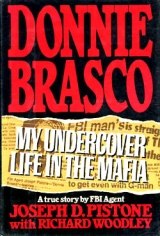

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

At that feast in 1977, a bunch of us were sitting in a coffee shop on Mulberry Street at one A.M., Lefty and a couple other guys and a couple local girls. One girl was sitting next to me. Suddenly she’s rubbing my leg under the table. She says, “Where you going when you leave here?”

“Over to see my girl in Jersey.”

“Why don’t you stay in the city tonight?”

This girl is the daughter of a wiseguy, and her father is in the coffee shop. I have to be careful not to insult her because she might tell her old man that I’m grabbing her leg or something, and then I’m history—you don’t do that to a wiseguy’s daughter.

“I’m pretty true to my girl,” I say. “I promised I was coming over. I’d rather not lie to her.”

“How come you never bring her around?”

“No reason to.”

“Well, if you ever get the urge to go out, give me a call.”

“Okay, I will. Sometime when I don’t have to lie.” I squirmed out of that one.

One of Mirra’s operations was coin machines. He dealt in slots, peanut vending machines, game machines, pinball machines. He had them installed all over the city in stores, luncheonettes, clubs, after-hours places. Slot machines, since they were illegal, would be installed in back rooms. He would take me along on his route when he collected the money from the machines and when he got new business.

To collect, he just went in, opened the machines with a key, counted the money, and gave the store owner his cut—$25 or whatever it was. He would put the rest in a paper bag and out we would go. His route produced maybe $2,000 a week.

To get a new customer Mirra would walk into a place, tell the owner he was Tony and that the store needed one of his machines. Often the owner would recognize him or the name and say something like, “Oh, yeah, Tony, I was just thinking of calling you to get a machine in here.” If the guy didn’t think he was interested at first, Mirra would say, “In the next twenty-four hours, check around, ask about Tony down on Mulberry Street. Then I’ll come back and see if you’ve changed your mind.”

Invariably the owner had changed his mind when we came back.

He was trying to get his slot machines into Atlantic City. He said the family had five hundred slots in a warehouse, and he was just waiting for his lawyers to come up with a way to get access for them along the boardwalk.

Mirra says to me, “Drive me uptown.”

“What’s the problem?”

“I got to meet a guy that owes me money.”

He was collecting on one of his shylock loans.

We drive to a restaurant on First Avenue. We go in and stand at the bar. Pretty soon this guy walks in, tough-looking, about thirty. He comes over to Mirra and starts to open his mouth.

“Don‘t,” Mirra says, holding up his hand. “Don’t mention anybody’s name or I’m gonna smack you right here.”

Mob protocol is that if the guy says he talked to another wiseguy about the situation, mentions another wiseguy’s name, then Mirra would first have to talk to the other wiseguy. So he wasn’t giving this guy a chance to mention anybody’s name.

Mirra says, “Just answer the question I ask you. Where’s my fucking money?”

“Geez, Tony, you’re gonna get it, I’m just having a hard time, but I’ll have it for you, you know—”

“I heard this now a couple weeks,” Mirra says. “But it don’t happen. Let’s take a walk.”

Now I’m worried. If Mirra takes him out, this guy could end up in the alley next door. Mirra would beat him up or stab him. It was one of those situations where, as an agent, I had to intercede. But at the same time I had to maintain my role.

I say, “Hey, Tony, why don’t you let me talk to the guy, save you the aggravation. I’ll take him out for a walk.”

He nods to me and shoves the guy toward the door.

I take him outside. I figure at least I can buy some time, let Tony cool down. I say, “Look, I just saved you. I don’t want to see you get killed, but next time it ain’t gonna be that easy. When we go back in there, you say, ‘Tony, can I meet you tomorrow and give you the money?’ And you better have it for him tomorrow, because I might not be around tomorrow. And you act scared, like I gave you a couple smacks, because that’s what I’m supposed to do. You don’t act right, I’ll stab you myself, because I put my ass on the line with him.”

This tough guy is practically licking my hand because of his fear of Mirra.

We go back in, and the guy goes right up to Mirra and says, “Tony, I’ll give you the money tomorrow, meet you anywhere you want, okay? Okay?”

“The kid convinced you?” (Mirra sometimes called me “the kid.”) “Tomorrow. Right here.”

