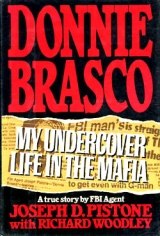

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

I went to the store, picked out $2,660 worth of men’s clothes, and told the salesman I would be back shortly with a certified check. I left the store and called Nick.

Nick said to meet him at Lefty’s club in an hour. Nick handed me the check, marked with a blue “certified” stamp.

We went back to the store, picked up the clothes, and loaded them in the trunk of his car. Other of his guys would take care of selling the stuff from all the purchases of all the guys.

A week later Larry met me at Lefty’s. He said that he had had trouble getting rid of the clothes I had bought and that he had finally gotten $1,100 for them. After expenses he had $600 left. “I had to give the banker his cut, see,” Larry said. “And then the other two main guys, they hammered me for a bigger cut. You know.”

Lefty was disgusted. “Forget about it,” he said. “Just give us what you got for us, and don’t come back around here no more.”

Half of the $600 was Larry‘s, so he gave me $300. I had to split my end, as always, with Lefty.

I came out of this whole big deal with $150, which I passed on to my contact agent.

After the operation the FBI reimbursed the stores.

Lefty introduced me to a guy named “Fort Lee Jimmy” Capasso (because he was from Fort Lee, New Jersey), a capo in the Bonanno family and a partner of Nicky Marangello. One day I was waiting around in front of Toyland when Fort Lee Jimmy came over and said, “Donnie, like to talk to you.”

He was in his fifties, always seemed like a decent guy.

He took me aside. He says, “Donnie, you seem like a pretty sharp guy. I just want to give you a piece of advice. This business we’re in, you get old fast, and a lot of things you do now you can’t do when you get older. Lot of these guys you see around make a lot of money, then they get older, fifty or sixty, and they’re broke because they didn’t save anything. And now they can’t make so many good moves anymore. So my advice is, Donnie, find somebody you can really trust. Every time you pull a score, take some of that money and give it to that friend and have them keep it for you. And make the rule with that friend that he won’t give you any of that money until you like retire. You can’t go to this guy tomorrow and ask for a grand or two, because he won’t give it to you—that’s the rule you’ve set up. Just keep doing that over the years, so when you get older and can’t be out stealing every day, you got yourself a nice little stash. You don’t have to worry about being old and broke, like a lot of these guys.”

He was recommending a little Mafia IRA, back in 1977.

8

LEFTY

Like most wiseguys, Lefty Guns Ruggiero still lived in the same neighborhood where he was born and raised.

He lived in a big old apartment complex called Knickerbocker Village on Monroe Street, a few blocks south of Little Italy. A lot of wiseguys lived in there, including Tony Mirra. Lefty invited me up there often.

Lefty’s apartment was a small one-bedroom on the eighth floor, overlooking the interior courtyard of the complex. He loved tropical fish and had several tanks of them. He had a big color TV and a VCR, and a cable connection into which he had tapped illegally, like all the wiseguys, so it was free.

He didn’t have air-conditioning. Lefty hated air-conditioning. On the hottest, most humid days, he wouldn’t let me turn it on even in the car. He chain-smoked English Ovals, which made the air everywhere he was worse—especially for a nonsmoker like me.

He was a great cook, any kind of food. I would go over there to eat a couple of times a week.

Lefty had been divorced for a long time. His girlfriend, Louise, was a nice girl from the neighborhood. I got along good with Louise. She put up with a lot. Lefty had no sensitivity and sometimes treated her badly, just like he treated everybody else. But at the same time he was protective of her and quite faithful. She had a full-time job as a secretary.

When Louise’s mother died, she asked me to come to the wake. I didn’t know her mother, but I was complimented to think that Louise liked me well enough to include me. I remember it was raining like hell when I went to the wake. It was dreary and sad, and put me in a strange mood, sharing this kind of time with somebody who thinks you’re somebody else.

You develop feelings for people, even in this job. It’s easy to accept deceiving the badguys, because that’s the game. Knowing that for five or six years you’re deceiving others in their world who are not badguys, who don’t know what’s going on, who just happened to be born to or married to badguys, that’s tougher on your mind. Some of those people develop feelings for you too. While you are allowing this to happen, you know that in the end, they are going to be hurt by what you are doing. And they don’t even know who you really are.

