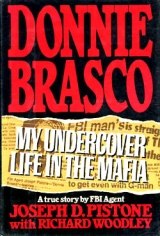

Текст книги "Donnie Brasco: My Undercover Life in the Mafia"

Автор книги: Joseph D. Pistone

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

3

PREPARATIONS

The FBI was finally thinking about getting into long-term undercover operations—long—term being, say, six months. Our success in the heavy-equipment operation helped convince people that using an agent this way, instead of just turning an inside guy into an informant, was effective.

My supervisor in New York, Guy Berada, who has since retired, wanted to get another long-term undercover operation going. He was in charge of the Truck and Hijack Squad, the squad I was assigned to.

Beginning in the spring of 1976, we had meetings and bull sessions and came up with the idea to infiltrate big-time fences—high-echelon dealers in stolen property who were associated with the Mafia. I was a natural link for the hijack squad. You get a report of a hijacking, you investigate it, find out who pulled the job, where the drop was, and who was fencing the load. Our goal was to go strictly after the upper-echelon fences, those who more often than not dealt with the Mafia, the outfit with the money, the know-how, and the connections to distribute the stuff further. Some of these fences owned restaurants or bars or stores; some were actual Mafia members—wiseguys, themselves.

It was decided to make it a one-man undercover job. I was picked because I had just come off the other successful operation, because I knew about hijacking, because I was familiar with the street world.

And not least because I was Italian. That would help me fit in with the types we would be investigating, because if they were not themselves Italians, the people they were dealing with were.

The idea was: You bust the fences, you wound the Mafia. That was the extent of our aims in the beginning, just to get the fences. Having decided on that, though, you don’t just walk out the door and begin work undercover. It took months of preparation, both for me and for the bureaucracy.

Eventually we had to sell the idea upstream, to Washington, to the brass at FBI Headquarters. In order to do that we had to have everything calculated—money, time, targets, probabilities for success. Long-term undercover operations were so new to the FBI that there wasn’t even a formal set of guidelines issued for undercover agents and their supervisors to go by until 1980, years later. It was pioneer territory, and you had to sell the plan well.

Just launching work on the proposal was exciting for me. I was in on the ground floor with the new long-term techniques. And it was targeted toward the mob, which intrigued me. We had new legal tools to use against organized crime. In 1970, Congress passed the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, which everybody refers to as the “RICO” statutes. For the first time we could go after “an enterprise” engaged in a “pattern of racketeering.” If we could show people involved in an organization whose purpose it was to commit crimes, we didn’t have to show that each member of that organization actually committed each crime.

We had the law we needed against the Mafia.

In this case, with a new type of undercover operation, I and the supervisors would be able to plan and steer the operation the way we wanted it, doing the thing ourselves without a lot of help or intervention from anybody else.

Berada was at that time one of the most imaginative supervisors. We had to get some good targets, and it had to be a feasible plan to sell to headquarters, something that would work, because like most bureaucracies, most people in ours didn’t want to put their necks on the line for something new and risky.

There was a lot of research to do before I could go undercover. Even the research was done discreetly. Only four or five people were involved in the entire matter. In the beginning only my supervisor, Berada; the Special Agent in Charge of the Criminal Division of the New York Office, Ted Foley; and the guys who would be my case agent, Joe Connally, and my contact agent, Steve Bursey, were in on it. I went through old, closed files, old reports, and talked to guys who were on the squad, guys I could trust, pumping them for all the information we could get on the fences that we were targeting. For the most part we knew who the fences were. It was just hard to get anything solid on them. So now, for the first time, we would try to plant one of our own men—me—to live and work among them. I gathered names, looked at mug shots. We wanted to know who their mob associates were, who the hijackers were, where they hung out, where they worked out of, what their habits and personalities were, what they looked like—anything that might help me navigate in their world.

In developing the plan and the proposal, there was a handful of people involved, from both New York and Headquarters. Eddie O‘Brien was the supervisor at Headquarters who handled undercover work in its infancy. For the proposal we identified some targets that were top fences, and some areas of the city that I would be going into, such as Little Italy in Manhattan and certain parts of Brooklyn, and restaurants and clubs where I might hang out. We left enough leeway so that in case we got other openings, we could take them.