I was always on edge with Mirra. He was always in arguments with somebody. You never knew what might set him off, turn him into a cuckoo bird. He had no real allegiance to anybody. He was always in trouble with the law, which gave him a bad reputation on the street. I didn’t want to get tied up with Mirra, because you never knew when he would go back in the can. He was almost fifty years old, and he had spent more than half his life in jail.

He was valuable for introducing me to people. He introduced me to his captain, Mickey Zaffarano. Zaffarano handled porn theaters and national porn film distribution for the Bonanno family. He owned several pornography movie theaters in Times Square and around the country. His office was at Forty-eighth and Broadway—Times Square—upstairs from one of his theaters, the Pussycat. Mirra had me drive him up to Zaffarano’s office a couple of times. Zaffarano also came down to Madison Street once in a while. He was a big, good-looking guy, tall and heavyset.

Zaffarano eventually got caught up in the FBI sting operation called “Mi-Porn” out of Miami. When the agents went up to his office to arrest him, he started running away through the halls, and in the course of his run he dropped dead of a heart attack.

Lefty Ruggierro had a little storefront social club similar to dozens of others in Little Italy. Coffee, booze, card tables, TV. Downstairs was another room for more serious card games. Members only. Men only. Associates of Lefty and the Bonanno family only. It was a place to hang out.

In the back of the room was a phone and table, a place to take bets. Lefty was a bookie. Sometimes Mirra wasn’t there and I would bullshit with Lefty, chat about sports and what teams were hot to bet on. I began placing a few bets on baseball and horses, and on football when the pro exhibition season started—$50 to $100 just to help me be accepted. We started to develop a relationship. Lefty started calling me Donnie instead of Don, and that’s what everybody called me from then on.

The daily routine at Lefty’s was not much different from what it was at Jilly’s in Brooklyn, except that it was more of a real social club, not a store. Guys talked about the sports book, the numbers business, who owed what to whom, what scores were coming up. They groused about money. It didn’t matter how much anybody made or anybody had; they always groused about it. They were always talking about squeezing another nickel out of somebody.

After about two weeks Lefty asked me how I made money. By then I felt comfortable, not like I was rushing anything, so I told him I was a jewel thief and burglar.

“My son-in-law Marco is in that line,” he said. “Maybe you guys can get some things going together.”

“I usually work alone, Lefty,” I said. “But if there’s a good score and I like it, that’s always a possibility.”

For a while it was like a testing period. I just bided my time and didn’t push my nose into anything. Lefty started hitting me up for loans every now and then. He needed to pick up some clothes or some furniture, or whatever. I would lend him $300, $125. Sometimes he’d pay me back a fraction of it. I never thought he needed the money. I knew it was part of the hustle. You squeeze money out from whoever you can. Also, my lending him money was an indication that I was making money. So as not to seem like a patsy, I’d never give him all he asked for. He’d say he needed $500, I’d give him $200.

“Donnie, I need that thousand we talked about. You gonna be able to come up with that thousand for me?”

“A grand’s a lot for me right now, Lefty.”

“Yeah, but, see, I gotta pick up seventeen hundred bucks worth of clothes from this guy. What I’ll do, you give me the thousand, I’ll pay you back two hundred on that three-fifty I owe you.”

That kind of cycle went on with everybody. It didn’t necessarily mean guys were broke. It was just that everybody did everything possible to avoid using his own money.

In those days I was still moving around. I would stop down at Lefty’s at maybe ten o‘clock in the morning, hang around the club for an hour or two, have some coffee, read the papers, listen in on whatever conversations were going on, listen to some of the betting action going on over the telephone in the back. Then I’d go to Brooklyn and hang around Jilly’s for a couple of hours. Then in the evening I would hook up with Mirra, maybe meet him at Cecil’s, and hit the night spots.

Lefty suggested I come down to the club some nights. There were crap games or three-card monte games in the neighborhood. Some of them were heavy-duty. There would be regular games in a couple rooms upstairs from Fretta‘s, the meat market on Mulberry Street. Or they’d move around to different empty lofts. They’d move the games every week or two, just to keep on the safe side. They were pretty safe, anyway, in that neighborhood, as far as trouble from the cops was concerned, but you didn’t want to shove it in anybody’s face. Mainly I’d just watch. Guys could be winning or losing $100,000. Too steep for me on an FBI budget.

Lefty ran the bookmaking operation for Nicky Marangello, the underboss of the Bonanno family. One day he asked me to drive him uptown, to an address on lower Fifth Avenue. “I gotta see one of my biggest bettors,” Lefty said. “This guy makes men’s clothes, mostly shirts, up on the fourth floor. He put down $175,000 this weekend. I gotta collect.”

