’ struggles to escape from the road laid out before birth for the Hastur heir, it had brought him here, at the appointed time. He turned to the Regent, thinking with pain that he did not have to do this. He was still free. He had promised three years. But after this he would never again be wholly free.

He met Danilo’s eyes, felt that somehow their steady, affectionate gaze gave him strength.

He said, “I am ready to repeat my oath, Lord Hastur.” Hastur’s old face was drawn, tense with emotion. Regis felt his thoughts, unbarriered, but Hastur said, with the control of fifty years in public life, “You have arrived at years of manhood; if it is your free choice, none can deny you that right.”

“It is my free choice,” Regis said. Not his wish. But his will, his choice. His fate. The old Regent left his place, then, came to the center of the prismed lights. “Kneel, then Regis-Rafael.” Regis knelt. He knew he was shaking. “Regis-Rafael Hastur, will you swear allegiance to Comyn and this Council, pledge your life to serve it? Will you … ” He went on. Regis heard the words through a wavering mist of pain: never to be free. Never to look at the great ships bound outward to the stars and know that one day he would follow them to those distant worlds. Never to dream again …

“ … pledge yourself to be a loyal son to me until I yield my place through age, unfitness or infirmity, and then to serve as Regent-heir subject to the will of this Council?”

Regis thought, for a moment, that he would break into weeping as Danilo had done. He waited, summoning all his control, until he could lift his head and say, in a clear, ringing voice, “I swear it on my life and honor.”

The old man bent, raised Regis, clasped him in his arms and kissed him on either cheek. His hands were trembling with emotion, his eyes filled with tears that ran, unheeded, down his face. And Regis knew that for the first time in his life, his grandfather saw him, him alone. No ghost, no shadow of his dead son, stood between them. Not Rafael. Regis, himself.

He felt suddenly, immensely lonely. He wished this council were over. He walked back to his seat. Danilo respected his silence and did not speak or look at him. But he knew Danilo was there and it warmed, a little, the cold shaking loneliness inside him.

Hastur had mastered his emotion. He said, “Kennard, Lord Alton.”

Kennard still limped heavily, and he looked weary and worn, but Regis was glad to see him on his feet again. He said, “My lords, I bring you news from Arilinn. It has been determined there that the Sharra matrix can neither be monitored nor destroyed at present. Until such time as a means of completely inactivating it can be devised, it has been decided to send it offworld, where it cannot fall into the wrong hands and cannot raise again its own specific dangers.”

Dyan said, “Isn’t that dangerous, too, Kennard? If the power of Sharra is raised elsewhere—”

“After long discussion, we have determined that this is the safest course. It is our opinion that there are no telepaths anywhere in the Empire who are capable of using it. And at interstellar distances, it cannot draw upon the activated spots near Aldaran, which is always a risk while it remains on Darkover. Even the forge-folk could not hold it inactive now. Offworld, it will probably be dormant until a means of destroying it can be devised.”

“It’s a risk,” Dyan said.

“ Everythingis a risk, while anything of such power remains active in the universe anywhere,” Kennard said. “We can only do the best we can with the tools and techniques we have.”

Hastur said, “You are going to take it offworld yourself, then? What of your son? He was at least partly responsible for its use—”

“No,” said Danilo suddenly, and Regis realized that Danilo now had as much right as anyone there to speak in Council, “he refused to have any part in its misuse, and endured torture to try to prevent it!”

“And,” Kennard said, “he risked his life and came near to losing it, to bring it to Arilinn and break the circle of destruction. If he and his wife had not risked their lives—and if the girl had not sacrificed her own—Sharra would still be raging in the hills and none of us would sit here peacefully deciding who is to sit in Council after us!” Suddenly the Alton rage flared out, lashing them all. “Do you know the price he paid for you Comyn, who had despised him and treated him with contempt, and not one of you, not a damned one of you, have so much as asked whether he will live or die?”

Regis felt flayed raw by Kennard’s pain. He was sent to Neskaya, but he knew he should somehow have contrived to send a message.

Kennard said harshly, “I came to ask leave to take him to Terra, where he may regain his health, and perhaps save his reason.”

“Kennard, by the laws of the Comyn, you and your heir may not both go offworld at once.”

Kennard looked at Hastur in open contempt and said, “The laws of the Comyn be damned! What have I gained for keeping them, what have my ten years in Council gained me? Try to stop me, damn you. I have another son, but I’m not going through all that rigamarole again. You accepted Lew, and look what it’s done for him!” Without the slightest vestige of formal leave-taking, he turned his back on them all and strode out of the Crystal Chamber.

Regis got hurriedly to his feet and went after him; he knew Danilo followed noiselessly at his heels. He caught up with Kennard in the corridor. Kennard whirled, still hostile, and said, “What the hell—”

“Uncle, what of Lew? How is he? I have been in Neskaya, I could not—don’t damn me with them, Uncle.”

“How would you expect him to be?” Kennard demanded, still truculent, then his face softened. “Not very well, Regis. You haven’t seen him since we brought him from Arilinn?”

“I didn’t know he was well enough to travel.”