It occurred to us to duplicate the New York plan in Miami, with another agent, the two to work in conjunction with each other. Miami had a lot of wealthy residents and vacationers, and a lot of con men and thieves who were specialists in jewels and stocks and bonds. So there were also a lot of big-time fences who dealt with the Mafia. We could target those fences down there as well, and the agent assigned to that end and I could back each other up.

The Miami office liked the idea. Berada and I went down to help them design the same type of proposal that we had for New York.

Then he and I discussed who I would feel comfortable with as the undercover agent in Miami. Anytime you’re working undercover, who you bring into the operation is a crucial choice. It has to be somebody you can trust with the job and your life.

At that time I didn’t know anybody from the Miami office who was available. The guy I decided on was a friend whose undercover name was Joe Fitzgerald. He was from Boston, stood about 6’5”, was a former defensive end for Boston College. I picked him because he was a good bull-thrower, sharp on his feet, and could really handle himself. He was basically a street guy. He had been in Miami enough to know his way around. So we brought Joe Fitz down to Miami and filled him in on the whole operation, and he accepted the job.

We would launch the two operations together, and the code name for the tandem would be “Sun Apple.” Miami Sun, New York Apple.

Next thing we had to plan was me. I had to establish a new identity that would stand up under whatever kind of examination that could arise. On the street everybody is suspicious of everybody else until you prove yourself.

We made a list of things I needed for a credible background. First was a name. From the heavy-equipment operation I already had the kind of wallet fillers you need for identification—social security card, American Express card, and driver’s license (actually I had two driver’s licenses, one for Florida, one for New York). So it seemed easiest just to stick with the name Donald Brasco. Under that name I had established some background in California and Florida and made some good contacts. It would be easier just to continue that than to change everything.

But the very background that gave that name an advantage gave it its disadvantage. I wondered whether the publicity I had gotten in the Florida heavy-equipment trials would come back to haunt me. But I hadn’t run into any mob guys during that time, so far as I knew. I thought about it for a long time while we were arranging other things. Finally I thought, What the hell, I’ll go with it.

As Donald Brasco, I had to have a past. Not too much of a past. Like everything else, I wanted to keep it simple. You have to tell a lot of lies, anyway. The fewer you tell, the fewer you have to remember. In my undercover work I stayed as close to the truth as possible, whenever possible. For this particular aspect—where I came from—the less there was at all, the better.

My background was going to be that I spent time down in the Miami area and out in California, and that I was a jewel thief and burglar—and a bachelor.

We came up with the idea that I would be an orphan. Without a family it’s harder for people to check up on you. If you had a family, you would have to involve other agents to speak up for you as family members. If you’re an orphan, the only thing they can check on is if you lived in a neighborhood or if you have any knowledge of the particular neighborhood. I had knowledge of areas in Florida and California because I had done some work there.

We knew from our research people about an orphanage in Pittsburgh that had burned down, and there were no records left of the children raised there That was perfect for me. One of the agents had lived in Pittsburgh, and I had grown up in Pennsylvania.

Being a jewel thief was my idea. There are all kinds of crooks. I needed a specialty that allowed me to work alone and without violence. I couldn’t be a stickup man or a bank robber or hijacker or anything like that. We had an okay from the department to get involved in certain marginal activities, but you had to avoid violence. As a jewel thief, I could say I worked alone. I could come and go as I wanted, and come up with scores that everybody didn’t have to know about because I committed my “crimes” in private.

For a jewel thief and burglar, it was not unusual for a guy to work alone. And since if you pull off the job correctly you don’t confront your victims, there is a minimal chance for violence. That specialty gave me an out whenever anybody would want me to pull a violent job—that’s not my thing.

Given the nature of the operation, there was a likelihood that I would wander into gray areas regarding FBI rules and regulations. But we had to take some chances. We would face things as they came up. How far my role could go, what crimes I could participate in and observe and ignore, how far I could go in having a deal instigated and yet avoid the entrapment issue—such things were part of my preparation before I hit the street.