I gathered that in this instance Lefty collected between $5,000 and $10,000. “That’s a good week for me with him,” Lefty said. “One week last season I dropped sixteen grand in football bets to this guy.” He began regularly having me drive him around to make collections and payoffs on the betting operation. Sometimes he would meet somebody at the Biondi Coffee House on Mulberry Street to pick up money to pay off the bettors. His fortunes varied widely in the betting business.

“Couple weeks ago I got beat thirteen grand for the week,” he said. “Last week I booked fifty-two grand and my losses were only seventeen-fifty.”

One afternoon he had to run off somewhere, and he asked me, “You want to handle the phone while I’m gone?”

So I started taking bets over the phone for Lefty.

Lefty was very different from Mirra. He talked a lot and was excitable. He had a big reputation as a killer, but on a daily social basis he wasn’t as likely to inflict damage. Lefty and Mirra were both soldiers but under different captains. Mirra was under Zaffarano (until he died). Lefty was under Mike Sabella.

Sabella owned a prominent restaurant on Mulberry Street, CaSa Bella. Occasionally we went there for dinner. Lefty introduced me to Sabella, a short, paunchy man with baggy eyes. “Mike, this is Donnie, a friend of mine.”

One time during the Feast of San Gennaro, Lefty and I and Mike Sabella were sitting in a club across the street from CaSa Bella, which Mike usually closed during the feast because he hated tourists.

Jimmy Roselli, the Italian singer, had his car parked out on the street. He opened the trunk, and it was filled with his records. He started hawking his own records out of his car trunk right there at the feast.

Mike couldn’t believe it. He went outside and said to Roselli, “Put the fucking trunk down because you’re fucking embarrassing me by trying to sell your fucking records here on the street!”

Roselli closed the trunk immediately.

“He’ll act different from now on,” Lefty says.

Nicky Marangello, the underboss, stopped by Lefty’s club regularly. Called Nicky Glasses or Little Nicky or Nicky Cigars, Marangello was a small man with slicked-back hair, thick glasses, and a sharp nose. He never smiled. Because of his thick glasses, he seemed always to be staring. Lefty introduced me to him. “Nicky, this is Donnie, a friend of mine.” I wasn’t invited to join in conversation, so I would walk away while they talked.

Marangello had his own social club, called Toyland. It was Mirra who first took me to Toyland, at 94 Hester Street, on the outskirts of Little Italy and Chinatown. Toyland wasn’t the same kind of social club as Lefty’s.

The first time Mirra asked me to drive him there, he told me, “Toyland is Nicky’s office. You don’t go there unless you’ve got business there, unless he wants you there, or somebody like me or Lefty sends you there. You don’t hang out there. Nicky is usually there from about twelve-thirty to about four or five in the afternoon, Monday through Friday. You take care of your business with Nicky and then you leave.”

On the door was “Toyland Social Club” in painted script, and under that, “Members Only.” The room inside had a few card tables, a counter, a coffee machine—it looked typical for the little social clubs all around the neighborhood that were hangouts for wiseguys and connected guys. But it wasn’t social. Guys talked to Nicky one at a time. Others waited outside.

That was where I first heard about the “zips.” Mirra pointed out some of the guys hanging around Toyland, and he referred to them as “zips.” He said the zips were Sicilians being brought into the country to distribute heroin and carry out hits for Carmine “Lilo” Galante, the boss of the Bonanno family. This operation, Mirra said, was strictly in the hands of Galante. The zips were effective because, although they were in the family, they were unknown in this country—no police records. They were set up in pizza parlors, where they received and distributed heroin, laundered money, and waited for any other assignments from Galante.

The zips, Mirra said, were clannish and secretive. They hung out mainly by themselves in the area of Knickerbocker Avenue in Brooklyn. They were, he said, the meanest killers in the business. Unlike the American Mafia, zips would kill cops and judges.

Two of those he pointed out were Salvatore Catalano and Caesar Bonventre. Bonventre was lean and stylish. Catalano was chunky and narrow-eyed.

This was the first solid information I got on what was going on with the Sicilians. We knew there were Sicilians showing up, some coming into the country legally, some smuggled through Canada. But we didn’t know who was behind it, or what these Sicilians were being brought in for.