“He isn’t. We brought him in a Terran plane from Arilinn. Maybe they can save his hand. It’s still not certain.”

“You’re going to Terra?”

“Yes, we leave within the hour. I haven’t time to argue with your damned Council and I won’t have Lew badgered.” Angry as he sounded, Regis knew it was despair, not hostility, behind Kennard’s harsh voice. He tried to barricade himself against the despairing grief. At Nescaya he had been taught the basic techniques of closing out the worst of it; he no longer felt wholly naked, wholly stripped. He could face Dyan now, and even with Danilo they need not lower their barriers unless they both wished it.

“Uncle, Lew and I have been friends since I was only a little boy. I—I would like to see him to say farewell.”

Kennard regarded him with hostility for some seconds, at last saying, “Come along, then. But don’t blame me if he won’t speak to you.” His voice was not steady either.

Regis could not help recalling the last time he had stood here in the great hall of the Alton rooms, before Kennard and his grandfather. And the time before that. Lew was sitting on a bench before the fireplace. Exactly where he was sitting that night when Regis appealed to him to waken his laran.

Kennard asked gently, “Lew, will you speak to Regis? He came to bid you farewell.”

Lew’s barriers were down and Regis felt the naked surge of pain, rejection: I don’t want anyone, I don’t want anyone to see me now.It was like a blow, sending Regis reeling. But he braced himself against it, saying very softly, “ Bredu—”

Lew turned and Regis shrank, almost with horror, from the first sight of that hideously altered face. Lew had aged twenty years in the few short weeks since they had parted. His face was a terrible network of healed and half-healed scars. Pain had furrowed deep lines there, and the expression in his eyes was of someone who has looked on horrors past endurance. One hand was bundled in clumsy bandages and braced in a sling. He tried to smile but it was only a grimace.

“Sorry. I keep forgetting, I’m a sight to frighten children into fits.”

Regis said, “But I’m not a child, Lew.” He managed to block out the other man’s pain and misery and said as calmly as he could manage, “I suppose the worst of the scars will heal.”

Lew shrugged, as if that was a matter of deadly indifference. Regis still looked uneasily at him; now that they were together he was uncertain why he had come. Lew had gone dead to all human contact and wanted it that way. Any closer contact between them, any attempt to reach him with laran, to revive their old closeness, would simply breach that merciful numbness and revive Lew’s active suffering. The quicker he said goodbye and went away again, the better it would be.

He made a formal bow, resolving to keep it that way, and said, “A good journey, then, cousin, and a safe return.” He started to move backward. He bumped into Danilo in his retreat, and Danilo’s hand closed over his wrist, the touch opening a blaze of rapport between them. As clearly as if Danilo had spoken aloud, Regis felt the intense surge of his distress:

No, Regis! Don’t shut it all out, don’t withdraw from him! Can’t you see he’s dying inside there, locked away from everyone he loves? He’s got to know that you know what he’s suffering, that you don’t shrink from him! I can’t reach him, but you can because you’ve loved him, and you must, before he slams down the last barrier and locks everyone out forever. It’s his reason at stake, maybe his life!

Regis recoiled. Then, torn, agonized, he realized that this, too, was the burden of his heritage: to accept that nothing, nothing in the human mind, was too fearful to face, that what one person could suffer, another could share. He had known that when he was only a child, before his laranwas fully awake. He hadn’t been afraid then, or ashamed, because he wasn’t thinking of himself then at all, but only of Lew, because he was afraid and in pain.

He let go of Danilo’s hand and took a step toward Lew. One day—it flashed through his mind at random and, it seemed, irrelevantly—as the telepathic men of his caste had always done, he would go down, with the woman bearing his child, into the depths of agony and the edge of his death, and he would be able, for love, to face it. And for love he could face this, too. He went to Lew. Lew had lowered his head again. Regis said, “ Bredu,” and stood on tiptoe, embracing his kinsman, and deliberately laying himself open to all of Lew’s torment, taking the full shock of rapport between them.

Grief. Bereavement. Guilt. The shock of loss, of mutilation. The memory of torture and terror. And above all, guilt, terrible guilt even at being alive, alive when those he had loved were dead …

For a moment Lew fought to shut away Regis’ awareness, to block him out, too. Then he drew a long, shaking breath, raised his uninjured arm and pressed Regis close.

… you remember now. I know, I know, you love me, and you have never betrayed that love…

“Goodbye, bredu,” he said, in a sharp aching voice which somehow hurt Regis far less than the calm controlled formality, and kissed Regis on the cheek. “If the Gods will, we shall meet again. And if not, may they be with you always.” He let Regis go, and Regis knew he could not heal him, nor help him much, not now. No one could. But perhaps, Regis thought, perhaps, he had kept a crack open, just enough to let Lew remember that beside grief and guilt and loss and pain, there was love in the world, too.

And then, out of his own forfeited dreams and hope, out of the renunciation he had made, still raw in his mind, he offered the only comfort he could, laying it like a gift before his friend:

“But you have another world, Lew. And you are free to see the stars.”

previous | Table of Contents