As a jewel thief, I would have appropriate expertise. I knew enough about alarm systems and surveillance equipment to assess prospective “jobs” that I or others might undertake. A prominent New York City jewelry company gave me a two-week gemology course, knowing only that it was for the FBI and not knowing anything about my operation. I spent time with a gemologist at a New York museum and bought books on precious gems and coins. This didn’t make me a top-flight expert, but at least I knew what to look for.

I had a name, a background, a criminal career. We had to budget the operation. I would need an apartment, car, money to bounce around with, and so on.

We started modestly. For the New York side of Sun Apple, we figured on a six-month operation with a budget of $10,000. That was low, but with a low figure we felt we had a better chance of getting the operation approved. The main thing was getting it launched. Once you’ve got something going and can show some results, it’s easier to extend it. We were confident. Then if we needed another six months, we could go in with an additional proposal.

Nobody dreamed of going for six years and getting where we got to.

We budgeted carefully because the Bureau audits carefully: apartment, phone, leased car, personal expenses, and so on. Our initial figure climbed from $10,000 to $15,000 because we decided to ask to have $5,000 on hand for any special, unexpected expenses, such as if I had to buy into a score.

When all the paperwork was completed, the proposal was sent to headquarters in Washington. They approved it.

Now I had to disappear. Only a handful of people knew about this operation. For their own protection my family knew only that I would be going undercover, not for what. Since the Bureau had no history with deep, long-term undercover operations, we had to make up guidelines as we went along. One of the things we determined was that my true existence as an FBI agent would have to be erased.

In my earlier undercover operation with the heavy-equipment theft ring, everything was treated within the office on a need-to-know basis. Now the security measures would be even more severe. At the New York office of the FBI—then on East Sixty-ninth Street—my desk was cleaned out. My name was erased from office rolls. My personnel file was removed from the office and secretly stashed in the safe of the Special Agent in Charge. Since I was off the office payroll, my paycheck was sent to me outside the normal system. With the exception of those few case agents and contact agents and higher-ups in FBI Headquarters in Washington, nobody in the office or field staffs of the FBI around the country knew what I was doing. If anybody called the office looking for me, they would be told there was nobody employed by the FBI under that name. As far as people inside and outside the Bureau were concerned, nobody by the name of Joseph Pistone had anything to do with the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

We had started thinking about this in April. By the time I was ready to actually hit the street, it was September.

Once I walked out of my FBI office on that September day in 1976, I never returned, never went into any FBI office anywhere, for the next six years that I was undercover.

My coworkers didn’t know what had happened to me. My friends didn’t know. My informants didn’t know. I would utilize no informants in this new Donald Brasco job.

Having disappeared, I proceeded to build my new life. I needed an apartment, a car, a bank account—ordinary things. None of this would be gotten through the Bureau. I would do it on my own, as Donald Brasco, and no strings would be pulled.

I wanted to do everything myself. I didn’t want to go through contacts because I didn’t want anybody to know it was an FBI operation. You never know if somebody’s going to get into somebody else’s files, or if somebody will slip and say something. If nobody knows and nobody’s involved, nobody can slip. And we knew we might be rubbing up against mob guys through the fences we were targeting, and that any slip could be fatal, so everything I did was done by myself, just as Joe Blow off the street.

We created some references for Donald Brasco. We set up a couple of “hello phones,” just numbers people could call to check my references. One was my place of employment. I was a manager of Ace Trucking Company. The other was the building manager at my residence. I was the building manager. The only people who answered those phones were my supervisor or my case agent—or sometimes myself.

I leased a car that fit my role, a yellow 1976 Cadillac Coup de Ville with Florida tags.

Ordinarily I never wear any jewelry, and I don’t care about sharp clothes. For this job I had to dress up a little, some rings and chains and sport clothes. In our budget that was a onetime expense of $750.

I went into a branch of Chase Manhattan Bank in midtown to open a checking account. I filled out the forms. There was a space for prior banking, and I left it blank. The officer looked over my application.

“Where did you do your prior banking?” he asked.