It’s an example of the importance of intelligence information even when you’re not making a particular case at the time. I was then primarily intent on working my way into the Bonanno family. When I first came across the zips with Mirra, I didn’t even know what I was on to. I just picked up the information and passed it on. Several years later my information on the Sicilians was put together with other intelligence, and a full-scale investigation was launched. It resulted in the huge Pizza Connection case in New York in 1986—the largest international heroin-smuggling case ever.

Eventually Lefty started sending me to Toyland to report on weekly bookmaking operations to Marangello. There was no chitchat. I would deliver the figures, how much we won over the weekend, how much we got hit for, what the total “handle” was—the total taken in. Maybe I’d answer a couple of questions. Then I’d leave. But I noticed that Marangello was looking me over.

Other people were looking me over, too, though I didn’t know it then. In separate operations, both the New York Police Department and the FBI had Toyland and CaSa Bella under surveillance during this time for other investigations. I showed up in their surveillance photographs. They had no idea who I really was. The NYPD identified me as Don Brasco, an associate of the Bonanno organized crime family.

Lefty and Mirra had once been partners, but now they hated each other. Each of them saw me as a potential good money-earner, so jealousy developed.

“Why you so friendly with that fuck Lefty?” Mirra would ask me. “He can’t do nothing for you.”

“That Mirra’s a crazy rat bastard,” Lefty would say. “He’s nothing but trouble. You shouldn’t be spending time with him.”

It was a dangerous game, being in the middle between those two guys. With each of them bad-mouthing the other to me, and each wanting me to drop the other guy, I was in a squeeze, too much in the spotlight. Eventually I would have to choose.

Mirra was a better money-maker than Lefty. He told me that in the four months he’d lately been out of jail, he’d made more than $200,000. He roamed wider and had more varied contacts. But he was crazy. People around him acted like they were his friends because they feared him. But everybody hated him. Even Lefty’s captain, Mike Sabella, hated Mirra. Lefty wasn’t as volatile as Mirra and had more loyalty toward friends. Lefty also had good contacts. And I could see that Lefty commanded more respect from other wiseguys, because of his loyalty and the fact that he wasn’t so troublesome. I thought it would probably be more effective to concentrate on Lefty.

As it turned out, I didn’t have to choose.

One afternoon I walked into the club and Lefty was on the phone. “Hey, Donnie, somebody here wants to talk to you.”

I thought, Who the hell would be calling me down here? It was Jilly. “Lefty was asking me about you,” Jilly said. “I put in a good word.”

After the call I asked Lefty what that was all about.

“Jilly says you ain’t no leech. He says you keep busy and earn good, and nobody over there had to carry you.”

“So?”

“So I’m happy to hear it.”

A few days later he said, “Donnie, I put in a claim on you. I went on record with Mike and Nicky. You’re my partner now.”

“Hey, Lefty, that’s great,” I said.

“Now, Donnie, this means that you have to start really listening to me, going by the rules. I’m responsible for you. You’re responsible to me. I hope everything you say about yourself is true. Because if you fuck up, we’re both gonna go bye-bye.”

Suddenly everything was changed. I couldn’t be so loosey-goosey anymore, come and go as I pleased, pretend ignorance. I couldn’t make excuses about not belonging to anybody or not knowing the rules.

Lefty began what he called his “schooling” of me. It began right away and never stopped.

Lefty was fastidious. He told me to shave off my mustache and cut my hair. “No real wiseguys wear mustaches,” he said, “except some of the old mustache petes. You gotta look neat, dress right, which means at night you throw on a sport jacket and slacks.”

He told me I have to show respect to all family members. “That’s the most important thing,” he said, “respect. The worst thing you can do is embarrass a wiseguy. If you embarrass a captain or a boss, forget about it. You’re history.”

When you were around a captain or a boss, you didn’t speak or join in the conversation unless asked to.

“Now, when a wiseguy introduces you to another wiseguy, he will say, ‘Donnie is a friend of mine.’ That means Donnie is okay, and you can talk in front of him if you want, but he’s not a made guy, so you may not want to talk about certain business or family matters in front of him. That’s the way I introduce you, see. When a wiseguy is introducing another made guy, he will say, ‘He’s a friend of ours.’ That means you can talk business in front of him, because he’s a member of La Cosa Nostra.”

He told me that my activities had to be cleared through him. If I wanted to travel out of town, I had to get permission from him, and I had to keep in constant contact with him. Any proceeds I made had to be split with him.