Lefty had had four grown kids. I got quite close to Lefty’s kids, really became a friend to them. They would come to me with their problems. His youngest daughter, in her mid-twenties, lived with his ex-wife in the building and worked at a hospital. She was a hard worker. Every year she had a booth at the Feast of San Gennaro, where she sold soft drinks and fruits. His son, Tommy, who was about twenty-eight, also lived in the building. He was a thief and had done some work for the family. Basically he was a free-lancer. But he also had problems with heroin. He was an on-and-off junkie.

Lefty was continually asking me to talk to Tommy, get him straightened out. He wanted me to help keep him off drugs and to get him to settle down to work. Sometimes Tommy and I would be in Lefty’s club in the early afternoon watching our favorite soap operas, like All My Children. Lefty would come in and see that and throw a fit. “Turn off them fucking soap boxes!” he would bark. “You should be out stealing and looking for business. Come on, Donnie, get Tommy busy out on the street.”

Two of Lefty’s daughters were married to wiseguys. One had the misfortune to be married to Marco.

I met Marco at the Bus Stop Luncheonette, Mirra’s place. Besides being a jewel thief, Marco was supposed to be an expert safe-and-lock man. He was also a drug dealer and a loudmouth. Other than a few conversations about jewels, I never had much to do with Marco. He lived a flashy life, vacationed in Florida where he had a big boat. He boasted that he could move all the dope that anybody could provide him with.

When I met Marco, he was worried about his partner, Billy Paradise. “Billy has turned stoolie,” Marco said. “Billy could put me away twenty-two times if he ratted me out about the jobs we pulled.”

Lefty was also worried about Billy Paradise. “We gotta think about having that guy whacked,” he said.

“I’d like to take him on my boat and throw him to the fishes. I ever tell you that story, Donnie, about the guy that thought I was gonna whack him on my boat?”

“No.”

“One day I asked this guy to come out with me in my boat, you know, in the East River, my speedboat. He came along, but he kept watching me, wouldn’t turn his back to me. Finally I asked him what the hell was the matter. He said he was afraid that I thought maybe he had turned stoolie and I was gonna shoot him and throw him overboard. I said, ‘You dumb bastard. If I wanted you whacked, I wouldn’t have bothered bringing you out in my boat. I would have hit you downstairs at the club while you were playing cards and rolled you up in a rug and dumped you in the river right at South Street. That’s what we do with stoolies,’ I told him.”

He was looking at me. I didn’t know if he was just telling me a story, or if he was giving me a message about what happens to informants.

“Well, I hope this guy Paradise don’t rat anybody out,” I said.

One day Marco just disappeared. The word was he got into skimming drug profits that were supposed to go to the organization. He was never found. Word on the street was that the contract had gone to Lefty, to whack his own son-in-law. But Lefty never said anything about it.

Louise knew what kind of business Lefty was in, that he came and went when he wanted to, like all the wiseguys do. They seemed to have a comfortable relationship. Lefty talked openly in front of her, but without swearing. That’s a thing about wiseguys. You can go out and kill somebody, but don’t swear in front of a female. And if a female swears, she’s a puttana—a whore. “If Louise said ‘fuck,’ I’d throw her out the window,” he said.

In September they decided to get married. Lefty asked me to be best man. The wedding was at City Hall. They were all dressed up. Lefty was so nervous that he forgot to pick up the license. The ceremony was at five P.M., and the license bureau was closed. The judge got his clerk to go down and get the license.

I gave them $200 as a wedding gift. We went to CaSa Bella to celebrate. Maybe ten people. Mike came over and sat down with us to have a drink. Then we went uptown to Château Madrid, Lefty’s favorite place, where we saw a floor show with flamenco dancing.

“You ever do a hit on anybody, Donnie?” Lefty asked.

“I never had a contract, if that’s what you mean. I killed a couple guys. One guy in a fight, another guy that fucked me out of a score and we got into a beef.”

“That ain’t a hit.”

“If you kill somebody, you kill somebody, what’s the difference?”

“No, Donnie, you don’t understand. It ain’t that simple. That’s why I gotta school you. Hitting a guy on a contract is a lot different than whacking a guy over a beef. On a beef, you got a rage about the guy. But on a contract you might have no feelings one way or another about the guy, it might not even concern you why the guy’s getting hit. You got to be able to do it just like a professional job, with no emotion at all. You think you could do that?”