“Why you asking me that?” I said.

“Because we have to verify your signature,” he said.

“I don’t have any prior banking account.”

“Well, that’s what we require for you to open an account.”

It was a quick glimpse into society when you’re not playing by ordinary rules. Here I was, looking presentable in new sport clothes, carrying $1,000 in cash for deposit in a new account, and I couldn’t open an account because I didn’t have any banking history. I wasn’t prepared for that. But I didn’t want to get into any argument, because I was caught off-guard by this guy.

So I said, “Thank you very much,” got up, and left.

There was a branch of Chemical Bank across the street. I decided to try there. But first I thought over what my answer would be if a bank officer there hit me with the same problem.

I walked in and filled out the forms. The guy asked, “Where did you do any prior banking during the last two years?”

“I haven’t done any banking during the last two years,” I said.

“Then I’m afraid we can’t open an account for you,” he said.

“You’re discriminating against me,” I said.

“What do you mean by that?” he said. I wasn’t black or female or any of the other things usually associated with discrimination, and he gave me a strange look. “That’s our rule,” he said, “for everybody.”

I said, “I just got out of jail. I did six years in the can. Now I’m out and trying to be a good citizen. I’ve paid my debt to society, I got a decent job, I want to open up a bank account and be a decent citizen. I’ve got a thousand dollars with me, and all I want is a checking account. And you’re refusing me an account because I haven’t done any banking lately. I’d like to have your name and position here, because I’m gonna go downtown to City Hall and put in a complaint to the civil-rights authorities that I’m being discriminated against.”

Suddenly he looked intimidated—I think more because he was probably sitting across from an ex-con for the first time in his life than because of potential discrimination problems.

He said, “Well, there are some instances where we can make allowances. I think we can help you out.”

So I had a checking account. Now I needed an apartment.

I wasn’t fussy about where or how I lived, except for two things: I didn’t want to be right in the heart of my target areas, and I wanted the apartment to be in a relatively big building—both of these things for the sake of anonymity. I needed a place where I could come and go without attracting attention.

I scoured the papers and looked for a week. Then I found just what I wanted.

I took a one-bedroom apartment—21—G—in Yorkville Towers at Ninety-first Street and Third Avenue, just a few blocks uptown from the most chic blocks of the city’s Upper East Side.

I liked the location and the fact that it had an underground parking garage, and it was not too expensive for what you got—$491.60 per month. It had a big lobby, twenty-four-hour doorman security, and a valet service for deliveries.

I rented furniture for $90.30 per month. I bought sheets, towels, a shower curtain. From my real home I brought in pots and pans and stocked the cupboards.

I told my wife not to call me at the apartment unless it was an emergency. There was a possibility that badguys might be in the apartment when she called, or that my phone might be tapped by badguys. I didn’t tell her that. I told her I would be using the same name as before—Donald Brasco—and that I would call her and get home as often as possible. I didn’t tell her that I might get involved with the Mafia. Maybe I was being selfish, but to me that was the job.

I was ready to hit the street as Don Brasco, jewel thief and burglar.

4

HITTING THE STREET

We had a list of places where wiseguy-type fences were known to hang out. This was going to be a seven-day-a-week job, going around to these bars and restaurants and clubs. The target places were not necessarily “mob” joints. Sometimes they were—night spots and restaurants owned in whole or in part by the mob. More often they were just places where wiseguys and their associates liked to hang out.

I would cruise these places, mostly in midtown or lower Manhattan, have a drink or dinner, not talking much or making any moves, just showing my face so people would get used to seeing me. Places like the Rainbow Room in the RCA Building in Rockefeller Center, Separate Tables on Third Avenue, Vesuvio Restaurant on Forty-eighth Street in the heart of the theater district, Cecil’s Discotheque on Fifty-fourth Street, the Applause Restaurant on Lexington Avenue.