“When you talk on the phone,” he told me, “you don’t talk direct about what’s going on. You talk around it, throw me a curve—just give me a hint about what you’re talking about. Because all the phones are tapped, you know.”

Like most mobsters, he was paranoid. “There’s agents everywhere,” he said. One time we were out on the sidewalk and he pointed down the street at a school. “See up on that roof there?” There were some TV antennas. “Agents put them up there. If they’re listening, they can hear every fucking word we say.”

You didn’t use last names unless absolutely necessary.

You didn’t mess with a wiseguy’s wife or girlfriend.

You always took the wiseguy’s side of a dispute with a non-wiseguy, even if the wiseguy was wrong.

Since I was now a connected guy, but not a wiseguy, I was not to argue or talk back to a wiseguy or to raise my hands to one. “When you’re not a wiseguy,” Lefty said, “the wiseguy is always right and you’re always wrong. It don’t matter what. Don’t forget that, Donnie. Because no other wiseguy is gonna side with you against another wiseguy.”

You observed the code of silence about the family. You didn’t put business “on the street.”

“You keep your nose clean and don’t fuck up,” he said, “and obey the rules and be a good earner, maybe you’ll get proposed for membership one day.”

Occasionally I was still spending time with Tony Mirra. Lefty whined about it, but as long as I split with him any proceeds of anything I did with Mirra, it was okay. Mirra was a late-night person, anyway, and Lefty was not, so I could manage them both. I didn’t want to cut myself off totally from Mirra unless and until I had to.

I was out bouncing with Mirra and a couple other wiseguys and their girlfriends. About four in the morning we went for breakfast. Suddenly Mirra turns obnoxious with the waitress, bitching about cold eggs and bad service. He cranks it up, getting nastier, making a scene.

Finally I say quietly, “Hey, Tony, it’s not her fault, she’s doing the best she can.”

That sets him off worse. He leans across the table and says, “You shut the fuck up. You don’t ever tell me what to say or not to say or how to act.”

“I don’t mean to, Tony. I just thought maybe you could ease up on her.”

Then he launches into a tirade in front of everybody. “You fucking jerk-off. You’re nothing, you know that? You got no power, you got no say. You think that fuck Lefty’s gonna protect you? You’re with me here, and you keep your fucking mouth shut if you want to keep breathing.”

I had to shut up because it was only going to get worse and go totally out of control. So I say, “Tony, you’re right. I probably was out of line.”

But inside I was seething. I’m on the job here at four o‘clock in the morning doing the best I can in my role, tired, missing my family, and I have to take this shit in front of people in a restaurant. I had never allowed anybody else to talk to me like that in my life.

When I got back to my apartment, I grew angrier about it. I knew the rules: If you’re not a wiseguy, you don’t talk back to a wiseguy, you don’t raise your hands to a wiseguy. But this wasn’t the first time he had dressed me down in front of people. I couldn’t let him continue to walk all over me just because he was Anthony Mirra.

I risked seeming like a patsy. This guy is talking to me like I’m a nitwit, and on the street you have to command a measure of respect no matter who you are.

But I had to be careful, because I was still consolidating my position with the Bonanno family, and any wrong move could blow all the previous months of effort. I had to straighten this situation out with Mirra, but it had to be just him and me, not in front of witnesses. I had to let him save some face.

I had to confront him and hope I could keep the situation under control. If it came to a fight, I was a loser either way. If I beat him, I’m a loser because for sure I’m going to get whacked by him sometime soon afterward. If he beat me up or cut me, then I would be a pussy in everybody’s eyes.

The next day I find him at his luncheonette on Madison Street. I say, “Tony, let’s take a walk.”

We walk up Madison Street. Outwardly I’m casual. But inside the adrenaline is pumping. There are people on the street, but that won’t help me if it goes bad. I am thinking about his temper and his knife.

I say, “Tony, I realize that you’re a wiseguy and I’m not, and that you command a certain respect for being a wiseguy.”

“Yeah,” he says.

“But I’m telling you now, don’t ever embarrass me in front of people again. Because I’m not just some fucking Joe Scumbag on the street. And if you keep doing it, one of these days, Tony, I’m gonna get you for it. And it’ll be when no one else is around.”

I wait for his reaction. We keep walking.

“Ah, you’re okay with me,” he says at last. “I like you.”

“Then don’t embarrass me. As far as I’m concerned, right now everything’s forgotten, nothing ever happened, we have a new start.”