“I don’t see why not.”

“Yeah, well, we’ll see. Lot of guys think it’s easy, then they freeze up and can’t do it. Next time I get a contract, I’ll take you with me, show you how to do it. Generally you use a .22. A .22 doesn’t make a clean hole like some bigger calibers. Just right behind the ear. A .22 ricochets around your skull, tears everything up. Next contract I get, I’ll take you along.”

What would I do if and when that situation came up? As an agent, I can’t allow a hit to go through, can’t condone it, certainly can’t participate in it, if I know it’s going to happen. But I could find myself in the situation all of a sudden. I didn’t always know where we were going or why, and it wasn’t appropriate to ask.

If a hit is going down and I’m on the scene, do I risk trying to stop it and maybe getting killed myself? My decision was that if it came to it, if the target was a wiseguy and it came down to whether it was him or me, it was going to be him that got whacked. If it was an ordinary citizen, then I would take the risk and try to stop it.

By midsummer of 1977, I was really becoming accepted and trusted and could move around easily. I knew most of the regular wiseguys down on Mulberry Street, not only Bonannos but guys from other crews. I was given the familiar hugs and kisses on the cheek that wiseguys exchange. I could come and go in any of the joints I wanted. I could move in and out. A lot of times we would hang out at 116 Madison Street, the Holiday Bar, a place so dingy that I would only drink beer or club soda out of a bottle, I wouldn’t touch a glass. Social clubs, coffee shops, CaSa Bella. We would hang around, play gin, and everybody would tell war stories to each other and bust balls.

I met guys like Al Walker, Tony Mirra’s uncle, whose real name was Al Embarrato. Mirra’s nephew, Joey D‘Amico, who went by the name of “Joe Moak.” Big Willie Ravielo who ran the numbers in Harlem for Nicky Marangello; Joey Massino, a beefy, broad-shouldered, potbellied man who was rising quickly through the ranks; Nicky Santora, who had served time for bookmaking and aspired to be a partner with Lefty; the Chilli brothers, Joe and Jerry.

And then there were Frankie Fish, Porkie, Bobby Smash, Louie Ha Ha, Bobby Badheart (because he wore a pacemaker), Joe Red, and so on.

Real names didn’t mean anything to these guys. They didn’t introduce by last names. I knew guys that had been hanging out together for five or ten years and didn’t know each other’s last names. Nobody cares. You were introduced by a first name or a nickname. If you don’t volunteer somebody’s last name, nobody’ll ask you. That’s just the code. The feeling is, if you wanted me to know a name, you would have told me.

The reason I knew guys’ last names was through our own FBI identification. I always tried to get some kind of ID on everybody that came through the scene, even if it was just a nickname. You never knew who might turn out to be important somewhere down the road, or in some other investigation.

I told Lefty I had a girlfriend in Jersey and that sometimes when he called my apartment and I wasn’t there, I was probably with her. Over a period of time the topic of my girlfriend came up a lot. I never volunteered a name. He never asked what her name was. Nobody did.

All through 1977, Lefty didn’t tell me his last name. I knew his name, of course, but he didn’t tell me. I didn’t tell him mine. I knew him as Lefty and Bennie. He knew me as Donnie. I used to go to his house on Sundays or at night and eat with him and Louise. I’d watch TV with them. I’d lie on the couch and fall asleep. He never told me his last name or asked me mine. The first time we traveled together and checked into a hotel, he said, “What name do you want me to put down for you?” That was how he found out my name was Brasco. And the first time I had to check him in someplace, that was when I asked him what his last name was.

All during this time I was passing on to the Bureau more intelligence about the structure of the Bonanno family and other families: how they operated, who was who and what rank, information on the Mafia nationwide, intelligence we’ve never had before from an agent on the inside. I was continuing to pick up information on the Sicilian mafiosi that were being brought over, how Galante and Carlo Gambino were collaborating on setting them up in pizza-parlor businesses in the East and the Midwest and leaving them there until the bosses needed them to do something. How these “zips” were being used as heroin couriers and hit men.

To ease the tension I used to try to run every day, and lift weights at the health club in my apartment building. I didn’t know any wiseguys at the time who were doing that. It was okay, I was just considered a health nut. On most Sundays I would try to go to Mass. Wiseguys didn’t do that, either.