We didn’t concentrate on places in Little Italy because I would have been too obvious. You don’t just start hanging out in places there without knowing anybody. You’re either a tourist or some kind of trouble. I didn’t try to introduce myself to anybody or get into any conversations for a while. Mob guys or fences I recognized were mixed in with ordinary customers, what wiseguys call “citizens,” people not connected with the mob. After I had been to a place a few times, I might say hello to the bartender if he had begun to recognize me. The important thing was just to be seen and not to push anything; just get noticed, get established that I wasn’t just a one-shot visitor.

I didn’t flash around a lot of money because that tags you either as a cop or a mark. A mark is somebody that looks ripe for getting conned out of his money. And a cop typically might flash money when he was looking to make a buy of something illegal, like tempting somebody to offer swag—stolen goods—in order to make a bust. No street guy is going to throw money all over the place unless he’s trying to attract attention. Then the question is: Why is he trying to attract attention? I didn’t want to attract that kind of attention. So to do it right, you don’t go in and start spending a lot of money or showing off stuff or trying to make conversation, because you don’t know them and they don’t know you.

You take a job like this in very small, careful steps—not just to avoid suspicion but also to leave behind you a clean, credible trail. You never know what part of what you do will become part of your history when people want to check on you. You want to establish right away, everywhere you go, that you don’t have a big mouth, and that you don’t have too big a nose about other people’s business. You have to be patient, because you never know where anything will lead. Basically I wanted to keep my own personality, which was low-key. I felt that the time would come in conversation with somebody what my game was.

One of the first places I frequented was Carmello‘s, a pleasant restaurant at 1638 York Avenue, near Eighty-sixth Street and the East River. It wasn’t far from my new apartment, and I wanted a place where I could stop in for a late dinner or drink near where I lived. This wasn’t one of the primary places we had targeted, but we knew that some wiseguy types hung out there. Our information was that the restaurant was owned by Joey and Carmine Zito, who were members of the Genovese crime family, headed by Fat Tony Salerno.

For weeks I roamed around and hung out at these places. Time dragged. I rarely drink alcohol. I don’t smoke. Before I came on the job as an FBI agent, I once had a job as a bartender, and it was one of my least favorite things, hanging out in a bar all night watching people drink and listening to drinkers talk. During these weeks, in the evening at a bar, I might start off with a Scotch, then I’d switch to club soda for the rest of the night.

Occasionally I saw somebody we had targeted. I recognized them from the pictures I had been shown in preparation. But I never got an opportunity to get into conversation with them. It isn’t wise to say to the bartender, “Who is that over there? Isn’t that so-and-so?” I wanted to get to be known as a guy who didn’t ask too many questions, didn’t appear to be too curious. With the guys we were after, it was tough to break in. A wrong move—even if you’re just on the fringes of things—will turn them off. While I was having a couple of drinks or dinner, I was always interested in what was going on in the place. I was always observing, listening, remembering, while still trying to put across the impression that I was oblivious to who was in there.

All through October and November I hung out, watching, listening, not advancing beyond that. It was boring a lot of the time but not discouraging. I knew it would take time. It is a delicate matter, maneuvering your way in. You don’t just step into an operation like this and start dealing. Associates of wiseguys don’t deal with people they don’t know or who somebody else doesn’t vouch for. So for the first two or three months I had to lay the initial groundwork that would lead to being known and having somebody vouch for me.

All this time—in fact, for the entire six years of the overall operation—I never made notes of what I was doing. I didn’t know if at any time I was going to be braced—somebody might check me out, cops or crooks, so I never had anything incriminating in my apartment or on my person. Every couple of days or so, depending on the significance, I would phone my contact agent to fill him on what was going on, who I had seen where, doing what.

One thing that went on at Carmello’s was backgammon. Men played backgammon at the bar. I noticed that a lot of local neighborhood guys would hang out in there, come for dinner, then sit at the bar and play backgammon. And some of the wiseguys that were hanging around would get involved. They played for high stakes—as high as $1,000 a game. That looked like a good way for me to get in, get an introduction, get some conversation going with the regulars. But I didn’t know how to play backgammon. I bought a book and studied up. Another agent whose undercover name was Chuck was a good backgammon player. Chuck had an operation going in the music business. He was a friend of mine. He would come over to my apartment, or I’d go over to his, and he’d teach me backgammon. We played and played, in order for me to get comfortable.