That was the end of the conversation. He peeled off and went back to his luncheonette. He never mentioned anything about it, but there was an edge between us after that. He never forgot.

He offered me a job. Mirra wanted me to handle his slot-machine route, make the collections. “I’ll give you three hundred bucks a week,” he said.

That was strange. I knew he respected my abilities, but I couldn’t be sure what was cooking in that off-the-wall mind of his. There was no way I could take the job, because if I did, I’d be married to the guy, under his thumb, like an errand boy—which is what everybody was to Mirra. I’d be looking over my shoulder all the time.

I said, “Look, Tony, I’d be happy to help you now and then, you know. But I got some things going, and three hundred a week just wouldn’t be worth my while to get tied up.”

“Fine,” he said.

I told Lefty about the job offer. “You did the right thing, Donnie,” he said. “Anybody that gets hooked up with that cocksucker ends up getting fucked over or whacked.”

Not long after that, Mirra went on the lam. He snuck out of town in a Volkswagen. He was wanted by the state on another narcotics rap. They caught up with him after about three months, and Mirra was back in the can.

He was sentenced to eight and a half years in New York’s Riker’s Island Prison. Lefty said, “See how tough he is with those niggers out there.”

I was through with Mirra—for a while.

Besides the bookmaking operation, there were all kinds of scams and schemes around. Little ones and big ones. These guys might pull off a $100,000 score one day, rob a parking meter the day after. Anything where there’s a dime to be ripped off.

The key was in the number of scams. Two hundred dollars isn’t a lot, but if you’re hitting up fifty scams for $200 apiece, you’re making some money. We had counterfeit credit cards and stolen credit cards. You could always beat those once or twice before it got hot. They would go in with these cards and buy a lot of electronic equipment that they could sell.

A guy named Nick the Greek regularly supplied Lefty with manifests of cargo ships docked over in Jersey. Lefty would have stuff stolen to order. He showed me the manifests so I could check through them and see if I wanted to buy anything—radios, luggage, clothes. He and his crew could provide all kinds of phony documents. He had a guy in the Department of Motor Vehicles who supplied him with blank drivers’ licenses. You just had to type in the information. One guy paid Lefty $350 for six phony New York State drivers’ licenses and six phony Social Security cards.

For settling a beef between owners of a company at the Fulton Fish Market, Lefty and two of his associates were given twenty percent of the ownership, plus a salary of $5,000 a month. “It’s a shame,” he told me after meeting with the other owners at his club, “that my shares couldn’t be put in my name.” Wiseguys didn’t like to show income or ownership of anything. The cars they drive are almost always registered to somebody else. Lefty didn’t file tax returns.

A typical scam was how we worked cashier’s checks. Lefty told me he had access to cashier’s checks from a bank in upstate New York. “We got a vice-president up there that will authorize cashing the checks when anybody calls him up,” he said. The checks would be used to “buy” merchandise, which we could then resell.

He introduced me to a guy named Larry, who used to own a bar on Seventy-first Street. Larry was the contact on the deal. Larry said he had sat down with some friends of his in the banking business and figured out the best way to work the scam.

He had the stamp machine to certify the checks. He had several guys besides me to pass them. He had eight checks and provided us with a list of eight names, which were the names to be used on the checks. He provided New York State drivers’ licenses and Social Security cards for IDs on the eight names. Bank accounts had been opened in these names. There just wasn’t money in them to cover these bogus checks. When a business would call the bank for verification, giving the name on the check, this vice-president would okay the check. In order to pull this off before the bank caught up with the scheme, all the checks had to be cashed within one week. If we worked it at maximum efficiency, the checks could be worth $500,000.

Larry had a list of stores where we could buy merchandise with the checks, stores innocent of the scheme but places Larry knew could accept cashier’s checks. I was supposed to use the name and ID papers of “John Martin,” and be working for a company named Outlet Stores. In case the merchant wanted to verify that Outlet Stores existed, Larry gave me a number for him to call, where someone would answer “Show-room, Outlet Stores.”

I was to go into a store and select the merchandise I wanted to buy, then tell the merchant I would be back with a cashier’s check in the proper amount. Then I would call a number to reach a guy named Nick. I would give Nick the name of the store and the amount, and Nick would fill in the check and stamp it “certified.”

The guys passing the checks would be spread out in the New York-New Jersey area. I was directed to go to a certain store on Orchard Street, in New York’s lower east side, and buy around $4,000 worth of clothes.