Lefty was treating me like we were pretty close. He saw me as a good earner. I didn’t portray myself as somebody having a big bank account or big business because I didn’t want to get tagged as a mark. I wanted to get tagged as a working thief. I portrayed myself just like they were—you make a score, you live good for two or three weeks, then you’re back to scrounging again. He saw just enough money come out of me to suggest that I could make a lot. He needed that, because he was in trouble.

“I owe a lot of fucking money,” he told me. “I’m in hock a hundred and sixty thousand to Nicky. I can’t get no place with that debt hanging over my head. It’s like I’m spinning my wheels. We gotta make some money.”

Unlike most wiseguys, Lefty had not served time in prison. He had been arrested many times for extortion and theft but had always beaten the rap. Lefty’s real problem was that he was a degenerate gambler. If he made $2,000 one day, he would blow $3,000 at the track the next day. I knew him to lose as much as $10,000 in one day at the track or an OTB (Off-Track Betting) parlor. If he went through that and had $2 left, he’d bet that too. He preferred bookies because at OTB, if you win, you pay them a percentage right off the top; with bookies you don’t pay them anything if you win, and they pay better odds than the state does.

I’m the world’s worst gambler. I couldn’t win at craps, at cards, or at the track. I wouldn’t bet on anything ever if it weren’t for this job. But Lefty was worse. He had no more skill, his luck was just as bad, but he was the typical gambling addict. The big killing was just around the corner.

Sometimes we’d pop down to Florida for a little vacation. We’d hit the dog tracks and the horse tracks. He didn’t know much about the dogs. We might win or lose $100 or $200. Mostly we lost. He didn’t know much about the horses, either. We didn’t get inside tips. Lefty would just handicap by the program.

One time we were at Hialeah and we went for the “pick six.” For the first five races we invested a couple of thousand on long shots and won every time. The sixth race was worth about $30,000 if we picked right. So we figured that in this last race we’d bet the favorite, to be safer. The favorite lost. So we blew a shot at $30,000.

His reaction was: “Finally we bet the chalk horse, the fucking horse loses. That other horse hadda come from nowhere. Thirty fucking thousand we coulda won.”

“Well, we only lost a couple grand,” I said. “Ain’t the question, Donnie. The point is, we had it right in our fucking hands!”

His problem was so bad that it had delayed his becoming a made guy. He told me that when I first met him, he wasn’t made yet, and that was because he hadn’t paid off his gambling debts. He whittled them down some, and because of that he was able to get made shortly after I met him, in the summer of 1977.

But now he was in hock again for this huge amount, and that meant that everything he made from the bookmaking or anything else, Marangello was taking Lefty’s piece right off the top to apply to the debt, and Lefty never had anything, except what he could hide. The nature of the game was that everybody always pled poverty, anyway, so you could never be sure whether Lefty was broke or not.

I brought around just enough money to convince Lefty that I was a good earner, with potential that he could develop. Together we could make our fortune, as Lefty saw it.

He encouraged me about my future in the mob.

“The thing is, Donnie, you gotta keep your nose clean. You gotta be a good earner and don’t get into trouble, don’t offend, don’t insult anybody, and you’re gonna be a made guy someday. Now, the only thing is, they might give you a contract to go out and whack somebody. But don’t worry about it. Like I told you, I’ll show you how. You got the makings, Donnie. You handle yourself right, keep your nose clean, keep on the good side of people, I’ll propose you for membership.”

Lefty says, “Come on, we got to go up to Sabella’s.”

It’s a hot July night. We go to CaSa Bella but we don’t go in. There are five or six other guys standing outside on the sidewalk, guys I recognize as being under Mike Sabella. We stand on the sidewalk with these other guys.

I ask Lefty, “Why the hell are we standing here?”

“We’re out here to make sure nothing happens to the Old Man. He’s in there.”

The Old Man is Carmine Galante, the boss of the Bonanno family. He just recently got out of prison. I look in the restaurant window and I can see him sitting at the table reserved for big shots; he’s hawk-nosed, almost bald, has a big cigar in his mouth. Sabella and a few others are seated with him.

“What’s the big deal?” I say. “What’s gonna happen to him?”

“Things are going on,” he says. “There’s a lot of things you don’t know, Donnie. Things I can’t talk about.”