Finally, when I thought I was good enough, I decided to challenge for a game at the bar.

It was near Christmastime, so there was a kind of festive mood in the place, and that seemed like a good time for a newcomer to edge in. On this night there were two boards going at the bar. I watched for a while to see which board had the weaker players. The way you got into the game was to challenge the winner, and that’s the board I challenged the winner on.

The stakes for the first game were $100. That made me nervous because I didn’t have a lot of money to spend. I won that first game, lost the next, and ended up the evening about breaking even.

But the important thing was that it broke the ice. I got introduced around as “Don” for the first time. And now I could sit down and talk to people. We could sit around and talk about the games going on.

After a couple weeks I retreated from the backgammon games. The money was getting a little steep. I played two games for $500 each, lost one then won one. My expense account then was maybe $200 to $300 a week for everything, and I couldn’t go over that without going into an explanation for the accountants at the Bureau. It wasn’t worth it, just to play backgammon with some half-ass wiseguys.

Anyway, by then I had accomplished what I had learned backgammon for. I had gotten to know some people, at least enough to be acknowledged when I came in: “Hey, Don, how’s it going?”

So I wasn’t a strange face any longer. I also got pretty friendly with the bartender, Marty. Marty wasn’t a mob guy, but he was a pretty good knock-around guy who knew what was going on. I got to bullshitting with Marty pretty good near the end of December 1976, and early January of 1977. Conversation rolled around gradually, and he asked me if I lived around there, since I was in there so much. I told him, yeah, I lived up at Ninety-first and Third.

“You from around here?” he asked me.

“I spent some years in this area,” I told him. “Lately I been spending a lot of time in Miami and out in California. I just came in from Miami a couple months ago.”

“What do you do?” he asked me.

That kind of question you don’t answer directly. “Oh, you know, not doing anything right now, you know, hanging out, looking around ...” You bob and weave a little with the guy. I said, “Basically I do anything where I can make a fast buck.”

He had a girlfriend that used to come in at closing, then they’d go out bouncing after work, around the city. A couple times he asked me if I wanted to go, and I backed off, said no thanks. I didn’t want him to think I was anxious to make friends.

Still, I didn’t want him or anybody else in there to think I didn’t have anything going for me. So once in a while I’d bring a female in—somebody that I’d met in another bar across the street from my apartment or something—just for a couple drinks or dinner. And sometimes my agent friend, Chuck, would come in with me for a drink. You can’t go in all the time by yourself, because they think you’re either a fag or a cop. And it’s good to vary your company so they don’t see you with the same people all the time and wonder what’s up. The idea is to blend in, not present yourself in any way at all that makes anybody around you uncomfortable.

Marty’s girlfriend had a girlfriend named Patricia, a good-looking blonde who was going out with one of the wiseguys that hung out there, a bookie named Nicky. A couple times she came in when I was in there and Nicky wasn‘t, and she’d sit down for some small talk with me. At first it was just casual conversation. Then I figured she was coming on to me a little, and I had to be very careful, as an outsider, not to overstep my bounds. The worst thing I could do is appear to be coming on to a wiseguy’s girlfriend, because there are real firm rules against that. If I made that kind of mistake I would have shot my whole couple months of work to get in there.

One night this Patricia asked me if I wanted to have dinner with her. “Nicky’s not gonna be around,” she said. “We could take off and find someplace nice.”

“Thanks,” I said, “but I don’t think so. Not tonight.”

Then I grabbed Marty the bartender off to the side. “Hey, Marty,” I said, “I want you to know that I’m keeping my distance from Patricia because I know that she’s Nicky’s girlfriend. But I don’t want to insult anybody, either.”

Marty said, “I know, I’ve been watching how you handle yourself.”

So I established another small building block in my character: The bartender knew that I knew what the rules were with wiseguys. Most guys who hadn’t been around the streets or around wiseguys might have jumped at an invitation from a girl like that—figuring that, after all, if she makes the play, it must be all right. But with wiseguys there’s a strict code that you don’t mess. I mean, strict.