“Well, why can’t we go inside and make sure nothing happens to him in there, where at least we could sit down?”

“Donnie, Donnie, listen to me. You don’t understand nothing sometimes. In the first place, Lilo don’t sit down with anybody except captains or above—bosses. He don’t sit down with soldiers or below, like me and you. He doesn’t have anybody around him except people he wants. You can’t even talk to this guy. You got to go through somebody higher, somebody that can talk to him. He don’t want nobody in the restaurant except those people in there, and that’s it. ”

“Okay, if you say so.”

“You don’t know how mean this guy is, Donnie,” Lefty goes on quietly. “Lilo is a mean son of a bitch, a tyrant. That’s just me telling you, it don’t go no further. Lot of people hate him. They feel he’s only out for himself. He’s the only one making any money. There’s only a few people that he’s close to. And mainly that’s the zips, like Caesar and those that you see around Toyland. Those guys are always with him. He brought them over from Sicily, and he uses them for different pieces of work and for dealing all that junk. They’re as mean as he is. You can’t trust those bastard zips. Nobody can. Except the Old Man. He can trust them because he brought them over here and he can control them. Everybody else has to steer clear of him. Theresalot of people out there who would like to see him get whacked. That’s why we’re here.”

This happened a few times, Lefty and I going down to CaSa Bella to stand guard outside while Carmine Galante held meetings inside. Lefty was nervous, out there on the sidewalk. He and the other guards, except me, were carrying guns in their waistbands under their shirts. He watched people and cars going by. He watched windows across the street.

I wasn’t comfortable, either. Here I was, an FBI agent, worried about getting whacked on this sidewalk on Mulberry Street because I was trusted enough by these mobsters to be standing guard over the feared boss of the Bonanno family.

Every few days I would call in to my contact agent. There was a special telephone line installed in the New York office for my calls only, and it would be answered by my contact agent. I would give him a rundown on what had been going on and what was coming up. Sometimes, for other operations, he would ask me to find out what’s going on at this or that club, who’s showing up or what’s being discussed. If I needed anything checked out—like a name or what a guy was into—he would take care of that for me. Any information I gave him that was noteworthy and that might be useful as evidence would be typed up as what we call “302s.” Once in a while the contact agent would bring along a handful of these reports for me to initial.

Once or twice a month, depending upon my circumstances, I met with a contact agent to get an envelope of cash for me to live and operate on. We would meet only briefly, usually just a couple of minutes. Often we met at museums—like the Guggenheim or the Metropolitan on Fifth Avenue. We would just be browsing, looking at the exhibits, he’d slip me the money. Sometimes we met on a bench in Central Park. Sometimes at a coffee shop.

We were approaching the end of 1977, and I had been undercover now for more than a year. The Bureau was about to close down the “Sun” part of Sun Apple in Florida, just settle for what Joe Fitz had been able to get so far without risking him down there any longer for minimal gains.

Once in a while my supervisor asked me how I felt, if I wanted to go a little longer. I felt fine. I wanted to keep right on going.

There were a couple of new considerations. I now had a good foothold with Lefty and the Bonannos. I was in pretty solid. The Bureau had started other undercover operations around the country. We could use my new mob credentials to establish credibility of other undercover agents in some of these other operations. I could be brought around to vouch for these other agents—attest that they were “good” badguys. Badguy targets of these other operations could check me out: I’m a friend of Lefty’s in New York.

It would be easier for me to do this if I wasn’t based in New York City, under Lefty’s thumb and eye on a day-to-day basis. If I moved someplace else while remaining Lefty’s partner, I could more easily slip around to these other undercover operations without having to ask permission to go out of town and without having Lefty knowing of my every move and questioning me about it. Also, conceivably I could bring Lefty out to these other operations, introduce him, hope that he might horn in, establish a link with the Bonannos that would form a conspiracy under the law.

I could still regularly come back to New York for two or three weeks at a time, continue to develop my association with Lefty, and maintain the partnership.

The other consideration was my family. Earlier I hadn’t been too concerned about protection of my family. I would get home to our house in New Jersey maybe one night every ten days or two weeks. I was always careful and covered my tracks. But by the fall of 1977, I was beginning to think that if I continued to get deeper into the mob, eventually my family was going to have to move away. There was always the chance of momentary carelessness that could be disastrous. I knew I was under surveillance by cops because I was being followed. Three or four times I was stopped and searched—for no apparent reason. Suppose I didn’t shake them off my tail sometime and they followed me right to my house? Or what if Lefty or some other wiseguy decided to follow me?

It was time to get my family out of there. That would eliminate that problem. And if I was going to be transferred out to another area, we might as well combine the two.

Through December and into January, I discussed this with my supervisor. He took the matter to headquarters. It was a pretty simple proposition. We decided to make the moves on February 1.

My family was used to moving. We had already moved four times for my job. But now my daughters were at an age where attachments to friends and boyfriends were more important. We had close relatives in New Jersey. When we moved back there for my earlier transfer to the New York office, we had supposed we would be staying. Nobody wanted to move again. My wife understood that it was necessary, without knowing the details. We didn’t have big discussions about it, because I didn’t present it as a choice. I was being transferred. They still didn’t know how deeply involved I was with the Mafia. They didn’t know the move had to do with their safety.

The FBI then had fifty-two offices throughout the country. They gave us the choice of five areas in which to relocate. As far as my work was concerned, where we lived didn’t matter because I would still be assigned to the New York case, and otherwise I would be roaming to different parts of the country. My wife and I picked an area.

I managed to get home late Christmas Eve and spend most of Christmas Day at home. In January, my wife and I took a trip to find a new house. We found one right away—smaller than our house in Jersey but in a pleasant neighborhood. The next week we put our New Jersey house up for sale. I had a friend who was a mover. I told him we needed to move and that he shouldn’t talk about it.

There were lots of family tears shed over the move. Nobody wanted to stand in the way of the work I was doing, but neither did anybody really know what I was doing. Had my family known more, they might have been more tolerant of my situation. But if that would have decreased the weight on me, it would have been at the cost of more fear to them.

For me and my colleagues in the Bureau, there had been no expectation that this job would go on so long. Now there was no guess at how long it would continue. What started with the idea of getting to fences had become penetrating the Mafia in Little Italy and now had evolved to me representing the mob in other places. It could have been mind-boggling except for the fact that we didn’t know where we were headed, and so we had no good perspective on where we were. The only certainty was that to continue at all I had to continue full-out. Donnie Brasco had the momentum.

The FBI had a couple of situations in San Diego and Los Angeles that they wanted me to look into. I told Lefty I had decided to go back to California—where I had supposedly spent a lot of my earlier jewel-thief life—for a while. “You know, Left,” I said, “I’m not making all that much money here right now. Why don’t I go out there and start making some good scores, you know, and come back and forth? You could even come out there, hang out for a couple weeks, see if we couldn’t get something going.”

He thought that was a good idea. So I took off for California.

In L.A., we had an agent going by the undercover name of Larry Keaton. Larry was a longtime friend of mine. He was trying to get in tight with some thieves who were engaged in all kinds of property crimes: thefts of stocks and bonds, checks, cars—the whole spectrum. These badguys were not necessarily Mafia, but some of them were ex-New Yorkers, and naturally they were respectful of wiseguys and connected guys.

They liked to hang out at a particular restaurant, and Larry would mix with them, trying to get in deeper. It happened that a bartender from a New York restaurant came out on vacation, and he hung out at this L.A. restaurant and was friendly with some of these badguys. Larry didn’t know anything about this bartender. He thought maybe he was a badguy too. Since the bartender was from New York, Larry thought it was just possible I might know him.

It so happened that I did. It was a coincidence that on occasion Lefty and I went to La Maganette, a restaurant on Third Avenue and Fifty-fifth Street—not a Bonanno hangout, just a place where he and I and a couple other guys would go have a couple drinks and eat. We got to know this bartender, Johnny. Johnny wasn’t himself a badguy, wasn’t into anything, but like a lot bartenders, he knew who was who. He knew who Lefty was, and that as Lefty’s partner I was a connected guy. So this was a chance for me to give Larry some credibility with these badguys.

I went to this L.A. restaurant where Larry was hanging out and saw Johnny there. “Hey, Johnny,” I said, “how you doing?”

“Donnie, how you been? What’re you doing out here?”

“Hanging out, looking around.” Larry was in the group, so obviously he had already met Johnny. “I see you know Larry here. Larry’s a friend of mine. We may be working on a deal together.”